Sundt, Wilbur OH127

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Managed Instruction in Navy Training. INSTITUTION Naval Training Equipment Center, Orlando, Fla

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 089 780 IR 000 505 AUTHOR Middleton, Morris G.; And Others TITLE Computer Managed Instruction in Navy Training. INSTITUTION Naval Training Equipment Center, Orlando, Fla. Training Analysis and Evaluation Group. REPORT NO NAVTRADQUIPCEN-TAEG-14 PUB DATE Mar 74 NOTE 107p. ERRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$5.40 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Computer Assisted Instruction; Computers; Cost Effectiveness; Costs; *Educational Programs; *Feasibility Studies; Individualized Instruction; *Management; *Military Training; Pacing; Programing Languages; State of the Art Reviews IDENTIFIERS CMI; *Computer Managed Instruction; Minicomputers; Shipboard Computers; United States Navy ABSTRACT An investigation was made of the feasibility of computer-managed instruction (CMI) for the Navy. Possibilities were examined regarding a centralized computer system for all Navy training, minicomputers for remote classes, and shipboard computers for on-board training. The general state of the art and feasibility of CMI were reviewed, alternative computer languages and terminals studied, and criteria developed for selecting courses for CMI. Literature reviews, site visits, and a questionnaire survey were conducted. Results indicated that despite its high costs, CMI was necessary if a significant number of the more than 4000 Navy training courses were to become individualized and self-paced. It was concluded that the cost of implementing a large-scale centralized computer system for all training courses was prohibitive, but that the use of minicomputers for particular courses and for small, remote classes was feasible. It was also concluded that the use of shipboard computers for training was both desirable and technically feasible, but that this would require the acquisition of additional minicomputers for educational purposes since the existing shipboard equipment was both expensive to convert and already heavily used for other purposes. -

The Foreign Service Journal, April 2010

C1-C4_FSJ_0410_COV:proof 3/16/10 5:40 PM Page C1 DNA TESTING FOR IMMIGRANT VISAS? ■ THE MEANING OF COURAGE $3.50 / APRIL 2010 OREIGN ERVICE FJ O U R N A L STHE MAGAZINE FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS PROFESSIONALS HANDS ACROSS THE SEA The Foreign Service Helps in Haiti C1-C4_FSJ_0410_COV:proof 3/16/10 5:40 PM Page C2 01-16_FSJ_0410_FRO:first 3/19/10 4:18 PM Page 3 OREIGN ERVICE FJ O U R N A L S CONTENTS April 2010 Volume 87, No. 4 F OCUS ON The Foreign Service Role in Haiti A COMPASSIONATE AND COMPETENT RESPONSE / 17 The work USAID and State have done in Haiti following the Jan. 12 earthquake shows why they should take the lead in disaster response. By J. Brian Atwood RELIEF EFFORTS RESONATE IN WEST AFRICA / 21 Naval personnel from three West African nations took part in the Cover and inside illustration relief effort as part of a U.S.-African military program. by Ben Fishman By Benjamin East PRESIDENT’S VIEWS / 5 Two Important Blueprints for ECHOES OF GRACE / 24 Labor-Management Collaboration The local staff who form the backbone of Embassy Port-au-Prince By Susan R. Johnson saw their society literally disintegrate in seconds. By Michael Henning SPEAKING OUT / 14 DNA: The Future of ‘THE EXPERIENCE OF A LIFETIME’ / 27 Immigrant Visa Processing Embassy Santo Domingo has played a special role By Simon Hankinson in the disaster relief efforts in neighboring Haiti. REFLECTIONS / 72 By Team Santo Domingo Courage By Elisabeth Merton TALES FROM THE FIELD / 33 Hundreds of AFSA members from around the world are responding to the crisis in Haiti. -

Ladies and Gentlemen

reaching the limits of their search area, ENS Reid and his navigator, ENS Swan decided to push their search a little farther. When he spotted small specks in the distance, he promptly radioed Midway: “Sighted main body. Bearing 262 distance 700.” PBYs could carry a crew of eight or nine and were powered by two Pratt & Whitney R-1830-92 radial air-cooled engines at 1,200 horsepower each. The aircraft was 104 feet wide wing tip to wing tip and 63 feet 10 inches long from nose to tail. Catalinas were patrol planes that were used to spot enemy submarines, ships, and planes, escorted convoys, served as patrol bombers and occasionally made air and sea rescues. Many PBYs were manufactured in San Diego, but Reid’s aircraft was built in Canada. “Strawberry 5” was found in dilapidated condition at an airport in South Africa, but was lovingly restored over a period of six years. It was actually flown back to San Diego halfway across the planet – no small task for a 70-year old aircraft with a top speed of 120 miles per hour. The plane had to meet FAA regulations and was inspected by an FAA official before it could fly into US airspace. Crew of the Strawberry 5 – National Archives Cover Artwork for the Program NOTES FROM THE ARTIST Unlike the action in the Atlantic where German submarines routinely targeted merchant convoys, the Japanese never targeted shipping in the Pacific. The Cover Artwork for the Veterans' Biographies American convoy system in the Pacific was used primarily during invasions where hundreds of merchant marine ships shuttled men, food, guns, This PBY Catalina (VPB-44) was flown by ENS Jack Reid with his ammunition, and other supplies across the Pacific. -

Cannon News 0314

CANNON NEWSCANNON March 2014 NEWS Page 1 Francis Cannon VFW Post 7589 Manassas, Virginia March 2014 February 23: 8th District Commander Rick Raskin observes as Peter MacLeod, District 8 Youth Chair, presents an award to Peter Nosal, winner of the District 8 Patriot’s Pen contest for 2013/14. Peter is a 6th grade student at Auburn Middle School and was submitted through Post 9835, Warrenton. In This Issue: COLA Penalty Removed for Most VFW Statement on Military Retiree COLA Vote Benefits Fights Not Over GMU to offer course on Vietnam this summer Celebrity Soldiers Upcoming Events New VFW Store website CANNON NEWS—2013 Clair B. Poff Public Relations Award for Most Outstanding Post Publication/Newsletter, VFW Department of Virginia CANNON NEWS March 2014 Page 2 From the Editor Have you visited your Post website They are available to view online . lately? www.vfw7589.org Take a look... Its the best place to keep current with what’s going on at your Post. We Please contact me if you have any- update it at least once a week, and thing you’d like posted or have any often more frequently. comments or suggestions. Recent additions include 14 new Rick Raskin episodes of “Operation Freedom” the [email protected] monthly veteran interview show broadcast on Comcast Cable and hosted by our own Steve Botello. Commander’s Report Most are not veterans and have never if warranted and not eliminated be- experienced the long period of sepa- cause another social program; not to ration from family and friends. The have their retirement entitlements long nights awake on an outpost, eroded; and most importantly, not listening, thinking you hear some- just being ignored. -

The Alliance of Military Reunions

The Alliance of Military Reunions Louis "Skip" Sander, Executive Director [email protected] – www.amr1.org – (412) 367-1376 153 Mayer Drive, Pittsburgh PA 15237 Directory of Military Reunions How to Use This List... Members are listed alphabetically within their service branch. To jump to a service branch, just click its name below. To visit a group's web site, just click its name. Groups with names in gray do not currently have a public web site. If you want to contact one of the latter, just send us an email. To learn more about a member's ship or unit, click the • to the left of its name. Air Force Army Coast Guard Marine Corps Navy Other AIR FORCE, including WWII USAAF ● 1st Computation Tech Squadron ● 3rd Air Rescue Squadron, Det. 1, Korea 1951-52 ● 6th Weather Squadron (Mobile) ● 7th Fighter Command Association WWII ● 8th Air Force Historical Society ● 9th Physiological Support Squadron ● 10th Security Police Association ● 11th Bombardment Group Association (H) ● 11th & 12th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadrons Joint Reunion ● 13 Jungle Air Force Veterans Association ● 15th Radio Squadron Mobile (RSM) USAFSS ● 20th Fighter Wing Association ● 34th Bomb Squadron ● 34th Tactical Fighter Squadron, Korat Thailand ● 39th Fighter Squadron Association ● 47th Bomb Wing Association ● 48th Communications Squadron Association ● 51st Munitions Maintenance Squadron Association ● 55th & 58th Weather Reconnaissance Squadrons ● 57th TCS/MAS/AS/WPS (Troop Carrier Squadron, Military Airlift Squadron, Airlift Squadron, Weapons Squadron) Military -

Americanlegionvo1356amer.Pdf (9.111Mb)

Executive Dres WINTER SLACKS -|Q95* i JK_ J-^ pair GOOD LOOKING ... and WARM ! Shovel your driveway on a bitter cold morning, then drive straight to the office! Haband's impeccably tailored dress slacks do it all thanks to these great features: • The same permanent press gabardine polyester as our regular Dress Slacks. • 1 00% preshrunk cotton flannel lining throughout. Stitched in to stay put! • Two button-thru security back pockets! • Razor sharp crease and hemmed bottoms! • Extra comfortable gentlemen's full cut! • 1 00% home machine wash & dry easy care! Feel TOASTY WARM and COMFORTABLE! A quality Haband import Order today! Flannel 1 i 95* 1( 2 for 39.50 3 for .59.00 I 194 for 78. .50 I Haband 100 Fairview Ave. Prospect Park, NJ 07530 Send REGULAR WAISTS 30 32 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 pairs •BIG MEN'S ADD $2.50 per pair for 46 48 50 52 54 INSEAMS S( 27-28 M( 29-30) L( 31-32) XL( 33-34) of pants ) I enclose WHAT WHAT HOW 7A9.0FL SIZE? INSEAM7 MANY? c GREY purchase price D BLACK plus $2.95 E BROWN postage and J SLATE handling. Check Enclosed a VISA CARD# Name Mail Address Apt. #_ City State .Zip_ 00% Satisfaction Guaranteed or Full Refund of Purchase $ § 3 Price at Any Time! The Magazine for a Strong America Vol. 135, No. 6 December 1993 ARTICLE s VA CAN'T SURVIVE BY STANDING STILL National Commander Thiesen tells Congress that VA will have to compete under the President's health-care plan. -

Appendix As Too Inclusive

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Appendix I A Chronological List of Cases Involving the Landing of United States Forces to Protect the Lives and Property of Nationals Abroad Prior to World War II* This Appendix contains a chronological list of pre-World War II cases in which the United States landed troops in foreign countries to pro- tect the lives and property of its nationals.1 Inclusion of a case does not nec- essarily imply that the exercise of forcible self-help was motivated solely, or even primarily, out of concern for US nationals.2 In many instances there is room for disagreement as to what motive predominated, but in all cases in- cluded herein the US forces involved afforded some measure of protection to US nationals or their property. The cases are listed according to the date of the first use of US forces. A case is included only where there was an actual physical landing to protect nationals who were the subject of, or were threatened by, immediate or po- tential danger. Thus, for example, cases involving the landing of troops to punish past transgressions, or for the ostensible purpose of protecting na- tionals at some remote time in the future, have been omitted. While an ef- fort to isolate individual fact situations has been made, there are a good number of situations involving multiple landings closely related in time or context which, for the sake of convenience, have been treated herein as sin- gle episodes. The list of cases is based primarily upon the sources cited following this paragraph. -

Major Fire Drill Exercise Page 8

Major Fire Drill Exercise Ship’s Force firefighters battle a simulated class alpha fire aboard USS Gunston Hall (LSD 44) during a major fire drill April 29. The drill tested emergency response Page 8 readiness of personnel, procedures and equipment from Gunston Hall, City of Norfolk Fire and Emergency Services and Marine Hydraulic International shipyard. (U.S. Navy Photo by Damage Controlman 3rd Class Hannah Sweet/Released) The Maintainer • Mid-Atlantic Regional Maintenance Center • Volume 10 | Issue 5 | May 2019 Featured Stories The Maintainer is the official Mid-Atlantic Regional Maintenance Center publication. All comments of this publication do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Department of the Navy. This is a monthly newsletter and the deadline for submission of articles is the fifth of each month. Correspondence should be directed to Public Affairs, Code 1100P, Building LF-18 or email: [email protected]. Gold Disk Award Winner ET2 Dustin Powell - Powell repaired nearly 60 CCAs during the first quarter of Fiscal Year (FY) 2019, and he recently received notice that his work during the second quarter of FY19 has earned him 6 an additional award. MARMC Leads Completion of Monterey SRA - MARMC provided oversight for the Chief of Naval Operations availability, which was contracted to Marine Hydraulics International (MHI) in Norfolk, Virginia, in September 2018, with a work package that included tank work; extensive structural repairs; Consolidated 10 Afloat Network and Enterprise Services (CANES) modifications; intake repairs and more items. Production Department’s Outside Machine Shop: Jack of All Trades - With so many jobs coming and going from the Outside Machine Shop, one might ask – what exactly do the Sailors and civilians in the shop specialize in? If you ask the shop’s Leading Petty Officer and 2019 Senior Sailor of the 2nd Quarter, Machinist 16 Mate 1st Class Stephanie Faenza, she will tell you they do a little bit of everything. -

Norfolk's Nauticus: USS Wisconsin BB‐64

Norfolk’s Nauticus: USS Wisconsin BB‐64 The history of the U.S. Navy’s use of battleships is quite interesting. Some say the first battleship was the USS Monitor, used against the CSS Virginia (Monitor) in Hampton Roads in 1862. Others say it was the USS Michigan, commissioned in 1844. It was the first iron‐ hulled warship for the defense of Lake Erie. In any case, battleships, or as some have nicknamed them “Rolling Thunder,” have made the United States the ruler of the high seas for over one century. A history of those famous ships can be found in the source using the term bbhistory. By the way, BB‐64 stands for the category battleship and the number assigned. This photo program deals with the USS Wisconsin, which is moored in Norfolk and part of the Hampton Road Naval Museum and Nauticus. Though the ship has been decommissioned, it can be recalled into duty, if necessary. On July 6, 1939, the US Congress authorized the construction of the USS Wisconsin. It was built at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Its keel was laid in 1941, launched in 1943 and commissioned on April 15, 1944. The USS Wisconsin displaces 52,000 tons at full load, length 880 fee, beam 108 feet and draft at 36 feet. The artillery includes 16‐inch guns that fire shells weighing one‐ton apiece. Other weapons include antiaircraft guns and later added on missile launchers. The ship can reach a speed of 30 nautical miles (knots) per hour or 34 miles mph. The USS Wisconsin’s first battle star came at Leyte Operation, Luzon attacks in the Pacific in December 1944. -

2. Location Street a Number Not for Pubhcaoon City, Town Baltimore Vicinity of Ststs Maryland Coot 24 County Independent City Cods 510 3

B-4112 War 1n the Pacific Ship Study Federal Agency Nomination United States Department of the Interior National Park Servica cor NM MM amy National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form dato««t«««d See instructions in How to CompMe National Raglatar Forma Type all entries—complsts applicable sections 1. Name m«toMc USS Torsk (SS-423) and or common 2. Location street a number not for pubHcaOon city, town Baltimore vicinity of ststs Maryland coot 24 county Independent City cods 510 3. Classification __ Category Ownership Status Present Use district ±> public _X occupied agriculture _X_ museum bulldlng(s) private unoccupied commercial park structure both work In progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious JL_ object in process X_ yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted Industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Baltimore Maritime Museum street * number Pier IV Pratt Street city,town Baltimore —vicinltyof state Marvlanrf 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Department of the Navy street * number Naval Sea Systems Command, city, town Washington state pc 20362 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title None has this property been determined eligible? yes no date federal state county local depository for survey records ctty, town . state B-4112 Warships Associated with World War II In the Pacific National Historic Landmark Theme Study" This theme study has been prepared for the Congress and the National Park System Advisory.Board in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Public Law 95-348, August 18, 1978. The purpose of the theme study is to evaluate sur- ~, viving World War II warships that saw action in the Pacific against Japan and '-• to provide a basis for recommending certain of them for designation as National Historic Landmarks. -

Winter 2013 Full Issue the .SU

Naval War College Review Volume 65 Article 19 Number 1 Winter 2012 Winter 2013 Full Issue The .SU . Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation War College, The .SU . Naval (2012) "Winter 2013 Full Issue," Naval War College Review: Vol. 65 : No. 1 , Article 19. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol65/iss1/19 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. War College: Winter 2013 Full Issue NAVAL WAR C OLLEGE REVIEW NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REVIEW Winter 2012 Volume 65, Number 1 Winter 2012 Winter Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2012 1 NWC_Winter2012.indd 1 9/22/2011 9:17:07 AM Naval War College Review, Vol. 65 [2012], No. 1, Art. 19 Cover Orbis terrae compendiosa descriptio, a double-hemisphere projection fi rst pub- lished in 1569 by the Flemish cartogra- pher Gerhardus Mercator (1512–94), fa- mous for the eponymous global projection widely used today for, especially, nautical charts. This version was engraved by his son Rumold (1545–99) and issued in 1587. The map is one of thirty rare maps of similarly high technical and aesthetic value exhibited in Envisioning the World: The Earliest Printed Maps, 1472 to 1700. The exhibit, organized by the Sonoma County Museum in Santa Rosa, California, is drawn from the collection of Henry and Holly Wendt. -

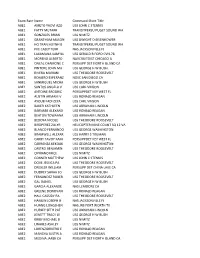

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE1 FATTY MUTARR TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 GONZALES BRIAN USS NIMITZ ABE1 GRANTHAM MASON USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER ABE1 HO TRAN HUYNH B TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 IVIE CASEY TERR NAS JACKSONVILLE FL ABE1 LAXAMANA KAMYLL USS GERALD R FORD CVN-78 ABE1 MORENO ALBERTO NAVCRUITDIST CHICAGO IL ABE1 ONEAL CHAMONE C PERSUPP DET NORTH ISLAND CA ABE1 PINTORE JOHN MA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 RIVERA MARIANI USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE1 ROMERO ESPERANZ NOSC SAN DIEGO CA ABE1 SANMIGUEL MICHA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 SANTOS ANGELA V USS CARL VINSON ABE2 ANTOINE BRODRIC PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 AUSTIN ARMANI V USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 AYOUB FADI ZEYA USS CARL VINSON ABE2 BAKER KATHLEEN USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BARNABE ALEXAND USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 BEATON TOWAANA USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BEDOYA NICOLE USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 BIRDPEREZ ZULYR HELICOPTER MINE COUNT SQ 12 VA ABE2 BLANCO FERNANDO USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 BRAMWELL ALEXAR USS HARRY S TRUMAN ABE2 CARBY TAVOY KAM PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 CARRANZA KEKOAK USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 CASTRO BENJAMIN USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 CIPRIANO IRICE USS NIMITZ ABE2 CONNER MATTHEW USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE2 DOVE JESSICA PA USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 DREXLER WILLIAM PERSUPP DET CHINA LAKE CA ABE2 DUDREY SARAH JO USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 FERNANDEZ ROBER USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 GAL DANIEL USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 GARCIA ALEXANDE NAS LEMOORE CA ABE2 GREENE DONOVAN USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 HALL CASSIDY RA USS THEODORE