14.4 Phags-Pa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 14.4, Phags-Pa

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati . & Dr. K. Muniratnam Director i/c, Epigraphy, ASI, Mysore. Dr. Rajat Sanyal Dept. of Archaeology, University of Calcutta. Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. 1 Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Indian Epigraphy Module Name/Title Evolution of North Indian Scripts from Brahmi Module Id IC / IEP / 12 Notion of early writing in India; The nature of early scripts; Pre requisites Reasons behind evolution of scripts Development from Early to Middle Brahmi; Regionalization and other Developments in Late Brahmi; Objectives Characteristics of Late Brahmi; Genesis of Proto-Regional Script; Siddhamatrka and its chronological varieties Early Brahmi; Regionalization; Middle Brahmi; Late Keywords Brahmi; Proto-Regional scripts; Siddhamatrka; Nagari; Gaudi E-text (Quadrant-I) : 1. Introduction According to D.C Sircar, the Brahmi script and the Prakrit language are the two salient features of Maurya inscriptions found outside the uttarapatha division of ancient Bharatavarsa (Kumaridvipa). The Brahmi script is read from left to right. According to earlty Indian literary traditions, Brahma, the brahmanical god of creation, is usually believed to be the creator of the speech and, thus, the script also. Scholars are of different opinions regarding the origin of Brahmi. According to some scholars, Brahmi is an indigenous script that developed in India. Others believe that it is an Indian modification of a foreign system of writing exactly like Kharosthi, the exact path which is still difficult to trace. Sircar suggests that the development of the Brahmi script can be assumed to be the result of an attempt to write the Middle Indo-Aryan languages in the alien script of the prehistoric peoples of India. -

14 South and Central Asia-III 14 Ancient Scripts

The Unicode® Standard Version 12.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2019 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 12.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-22-1 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode12.0.0/) 1. -

General Historical and Analytical / Writing Systems: Recent Script

9 Writing systems Edited by Elena Bashir 9,1. Introduction By Elena Bashir The relations between spoken language and the visual symbols (graphemes) used to represent it are complex. Orthographies can be thought of as situated on a con- tinuum from “deep” — systems in which there is not a one-to-one correspondence between the sounds of the language and its graphemes — to “shallow” — systems in which the relationship between sounds and graphemes is regular and trans- parent (see Roberts & Joyce 2012 for a recent discussion). In orthographies for Indo-Aryan and Iranian languages based on the Arabic script and writing system, the retention of historical spellings for words of Arabic or Persian origin increases the orthographic depth of these systems. Decisions on how to write a language always carry historical, cultural, and political meaning. Debates about orthography usually focus on such issues rather than on linguistic analysis; this can be seen in Pakistan, for example, in discussions regarding orthography for Kalasha, Wakhi, or Balti, and in Afghanistan regarding Wakhi or Pashai. Questions of orthography are intertwined with language ideology, language planning activities, and goals like literacy or standardization. Woolard 1998, Brandt 2014, and Sebba 2007 are valuable treatments of such issues. In Section 9.2, Stefan Baums discusses the historical development and general characteristics of the (non Perso-Arabic) writing systems used for South Asian languages, and his Section 9.3 deals with recent research on alphasyllabic writing systems, script-related literacy and language-learning studies, representation of South Asian languages in Unicode, and recent debates about the Indus Valley inscriptions. -

Download Kindle # the Bhaiksuki Manuscript of The

1VH0121VXCPD < PDF // The Bhaiksuki Manuscript of the Candralamkara: Study, Script Tables, and Facsimile Edition... Th e Bh aiksuki Manuscript of th e Candralamkara: Study, Script Tables, and Facsimile Edition (Hardback) Filesize: 3.79 MB Reviews The ebook is great and fantastic. We have read and i also am sure that i am going to likely to go through once again again down the road. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Erica Turcotte) DISCLAIMER | DMCA MDVMLVEW1JSJ # PDF ^ The Bhaiksuki Manuscript of the Candralamkara: Study, Script Tables, and Facsimile Edition... THE BHAIKSUKI MANUSCRIPT OF THE CANDRALAMKARA: STUDY, SCRIPT TABLES, AND FACSIMILE EDITION (HARDBACK) The Department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies, United States, 2010. Hardback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book. This volume discusses the Bhaiksuki manuscript of the Candralamkara ( Ornament of the Moon ), a commentary of the twelh century based on the Candravyakarana, Candragomin s seminal Buddhist grammar of Sanskrit (fih century). The discovery of the Bhaiksuki script and of all available written sources are described. The detailed study of this codex unicus of the Candralamkara is accompanied by a facsimile edition and extensive tables of the script, a long-felt desideratum in the field of palaeography. The Buddhist author of the commentary has been identified for the first time, and the nature of his treatise and its position in the Candra school of grammar have been expounded. The history of the manuscript and newly discovered traces of the Bhaiksuki script in Tibet are discussed. This publication will serve as a prolegomenon necessary for the preparation of a critical edition of the Candralamkara, which until now was believed to have been lost irretrievably. -

Iso/Iec Jtc 1/Sc 2/Wg 2 N4605-A

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N4605-A DATE: 2014-10-02 Tentative Agenda – Meeting # 63 Topic (Document No.) Proposed Outcome 1. Opening and roll call (N4551) Update Distribution List 2. Approval of the agenda (N4605-A) Approved agenda 3. Approval of minutes of meeting 62 (N4553) Approved Minutes 4. Review action items from previous meeting (N4553-AI) Updated Action Item List 5. JTC1 and ITTF matters FYI 5.1 Results of Voting: ISO/IEC FDIS 10646 4th ed (N4586) Published 2014-09-01 – SC2 N4358/WG2 N4618 6. SC2 matters: 6.1. SC2 Notification of approval of subdivision of work (N4578) FYI 6.2. Notification of SC2 approval of SC2 N4319, request from FYI the Unicode Consortium for changing the category of liaison from C to A (N4577 ) 6.3. Summary of Voting on 10646: DAM1 (Ed 4) Review and progress (N4611, N4611-BSI) 6.4. Proposed Disposition of Ballot Comments DAM1 (N4615) Approve and progress 7. WG2 matters 7.1 Possible ad hoc meetings – Nushu (N4647 ad hoc report) (8:30 Wed), Tangut (post close on Monday) Consider (Tangut - N4642) 7.2 Summary of Voting on 10646 4th edition PDAM2 (N4614) FYI (N4614 Commentfiles PDAM2) 7.3 Proposed Disposition of Ballot Comments on PDAM2 Approve and progress 10646 4th ed (N4616) 7.4 Roadmap Snapshot (N4617) Adoption 8. IRG status and reports 8.1 IRG No. 42 Resolutions – Qindao, China (N4582) FYI 8.2 IRG No. 42 Summary Report (N4581) Adoption 8.3 IRG Principles and Procedures version 7.5 (N4579) FYI 8.4 Report of Inaccurate Source Reference for Twelve FYI HKSCS Compatibility characters(N4598) 9. -

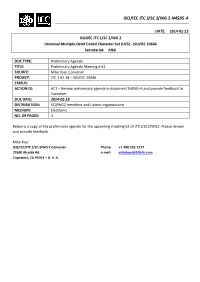

Preliminary Agenda

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N4505-A DATE: 2014-02-23 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) - ISO/IEC 10646 Secretariat: ANSI DOC TYPE: Preliminary Agenda TITLE: Preliminary Agenda Meeting # 62 SOURCE: Mike Ksar, Convener PROJECT: JTC 1.02.18 – ISO/IEC 10646 STATUS: ACTION ID: ACT – Review preliminary agenda in document N4505-A and provide feedback to Convener DUE DATE: 2014-02-18 DISTRIBUTION: SC2/WG2 members and Liaison organizations MEDIUM: Electronic NO. OF PAGES: 4 Below is a copy of the preliminary agenda for the upcoming meeting 62 of JTC1/SC2/WG2. Please review and provide feedback. Mike Ksar ISO/IEC/JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Convener Phone: +1 408 255-1217 22680 Alcalde Rd. e-mail: [email protected] Cupertino, CA 95014 – U. S. A. ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N4505-A DATE: 2014-02-23 Preliminary Agenda – Meeting # 62 Topic (Document No.) Proposed Outcome 1. Opening and roll call (N4401) Update Distribution List 2. Approval of the agenda (N4505-A) Approved agenda 3. Approval of minutes of meeting 61 (N4403) Approved Minutes 4. Review action items from previous meeting (N4403-AI) Updated Action Item List 5. JTC1 and ITTF matters 6. SC2 matters: 6.1. SC2 Program of Work FYI 6.2. FDAM2 Results of 3rd edition – 100% approved (N4532) FYI 6.3. Results of PDAM1 subdivision proposal (N4531) FYI 6.4. Summary of Voting DIS – 4th edition (N4524 & N4524-A) Consider and progress 6.5. Draft additional Repertoire DIS – 4th edition (N4459) Consider and Progress 6.6. -

N4469 Proposal to Encode the Bhaiksuki Script in ISO

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4469 L2/13-167 2013-07-22 Proposal to Encode the Bhaiksuki Script in ISO/IEC 10646 Anshuman Pandey Dragomir Dimitrov Department of History Fachgebiet Indologie und Tibetologie University of Michigan Philipps-Universität Marburg Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A. Marburg, Germany [email protected] [email protected] July 22, 2013 1 Introduction This is proposal to encode the Bhaiksuki script in the Universal Character Set (ISO/IEC 10646). It replaces “Preliminary Proposal to Encode the Bhaiksuki Script in ISO/IEC 10646” (N4121 L2/11-259). 2 Background Bhaiksuki ( bhaikṣukī; Devanagari भैुक) is a Brahmi-based script that was used around the turn of the first millenium mainly in the present-day states of Bihar and West Bengal in India, as well as in regions that are now part of Bangladesh. Records have been also located in Tibet, Nepal, and Burma. The script is known variously as the ‘Arrow-Headed Script’ or ‘Point-Headed Script’ in English, ‘Pfeilspitzenschrift’ in German, and ‘Śaramātr̥ kā Lipi’ in Hindi and modern Sanskrit. An older designation, ‘Sindhura’, has been used in Tibet for at least three centuries. The script is attested exclusively in Buddhist textual materials. Only eleven inscriptions and four manuscripts written in this script are presently known to exist. These are the Bhaiksuki manuscripts of the Abhidhar- masamuccayakārikā, Maṇicūḍajātaka, Candrālaṃkāra, and at least one more Buddhist canonical text. The codex of the Abhidharmasamuccayakārikā was once kept in Tibet, but it is now inaccessible and its exact place of preservation is unknown. The fourth codex was discovered in Tibet and was recently shown in a Chinese documentary; however, information about this manuscript is limited. -

Overview and Rationale

Integration Panel: Maximal Starting Repertoire — MSR-5 Overview and Rationale REVISION – APRIL 06, 2021 – PUBLIC COMMENT Table of Contents 1 Overview 3 2 Maximal Starting Repertoire (MSR-5) 3 2.1 Files 3 2.1.1 Overview 3 2.1.2 Normative Definition 4 2.1.3 HTML Presentation 4 2.1.4 Code Charts 4 2.2 Determining the Contents of the MSR 5 2.3 Process of Deciding the MSR 6 3 Scripts 8 3.1 Comprehensiveness and Staging 8 3.2 What Defines a Related Script? 9 3.3 Separable Scripts 9 3.4 Deferred Scripts 9 3.5 Historical and Obsolete Scripts 9 3.6 Selecting Scripts and Code Points for the MSR 10 3.7 Scripts Appropriate for Use in Identifiers 10 3.8 Modern Use Scripts 11 3.8.1 Common and Inherited 12 3.8.2 Scripts included in MSR-1 12 3.8.3 Scripts added in MSR-2 12 3.8.4 Scripts added in MSR-3 through MSR-5 13 3.8.5 Modern Scripts Ineligible for the Root Zone 13 3.9 Scripts for Possible Future MSRs 13 3.10 Scripts Identified in UAX#31 as Not Suitable for identifiers 14 4 Exclusions of Individual Code Points or Ranges 16 4.1 Historic and Phonetic Extensions to Modern Scripts 16 4.2 Code Points That Pose Special Risks 17 4.3 Code Points with Strong Justification to Exclude 17 4.4 Code Points That May or May Not be Excludable from the Root Zone LGR 17 4.5 Non-spacing Combining Marks 18 Integration Panel: Maximal Starting Repertoire — MSR-3 Overview and Rationale 5 Discussion of Particular Code Points 20 5.1 Digits and Hyphen 20 5.2 CONTEXT O Code Points 21 5.3 CONTEXT J Code Points 21 5.4 Code Points Restricted for Identifiers 21 5.5 Compatibility -

Unicode Reference Lists: Other Script Sources

Other Script Sources File last updated October 2020 General ALA-LC Romanization Tables: Transliteration Schemes for Non-Roman Scripts, Approved by the Library of Congress and the American Library Association. Tables compiled and edited by Randall K. Barry. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1997. ISBN 0-8444-0940-5. Adlam Barry, Ibrahima Ishagha. 2006. Hè’lma wallifandè fin èkkitago’l bèbèrè Pular: Guide pra- tique pour apprendre l’alphabet Pulaar. Conakry, 2006. Ahom Barua, Bimala Kanta, and N.N. Deodhari Phukan. Ahom Lexicons, Based on Original Tai Manuscripts. Guwahati: Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies, 1964. Hazarika, Nagen, ed. Lik Tai K hwam Tai (Tai letters and Tai words). Souvenir of the 8th Annual conference of Ban Ok Pup Lik Mioung Tai. Eastern Tai Literary Association, 1990. Kar, Babul. Tai Ahom Alphabet Book. Sepon, Assam: Tai Literature Associate, 2005. Alchemical Symbols Berthelot, Marcelin. Collection des anciens alchimistes grecs. 3 vols. Paris: G. Steinheil, 1888. Berthelot, Marcelin. La chimie au moyen âge. 3 vols. Osnabrück: O. Zeller, 1967. Lüdy-Tenger, Fritz. Alchemistische und chemische Zeichen. Würzburg: JAL-reprint, 1973. Schneider, Wolfgang. Lexikon alchemistisch-pharmazeutischer Symbole. Weinheim/Berg- str.: Verlag Chemie, 1962. Anatolian Hieroglyphs Hawkins, John David, and Halet Çambel. Corpus of Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions. Ber- lin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2000. ISBN 3-11-010864-X. Herbordt, Suzanne. Die Prinzen- und Beamtensiegel der hethitischen Grossreichszeit auf Tonbullen aus dem Ni!antepe-Archiv in Hattusa. Mit Kommentaren zu den Siegelin- schriften und Hieroglyphen von J. David Hawkins. Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 2005. ISBN: 3-8053-3311-0. -

N4573: Final Proposal to Encode the Bhaiksuki

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4573 L2/14-091 2014-04-23 Final Proposal to Encode the Bhaiksuki Script in ISO/IEC 10646 Anshuman Pandey Dragomir Dimitrov Department of History Fachgebiet Indologie und Tibetologie University of Michigan Philipps-Universität Marburg Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A. Marburg, Germany [email protected] [email protected] April 23, 2014 1 Introduction This is a proposal to encode the Bhaiksuki script in the Universal Character Set (ISO/IEC 10646). It replaces the following documents: • N4121 L2/11-259 “Preliminary Proposal to Encode the Bhaiksuki Script in ISO/IEC 10646” • N4469 L2/13-167 “Proposal to Encode the Bhaiksuki Script in ISO/IEC 10646” • N4489 L2/13-194 “Revised Proposal to Encode the Bhaiksuki Script in ISO/IEC 10646” • L2/14-036 “Revised Proposal to Encode the Bhaiksuki Script in ISO/IEC 10646” This document is a revision of L2/14-036. Major changes include revision of the glyphs for certain vowel signs, the addition of two digits, and a second gap filler. Other changes include additional information on contextual forms of vowel signs and consonant letters, as well as digits. 2 Background Bhaiksuki ( bhaikṣukī; Devanagari भैुक) is a Brahmi-based script that was used around the turn of the first millenium mainly in the present-day states of Bihar and West Bengal in India, as well as in regions that are now part of Bangladesh. Records have been also located in Tibet, Nepal, and Burma. The script is known variously as the ‘Arrow-Headed Script’ or ‘Point-Headed Script’ in English, ‘Pfeilspitzenschrift’ in German, and ‘Śaramātr̥ kā Lipi’ in Hindi and modern Sanskrit. -

Expanding the Unicode Repertoire: Un-Encoded Scripts of Africa and Asia

Expanding the Unicode Repertoire Unencoded Scripts of Africa and Asia Deborah Anderson, SEI, Department of Linguistics, UC Berkeley Anshuman Pandey, Department of History, University of Michigan IUC 38 • November 5, 2014 Already Encoded Scripts (12) “Modern” use (8) Bamum/Bamum Supplement Historic use (3) Bassa Vah Egyptian Hieroglyphs Ethiopic/Ethiopic Supplement and Meroitic Cursive Extensions Meroitic Hieroglyphs Mende Kikakui Liturgical use (1) N’Ko Coptic Osmanya Note: Scripts in bold italic had assistance from Tifiangh SEI Vai Bassa Vah (Unicode 7.0) Scripts of Africa Unencoded scripts (historical) – possible candidates for encoding Additions to Egyptian Hieroglyphs (Ptolemaic) – over 7K characters Hieratic? Demotic? Source: Chicago Demotic Dictionary Numidian? Unencoded scripts (modern or near- modern) – good candidates (13) Adlam * (1978) Mwangwego (1979) Bagam (1910) Nwagu Aneke Igbo (1960s) Beria (1980s) Oberi Okaime (1927) Bete (1956) Borama (Gadabuursi) (1933) Garay (Wolof) (1961) * Approved by UTC Hausa Raina Kama (1990s) Kaddare (1952) Kpelle (1930s) Loma (1930s) Mandombe (1978) Unencoded scripts – not currently good candidates for encoding (21) Aka Umuagbara Igbo (1993) Masaba (1930) Aladura Holy alphabet (1927) Ndebe Igbo (2009) Bassa (1836) New Nubian (2005) Esan oracle rainbow (1996) Nubian Kenzi (1993) Fula (2 scripts) (1958/1963) Oromo (1956) Hausa (2 scripts) (1970/1998) Soni (2001) Kii (2006) Wolof Saalliw wi (2002) Kru alphabet (1972) Yoruba FaYe (2007) Luo (2 scripts)