The Challenge of Building an Independent Citizenship Regime in a Partially Recognised State: the Case of Kosovo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VISA POLICIES in SOUTH EASTERN EUROPE EWI Policy Brief

November 2006 VISA POLICIES IN SOUTH EASTERN EUROPE EWI Policy Brief VISA POLICIES IN SOUTH EASTERN EUROPE: A HINDRANCE OR A STEPPING STONE TO EUROPEAN INTEGRATION? By Martin Baldwin-Edwards Edited by Lejla Haveric and Marina Peunova i MISSION Founded in 1980, the EastWest Institute works to promote solutions that reduce threats to peace and security. International and action-oriented, EWI is nonpartisan and independent. WHAT WE DO • We bring together leaders from government, business, military, media and other sectors of society in confi dential and public dialogue to tackle intractable problems, build trust, reconcile disparate views and reframe issues. • We address dangerous fault lines between the emerging East and the West. We serve as an institution of choice for state and non-state actors who seek to cooperate, prevent confl ict and manage global challenges. • We identify, help develop and support emerging leaders as we build a global community committed to confl ict prevention and security. www.ewi.info About the Author Martin Baldwin-Edwards is co-director of the Mediterranean Migration Observatory, Panteion University, Athens, Greece. He contributed to the regional study for the Global Commission on International Migration on Th e Middle East and the Mediterranean, has served as a consultant on immigration to two European governments, and is the author of more than fi ft y publications on international migration, including Th e Politics of Immigration in Western Europe (ed. with M Schain, 1994) and Immigrants and the Informal Economy in Southern Europe (ed. with J Arango, 1999). About the EastWest Institute’s Work in South Eastern Europe The EastWest Institute has over a decade of experience working in South Eastern Europe and currently operates a number of cross-border cooperation projects aimed at promoting stability across the region. -

After the Red Passport: Towards an Anthropology of the Everyday Geopolitics of Entrapment in the EU’S ‘Immediate Outside’

After the red passport: towards an anthropology of the everyday geopolitics of entrapment in the EU’s ‘immediate outside’ Stef Jansen Manchester University Suggesting building bricks for an anthropology of everyday geopolitics, this text analyses affective engagements with regulation, here of cross-border mobility. Following the logic of the regulation that constitutes them, I conceptualize zones of humiliating entrapment through documentary requirements – experienced by citizens of Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia – as the EU’s shrinking ‘immediate outside’. Using ethnography, I embed bodily experiences in visa queues in people’s engagements with changing Eurocentric spatiotemporal rankings, refracting this entrapment against the privileges of certain foreigners (such as me) and against their own remembered mobility with the ‘red’ Yugoslav passport. I propose that complementing the dominant focus on the role of (national) identity politics in geopolitical affect with one on regulation and ranking is a central task for a critical anthropology of everyday geopolitics in peripheries. In 2008, some friends and I were having a beer in Sarajevo when an acquaintance of theirs joined our table. He asked me what had brought me to Sarajevo and I gave him my well-worn, one-minute reply. He then asked me:‘So you chose to be here?’ Rising to the bait of his irony I replied that, yes, I had been lucky enough to develop my research project myself and that I enjoyed being there, adding in jest: ‘Nikomenetjeradaprovodimvrijemeovdje’ [‘Nobody is forcing me to spend time here’]. At that moment my friend intervened without blinking an eyelid:‘Da je tako, bio bi Bosanac!’ [‘If that were the case (i.e. -

Foreign Nationals

Foreign Nationals In most cases, you will need a residence permit that allows self-employment before you can en- ter into an independent contractor agreement or fee agreement. Provided your residence permit allows gainful employment (“Erwerbstätigkeit gestattet”), any gainful work is allowed and you do not need any further permission. If you have a residence permit for another reason, you must request a change to the condi- tions. If you do not have a residence permit, you must apply for one (fees apply). Before you perform any work or provide any services contact the Hamburg Welcome Center: http://welcome.hamburg.de. You can arrange an appointment via email: [email protected] (Current waiting period for an appointment: up to 3 months.) Alternatively, contact your local district office—check here for your nearest office: www.hamburg.de/behoerden- finder/hamburg/11254942 Generally, you will need to present the following documents to be issued with a residence per- mit: passport or national identification card biometric photograph current certificate of residence proof of sufficient health insurance coverage Note: If you do not have statutory health insurance, you must provide proof that you have private health insurance. completed and signed registration form administration fees additional documents as necessary See here for more information and forms (also in other languages): http://welcome.hamburg.de/formulare If you have any questions, contact the member of the Strategic Purchasing department responsi- ble for independent contractor agreements and fee agreements (732): www.uni-ham- burg.de/uhh/organisation/praesidialverwaltung/finanz-und-rechnungswesen/einkauf/strate- gischer-einkauf/werkvertraege.html See the following pages for more information on the different employment groups / countries of origin. -

Geografski Institut „Jovan Cvijić”, SANU (Str.142)

GEOGRAPHICAL INSTITUTE “JOVAN CVIJIC” SASA JOURNAL OF THE … Vol. 59 № 2 YEAR 2009 911.37(497.11) SETLLEMENTS OF UNDEVELOPED AREAS OF SERBIA Branka Tošić*1, Vesna Lukić**, Marija Ćirković** *Faculty of Geography of the University in Belgrade **Geographical Institute “Jovan Cvijic” SASA, Belgrade Abstract: Analytical part of the paper comprises the basic demo–economic, urban–geographic and functional indicators of the state of development, as well as changes in the process of development in the settlements and their centres on undeveloped area of Serbia in the period in which they most appeared. The comparison is made on the basis of complex and modified indicators2, as of undeveloped local territorial units mutually, so with the republic average. The basic aims were presented in the final part of the paper, as well as the strategic measures for the development of settlements on these areas, with a suggestion of activating and valorisation of their spatial potentials. The main directions are defined through the strategic regional documents of Serbia and through regional policy of the European Union. Key words: population, activities, development, settlements, undeveloped areas, Serbia. Introduction The typology and categorisation of municipalities/territorial units with a status of the city, given in the Strategy of the Regional Development of the Republic of Serbia for the period from 2007 to 2012 (Official Register, no. 21/07) served as the basis for analysis and estimation of the settlements in undeveloped areas on the territory of the Republic of Serbia. In that document, 37 municipalities/cities were categorized as underdeveloped (economically undeveloped or demographically endangered municipalities). -

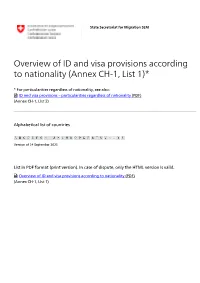

Overview of ID and Visa Provisions According to Nationality (Annex CH-1, List 1)*

State Secretariat for Migration SEM Overview of ID and visa provisions according to nationality (Annex CH-1, List 1)* * For particularities regardless of nationality, see also: ID and visa provisions – particularities regardless of nationality (PDF) (Annex CH-1, List 2) Alphabetical list of countries Version of 14 September 2021 List in PDF format (print version). In case of dispute, only the HTML version is valid. Overview of ID and visa provisions according to nationality (PDF) (Annex CH-1, List 1) A Country National passports and Visa required for stays Visa required for stays (Countries in italics: not other travel documents of up to 90 daysB) of more than 90 daysC) recognized by Switzerland) authorizing entry into Switzerland Afghanistan see A) Yes V Yes Albania see A) No V12 Yes F: D M: D Algeria see A) Yes V Yes F: D, S M: D, S Andorra see A) No No Angola see A) Yes V Yes F: D, S M: D, S Antigua and Barbuda see A) No V1 Yes Argentina see A) No V1 Yes Armenia see A) Yes V Yes F: D M: D Australia see A) No V1 Yes Austria P5 No No (Schengen) ID Azerbaijan see A) Yes V Yes M: D, S* B Country National passports and Visa required for stays Visa required for stays (Countries in italics: not other travel documents of up to 90 daysB) of more than 90 daysC) recognized by Switzerland) authorizing entry into Switzerland Bahamas see A) No V1 Yes Bahrain see A) Yes V Yes Bangladesh see A) Yes V Yes Barbados see A) No V1 Yes Belarus see A) Yes V Yes Belgium P5 No No (Schengen) ID SB BEL-1 Belize see A) Yes V Yes Benin see A) Yes V Yes F: D, -

Final Evaluation Report.Pdf

Fall 08 FINAL EVALUATION Serbia Thematic window Conflict Prevention & Peace Building Programme Title: Promoting Peace Building in Southern Serbia May Prepared by: 2013 A consortium of evaluators under supervision of TARA IC d.o.o, Novi Sad Prologue This final evaluation report has been coordinated by the MDG Achievement Fund joint programme in an effort to assess results at the completion point of the programme. As stipulated in the monitoring and evaluation strategy of the Fund, all 130 programmes, in 8 thematic windows, are required to commission and finance an independent final evaluation, in addition to the programme’s mid-term evaluation. Each final evaluation has been commissioned by the UN Resident Coordinator’s Office (RCO) in the respective programme country. The MDG-F Secretariat has provided guidance and quality assurance to the country team in the evaluation process, including through the review of the TORs and the evaluation reports. All final evaluations are expected to be conducted in line with the OECD Development Assistant Committee (DAC) Evaluation Network “Quality Standards for Development Evaluation”, and the United Nations Evaluation Group (UNEG) “Standards for Evaluation in the UN System”. Final evaluations are summative in nature and seek to measure to what extent the joint programme has fully implemented its activities, delivered outputs and attained outcomes. They also generate substantive evidence-based knowledge on each of the MDG-F thematic windows by identifying best practices and lessons learned to be carried forward to other development interventions and policy-making at local, national, and global levels. We thank the UN Resident Coordinator and their respective coordination office, as well as the joint programme team for their efforts in undertaking this final evaluation. -

Requirments to Travel in Croatia

REQUIRMENTS TO TRAVEL IN CROATIA SCHENGEN COUNTRIES: AUSTRIA FINLAND ICELAND LUXEMBOURG PORTUGAL SWITZERLAND BELGIUM FRANCE ITALY MALTA SLOVAKIA CZECH GERMANY LATVIA NETHERLANDS SLOVENIA REPUBLIC DENMARK GREECE LEICHTENSTEIN NORWAY SPAIN ESTONIA HUNGARY LITHUANIA POLAND SWEDEN NATIONALITIES REQUIRING VISA TO ENTER CROATIA: A D J N ST. TOME AND PRINCIPE AFGHANISTAN DJIBOUTI JAMAICA NAMIBIA SUDAN ALBANIA DOMINICAN JORDAN NAURU SURINAME REPUBLIC ALGERIA NEPAL T ANGOLA E K NIGER TAIWAN ARMENIA ECUADOR KAZAKHSTAN NIGERIA TAJIKISTAN AZERBAIJAN EGYPT KENYA NORTH KOREA TANZANIA EQUATORIAL KOSOVO THAILAND GUINEA B ERITREA KUWAIT O TOGO BAHRAIN KYRGYZSTAN OMAN TUNIS BANGLADESH F TURKEY BELARUS FIJI L P TURKMENISTAN BELIZE LAOS PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY BENIN G LEBANON PAPUA NEW U GUINEA BHUTAN GABON LESOTHO PHILIPPINES UGANDA BOLIVIA GAMBIA UKRAINE BOSNIA AND GEORGIA M Q UZBEKISTAN HERZEGOVINA BOTSWANA GHANA MACEDONIA QUATAR BURKINA FASO GUINEA MADAGASCAR V BURUNDI GUINEA BISSAU MALAWI R VIETNAM C GUYANA MALDIVES RUSSIA CAMBODIA MALI RWANDA Y CAMEROON H MAURITANIA YEMEN CAPE VERDE HAITI MOLDOVA S CENTRAL AFRICAN MONGOLIA SAUDI ARABIA Z REPUBLIC CHAD I MONTENEGRO SENEGAL ZAMBIA CHINA INDIA MOROCCO SERBIA ZIMBABWE COMOROS INDONESIA MOZAMBIQUE SIERRA LEONE CONGO IRAN MYANMAR/ BURMA SOMALIA 1 COTE D'IVOR IRAQ SOUTH AFRICA CUBA SRI LANKA VISA FOR CROATIA: Please note it is very important that the visa is multiple or double entry. If it is a single entry, a passenger cannot travel to Venice on a day trip, because the passenger will not have a permission to re-enter Croatia in the evening. IMPORTANT: Passengers who require a visa for Croatia can use either of the following, instead of a Croatian visa: Schengen residence permit- issued by one of the Schengen area member states. -

Author's Original Manuscript

SUBMITTED VERSION Aleksandar Petrović & ĐorĐe Stefanović Kosovo, 1944-1981: The rise and the fall of a communist 'nested homeland' Europe-Asia Studies, 2010; 62(7):1073-1106 © 2010 University of Glasgow This is an original manuscript / preprint of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Europe-Asia Studies, on 09 Aug 2010 available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2010.497016 PERMISSIONS http://authorservices.taylorandfrancis.com/sharing-your-work/ Author’s Original Manuscript (AOM)/Preprint The AOM is your original manuscript (sometimes called a “preprint”) before you submitted it to a journal for peer review. You can share this version as much as you like, including via social media, on a scholarly collaboration network, your own personal website, or on a preprint server intended for non-commercial use (for example arXiv, bioRxiv, SocArXiv, etc.). Posting on a preprint server is not considered to be duplicate publication and this will not jeopardize consideration for publication in a Taylor & Francis or Routledge journal. If you do decide to post your AOM anywhere, we ask that, upon acceptance, you acknowledge that the article has been accepted for publication as follows: “This article has been accepted for publication in [JOURNAL TITLE], published by Taylor & Francis.” After publication please update your AOM / preprint, adding the following text to encourage others to read and cite the final published version of your article (the “Version of Record”): “This is an original manuscript / preprint of an article published by Taylor & Francis in [JOURNAL TITLE] on [date of publication], available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/[Article DOI].” 7 May 2020 http://hdl.handle.net/2440/124583 Kosovo, 1944 - 1981: The Rise and the Fall of a Communist ‘Nested Homeland’ Aleksandar Petrović and Đorđe Stefanović 1 Abstract Based on established explanations of unintended effects of Communist ethno-federalism, the nested homeland thesis seeks to explain the failure of Kosovo autonomy to satisfy either Albanian or Serbian aspirations. -

Milena Kojić MODEL of the REGIONAL STATE in EUROPE

University of Belgrade University La Sapienza, Rome University of Sarajevo Master Program State Management and Humanitarian Affairs Milena Kojić MODEL OF THE REGIONAL STATE IN EUROPE - A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS WITH FOCUS ON THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Master Thesis Belgrade, August 2010 University of Belgrade University La Sapienza, Rome University of Sarajevo Master Program State Management and Humanitarian Affairs Milena Kojić MODEL OF THE REGIONAL STATE IN EUROPE - A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS WITH FOCUS ON THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Master Thesis Members of the Commission: Assoc. Prof. dr. Zoran Krstić, Mentor Prof. Emer. dr. Marija Bogdanović, President Prof. dr. Dragan Simić, Member Defense date: __________________ Mark: __________________ Belgrade, August 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………......…1 PART I 1. Key terms and basic theoretical categories .....................................................................4 2. Basic models of state organization .................................................................................7 a) Consociational state .............................................................................................7 b) Unitary state – simple state ................................................................................10 c) Federation – complex state ……………………………………........................11 d) Regional state – tertium genus ………………………………...........................14 PART II 1. Republic of Italy……………………............................................................................18 -

List of Countries for Which a Visa Is Necessary

ATTACHMENT I to the Reg. CE 539/2001: COUNTRIES FOR WHOM A VISA IS NECESSARY Afghanistan Ghana Russia Algeria Guinea Rwanda Angola Guinea-Bissau São Tomé and Príncipe Saudi Arabia Guyana Senegal Armenia Haiti Sierra Leone Azerbaijan India Somalia Bahrein Indonesia South Africa Bangladesh Iran South Sudan Belarus Iraq Sri Lanka Belize Ivory Coast/Côte d'Ivoire Sudan Benin Jamaica Suriname Bhutan Jordan Swaziland Burma/Myanmar Kazakhstan Syria Bolivia Kenya Tajikistan Botswana Kuwait Thailand Burkina Faso Kyrgyzstan Tanzania Burundi Laos Togo Cambodia Lebanon Tunisia Cameroon Lesotho Turkey Cape Verde Liberia Turkmenistan Central African Republic Libya Ukraine Chad Madagascar Uganda China Malawi Uzbekistan Comoros Maldives Vietnam Congo Mali Yemen Cuba Mauritania Zambia Democratic Republic of Mongolia Zimbabwe Congo Morocco Djibouti Mozambique Dominican Republic Namibia NB: The citizens of some Ecuador Nepal countries not present on Egypt Niger this list are exempt from Eritrea Nigeria the requirement of a visa Equatorial Guinea North Korea only under certain Ethiopia Oman circumstances. Please, Fiji Pakistan therefore, also read the Gabon Papua New Guinea second part of this Gambia Philippines document. Georgia Qatar For an on-line verification: http://vistoperitalia.esteri.it/home.aspx ATTACHMENT II to the Reg. CE 539/2001 EXEMPTION FROM THE REQUIREMENT OF A VISA 1. Countries exempt from the requirement of a visa Albania (exemption only for those with biometric passports) Andorra Antigua and Barbuda (the exemption accord will be signed -

List 1: Overview of ID and Visa Provisions According to Nationality (Version of 25 May 2010)

Federal Department of Justice and Police FDJP Federal Office of Migration FOM Entry, Stay and Return Directorate Entry and Admission Department List 1: Overview of ID and visa provisions according to nationality (version of 25 May 2010) Country National passports♦ and other Visa required for Visa required for (Countries in italics: not recog- travel documents authorizing en- stays of up to 3 stays of more than 3 nized by Switzerland) try into Switzerland months months Afghanistan B, ST YesV Yes Albania SB YesV, V7 YesV7 Algeria SB YesV, V2 YesV2 Andorra No No Angola SB YesV Yes Antigua and Barbuda SB NoV1 Yes Argentina SB, K NoV1 Yes Armenia YesV, V7 YesV7 Australia NoV1 Yes Austria (Schengen) P5, ID No No Azerbaijan YesV Yes Bahamas NoV1 Yes Bahrain YesV Yes Bangladesh YesV Yes Barbados SB NoV1 Yes Belarus SB YesV Yes Belgium (Schengen) P5, ID, SB, 1 No No Belize YesV Yes Benin YesV Yes Bhutan YesV Yes Bolivia YesV, V5 Yes Bosnia and Herzegowina YesV, V2 Yes B “Business Passport” ID Identity card K Consular passport P5 Passport expired for less than five years SB Seaman’s book ST Student passport 1 French or Luxembourg identity cards for foreign nationals (these ID cards must prove that the holder has Belgian citizenship); children’s ID for under 15-year olds, for children less than 12 years old travelling accompanied by their parents (also valid without photo); tempo- rary Belgian identity card. V Third state members in possession of both a valid permanent residence permit issued by a Schengen member state (cf. -

65 Chapter 5 Compilation of Digital Spatial Data Sets and Information

Chapter 5 Compilation of Digital Spatial Data Sets and Information Disclosure 5.1 Current State and Evaluation of GIS Database at MEM 5.1.1 Prehistory of Database Creation at MEM The Department of Mining & Geology (DMG) has implemented a GIS-based government solution in order to provide a positive administrative environment that will support increased mining and development activity in Serbia through several projects (Table 5.1). In 2001, a text-based mineral resource database was created with GIS datasets through a project supported by the BRGM. Table 5.1 Development of a GIS Database at MEM-DMG Project name Organization Year 1 CISGEM: Computerized Information System for Geological Exploration & Mining MEM 2001 2 Database of Central & South-Eastern Europe BRGM 2001 3 Formation of a GIS-based database of mineral occurrences in Serbia MEM 2001-02 4 GIS Software Application and Training UNDP 2002-03 5 Digital Spatial Data for Serbia MEM 2004-05 6 CISGEM project extension MEM 2006-07 7 JICA M/P Study JICA 2007-08 5.1.2 BRGM’s Databases of the Mineral Deposits and Mining Districts of Serbia The BRGM’s databases for mineral deposits and mining districts of Serbia was constructed in 2001. Information on the mineral deposits and mining districts of Serbia is compiled with the collaboration of the Faculty of Mines and Geology of the University of Belgrade and the Geological Institute. The databases comprised information on mineral deposits and districts, which is stored in text-based databases (Table 5.2). The BRGM has also compiled GIS-based mineral resource maps with the scale of 1:750,000, and energy minerals, base and precious metallic minerals, and industrial minerals, as well as the main mining districts, are plotted on topographic and simplified geology maps.