Prehypertension Increases the Risk for Renal Arteriosclerosis in Autopsies: the Hisayama Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Documentationand Coding Tips: Peripheral Vascular Disease

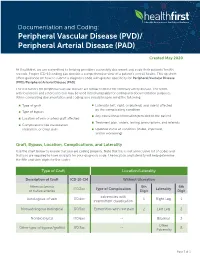

Documentation and Coding: Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD)/ Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD) Created May 2020 At Healthfirst, we are committed to helping providers accurately document and code their patients’ health records. Proper ICD-10 coding can provide a comprehensive view of a patient’s overall health. This tip sheet offers guidance on how to submit a diagnosis code with greater specificity for Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD)/Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD). The risk factors for peripheral vascular disease are similar to those for coronary artery disease. The terms arteriosclerosis and atherosclerosis may be used interchangeably for coding and documentation purposes. When completing documentation and coding, you should keep in mind the following: Type of graft Laterality (left, right, or bilateral) and side(s) affected by the complicating condition Type of bypass Any educational information provided to the patient Location of vein or artery graft affected Treatment plan, orders, testing, prescriptions, and referrals Complications like claudication, ulceration, or chest pain Updated status of condition (stable, improved, and/or worsening) Graft, Bypass, Location, Complications, and Laterality Use the chart below to ensure that you are coding properly. Note that this is not an inclusive list of codes and that you are required to have six digits for your diagnosis code. The location and laterality will help determine the fifth and sixth digits for the codes. Type of Graft Location/Laterality Description of Graft ICD-10-CM Without -

Association Between Multi-Site Atherosclerotic Plaques and Systemic Arteriosclerosis

Association between multi-site atherosclerotic plaques and systemic arteriosclerosis: results from the BEST study (Beijing Vascular Disease Patients Evaluation Study) huan liu Peking University Shougang Hospital https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6223-7677 Jinbo Liu Peking University Shougang Hospital Wei Huang Peking University Shougang Hospital Hongwei Zhao Peking University Shougang Hospital Na zhao Peking University Shougang Hospital Hongyu wang ( [email protected] ) Research Keywords: arteriosclerosis, atherosclerosis, atherosclerotic plaque, carotid femoral artery pulse wave velocity CF-PWV Posted Date: June 8th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-31641/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published on August 1st, 2020. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s12947-020-00212-3. Page 1/18 Abstract Background Arteriosclerosis can be reected in various aspect of the artery, including atherosclerotic plaque formation or stiffening on the arterial wall. Both arteriosclerosis and atherosclerosis are important and closely associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD). The aim of the study was to evaluate the association between systemic arteriosclerosis and multi-site atherosclerotic plaques. Methods The study was designed as an observational cross-sectional study. A total of 1178 participants (mean age 67.4 years; 52.2% male) enrolled into the observational study from 2010 to 2017. Systemic arteriosclerosis was assessed by carotid femoral artery pulse wave velocity (CF-PWV) and multi-site atherosclerotic plaques (MAP, >=2 of the below sites) were reected in the carotid or subclavian artery, abdominal aorta and lower extremities arteries using ultrasound equipment. -

Peripheral Vascular Disease Becomes Increasingly Prevalent with by the Symptom Or Complication (E.G

SePTeMBer 2010 Informative and educational updates for providers FOCUS ON: PerIPherAl Always… • Document the cause of the peripheral arterial disease, VASCUlAr DISeASe if known, as well as the complication (e.g. PAD due to diabetes with ulcer lower leg). • Document arteriosclerosis as “arteriosclerosis of” and the site, “arteriosclerotic” or “arteriosclerosis with,” followed Peripheral vascular disease becomes increasingly prevalent with by the symptom or complication (e.g. arteriosclerosis of age. As such this is a growing concern in the United States given the the lower extremities with rest pain, arteriosclerosis of growing proportion of older adults. Based on a NhANeS report the the lower extremities with ulceration), not the symptom incidence can be as high as 15 to 17% in the population aged 70 and or complication alone. over. Documentation and Coding Tips4 The concern around peripheral vascular disease is several fold: Only a minority of patients may present with the classic symptoms of • “Peripheral arterial disease,” “peripheral vascular disease” limb claudication or ischemia. In one study only about 11 percent of and “intermittent claudication” are coded to 443.9 – the patients with PVD presented with classic symptoms.1 In another Peripheral vascular disease, unspecified. study as many as 28 percent of patients with peripheral vascular • Atherosclerosis of the native arteries of the extremities is disease were found to be physically inactive sometimes due to other coded based on documentation of the condition with the illness thereby precluding the development of symptoms.2 There is a symptom or complication: significant overlap of peripheral vascular disease with coronary artery 440.20 – Atherosclerosis of the extremities, unspecified disease, cerebrovascular disease and abdominal aortic aneurysms. -

Intracranial Vertebral Artery Dissection in Wallenberg Syndrome

Intracranial Vertebral Artery Dissection in Wallenberg Syndrome T. Hosoya, N. Watanabe, K. Yamaguchi, H. Kubota, andY. Onodera PURPOSE: To assess the prevalence of vertebral artery dissection in Wallenberg syndrome. METHODS: Sixteen patients (12 men, 4 women; mean age at ictus, 51 .6 years) with symptoms of Wallenberg syndrome and an infarction demonstrated in the lateral medulla on MR were reviewed retrospectively. The study items were as follows: (a) headache as clinical signs, in particular, occipitalgia and/ or posterior neck pain at ictus; (b) MR findings, such as intramural hematoma on T1-weighted images, intimal flap on T2-weighted images, and double lumen on three-dimensional spoiled gradient-recalled acquisition in a steady state with gadopentetate dimeglumine; (c) direct angiographic findings of dissection, such as double lumen, intimal flap, and resolution of stenosis on follow-up angiography; and (d) indirect angiographic findings of dissection (such as string sign, pearl and string sign, tapered narrowing, etc). Patients were classified as definite dissection if they had reliable MR findings (ie, intramural hematoma, intimal flap, and enhancement of wall and septum) and/ or direct angiographic findings; as probable dissection if they showed both headache and suspected findings (ie, double lumen on 3-D spoiled gradient-recalled acquisition in a steady state or indirect angiographic findings) ; and as suspected dissection in those with only headache or suspected findings. RESULTS: Seven of 16 patients were classified as definite dissection, 3 as probable dissection, and 3 as suspected dissection. Four patients were considered to have bilateral vertebral artery dissection on the basis of MR findings. CONCLUSIONS: Vertebral artery dissection is an important cause of Wallenberg syndrome. -

Doppler Ultrasound Exam of an Arm Or Leg Doppler Ultrasound Exam of an Arm Or Leg

30/07/2019 Doppler ultrasound exam of an arm or leg Doppler ultrasound exam of an arm or leg Definition This test uses ultrasound to look at the blood flow in the large arteries and veins in the arms and legs. Alternative Names Peripheral vascular disease - Doppler; PVD - Doppler; PAD - Doppler; Blockage of leg arteries - Doppler; Intermittent claudication - Doppler; Arterial insufficiency of the legs - Doppler; Leg pain and cramping - Doppler; Calf pain - Doppler; Venous Doppler - DVT How the Test is Performed The test is done in the ultrasound or radiology department or in a peripheral vascular lab. During the exam: A water-soluble gel is placed on a handheld device called a transducer. This device directs high-frequency sound waves to the artery or veins being tested. Blood pressure cuffs may be put around different parts of the body, including the thigh, calf, ankle, and different points along the arm. A paste is applied to the skin over the arteries or veins being examined. Images are created as the transducer is moved over each area. How to Prepare for the Test You will need to remove clothes from the arm or leg being examined. How the Test will Feel Sometimes, the person performing the test will need to press on the vein to make sure it does not have a clot. Some people may feel slight pain. Why the Test is Performed This test is done as the first step to look at arteries and veins. Sometimes, arteriography and venography may be needed later. The test is done to help diagnose: Arteriosclerosis of the arms or legs Blood clot (deep vein thrombosis) Venous insufficiency The test may also be used to: Look at injury to the arteries Monitor arterial reconstruction and bypass grafts Normal Results printer-friendly.adam.com/content.aspx?print=1&productId=117&pid=1&gid=003775&c_custid=1549 1/2 30/07/2019 Doppler ultrasound exam of an arm or leg A normal result means the blood vessels show no signs of narrowing, clots, or closure, and the arteries have normal blood flow. -

RAYNAUD's SYNDROME MEDICAL APPENDIX DEFINITION 1. Raynaud's Syndrome Is a Disorder Characterised by Intermittent Short-Lasti

RAYNAUD’S SYNDROME MEDICAL APPENDIX DEFINITION 1. Raynaud’s syndrome is a disorder characterised by intermittent short-lasting inappropriate spasm of the arterioles of the distal limbs following exposure to cold or emotional stimuli. 2. The term includes on the one hand cases in which a precise cause has not been clearly defined (primary Raynaud’s syndrome, Raynaud’s disease, idiopathic episodic digital vasospasm) and on the other, cases where the disorder or secondary to some systemic illness or disease process (secondary Raynaud’s syndrome, Raynaud’s phenomenon). CLINICAL FEATURES 3. The classic manifestation is a triphasic colour response of abrupt onset, consisting first of blanching, or pallor, due to constriction of the small arteries (vasospasm), then cyanosis due to stasis of the blood as the vasoconstriction becomes less severe, and finally the flush of reactive hyperaemia as the blood supply is restored. The affected part therefore turns white, then blue and finally red. The attack is frequently associated with numbness of the affected areas and typically lasts from a few minutes to half an hour. 4. Episodes are usually precipitated by exposure to a cool environment, although in some patients they may be triggered by emotional stress. The application of heat shortens the attack, and recovery is often accompanied by pain and throbbing. 5. In the great majority of patients, the fingers are the initial site of involvement. At first, only the tips of one or two fingers are involved in the attacks but later, colour changes may develop in additional fingers. In some 40 per cent of patients the toes are also affected and rarely, the tip of the nose or lobes of the ears. -

Exhibit at Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology | Peripheral Vascular Disease Scientific Sessions

SPECIALTY CONFERENCES EXHIBIT AT ARTERIOSCLEROSIS, THROMBOSIS AND VASCULAR BIOLOGY | PERIPHERAL VASCULAR DISEASE SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS • Get one-on-one with more clinicians and research scientists in this intimate meeting environment. • Meet important decision-makers: 87% of attendees are clinicians and/or research scientists. • 80% of Specialty Conference exhibitors say they will exhibit again next year. Exhibit Dates & Location CONFERENCE SUMMARY May 9-12, 2018 This three-day meeting is sponsored and organized by the AHA Councils on Hilton San Francisco Union Square Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology and Peripheral Vascular Disease, and San Francisco, CA in collaboration with the AHA Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology and the Society for Vascular Surgery. The meeting includes diverse disciplines within the Exhibit Rates arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, vascular biology, vascular medicine, functional genomics, $500 (nonprofi t) peripheral vascular disease and vascular surgery research communities that allow $1,500 (industry) investigators to explore areas of cross-disciplinary interests. Tabletops include: TARGET AUDIENCE • One 6’x30” table with two chairs • One company identifi cation sign and The conference will especially appeal to basic scientists, translational and clinical trash can investigators, and clinicians interested in vascular health, vascular medicine, • Two conference badges atherosclerosis, vascular biology, thrombosis, vascular surgery, thromboembolism, peripheral artery disease, molecular/cellular biology, functional genomics, immunology and physiology. ATTENDANCE ENHANCE YOUR MEETING • 87% are clinicians and/or research scientists. PRESENCE AND DRIVE • 28% of attendees are International. ATTENDANCE TO YOUR • Specialties include Arteriosclerosis, Biochemistry, Cardiology, Cell Biology, Diabetes and Metabolism, Endocrinology, Epidemiology, Genetics, Hematology, Hypertension, BOOTH WITH OFFICIAL Imaging, Internal Medicine, Interventional Cardiology, Molecular Biology, Nutrition, MARKETING OPPORTUNITIES. -

Peripheral Vascular Disease Other Names: Peripheral Arterial Disease, Arteriosclerosis, Atherosclerosis What Is Peripheral Vascu

Peripheral Vascular Disease Other names: Peripheral Arterial Disease, Arteriosclerosis, Atherosclerosis What is peripheral vascular disease? Peripheral vascular disease refers to the narrowing, clogging and hardening of the arteries in your extremities. This results in slowed or stopped blood flow to your extremities, which can cause pain, numbness, and eventually tissue death in your extremities. The disease frequently affects your legs, but can occur in the vessels that supply blood to your arms, brain, and kidneys. There are many things you can do to reduce your risk of peripheral vascular disease, and to treat the disorder and symptoms if it occurs. Pain and numbness in your extremities is not a normal part of the aging process, and should be addressed. What Causes peripheral vascular disease? Atherosclerosis is caused when fatty substances (cholesterol and scar tissue, sometimes called "plaque") build up inside the artery walls over time and create an blockage that restricts blood flow. The vessel walls become less elastic and cannot dilate to allow greater blood flow when needed (such as during exercise). Deposits of calcium in the walls of the arteries contribute to the narrowing and stiffness; this calcification may be visible on plain X-rays. Symptoms of peripheral vascular disease also can develop when a blood clot forms in the artery. Who is at risk for peripheral vascular disease? Peripheral vascular disease is a common disorder. It affects men more often than women. It occurs most often in people who are over 50. However, anyone can develop the disorder. If you smoke, are overweight, or have high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol, or a family history of heart or vascular disease, your risk of developing peripheral vascular disease increases. -

Arteriosclerosis Overview: • It Refers to the Buildup of Fats, Cholesterol, and Other Substances in the Arteries, Which Can Restrict Blood Flow

Arteriosclerosis Overview: • It refers to the buildup of fats, cholesterol, and other substances in the arteries, which can restrict blood flow. • Arteriosclerosis often leads to serious heart problems; it can also affect arteries anywhere in your body. • The risk of arteriosclerosis can be lowered by managing some of the following risk factors: family history, obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, smoking, and foods rich in saturated fats. • Early diagnosis and treatment can stop arteriosclerosis from worsening. • Lifestyle changes are often the most appropriate treatment and prevention method recommended for arteriosclerosis. Introduction: Arteries are blood vessels that carry oxygen-rich blood to your heart and other parts of your body. The term arteriosclerosis refers to the buildup of oxidized fatty substances and plaque on the arterial walls, restricting blood flow to the body’s organs. Arteriosclerosis can affect arteries anywhere in the body, including the heart, brain, arms, legs, pelvis, and kidneys. Depending on which arteries are blocked, arteriosclerosis can lead to several diseases, such as: • Coronary artery disease. • Heart attack. • Carotid artery disease. • Peripheral artery disease. • Chronic kidney disease. It can also leads to serious problems or even death. Cause: Arteriosclerosis is caused by the buildup of fats, cholesterol, and other substances in the arteries. However, it is still unknown exactly how it begins or what causes it. Arteriosclerosis is a slow, progressive vascular disease that may start as early as childhood and then progress more rapidly with age. Risk Factors: • Advanced age. • Family history of early heart disease. • High blood cholesterol. • Inactivity. • An unhealthy diet. • Insulin resistance. • High blood pressure. -

Arteriosclerosis, Atherosclerosis, Arteriolosclerosis, and Monckeberg Medial Calcific Sclerosis: What Is the Difference?

ARTIGO DE REVISÃO ISSN 1677-7301 (Online) Arteriosclerose, aterosclerose, arteriolosclerose e esclerose calcificante da média de Monckeberg: qual a diferença? Arteriosclerosis, atherosclerosis, arteriolosclerosis, and Monckeberg medial calcific sclerosis: what is the difference? Vanessa Prado dos Santos1 , Geanete Pozzan2, Valter Castelli Júnior2, Roberto Augusto Caffaro2 Resumo A principal causa de óbito na contemporaneidade são as doenças cardiovasculares. Arteriosclerose, aterosclerose, arteriolosclerose e arteriosclerose de Monckeberg são termos frequentemente utilizados como sinônimos, mas traduzem alterações distintas. O objetivo desta revisão foi discutir os conceitos de arteriosclerose, aterosclerose, arteriolosclerose e esclerose calcificante da média de Monckeberg. O termo arteriosclerose é considerado mais genérico, significando o enrijecimento e a consequente perda de elasticidade da parede arterial, abarcando os demais tipos. A aterosclerose é uma doença inflamatória secundária a lesões na camada íntima, que tem como principal complicação obstrução crônica e aguda do lúmen arterial. A arteriolosclerose se refere ao espessamento das arteríolas, particularmente relacionada à hipertensão arterial sistêmica. Já a esclerose calcificante da média de Monckeberg designa a calcificação, não obstrutiva, da lâmina elástica interna ou da túnica média de artérias musculares. As calcificações vasculares, que incluem lesões ateroscleróticas e a esclerose calcificante da média de Monckeberg, vêm sendo estudadas como um fator de risco para -

A Review on the Value of Imaging in Differentiating Between Large Vessel Vasculitis and Atherosclerosis

Journal of Personalized Medicine Review A Review on the Value of Imaging in Differentiating between Large Vessel Vasculitis and Atherosclerosis Pieter H. Nienhuis 1,* , Gijs D. van Praagh 1 , Andor W. J. M. Glaudemans 1, Elisabeth Brouwer 2 and Riemer H. J. A. Slart 1,3 1 Department of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, Medical Imaging Center, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, 9700 RB Groningen, The Netherlands; [email protected] (G.D.v.P.); [email protected] (A.W.J.M.G.); [email protected] (R.H.J.A.S.) 2 Department of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, 9700 RB Groningen, The Netherlands; [email protected] 3 Department of Biomedical Photonic Imaging, Faculty of Science and Technology, University of Twente, 7500 AE Enschede, The Netherlands * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Imaging is becoming increasingly important for the diagnosis of large vessel vasculitis (LVV). Atherosclerosis may be difficult to distinguish from LVV on imaging as both are inflammatory conditions of the arterial wall. Differentiating atherosclerosis from LVV is important to enable optimal diagnosis, risk assessment, and tailored treatment at a patient level. This paper reviews the current evidence of ultrasound (US), 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to distinguish LVV from atherosclerosis. In this review, we identified a total of eight studies comparing LVV patients Citation: Nienhuis, P.H.; van Praagh, to atherosclerosis patients using imaging—four US studies, two FDG-PET studies, and two CT G.D.; Glaudemans, A.W.J.M.; studies. -

THE MORPHOLOGY, TERMINOLOGX, and PATHOGENESIS of ARTERIAL PLAQUES C.Uj

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.38.435.25 on 1 January 1962. Downloaded from POSTGRAD MED. J. (I962), 38, 25 THE MORPHOLOGY, TERMINOLOGX, AND PATHOGENESIS OF ARTERIAL PLAQUES C.uJ. SCHWARTZ,'M.D. AND J. R. A. MITCHELL, M.B., B.Sc., MJ.C.P. Department of the Regius Professor of Medicine, Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford ... a scientific survey which is to throw light on yellow pultaceous material. It is in this sense that theproblem ofarteriosclerosis in all its various aspects atheroma has been recently defined by WHO must be based upon a clear delimitation of that term'. (I958) as a' . plaque in which fatty softening is -Aschoff (1933). predominant'. All w9uld be well if workers were THE lack of precision of terms such as arterio- to limit its use to a particular type of plaque, but sclerosis, atheroma and atherosclerosis was em- atheroma, atherosclerosis and arteriosclerosis are phasized by Rabson (I954), who showed that they currently used as synonyms for a wide variety of have different meanings for different pathologists, arterial lesions. These terms, therefore, lack a and they are used to describe widely different types clear and reproducible meaning. of lesions, including many bizarre varieties of We considered, therefore, that an attempt experimentally induced arterial disease. should be made to describe the range of macro- Lobstein (I833) first coined the word arterio- scopic plaques which can be recognized on the sclerosis, which he applied as a generic term to all intimal surface of the major arteries (aorta, forms of arterial hardening. From its inception, carotid, iliac) and define the histological characteristics of by copyright.