Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal Petalidi of Messinia

Coastal Petalidi of Messinia Plan Days 3 A three days trip with beautiful beaches, hiking, magical castles and ancient cultures combined with accommodation in the traditional Stone Built Houses of Moorea Houses. By: Christina Koraki PLAN SUMMARY Day 1 1. Moorea - Christina & Gabriella Houses Accommodation 2. Ancient Messini Culture/Archaelogical sites 3. Archaeological Museum of Ancient Messene Culture/Museums 4. Pamisos Nature/Rivers 5. Archaeological Museum of Kalamata Culture/Museums 6. Tzanes Nature/Beaches 7. Moorea - Christina & Gabriella Houses Accommodation Day 2 1. Moorea - Christina & Gabriella Houses Accommodation 2. Pylos Castle (Niokastro) Culture/Castles 3. Voidokilia Nature/Beaches 4. Methoni Castle Culture/Castles 5. Polylimnio Nature/Waterfalls 6. Moorea - Christina & Gabriella Houses Accommodation Day 3 1. Moorea - Christina & Gabriella Houses Accommodation 2. Vrahakia Nature/Beaches 3. Koroni Castle Culture/Castles 4. Koroni Nature/Beaches WonderGreece.gr - Bon Voyage 1 Day 1 1. Moorea - Christina & Gabriella Houses Απόσταση: Start - Accommodation Χρόνος: - GPS: N36.960132529625945, W21.927522284130873 Note: Arriving at Petalidi, you will find the characteristic beauty of the Mediterranean coastal village with olive and fig trees giving a special charm. 2. Ancient Messini Απόσταση: by car 38.3km Culture / Archaelogical sites Χρόνος: 46′ GPS: N37.17531525140723, W21.920112358789083 Note: How an inhabitant lived in Ancient Messini? Where did he walk? Which buildings was looking on when was coming out of his house? These one will feel when visiting the ancient Messina. This really is a feeling, not a mere visual impression. 3. Archaeological Museum of Ancient Location: Ancient Messene (Mavromati) Messene Culture / Museums Contact: Τ: (+30) 27240 51201, 51046 Απόσταση: by car 1.0km Χρόνος: 10′ GPS: N37.18152235244687, W21.917387528419567 4. -

Publication of an Amendment Application Pursuant to Article 6(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 510/2006 on the Protection Of

C 186/18 EN Official Journal of the European Union 26.6.2012 Publication of an amendment application pursuant to Article 6(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 510/2006 on the protection of geographical indications and designations of origin for agricultural products and foodstuffs (2012/C 186/10) This publication confers the right to object to the amendment application pursuant to Article 7 of Council Regulation (EC) No 510/2006 ( 1). Statements of objection must reach the Commission within six months of the date of this publication. AMENDMENT APPLICATION COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 510/2006 AMENDMENT APPLICATION IN ACCORDANCE WITH ARTICLE 9 ‘ΚΑΛΑΜΑΤΑ’ (KALAMATA) EC No: EL-PDO-0117-0037-21.12.2009 PGI ( ) PDO ( X ) 1. Heading in the specification affected by the amendment: — Name of product — ☒ Description of product — ☒ Geographical area — Proof of origin — ☒ Method of production — ☒ Link — Labelling — National requirements — Other (please specify) 2. Type of amendment(s): — Amendment to single document or summary sheet — ☒ Amendment to specification of registered PDO or PGI for which neither the single document nor the summary sheet has been published — Amendment to specification that requires no amendment to the published single document (Article 9(3) of Regulation (EC) No 510/2006) — Temporary amendment to specification resulting from imposition of obligatory sanitary or phytosanitary measures by public authorities (Article 9(4) of Regulation (EC) No 510/2006) 3. Amendment(s): 3.1. Description of product: In this application the olive oil produced is described in greater detail than in the initial registration dossier. Stricter quality specifications are laid down in order to ensure that the name is used only for the area's very best quality olive oil. -

Notes and Inscriptions from South-Western Messenia Author(S): Marcus Niebuhr Tod Source: the Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol

Notes and Inscriptions from South-Western Messenia Author(s): Marcus Niebuhr Tod Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 25 (1905), pp. 32-55 Published by: The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/624207 . Accessed: 14/06/2014 14:24 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Hellenic Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 130.239.116.185 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 14:24:24 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions NOTES AND INSCRIPTIONS FROM SOUTH-WESTERN MESSENIA. I.-Introduction. THE following notes and inscriptions represent part of the results of a journey made in the spring of 1904, supplemented and revised on a second visit paid to the same district in the following November. One iuscription from Korone, a fragment of the 'Edictum Diocletiani,' I have already published (J.H.S. 1904, p. 195 foll.). I have attempted to state as briefly as possible the fresh topographical evidence collected on my tour, avoiding as far as possible any mere repetition of the descriptions and discussions of previous writers. -

Costamare Inc. Reports Results for the Fourth Quarter and Year Ended December 31, 2018

COSTAMARE INC. REPORTS RESULTS FOR THE FOURTH QUARTER AND YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2018 Monaco, January 23, 2019 – Costamare Inc. (“Costamare” or the “Company”) (NYSE: CMRE) today reported unaudited financial results for the fourth quarter and year ended December 31, 2018. • Adjusted Net Income available to common stockholders(1) of $ 13.3 million or $ 0.12 per share and $ 46.9 million or $ 0.42 per share for the three-months and the year ended December 31, 2018, respectively. • During 2018, ordered new buildings and acquired secondhand vessels for a total value of approximately $ 900.0 million. The TEU-weighted average employment period of the vessels involved in these transactions is 8 years. • Successfully concluded the acquisition of the 60% equity interest of York Capital Management in five 2016–built, 14,000 TEU containerships bringing the Company’s ownership in these five vessels to 100% (included in the above mentioned $ 900.0 million transactions). • Chartered in total 12 vessels over the quarter. • Declared dividend of $0.10 per share on its common stock and dividends on all four classes of its preferred stock. (1) Adjusted Net Income available to common stockholders is a non-GAAP measure and should not be used in isolation or as a substitute for Costamare’s financial results presented in accordance with U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (“GAAP”). For the definition and reconciliation of this measure to the most directly comparable financial measure calculated and presented in accordance with GAAP, please refer to Exhibit I. New Business Developments A. New acquisitions • In November 2018, we acquired the 60% equity interest of York Capital Management in five 2016– built, 14,000 TEU containerships. -

Excavation of a 13Th-Century Church Near Vasilitsi

hesperia yy (2008) EXCAVATION OF A Pages497S37 13TH-CENTURY CHURCH NEAR VASILITSI, SOUTHERN MESSENIA ABSTRACT A small-scaleexcavation in the area ofVasilitsi, southern Messenia, revealed the remnantsof a previouslyunrecorded 13th-centurytriple-aisled cross- vaulted churchwith a series of burials along its northwall. In addition to ceramicsand a marblebasin, a small hoard of Venetian torneselliwas found. The authordiscusses the church'speriod of use and details of its architecture and construction,as well as the identityof its builders and the settlement pattern of this largely unknown area. Parallels from published histories, surfacesurveys, and excavations fromother regions of medieval Messenia and Greece are discussed. An osteological reporton the burials is presented as an appendix. - In the past fewdecades, various regions of Messenia particularlytheir - Byzantine,Frankish, and Ottomanphases have attractedgreat interest amongarchaeologists, thereby providing a usefulbody of comparandafor currentwork in the area.1This report,which presents the results of exca- vationsin 2000 in southernMessenia, focuses on the remainsof a small 13th-centurychurch, probably built by a travelingguild of craftsmenfol- lowingLate Byzantineexamples in southernGreece. Architectural remains, alongwith skeletal, numismatic, and ceramicfinds, allow a glimpseof the dailylife of a smalllate medievalrural community.2 1. See,e.g., Nichoria III, pp. 353- tornesellihoard, while Stavroula Dou- Ephorateof Byzantine Antiquities, 434; Dimitrokallis1990; Hodgetts and bogianni,Thanos Katakos, and Giorgos Kalamata. Lock 1996;Davis et al. 1997;Davis Tsairiswere responsible for the con- LilianKarali examined burials 1-3 1998;Bennet, Davis, and Zarinebaf- servationof the finds. Marina Geor- in theLaboratory of Environmental Shahr2000; Davies2004; Zarinebaf, goutsouproduced the profile drawings Archaeology,Department of Archaeol- Bennet,and Davis 2005; see also ofthe ceramic vessels, and Giorgos ogyand Historyof Art, University of Sigalos2004, pp. -

Memory, Tradition, and Christianization of the Peloponnese,” by Rebecca J

AJA IMAGE GALLERY www.ajaonline.org Supplemental images for “Memory, Tradition, and Christianization of the Peloponnese,” by Rebecca J. Sweetman (AJA 119 [2015] 501–31). * Unless otherwise noted in the figure caption, images are by the author. Image Gallery figures are not edited by AJA to the same level as the published article’s figures. Fig. 1. Map of the Peloponnese, showing the location of the Late Antique churches (© 2014 Google Imagery Terrametrics). Key to Map: 13. Kato Roitika Other Basilicas in Arcadia 14. Leontion 27. Ay. Ioannis Achaea 15. Olena 28. Astros 29. Astros Villa Loukou Patras 16. Patras Vlachou 30. Chotousa 1. Patras Botsi Street 17. Platanovrysi 31. Gortys 2. Patras Harado 18. Skioessa 32. Kato Doliana 3. Patras Kanakari Street 124-6 19. Tritaia 33. Kato Meligous Kastraki 4. Patras Kanakari Street 46-52 34. Kato Meligous, Ay. Georgios 5. Patras Korinthos Street Arcadia 35. Lykosoura 6. Patras Midilogli Tegea 36. Mantinea City and Theater 7. Patras Rofou 20. Pallantion 1 Christoforo 37. Megalopolis, East of Theater 8. Patras Terpsithea 21. Pallantion, Ay. Giorgou 38. Orchomenos 9. Patras Zarouchleika 22. Tegea Agora 39. Phalaisai (Lianou) 10. Patras, Ay. Andreas 23. Tegea Agora Thyrsos 40. Thelpoussa Other Basilicas in Achaia 24. Tegea Provantinou 11. Aighion 25. Tegea Temple Alea Continued on next page. 12. Kato Achaia 26. Tegea Theater Published online October 2015 American Journal of Archaeology 119.4 1 DOI: 10.3764/ajaonline1194.Sweetman.suppl AJA IMAGE GALLERY www.ajaonline.org Key to Map (continued). Argolid Nemea Kainepolis-Kyparissos 86. Nemea 126. Kainepolis-Kyparissos Monastiri Ano Epidauros 127. -

Petalidi - Chrani - Agios Andreas - Koroni Kalamata & Rizomilos Ancient Messine

Petalidi - Chrani - Agios Andreas - Koroni Kalamata & Rizomilos Ancient Messine Pylos Polimnio Petalidi the Messinian Kalamaki Riviera Vigla Chrani The east coast of the western peninsula of Messinia, from Petalidi to Koroni, has a great deal to offer visiting tourists. The fertile coastline has a number of fine, sandy beaches Agios Andreas Loga and each village en route very much has its own char- acter, from the impressive central square of Petalidi to the narrow, winding streets of Koroni. It is an area Neo Koroni that could be described as “old Greece” as, unlike in other parts of Messinia, there has not been large scale development. Instead, there is a good variety Vounaria of small scale accommodations to choose from and Harokopio even in the height of summer the beaches do not Agios Triada get too crowded. Accessing the area could not be easier- the first resort of Petalidi is less than a half Koroni hour drive from Kalamata airport. Zaga Petalidi Petalidi Heading south from Rizomilos the first asphalt road to the left takes you down to the beach at Petalidi Bay, which can also be approached through the campsite a little bit further south. This takes you on through Kalohori, before joining the main Pylos beach is a pretty stretch of sand looking over towards Kalamata. road. On the way you will pass fields of vines, mainly grown for To the south of the beach is Petalidi Beach Camping. Between currants here, and other fruit crops in abundance. The road up the campsite and the town of Petalidi is a deserted strip of sand, to Kastania is another worthwhile route up into the hills above reached by taking the turning just to the north of a petrol station Petalidi. -

Messinia Coastal Biking Tour

MESSINIA COASTAL BIKING TOUR COUNTRY: Greece LOCATION: Messinia–South Peloponnese DEPARTURES: 2018, every Saturday from April to October. DURATION: 8 days PRICE: €750p.p (+€60 on high season May 14th- June 18th, August 27th- October 15th) excluding flights, for double, triple, quad room or apartment. ACCOMMODATION: 3* hotel or apartments (depending on availability) ADDITIONAL CHARGES: Single supplement €140 Bike rental: Trekking bike 80€/week, Road bike 120€/week, E-bike 220€/week, Tandem bike 240€/week. TRANSPORTATION FROM/TO ATHENS AIRPORT*: 1. Transfer by public Bus (National Transportation) 2. Direct transfer by us: Athens airport-Kalamata 240€ (up to 4 persons). Kalo Nero-Athens 240€ (up to 4 persons). Kalamata airport – Kalamata 20€ ( up to 4 persons). Kalo Nero- Kalamata airport 120€ (up to 4 persons). 3. Bike transfer €10 (one way). About this holiday If you are looking for a biking holiday that includes extraordinary beaches with incomparable blue waters, soft weather, summertime relaxation and all these combined with culture and beautiful landscapes, then you just found it! Your destination is Messinia, in the south-west part of Peloponnese, one of the most beautiful parts of Greece! You will take an 8-day tour along the coast beginning from Kalamata, the famous seaside capital of Messinia. Riding among the beautiful settlemets, well known for their great medieval Castles like Methoni, Koroni and Pylos, you will end up in Kalo Nero on the west coast. The route is easy enough and you don’t have to be extremely fit to make it. In addition, you will have plenty of opportunities to make a stop and admire the Greek nature, try the local food and drinks or take a deep experience about Greece and the Greek way of living in the blessed Messinian land! Self-guided tour During this trip, you will cycle on your own without the presence of a guide. -

MONTAZ 04 PATRA.Cdr

DISTOS Arma PlakaDilessi Mazi Eleonas Ag. Kiriaki a J AgiaTriada AONIONFIELD 9,5 Dilessi Pigadaki Halkoutsi Kon/nos N.EVOIKOSKOLPOS 1549 Evangelistria 2,5 2 Shimatari 2,5 5 Argiro 3 q Panagia Skala NeaPalatia p Stenos KOLPOS THESPIES 4,5 7,5 3 2 2 5,5 3 Mpoufalo 3 2 N.Kalidona Psathopirgos Ag.Nikolaos Tarsos 3,5 c Inoi 6,5 Kamari Oropú Paralia ep KianiAkti Akr.Andromahi Akr.Mounta 3 c bce Tanagra 3,5 Par.Zarakon SHINIAS 1,5 q ANTIKIRAS Mavromati 2,5 8 2,5 1,5 Zarakes Akr.Antirio K.Arahovitika 2,5 6,5 Kalithea TANAGRA EVIA 5 Tourlida q 32 Ag.Athanassios 1561 1526 Askri 3,5 3,5 5,5 Vagia 1,5THIVA 3,5 Sessas 5 9 5 5 Antirio 3,5 2 KatoRodini 8,5 MakriaMalia AgiaAna 1,5 2,5 Ag.Apostoli AG.SOSTIS Arahovitika (Askrea) 2 1 5,5 Inofita Sikamino 4 Ag.Dimitrios 3 q TSAROUHI 2,5 Thespies Tahi 2,5 Markopoulo ParaliaKalamou 3,5 OXIA 27 Ag.Andreas Makariotissasmon. Leontari 6 9 6,5 Oropos 3 Kalamos THOLI PROKOPANISTOS 3 Drepano Lambiri Neohori 2,5 Ambelohori Almiropotamos pRio Ag.Vassilios Rodini Ziria Pefka 1748 a 7 Asopia 5,5 1,5 J 2 Bouka AMBELOS Panagia 14 3 Neohoraki c3,5 Panagia 4 Akr.Evinos qe 2 2 2 Ag.Nikolaos Lutúfi 5 11 Milessi Ieo Messohoria Platani AnoZiria DASKALIO a Domvousmon. 4,5 Å962 Ag.Thomas 5,5 1 Asprohori AMFIARAION 4 8 Kamares Longos Kalamiotissa Klidi 22 79 Livissi Ag.Dimitrios 1,5 5 Argira Akr.Makrinikolas Akr.Ag.Pangalos 6 9 3 Ag.Nektariosmon. -

Messinia Guide EG

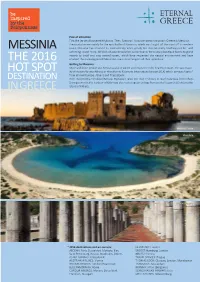

Pole of attraction First the jet-set discovered Mykonos. Then, Santorini. Now the latest hot spot in Greece is Messinia. Previously known mainly for the epic Battle of Navarino, which was fought off the coast off its western MESSINIA coast, Messinia has retained its local identity while gently but inspirationally reaching out for - and achieving - much more. All kinds of accommodation can be found, from luxury boutique hotels to grand resorts to small and cozy rented rooms, which have respected the natural environment and have THE 2016 enabled the once-neglected Messinian coasts to emerge in all their splendour. Getting to Messinia More and more people visit Messinia also in winter and enjoy the mild, healthy climate. The vast major- HOT SPOT ity of visitors fly into Athens or directly into Kalamata International airport (KLX) which services flights* from all over Europe, Athens and Thessaloniki. DESTINATION With the recently completed Moreas Highway it takes less than 2,5 hours to reach Kalamata from Athens. During summer, the harbour of Kalamata also hosts regular sailings from and to Kissamos (Crete) via the IN GREECE island of Kithyra. Methoni Castle Voidokilia Ancient Messini * 2014 destinations and air carriers: GERMANIA: London AEGEAN: Paris, Dusseldorf, Moscow, Kiev, EASYJET: Hamburg, London Saint Petersburg, Rostov, Stockholm, Athens NIKI FLY: Vienna ASTRA AIRLINES: Thessaloniki TRAVEL SERVICE: Prague AUSTRIAN AIRLINES: Vienna THOMAS COOK: Glascow, London, Manchester BRITISH AIRWAYS: London (Heathrow) TRANSAVIA: Amsterdam BLUE PANORAMA: -

A Bibliography on the History and Archaeology of Ancient Messene1 Ancient Messene Project

A Bibliography on the History and Archaeology of ancient Messene1 Ancient Messene Project Version 14.05.2020 This bibliography is a regularly updated work-in-progress. For any additions, corrections and suggestions, please mail to: [email protected] 1831 – 1838 Blouet, A., Expédition scientifique de Morée, ordonnée par le gouvernement français. Architecture, sculptures, inscriptions, et vues du Péloponnèse, des Cyclades et de l’Attique (Expédition scientifique de Morée), Ι – ΙΙΙ, Paris 1831, 27 – 33, tab. 22 – 47. (=Abel Blouet, Επιστημονική Αποστολή του Μορέως: Φωτοανατύπωση του κεφαλαίου περί Μεσσήνης, Athens 1997) 1844 Le Βas, Ph., Fouilles à Messène, Revue Archéologiques 1 (1844), 422 – 426. 1876 Stamatakis, P., ΠΑΕ 1876, 27-28. 1879 Oikonomakis, St., Tά σωζόμενα Iθώμης, Mεσσήνης καί τα πέριξ, Kalamata 1879. Petridis, Ath., Περί Iθώμης καί Mεσσήνης, Παρνασσός 3 (1879), 1018-1026. 1880 Petridis, Ath., Eπιγραφαί Mεσσήνης, Παρνασσός 4 (1880), 497- 498. 1888 Le Bas, Ph., Temple de Diane Laphria à Messène, in: Reinach, S., Voyage archéologique en Grèce et en Asie mineure sous la direction de M. Philippe Le Bas membre de l’Institut (1842-1844), Paris 1888, 134-138. 1 This bibliographical list was compiled and is regularly updated by Nikos Tsivikis initially based on older versions by Petros Themelis and other scholars working on Messene. 1 1891 Wilhelm, A., Inschriften aus Messene, AM 16 (1891), 345-355. 1895 Sofoulis, Th., Ανασκαφή Αρχαίας Μεσσήνης, ΠΑΕ (1895), 27-28. Sofoulis, Th., Ανασκαφή Αρχαίας Μεσσήνης, ΑΜ 20 (1895), 375. 1896 Sofoulis, Th., Ανασκαφή Αρχαίας Μεσσήνης, ΑΑ 11 (1896), 73. 1904 Kolbe, W., Die Grenzen Messeniens in der ersten Kaisezeit, AM 29 (1904), 364-378. -

705 Glossary

INDEXRUNNING HEAD VERSO PAGES 715 Sights and monuments in larger cities (Athens and Thessaloniki) are listed as sub- indices of that city. For the Parthenon, for example, look under ‘Athens: Parthenon’. In general, explanatory or more detailed references (where there are many) are given in bold. Numbers in italics are picture references. Dates are given for all artists, archi- tects and sculptors. Ancient place names and works of art are listed in italics. The stressed syllables of modern place names are indicated. A Ag. Andrèas (Pàtras) 404 Abdera 688–90; (finds from) 662, 693 Ag. Apòstoloi (Kastorià) 641 Abdul Hamid, sultan 596 Ag. Apòstoloi (Leondàri) 277 Acarnanìa 485, 488, 500 Ag. Apòstoloi (Seliàna) 408 Acciaioli, Franco 64 Ag. Athanàsios (Chalandrìtsa) 414 Achaea, Roman province 19, 154, 300, 399 Ag. Athanàsios (Geràki) 319 Achaea, region (see Achaia) Ag. Athanàsios (Kastorià) 641 Achaeans 154, 204, 271, 485 Ag. Athanàsios (Leondàri) 277 Achaean League 18, 274, 400, 405, 407 Ag. Charalàmbos (Kalamàta) 343 Achaìa 399ff Ag. Charalàmbos (Maròneia) 695 Achaia Clauss winery 404–05 Ag. Dimìtrios (Chr`ysafa) 317 Achelòös, river 488, 540, 542 Ag. Dimìtrios (Mistrà) 312 Achèrondas, river (Acheron) 527, 528, 529 Ag. Dimìtrios Katsoùri (Plisioì) 506 Achilles 536, 563, 564 Ag. Dion`ysios (Olympus) 580 Achladòkambos 254 Ag. Geòrgios (Androùsa) 344 Acrocorinth 178–80, 179 Ag. Geòrgios (Nàfplion) 235 Actium, battle of 19, 485, 499–500 Ag. Geòrgios (Sithonìa) 681 Adrastus of Argos 190, 222, 419 Ag. Geòrgios (Stemnìtsa) 282 Adrianople (see Adrianoupolis) Ag. Geòrgios (village in Thessaly) 576 Adrianoùpolis 41, 47, 702 Ag. Geòrgios (Vasilikò, Epirus) 526 Aegeiai, site of 325 Ag.