Gender, Tragedy, and the American Dream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nathaniel Hawthorne's the Scarlet Letter: Hester Prynne's Counter

1 Universidad de Chile Facultad de Filosofía y Humanidades Departamento de Lingüística Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter: Hester Prynne’s counter cultural feminism. Alumna Rayen Vielma Antivil Profesor patrocinante Francisco De Undurraga Santiago de Chile 2019 2 Agradecimientos Ante todo, quisiera agradecer a Catalina, sin quien no podría haber escrito esta tesis, ni luchado a través de mis últimos años dentro de la carrera. Gracias por la fuerza constante. Quisiera agradecer a mi papá por sus consejos, y a mi mamá por la paciencia. Gracias por no rendirse conmigo a lo largo de los años. Por último, me gustaría agradecer a mi mejor amiga, Tiare, por enseñarme que la fortaleza es tan eterna como uno se proponga que sea; y a mi hermano menor, Aarón, quien siempre ha sido mi motor. 3 Index Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Theoretical framework ................................................................................................................ 9 Hester Prynne: a counter cultural feminist ................................................................................. 19 Rejection of Hester: otherness and taboo ................................................................................... 27 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................ 33 Bibliography ............................................................................................................................ -

I Pledge Allegiance to the Embroidered Scarlet

I PLEDGE ALLEGIANCE TO THE EMBROIDERED SCARLET LETTER AND THE BARBARIC WHITE LEG ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University Dominguez Hills ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Humanities ____________ by Laura J. Ford Spring 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the people who encouraged and assisted me as I worked towards completing my master’s thesis. First, I would like to thank Dr. Patricia Cherin, whose optimism, enthusiasm, and vision kept me moving toward a graduation date. Her encouragement as my thesis committee chair inspired me to work diligently towards completion. I am grateful to Abe Ravitz and Benito Gomez for being on my committee. Their thoughts and advice on the topics of American literature and film have been insightful and useful to my research. I would also like to thank my good friend, Caryn Houghton, who inspired me to start working on my master’s degree. Her assistance and encouragement helped me find time to work on my thesis despite overwhelming personal issues. I thank also my siblings, Brad Garren, and Jane Fawcett, who listened, loved and gave me the gift of quality time and encouragement. Other friends that helped me to complete this project in big and small ways include, Jenne Paddock, Lisa Morelock, Michelle Keliikuli, Michelle Blimes, Karma Whiting, Mark Lipset, and Shawn Chang. And, of course, I would like to thank my four beautiful children, Makena, T.K., Emerald, and Summer. They have taught me patience, love, and faith. They give me hope to keep living and keep trying. -

University Micrxxilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of "sectioning" the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

I Am Adele Bloch-Bauer, I Am Hester Prynne

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons All Theses & Dissertations Student Scholarship 2016 I AM ADELE BLOCH-BAUER, I AM HESTER PRYNNE Laurie Lico Albanese MFA University of Southern Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/etd Part of the Fiction Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, Nonfiction Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Lico Albanese, Laurie MFA, "I AM ADELE BLOCH-BAUER, I AM HESTER PRYNNE" (2016). All Theses & Dissertations. 279. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/etd/279 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I AM ADELE BLOCH-BAUER, I AM HESTER PRYNNE ____________ A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE STONECOAST MFA IN CREATIVE WRITING ___________ BY Laurie Lico Albanese June 2016 Abstract I AM ADELE BLOCH-BAUER, I AM HESTER PRYNNE is a compilation of fiction and nonfiction written at Stonecoast. This cross-genre thesis includes two excerpts from historical novels with female protagonists, and an essay on women’s historical fiction. For the study and creation of female-centered historical fiction I researched and wrote in a wide range of areas, both intellectual and temporal. First, I read and traced the emergence of female-focused American historical fiction that began with Nathaniel Hawthrne’s The Scarlet Letter, and continues today with historical fiction based in fact such as Lily King’s Euphoria and Paula McClain’s The Paris Wife and Circling the Sun. -

The Colonizing Force of Hawthorne's the Scarlet Letter

Laura “A” for Atlantic: Doyle The Colonizing Force of Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter In The Scarlet Letter, colonization just happens or, more accurately, has just happened. We might recall, by contrast, how Catharine Maria Sedgwick’s novel Hope Leslie elaborately narrates the sociopolitical process of making an Indian village into a native English spot. Hawthorne eclipses this drama of settlement. Although Haw- thorne, like Sedgwick, sets his plot of sexual crisis in the early colo- nial period of Stuart political crisis and English Civil War, he places these events in the distant backdrop, as remote from his seventeenth- century characters as his nineteenth-century readers. Meanwhile, he recasts Sedgwick’s whimsical heroine, Hope Leslie, as a sober, already arrived, and already fallen woman. In beginning from this already fallen moment, Hawthorne keeps off- stage both the “fall” of colonization and its sexual accompaniment. He thereby obscures his relationship to a long Atlantic literary and politi- cal history. But if we attend to the colonizing processes submerged in The Scarlet Letter, we discover the novel’s place in transatlantic his- tory—a history catalyzed by the English Civil War and imbued with that conflict’s rhetoric of native liberty. We see that Hawthorne’s text partakes of an implictly racialized, Atlantic ur-narrative, in which a people’s quest for freedom entails an ocean crossing and a crisis of bodily ruin. That is, The Scarlet Letter fits a formation reaching from Oroonoko, Moll Flanders, Charlotte Temple, and Olaudah -

What Literature Knows: Forays Into Literary Knowledge Production

Contributions to English 2 Contributions to English and American Literary Studies 2 and American Literary Studies 2 Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Kai Merten (eds.) Merten Kai / What Literature Knows This volume sheds light on the nexus between knowledge and literature. Arranged What Literature Knows historically, contributions address both popular and canonical English and Antje Kley US-American writing from the early modern period to the present. They focus on how historically specific texts engage with epistemological questions in relation to Forays into Literary Knowledge Production material and social forms as well as representation. The authors discuss literature as a culturally embedded form of knowledge production in its own right, which deploys narrative and poetic means of exploration to establish an independent and sometimes dissident archive. The worlds that imaginary texts project are shown to open up alternative perspectives to be reckoned with in the academic articulation and public discussion of issues in economics and the sciences, identity formation and wellbeing, legal rationale and political decision-making. What Literature Knows The Editors Antje Kley is professor of American Literary Studies at FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany. Her research interests focus on aesthetic forms and cultural functions of narrative, both autobiographical and fictional, in changing media environments between the eighteenth century and the present. Kai Merten is professor of British Literature at the University of Erfurt, Germany. His research focuses on contemporary poetry in English, Romantic culture in Britain as well as on questions of mediality in British literature and Postcolonial Studies. He is also the founder of the Erfurt Network on New Materialism. -

Logic Intertextuality in the Works of Siri Hustvedt and Paul Auster

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Reading to you, or the aesthetics of marriage : dia- logic intertextuality in the works of Siri Hustvedt and Paul Auster https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40315/ Version: Full Version Citation: Williamson, Alexander (2018) Reading to you, or the aesthet- ics of marriage : dialogic intertextuality in the works of Siri Hustvedt and Paul Auster. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email 1 Reading to You, or the Aesthetics of Marriage Dialogic Intertextuality in the Works of Siri Hustvedt and Paul Auster Alexander Williamson Doctoral thesis submitted in partial completion of a PhD at Birkbeck, University of London July 2017 2 Abstract Using a methodological framework which develops Vera John-Steiner’s identification of a ‘generative dialogue’ within collaborative partnerships, this research offers a new perspective on the bi-directional flow of influence and support between the married authors Siri Hustvedt and Paul Auster. Foregrounding the intertwining of Hustvedt and Auster’s emotional relationship with the embodied process of aesthetic expression, the first chapter traces the development of the authors’ nascent identities through their non-fictional works, focusing upon the autobiographical, genealogical, canonical and interpersonal foundation of formative selfhood. Chapter two examines the influence of postmodernist theory and poststructuralist discourse in shaping Hustvedt and Auster’s early fictional narratives, offering an alternative reading of Auster’s work outside the dominant postmodernist label, and attempting to situate the hybrid spatiality of Hustvedt and Auster’s writing within the ‘after postmodernism’ period. -

Female Anti-Heroes in Contemporary Literature, Film, and Television Sara A

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 Female Anti-Heroes in Contemporary Literature, Film, and Television Sara A. Amato Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Amato, Sara A., "Female Anti-Heroes in Contemporary Literature, Film, and Television" (2016). Masters Theses. 2481. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2481 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� f.AsTE�ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY" Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, andDistribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

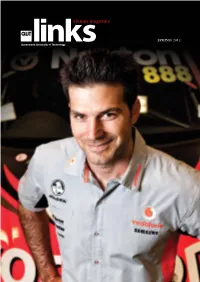

QUT Links Alumni Magazine Spring 2012

alumni magazine SPRING 2012 contentsVOLUME 15 NUMBER 2 Profiles Features Wayne Blair’s The QUT’s Outstanding Sapphires lauded by film Alumni Award winners 9 critics and audiences. 1-6 are revealed. Mother-daughter maths Welcome to the future teaching duo go bush. of interactive learning – 14 11 The Cube. Attorney General Jarrod Bleijie has legislative Bouquets of caring 15 reform on his agenda. recognise Queensland 20 community gems. 4 Student leader Erin Gregor is an impressive 19 all-rounder. Research Regulars New frontier opens for NEWS ROUNDUP 8 10 space glass. RESEARCH UPDATE 18 Rats inspire GPS camera ALUMNI NEWS 21-23 9 technology. 12 KEEP IN TOUCH 24 Heart attack care study LAST WORD rates towns nationwide. 13 by Vice-Chancellor Professor Peter Coaldrake Vice-Chancellor fellows lead the pack in - SEE INSIDE BACK COVER 16 innovative research. Transcend physical and spiritual limits 17 through sport. 17 alumni magazine links Editor Stephanie Harrington p: 07 3138 1150 e: [email protected] Contributors Rose Trapnell Alita Pashley Niki Widdowson Mechelle McMahon Rachael Wilson Images Erika Fish In focus Design Richard de Waal Philanthropist Tim Fairfax is QUT’s distinguished QUT Links is published by QUT’s 7 new Chancellor. Marketing and Communication Department in cooperation with QUT’s Alumni and Development Office. Editorial material is gathered from a range of sources and does not necessarily reflect the opinions and policies of QUT. CRICOS No. 00213J QUTLINKS SPRING ’12 1 Outstanding Young Alumnus Award Winner Mark Dutton Thinker WHEN reigning V8 Supercars champion Jamie Whincup speeds off at the start line, Mark Dutton’s FAST feet are planted firmly on the ground. -

Hawthorne's Conception of History: a Study of the Author's Response to Alienation from God and Man

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1979 Hawthorne's Conception of History: a Study of the Author's Response to Alienation From God and Man. Lloyd Moore Daigrepont Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Daigrepont, Lloyd Moore, "Hawthorne's Conception of History: a Study of the Author's Response to Alienation From God and Man." (1979). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3389. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3389 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

A Tentative Defense for the Villain Roger Chillingworth in the Scarlet Letter

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, July 2020, Vol. 10, No. 7, 575-583 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2020.07.008 D DAVID PUBLISHING A Tentative Defense for the Villain Roger Chillingworth in The Scarlet Letter ZHANG Bao-cang Beijinng Foreign Studies University;Henan Agricultural University, Henan, China The paper makes a tentative defense for the villain Roger Chillingworth in The Scarlet Letter, regarding that the characterization with a devil’s image, cruel and cold-blooded is related to religious and artistic purposes. Actually, with the truth shifted from religious to psychological one, textual evidence shows that Chillingworth is far from that bad, and as one of the protagonists, she also deserves the pity and sympathy from the reader. Keywords: Nathaniel Hawthorne, Roger Chillingworth, defense 1. Introduction As a man of letters, Nathaniel Hawthorne had struggled in literary circle for more than two decades in obscurity, before the publication of his masterpiece The Scarlet Letter (1850), which finally brought him both good reputation and profit with a soaring sale. With this work, it seems overnight Hawthorne was known to the public, as within ten days the work had a sale of 2500 copies, and in the next 14 years this book brought Hawthorne the profit as much as $1500. The Scarlet Letter, set in the 1640s New England, narrates the story of adultery and redemption of a young lady Hester Prynne. From the masterpiece, the reader will always generate an endless number of meanings from different perspectives. So far, scholars have conducted their researches from different perspectives, such as redemption of religion, feminism, Freud’s psychoanalysis, prototype theory and character analysis. -

The Scarlet Letter

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 5, No. 10, pp. 2164-2168, October 2015 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0510.26 A Brief Study on the Symbolic Meaning of the Main Characters’ Name in The Scarlet Letter Nan Lei Yangtze University, China Abstract—As a great romantic novelist in American literature in the 19th century and a central figure in the American Renaissance, Nathaniel Hawthorne is outstanding for his skillful employment of symbolism and powerful psychological insight. The Scarlet Letter, which is considered to be the greatest accomplishment of American short story and is often viewed as the first American symbolic and psychological novel, makes Nathaniel Hawthorne win incomparable position in American literature. With a brief introduction into The Scarlet Letter and a brief study on the two literary terms, i.e. symbol and symbolism, the paper attempts to expound Hawthorne’s skillful employment of symbolism in his masterpiece through the analysis of the symbolic meaning of the main characters’ name in this great novel. Index Terms—The Scarlet Letter, symbol, symbolism, character, name I. A BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO THE SCARLET LETTER The Scarlet Letter is the masterpiece of Nathaniel Hawthorne, one of the most significant and influential writers in American literature in the 19th century. It is also regarded as the first symbolic novel in American literature for Hawthorne’s skillful use of symbolism and allegory. In the novel, the settings (the scarlet letter A, the prison, the scaffold, the rosebush, the forest, the sunshine and the brook) and the characters’ images, words and names are all endowed with profound symbolic meaning by Hawthorne.