Christos S. Zerefos (Referee) Human Volcano Relationships Have Been

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plate Tectonics, Volcanoes, and Earthquakes / Edited by John P

ISBN 978-1-61530-106-5 Published in 2011 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010. Copyright © 2011 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved. Rosen Educational Services materials copyright © 2011 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services. For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932. First Edition Britannica Educational Publishing Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor J. E. Luebering: Senior Manager Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition John P. Rafferty: Associate Editor, Earth Sciences Rosen Educational Services Alexandra Hanson-Harding: Editor Nelson Sá: Art Director Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager Nicole Russo: Designer Matthew Cauli: Cover Design Introduction by Therese Shea Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Plate tectonics, volcanoes, and earthquakes / edited by John P. Rafferty. p. cm.—(Dynamic Earth) “In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.” Includes index. ISBN 978-1-61530-187-4 ( eBook) 1. Plate tectonics. -

Review of Local and Global Impacts of Volcanic Eruptions and Disaster Management Practices: the Indonesian Example

geosciences Review Review of Local and Global Impacts of Volcanic Eruptions and Disaster Management Practices: The Indonesian Example Mukhamad N. Malawani 1,2, Franck Lavigne 1,3,* , Christopher Gomez 2,4 , Bachtiar W. Mutaqin 2 and Danang S. Hadmoko 2 1 Laboratoire de Géographie Physique, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, UMR 8591, 92195 Meudon, France; [email protected] 2 Disaster and Risk Management Research Group, Faculty of Geography, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta 55281, Indonesia; [email protected] (C.G.); [email protected] (B.W.M.); [email protected] (D.S.H.) 3 Institut Universitaire de France, 75005 Paris, France 4 Laboratory of Sediment Hazards and Disaster Risk, Kobe University, Kobe City 658-0022, Japan * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This paper discusses the relations between the impacts of volcanic eruptions at multiple- scales and the related-issues of disaster-risk reduction (DRR). The review is structured around local and global impacts of volcanic eruptions, which have not been widely discussed in the literature, in terms of DRR issues. We classify the impacts at local scale on four different geographical features: impacts on the drainage system, on the structural morphology, on the water bodies, and the impact Citation: Malawani, M.N.; on societies and the environment. It has been demonstrated that information on local impacts can Lavigne, F.; Gomez, C.; be integrated into four phases of the DRR, i.e., monitoring, mapping, emergency, and recovery. In Mutaqin, B.W.; Hadmoko, D.S. contrast, information on the global impacts (e.g., global disruption on climate and air traffic) only fits Review of Local and Global Impacts the first DRR phase. -

The Year Without a Summer

The Year Without a Summer In 1816, half a foot of snow fell in New England. That would be Mount Tambora, an active completely unremarkable. Except that it was in one day—in June. stratovolcano that is a peninsula of and the highest That same summer, Mary Shelley spent a chilly vacation holed peak on the island of up indoors—and used the time to write Frankenstein. Crops Sumbawa in Indonesia. failed around the world, plunging Thomas Jefferson into serious Credit: Jialiang Gao (peace-on- debt for the rest of his life. Oats became scarce in Germany, earth.org) via Wikimedia Commons making horse travel expensive—and leading to the invention (CC BY-SA 3.0 [http://creative- of the bicycle. Struggling farmers in China began raising opium, commons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0]) giving rise to a drug trade that has lasted to modern times. And famine in many areas led to widespread disease, including a cholera outbreak that killed millions. What was the cause of all this chaos? A year earlier, a volcano erupted in Indonesia. Larger than Krakatoa, Vesuvius, or Mount St. Helens, Mount Tambora erupted for 2 weeks straight. Around it, nearly 100,000 people died, buried under thick layers of ash like in Pompeii. Greenhouse-gas emissions from the eruption, which could have warmed the atmosphere, were offset by particulates and sulfur dioxide gas. Ash and dust blocked out the sun temporarily, darkening skies around the world. The sulfur dioxide was longer-lasting, becoming aerosols that reflected the sun’s heat for 3 years! This turned 1816 into “The Year Without a Summer,” as it was called, with long-term global effects. -

How Mount Agung's Eruption Can Create the World's Most Fertile Soil

How Mount Agung's eruption can create the world's most fertile soil https://theconversation.com/how-mount-agungs-eruption-can-create-the... Disiplin ilmiah, gaya jurnalistik How Mount Agung’s eruption can create the world’s most fertile soil Oktober 5, 2017 3.58pm WIB Balinese farmers with Mount Agung in the background. Areas with high volcanic activity also have some of the world’s most fertile farmlands. Reuters/Darren Whiteside Mount Agung in Bali is currently on the verge of eruption, and more than 100,000 Penulis people have been evacuated. However, one of us (Dian) is preparing to go into the area when it erupts, to collect the ash. This eruption is likely to be catastrophic, spewing lava and ashes at temperatures up to Budiman Minasny 1,250℃, posing serious risk to humans and their livelihoods. Ash ejected from volcano Professor in Soil-Landscape Modelling, not only affects aviation and tourism, but can also affect life and cause much nuisance to University of Sydney farmers, burying agricultural land and damaging crops. However, in the long term, the ash will create world’s most productive soils. Anthony Reid Emeritus Professor, School of Culture, 1 of 5 10/7/2017, 5:37 AM How Mount Agung's eruption can create the world's most fertile soil https://theconversation.com/how-mount-agungs-eruption-can-create-the... History and Language, Australian National University Dian Fiantis Professor of Soil Science, Universitas Andalas Alih bahasa Bahasa Indonesia English Read more: Bali’s Mount Agung threatens to erupt for the first time in more than 50 years While volcanic soils only cover 1% of the world’s land surface, they can support 10% of the world’s population, including some areas with the highest population densities. -

Educators Guide

EDUCATORS GUIDE 02 | Supervolcanoes Volcanism is one of the most creative and destructive processes on our planet. It can build huge mountain ranges, create islands rising from the ocean, and produce some of the most fertile soil on the planet. It can also destroy forests, obliterate buildings, and cause mass extinctions on a global scale. To understand volcanoes one must first understand the theory of plate tectonics. Plate tectonics, while generally accepted by the geologic community, is a relatively new theory devised in the late 1960’s. Plate tectonics and seafloor spreading are what geologists use to interpret the features and movements of Earth’s surface. According to plate tectonics, Earth’s surface, or crust, is made up of a patchwork of about a dozen large plates and many smaller plates that move relative to one another at speeds ranging from less than one to ten centimeters per year. These plates can move away from each other, collide into each other, slide past each other, or even be forced beneath each other. These “subduction zones” are generally where the most earthquakes and volcanoes occur. Yellowstone Magma Plume (left) and Toba Eruption (cover page) from Supervolcanoes. 01 | Supervolcanoes National Next Generation Science Standards Content Standards - Middle School Content Standards - High School MS-ESS2-a. Use plate tectonic models to support the HS-ESS2-a explanation that, due to convection, matter Use Earth system models to support cycles between Earth’s surface and deep explanations of how Earth’s internal and mantle. surface processes operate concurrently at different spatial and temporal scales to MS-ESS2-e form landscapes and seafloor features. -

Sertifikat Klik Artikel Daftar Isi Sampul << Kembali

ii CONTENTS 1. Welcome messages: a. Rector of Brawijaya University b. Dean of faculty of medicine c. Committee’s welcome 2. The ICON 2 Committee 2016 3. Keynote speakers profile 4. Oral presentation schedule 5. Poster presentation schedule 6. Abstracts and full texts of oral presentations 7. Abstracts and full texts of poster presentations i Rector’s welcome Assalamualaikumwarohmatullahiwabarokatuh Good morning, may god always give us good health, bright mind and sincere heart First of all I would like to say thank you to all the distinguished speakers: 1. Minister of Health of The Republic of Indonesia 2. Minister of Manpower of The Republic of Indonesia 3. Dr. Ati Surya Mediawati, S.Kp, M.Kep, head of nursing department of the Indonesian National Nurses Association 4. Dr (c) Asti Melani Astari, lecturer as well as maternity nurse specialist (Brawijaya University) 5. Nadin M. Abdel Razeeq, PhD, RN (University of Jordan) 6. Associate.Prof. Lorena Baccaglini, PhD (University of Nebraska Medical Center, USA) 7. John Francis Jr Faustorilla, DNS, RN (St. Dominic College of Asia University, Filipina) Ladies and gentlemen, I would like to say welcome to Malang city, the city of education where our university is located. On behalf of the Brawijaya University I honestly extend my gratitude to all of you for your enthusiasm and effort to join this annual event. It is a great honor for us to have you all here to share knowledge, experience as well as ideas and thought to improve our understanding about high quality health practice. CurrrentlyBrawijaya University is on the top six universities in Indonesia. -

TEACHING MODULE for ENGLISH for SPECIFIC PURPOSES

TEACHING MODULE for ENGLISH FOR SPECIFIC PURPOSES Compiled By Bertaria Sohnata Hutauruk Only for our classroom instructions (Very restricted use) FKIP UHN PEMATANGSIANTAR 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This binding is a result of compilation from the authentic material from the webs. It is a result of short browsing. The aim is to provide a suitable module for our ESP classroom sessions in the first semester of the 2011/2012 academic year in our study program. This module consists of some lessons for the concept of ESP, some lessons for ESP lesson plans used abroad and in Indonesia, ESP for some school levels, and ESP for Academic Purposes and for Occupational Purposes. The main teaching objective in our classroom is to provide the students with the competence on designing a good lesson plan to teach ESP for academic purposes and occupational purposes at any level according to its context. We fully intend that this binding is only to facilitate some compiled authentic materials from the webs for our ESP Classroom instructions. By this opportunity, we would like to extend our sincere thanks all the authors of the materials and the websites which publish them. May God the Almighty bless them all! Medan-Pematangsiantar, September 2015 The Authors, Bertaria Sohnata Hutauruk TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT…………………………………………………………… TABLE OF CONTENTS…………………………………………………………….. Lesson 1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………….. Lesson 2 ESP AND ESL………………………………………………………………………. Leson 3 ESP Course at Technical Secondary Vocational School for Construction and Building Trade students………………………………………. Lesson 4 ESP Vocabulary Teaching at the Vocational Secondary School of Furniture Industry………………………….. Lesson 5 ESP International Sample lesson plan........................................................................... Lesson 6 ESP Lesson Plan in Indonesia……………………………………………………….. -

Environment, Trade and Society in Southeast Asia

Environment, Trade and Society in Southeast Asia <UN> Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte (kitlv, Leiden) Henk Schulte Nordholt (kitlv, Leiden) Editorial Board Michael Laffan (Princeton University) Adrian Vickers (Sydney University) Anna Tsing (University of California Santa Cruz) VOLUME 300 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/vki <UN> Environment, Trade and Society in Southeast Asia A Longue Durée Perspective Edited by David Henley Henk Schulte Nordholt LEIDEN | BOSTON <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC-BY-NC 3.0) License, which permits any non-commercial use, distri- bution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of kitlv (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: Kampong Magetan by J.D. van Herwerden, 1868 (detail, property of kitlv). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Environment, trade and society in Southeast Asia : a longue durée perspective / edited by David Henley, Henk Schulte Nordholt. pages cm. -- (Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde ; volume 300) Papers originally presented at a conference in honor of Peter Boomgaard held August 2011 and organized by Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-28804-1 (hardback : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-28805-8 (e-book) 1. Southeast Asia--History--Congresses. 2. Southeast Asia--Civilization--Congresses. -

Processes of Policy Mobility in the Governance of Volcanic Risk

1 Processes of Policy Mobility in the Governance of Volcanic Risk Graeme Alexander William Sinclair Lancaster Environment Centre Lancaster University Lancaster LA1 4YQ UK Submitted 2019 This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 2 Statement of Declaration I hereby declare that the content of this PhD thesis is my own work except where otherwise specified by reference or acknowledgement, and has not been previously submitted for any other degree or qualification. Graeme A.W. Sinclair 3 Abstract —National and regional governments are responsible for the development of public policy for volcanic risk reduction (VRR) within their territories. However, practices vary significantly between jurisdictions. A priority of the international volcanological community is the identification and promotion of improved VRR through collaborative knowledge exchange. This project investigates the role of knowledge exchange in the development of VRR. The theories and methods of policy mobility studies are used to identify and explore how, why, where and with what effects international exchanges of knowledge have shaped this area of public policy. Analyses have been performed through the construction of narrative histories. This project details the development of social apparatus for VRR worldwide, depicted as a global policy field on three levels - the global (macro) level; the national (meso) level; and at individual volcanoes (the micro level). The narratives track the transition from a historical absence of VRR policy through the global proliferation of a reactive 'emergency management' approach, to the emergence of an alternative based on long-term planning and community empowerment that has circulated at the macro level, but struggled to translate into practice. -

Multivariate Approaches to Infer Volcanic System Parameters, Timing, and Size of Explosive Eruptions

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Multivariate approaches to infer volcanic system parameters, timing, and size of explosive eruptions Manta, Fabio 2019 Manta, F. (2019). Multivariate approaches to infer volcanic system parameters, timing, and size of explosive eruptions. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/107577 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/107577 Downloaded on 06 Oct 2021 22:15:36 SGT MULTIVARIATE APPROACHES TO INFER VOLCANIC SYSTEM PARAMETERS, TIMING, AND SIZE OF EXPLOSIVE ERUPTIONS FABIO MANTA ASIAN SCHOOL OF THE ENVIRONMENT 2019 MULTIVARIATE APPROACHES TO INFER VOLCANIC SYSTEM PARAMETERS, TIMING, AND SIZE OF EXPLOSIVE ERUPTIONS Fabio Manta Asian School of the Environment Nanyang Technological University A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 I II Candidate Statement of Originality I hereby certify that the work embodied in this thesis is the result of original research, is free of plagiarised materials, and has not been submitted for a higher degree to any other University or Institution. I confirm that the investigations were conducted in accord with the ethics policies and integrity standards of Nanyang Technological University and that the research data are presented honestly and without prejudice. 10/07/2019 . Date Fabio Manta III IV Supervisor Declaration Statement I have reviewed the content and presentation style of this thesis and declare it is of sufficient quality and grammatical clarity to be examined. To the best of my knowledge, it is free of plagiarism and the research and writing are those of the candidate except as acknowledged in the Author Attribution Statement. -

The Tambora – Frankenstein Myth: the Monster Inspired Alan Marshall

The Tambora – Frankenstein Myth: The Monster Inspired Alan Marshall, Kanang Kantamurapoj, Nanthawan Kaenkaew, Mark Felix Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Mahidol University 999 Phuttamonthon 4, Nakhonpathum 73710, Thailand Email: [email protected] Abstract: The link between the volcanic eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815 and Mary Shelley’s composition of Frankenstein has attained mythic status. The myth uses a scientific frame to promote the idea that the Tambora event led to Mary Shelley’s invention of the Frankenstein story because the eruption so altered the climate of Europe (lowering the temperatures, creating rainy electrical storms, producing frosts and floods, and generally darkening the landscape) that Shelley dreamt up the idea for her monstrous horror tale as a result. She was then imprisoned indoors by the volcanically-induced bad summer weather of 1816 and thus encouraged to craft the story into a full length gothic novel. This paper outlines the structure of this Tambora – Frankenstein myth and then attempts to investigate its roles, goals, and meanings as ascribed by various (mostly ‘pop science’ scholars) and journalists. An attempt is then made to elucidate the problems, failings, and miscalculations of the Myth. Keywords: Frankenstein volcano; scientific myth; science fiction; gothic literature. Introduction In April 1815, on the island of Sumbawa in the East Indies, the 14,000 foot Tambora volcano underwent a massive eruption. Geologists now believe it was the biggest eruptive event in recorded history, thousands of times stronger than the eruptions of Mt St Helens (1980) or Vesuvius (79AD) and some ten to twenty times stronger than the famous Krakatoa eruption of 1883.1 The Tambora eruption was so loud that many hundreds of miles away the British Governor of Java, Stamford Raffles, thought that an enemy fleet might have started a cannon battle somewhere off the coast.2 The eruption spewed up to 175 cubic kilometers of hot dusty ashy material into the sky to a height of some 40 kilometers. -

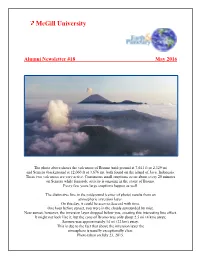

Alumni Newsletter No. 18

McGill University Alumni Newsletter #18 May 2016 The photo above shows the volcanoes of Bromo (mid-ground at 7,641 ft or 2,329 m) and Semeru (background at 12,060 ft or 3,676 m), both found on the island of Java, Indonesia. These two volcanoes are very active. Continuous small eruptions occur about every 20 minutes on Semeru while fumarole activity is ongoing in the crater of Bromo. Every few years large eruptions happen as well. The distinctive line in the midground (center of photo) results from an atmospheric inversion layer. On this day, it could be seen to descend with time. One hour before sunset, you were in the clouds surrounded by mist. Near sunset, however, the inversion layer dropped below you, creating this interesting line effect. It might not look like it, but the cone of Bromo was only about 2.5 mi (4 km) away; Semuru was approximately 14 mi (22 km) away. This is due to the fact that above the inversion layer the atmosphere is usually exceptionally clear. Photo taken on July 23, 2015. Note from the Chair Good news coming our way as we anxiously greet the arrival of Spring. After a number of years of budget cuts in education, funding of education has become a priority at both the Provincial and Federal levels and instead of facing further budget cuts, as the McGill administration had anticipated and planned for for the 2017 fiscal year, we can expect some reinvestments in post- secondary education. Like every other academic unit within the University, the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences suffered over the last few years, mostly through the loss of support staff, but we have fared better than most thanks to the generosity of our many donors, alumni and friends.