The Mountain to Climb: Labour's 2020 Challenge Andrew Harrop May 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Leeds Area Management Team First Floor, the Old Library Town Street

West Leeds Area Management Team First Floor, The Old Library Town Street Horsforth Leeds LS18 5BL Pudsey & Swinnow Forum Date: 14 th September 2010 Chair: Councillor Jarosz Present: Nigel Conder (Town Centre Manager), Clare Wiggins (Area Management), Sgt Williamson & PC Sally Johnson (West Yorkshire Police), Jack & Audrey Prince, Suzanne Wainwright / Derek Lawrence (Youth Service), Steve Lightfoot (Pudsey Business Forum), Claire Ducker, Wendy Walton, Mavis Gregory, John Sturdy, C Stevens, R Bennett, Mr & Mrs Rider, E Thomas, M Hirst, KJ & YC Robinson, J & B Knapp, B & G Stephens, V Bergin, L Spurr, S McLennan, D Carver, Carol Barber, Bernadette Gallagher, Greg Wood. 1.0 Welcome & Apologies Action 1.1 Cllr Jarosz welcomed everyone to the meeting. Apologies were received from Barbara Young, Phil Staniforth, Chris Hodgson, Richard Pinder, Graham Walker and David Dufton. 2.0 Minutes & Matters Arising 2.1 The minutes of the last meeting were agreed as an accurate record. 2.2 CW reported that the management committee at Swinnow Community Centre had disbanded in July and the centre was now being managed (probably temporarily) by Leeds City Council. LCC Corporate Property Management had been asked to complete a number of repairs including repairing the lights in the car park. 2.3 CW reported on behalf of PCSO Mick Cox that the potential project at Swinnow Primary School would not now be pursued as the parents needed to use that area for parking. 2.4 In relation to minute 4.5, CW reported that funding for an additional lay- by and parking scheme on the eastern side of Lidget Hill was still being pursued. -

Woodhall View PUDSEY - WEST YORKSHIRE BERKELEY DEVEER

woodhall view PUDSEY - WEST YORKSHIRE BERKELEY DEVEER k HOMES OF DISTINCTION Berkeley DeVeer has many years’ experience in building a diverse range of high-quality homes throughout the UK. Each home we build is carefully designed, combining traditional features with contemporary home comforts, utilising the latest materials and technologies to give you a property that will last. Since our formation, we have gained a reputation for our attention to detail and the careful and painstaking craftsmanship that can elevate a house into a home. From the outset, we have worked hard to make sure our customers can be proud of their homes, placing them at the heart of everything we do. And with a team of experts dedicated to finding new sustainable development land, we plan to continue to bring you homes of distinction for the foreseeable future. CITY LIVING ON YOUR DOORSTEP LIVING with DISTINCTION k Woodhall View is a stunning new development consisting of 52 bespoke luxury homes located in the West Yorkshire market town of Pudsey. Woodhall View is a truly unique development, with contemporary properties located just a stone’s throw away from a plethora of local amenities, ideal to explore the local area whilst offering easy access into Leeds city centre. Carefully designed three, four and five-bedroom homes, Woodhall View has something for everybody, and it’s location means it will appeal to young and old alike, adding a new community to West Leeds. woodhall view THE BLAKE THE JENNER THE WICKHAM PLOTS 1, 3, 25 & 34 PLOTS 43, 44, 48, 49 & 50 PLOTS -

Are Swing Voters Instruments of Democracy Or Farmers of Clientelism? Evidence from Ghana

= = = = = = = = Are Swing Voters Instruments of Democracy or Farmers of Clientelism? Evidence from Ghana Staffan I. Lindberg Keith R. Weghorst = = = = QoG WORKING PAPER SERIES 2010:17= = THE QUALITY OF GOVERNMENT INSTITUTE Department of Political Science University of Gothenburg Box 711 SE 405 30 GÖTEBORG June 2010 ISSN 1653-8919 © 2010 by Staffan I. Lindberg and Keith R. Weghorst. All rights reserved. The authors wishes to acknowledge insightful comments on earlier version from Leonardo Arriola, Dominic Lisanti, Kristin Michelitch, and participants in both the Comparative Politics Colloquium at University of Florida and the Quality of Government workshop at Marstrand 17-19 May, 2010. The survey was carried out in collaboration with research officers at Center for Democratic Development-Ghana and we also wish to recognize the excellent work by the 49 assistants we trained for the field work during summer 2008. The research project was sponsored by the Africa Power and Politics Programme, with funding provided by the UK Department for International Development (DFID). As always, the content, errors, omissions, and flaws of the text is the responsibility of the authors. Are Swing Voters Instruments of Democracy or Farmers of Clientelism? Evidence from Ghana Staffan I. Lindberg Keith R. Weghorst QoG Working Paper Series 2010:17 June 2010 ISSN 1653-8919 Abstract: This paper is one of the first to systematically address the question of whether strength of ethnic identity, political parties’ candidates campaign strategies, poverty, or evaluation of clientelism versus collective/public goods, determines who becomes persuadable voters (swing voters) in new democracies. It brings together three of the major research streams in comparative politics – the literatures on development, democracy, and political clientelism – to properly situate the swing voter as – potentially – the pivotal instrument of democracy and antidote to the public goods deficit in failed developmental states. -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

The Election

Forecast error: what’s happened to the polls since the 2015 UK election? By Timothy Martyn Hill [originally published at significancemagazine.com] When British Prime Minister Theresa May called a snap election for 8 June 2017, it seemed like a smart move politically. Her Conservative Party was riding high in the opinion polls, with a YouGov poll in the Times giving them 44%, a lead of 21 points over her nearest rivals, the Labour Party[0514a]. Were an election to be held the next day (as surveys often suppose[0514b]) May looked to be on course for a convincing win and an increased majority in the House of Commons. But then came the obvious question: “Can we actually trust the polls?” The media seemed sceptical. Though they had not shied away from reporting poll results in the months since the 2015 general election, they were clearly still sore about the errors made last time, when survey results mostly indicated the country was heading for a hung parliament. So, can we trust the polls this time around? It’s not possible to say until we have election results to compare them to. But what we can do is consider the work that’s been done to try to fix whatever went wrong in 2015. There’s a lot to cover, so I’ve broken the story up by key dates and periods: • The election – 7 May 2015 • The reaction – 8-10 May • The suspects • Early speculation – 11 May-18 June • The Sturgis inquiry meets – 19 June • The investigation focuses – 20 June-31 December • Unrepresentative samples indicted – 1 January-30 March 2016 • The Sturgis inquiry report – 31 March • A heated debate – 1 April-22 June • EU referendum and reaction – 23 June-19 July • US presidential election and reaction – 20 July-31 December • The calm before the storm – 8 December 2016-18 April 2017 • Have the polls been fixed? The election – 7 May 2015 The night before the 2015 General Election, the atmosphere was tense but calm. -

14A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

14A bus time schedule & line map 14A Bramley - Pudsey Owlcotes View In Website Mode The 14A bus line (Bramley - Pudsey Owlcotes) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bramley <-> Pudsey: 10:15 AM - 12:15 PM (2) Pudsey <-> Bramley: 10:55 AM - 12:55 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 14A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 14A bus arriving. Direction: Bramley <-> Pudsey 14A bus Time Schedule 24 stops Bramley <-> Pudsey Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 10:15 AM - 12:15 PM Bus Station Stand D, Bramley Stocks Hill, Leeds Tuesday 10:15 AM - 12:15 PM Aston Road, Bramley Wednesday 10:15 AM - 12:15 PM Rosseƒeld Approach, Bramley Thursday 10:15 AM - 12:15 PM 435 Stanningley Road, Leeds Friday 10:15 AM - 12:15 PM Railsƒeld Mount, Bramley Saturday Not Operational Elder Mount, Leeds Station Mount, Bramley Station Avenue, Leeds 14A bus Info Fairƒeld Mount, Bramley Direction: Bramley <-> Pudsey Stops: 24 Fairƒeld Avenue, Bramley Trip Duration: 32 min Line Summary: Bus Station Stand D, Bramley, Aston Swinnow Lane Stanningley Rd, Bramley Road, Bramley, Rosseƒeld Approach, Bramley, Stanningley Field Close, Leeds Railsƒeld Mount, Bramley, Station Mount, Bramley, Fairƒeld Mount, Bramley, Fairƒeld Avenue, Bramley, Swinnow Lane Rycroft Ave, Swinnow Swinnow Lane Stanningley Rd, Bramley, Swinnow Swinnow Lane, Leeds Lane Rycroft Ave, Swinnow, Swinnow Co-Op, Swinnow, Harley Road, Swinnow, Intake Road, Swinnow Co-Op, Swinnow Pudsey, Kent Road Sycamore Chase, Pudsey, Kent Road Acres -

Conclusion: an Election That Satisfied Few and Solved Little

This is a repository copy of Conclusion: An Election that Satisfied Few and Solved Little. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/137841/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Tonge, J, Leston-Bandeira, C orcid.org/0000-0002-6131-4607 and Wilks-Heeg, S (2018) Conclusion: An Election that Satisfied Few and Solved Little. Parliamentary Affairs, 71 (suppl_1). pp. 267-276. ISSN 0031-2290 https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsx069 © The Author 2018. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Hansard Society; all rights reserved. This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Parliamentary Affairs following peer review. The version of record is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsx069 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Conclusion: An Election that Satisfied Few and Solved Little Jonathan Tonge, Cristina Leston-Bandeira and Stuart Wilks-Heeg Rarely can a partial election victory have felt so akin to a defeat for a party. -

Easter-Holidays-2015-1-1.Pdf

STOCKELD PARK—March 28th—April 19th Design your own chocolate flavour, Easter adventure, Easter crafts, Easter maze mystery, giant egg hunt & spring time face painting EASTER HOLIDAYS ARMLEY MILLS 31st March –17th April Friday 3rd April -17th April Easter bunny hunt & craft activities 10:00am—5:00pm LOTHERTON HALL 2nd-19th April Easter egg trail 10:00am –4:00 pm 4th & 18th April Easter bunny, outdoor and hopping games 1:00pm-3:00pm 8th April Mad Hatters dress up day 11:00am-3:00pm 2nd-19th April Spring time festival- new trails, garden games & nest box making 11:00am -4:00pm 15th April Easter time workshop 1:00am-3:00pm Swinnow Primary School KIRKSTALL ABBEY Swinnow Rd, 3rd April—9th April Bunny Scarecrow train 10:00 am– 3:00 pm Free Leeds, 11th April—19th April Bunny Scarecrow train 10:00 am—3:00 pm Free LS13 4PG ABBEY HOUSE MUSEUM 0113 3783090 3rd April –6th April Bunny fun 10:00 am—12:00 & 2:00 pm—4:00 pm TEMPLE NEWSAM 3rd April–5th April Easter egg hunt 10:30 am Great time to visit the new born animals 3rd April—6th April Decorate an egg character 11:00 am –12:30 pm & 2:00pm 3:30pm PUDSEY PARK 16 April 10—3pm Make your own bunny crafts and Easter egg trail. Free PLEASE NOTE NORMAL ADMISSION APPLIES TO ALL ACTIVITES UNLESS IT STATES OTHERWISE APRIL HOLIDAYS Friday 3rd April- Friday 19th April LIMITED PLACES AVAILABLE ON ALL ACTIVITIES BOOK QUICKLY TO SECURE YOUR PLACES!!! Easter Activities at Swinnow COST Easter Activities at Swinnow COST MON Baby Group—for babies under 1 years old 6th Bank Holiday Closed MON 13th £1 per family 1:30-2:30 Messy Play– 10am-11:30am children under 8yrs Children’s Centre open as normal TUE come and get messy and enjoy some Easter activi- £1 per family TUES 14th Please look at the other activities offered across 7th ties the city see back of leaflet for more details. -

In a West Yorkshire Constituency, 1920S – 1970S

LIBERAL ROOTS: ThE LIBEral ParTY IN A WEST YORKShirE CONSTITUENCY, 1920S – 1970s From 1966 to 1971, as a teenager, Jaime Reynolds lived in Morley, West Yorkshire, now part of south Leeds. During that time he was an active member of the Liberals, who were enjoying something of a renaissance in the Batley & Morley constituency. In 1969 Batley borough council was briefly the only local authority in England and Wales where the Liberals were the largest party. Jaime’s desire was to chart the story of Liberal fortunes in these Yorkshire mill towns and pay tribute to the efforts of the pioneers who led the revival there. Thanks to the Liberal Democrat History Group, a few years ago he reestablished contact with Peter Wrigley. 26 Journal of Liberal History 80 Autumn 2013 LIBERAL ROOTS: ThE LIBEral ParTY IN A WEST YORKShirE CONSTITUENCY, 1920S – 1970s eter was one of those pio- in Morley in 1852. He moved away the prosperity and civic spirit it neers, parliamentary candi- as a child and though he was said to enjoyed at the end of the nine- Pdate in 1970 and February have few sentimental attachments teenth century. 1974 and still today an active Lib- to his birthplace, he returned in Morley and Batley, and neigh- eral Democrat in the Batley & Spen 1895 to open the town hall and in bouring Dewsbury, were at the constituency. Peter’s recollections, 1913 to be invested as a freeman of centre of the ‘shoddy trade’ – the local research, and the memories he the borough. He was treated as a recycling of woollen rags to make has gathered from others involved local hero. -

81 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

81 bus time schedule & line map 81 Leeds - Pudsey View In Website Mode The 81 bus line (Leeds - Pudsey) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Leeds City Centre <-> Pudsey: 7:20 AM - 5:40 PM (2) Pudsey <-> Leeds City Centre: 6:22 AM - 5:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 81 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 81 bus arriving. Direction: Leeds City Centre <-> Pudsey 81 bus Time Schedule 61 stops Leeds City Centre <-> Pudsey Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:20 AM - 5:40 PM City Square B, Leeds City Centre 10 Inƒrmary Street, Leeds Tuesday 7:20 AM - 5:40 PM Wellington C, Leeds City Centre Wednesday 7:20 AM - 5:40 PM Wellington E, Leeds City Centre Thursday 7:20 AM - 5:40 PM Cropper Gate, Leeds Friday 7:20 AM - 5:40 PM Kirkstall Fire Stn, Burley Saturday 7:20 AM - 5:40 PM Washington Street, Woodhouse Itv Yorkshire, Hyde Park 81 bus Info Viaduct Road Burley Place, Hyde Park Direction: Leeds City Centre <-> Pudsey Burley Place, Leeds Stops: 61 Trip Duration: 50 min Canal Rd Forge Lane, Armley Line Summary: City Square B, Leeds City Centre, Canal Road, Leeds Wellington C, Leeds City Centre, Wellington E, Leeds City Centre, Kirkstall Fire Stn, Burley, Washington Canal Road Pickering St, Armley Street, Woodhouse, Itv Yorkshire, Hyde Park, Viaduct Road Burley Place, Hyde Park, Canal Rd Forge Lane, Crab Lane, Armley Armley, Canal Road Pickering St, Armley, Crab Lane, Crab Lane, Leeds Armley, Armley Town Street, Armley, Carr Crofts Leisure Centre, Armley, Carr Crofts -

210A, Dick Lane, Tyersal Bd4

210A, DICK LANE, TYERSAL BD4 8JH £375 PCM Duplex Apartment Two Double Bedrooms Open Plan Living Area Modern Kitchen Area Modern Bathroom Suite Neutral Décor Double Glazing and Central Heating Unfurnished Available Now Bond £500 210A, DICK LANE, TYERSAL BD4 8JH £375 PCM GENERAL DESCRIPTION A two double bedroom duplex apartment situated in the area of Tyersal. Will be of particular interest to professionals seeking well-presented and stylish accommodation which benefits from: white uPVC double glazing; open plan living area with modern fitted kitchen area; off street parking; modern bathroom suite with mains shower; gas central heating with combination boiler; neutral décor; laminate flooring. Briefly comprises: inner hall; open plan living kitchen including two seat breakfast bar and bar stools; bathroom; staircase and landing; two double bedrooms (one with built-in wardrobes). Offers good commuting access to both Leeds and Bradford and an early inspection is recommended to appreciate the style and size of the accommodation on offer. Sorry, no smokers. Sorry, no pets. Available now. Unfurnished. Bond £500. ROOM MEASUREMENTS INNER HALL 4' 6" x 2' 11" (1.37m x 0.89m) OPEN PLAN LIVING KITCHEN 15' 11" x 14' 4" (4.85m x 4.37m) max BATHROOM 10' 3" x 4' 11" (3.12m x 1.5m) STAIRCASE AND LANDING 5' 6" x 3' 7" (1.68m x 1.09m) DOUBLE BEDROOM ONE 13' 0" x 10' 10" (3.96m x 3.3m) max into eves DOUBLE BEDROOM TWO 15' 8" x 8' 2" (4.78m x 2.49m) max into robes ADMINISTRATION FEES Homebuyers Property Services charge ONLY £80.00 per adult when applying for a property to let. -

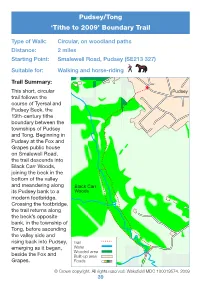

Tithe Boundary Walk – Pudsey / Tong

Pudsey/Tong ‘Tithe to 2009’ Boundary Trail Type of Walk: Circular, on woodland paths Distance: 2 miles Starting Point: Smalewell Road, Pudsey (SE213 327) Suitable for: Walking and horse-riding Trail Summary: This short, circular Pudsey trail follows the course of Tyersal and Pudsey Beck, the 19th-century tithe boundary between the townships of Pudsey and Tong. Beginning in Pudsey at the Fox and Grapes public house on Smalewell Road, the trail descends into Black Carr Woods, joining the beck in the bottom of the valley and meandering along Black Carr its Pudsey bank to a Woods modern footbridge. Crossing the footbridge, the trail returns along the beck’s opposite bank, in the township of Tong, before ascending the valley side and rising back into Pudsey, Trail emerging as it began, Water Wooded area beside the Fox and Built-up area Grapes. Roads © Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Wakefi eld MDC 100019574. 2009 39 Directions: Go around the left-hand side of the Fox and Grapes public house on Smalewell Road. Of the buildings you see here today, none was standing at the time of the Pudsey tithe map’s creation in 1847. On the site of the public house was tithe plot number 196, which was an allotment belonging to John Parker, and leased to John Sugden. Proceeding between the black and white metal gate posts to your left, onto a steeply sloping track, you begin your journey along a route frequented since at least the Victorian era. This track appears on the Pudsey tithe map as a wide vehicular access road leading from plot 197a, at the top of the hill on your left, down into Black Carr Woods.