"Coral" Islands: Data from the Bahamas and Oceania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Soils of Niue Island, South Pacific

Geochemical Journal, Vol. 24, pp. 371 to 378, 1990 Anomalous Hg contents in soils of Niue Island, South Pacific NEIL E. WHITEHEAD', JOHN BARRIE2 and PETER RANKIN3 Nuclear Sciences Group, Division of Physical Sciences, D.S.I.R. P.O.Box 31-312, Lower Hutt, New Zealand', Avian Mining Ltd., 24 Jindvik Place, Canberra, A.C.T., Australia2 and Division of Land and Soil Sciences, D.S.I.R., Private Bag, Taita, New Zealand3 (Received September 10, 1990; Accepted December 29, 1990) Niue Island, a raised coralline atoll in the South Pacific, has soils that have long been known to have strongly anomalous radioactivity. We now show that there is also a highly anomalous Hg content in the soils. It is associated with the radioactivity and the goethite/gibbsite content and the values are as high as those in soils over known Hg-mineralisation in volcanic settings, though no mineralisation is known on Niue and such an occurrence on this coral island would be geochemically unusual. INTRODUCTION GEOLOGY AND SOILS OF NIUE ISLAND Niue Island in the South Pacific is a raised A detailed description of the geological set coral atoll, located at 19° S and 169° W. The in ting of Niue Is. may be found in Schofield (1959) terior of the island is dolomitised, and is covered and a summary follows. by reddish-brown soils rich in Fe, Al and Niue Island is a raised coral atoll consisting phosphate in the form of goethite, gibbsite and of seaward cliffs rising steeply from the sea but crandallite respectively (the mean soil P205 is girded by a terrace on which sits Alofi, the 4%; Whitehead et al. -

Challenges in Freshwater Management in Low Coral Atolls

Journal of Cleaner Production 15 (2007) 1522e1528 www.elsevier.com/locate/jclepro Challenges in freshwater management in low coral atolls Ian White a,*, Tony Falkland b, Pascal Perez c, Anne Dray c, Taboia Metutera d, Eita Metai e, Marc Overmars f a Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies, Institute of Advanced Studies, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia b Ecowise Environmental, ACTEW Corporation, PO Box 1834, Fyshwick ACT 2609, Australia c CIRAD Montpellier France and Resource Management in the Asia-Pacific Program, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Institute of Advanced Studies, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia d Public Utilities Board, Betio, Tarawa, Republic of Kiribati e Water Engineering Unit, Public Works Department, Betio, Tarawa, Republic of Kiribati f South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission, Suva, Fiji Received 13 January 2005; accepted 31 July 2006 Available online 13 October 2006 Abstract Population centres in low atoll islands have water supply problems that are amongst the most critical in the world. Fresh groundwater, the major source of water in many atolls, is extremely vulnerable to natural processes and human activities. Storm surges and over-extractions cause seawater intrusion, while human settlements and agriculture can pollute shallow groundwaters. Limited land areas restrict freshwater quantities, particularly in frequent ENSO-related droughts. Demand for freshwater is increasing and availability is extremely limited. At the core of many groundwater management problems are the traditional water ownership rights inherent in land tenure and the conflict between the requirements of urbanised societies and the traditional values and rights of subsistence communities living on groundwater reserves. -

Evaporation Rates for a Coral Island by Field Observation and Simulation

23rd International Congress on Modelling and Simulation, Canberra, ACT, Australia, 1 to 6 December 2019 mssanz.org.au/modsim2019 Evaporation rates for a coral island by field observation and simulation S. Han ab, S. Liu bc, S. Hu b, X. Mo bc and X. Song bc a University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, PR China, b Key Laboratory of Water Cycle and Related Land Surface Processes, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, PR China, c College of Resources and Environment, Sino- Danish Center, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, PR China. Email: [email protected] Abstract: Evaporation in coral islands influences their limited freshwater recharge and plays an important role in coral reefs ecology protection under the background of climate changes. From June 20th to August 16th, 2018, a field experiment was carried out in Zhaoshu Island, Xisha Islands, China, using a self-made micro- lysimeter and pan evaporation dish. To understand the whole process of evaporations at the annual scale, we used the Penman-Monteith model and crop coefficient (Kc) method to estimate potential evaporation (ETo) and actual evaporation (ETc) using meteorological data and leaf area index (LAI). The results show (1) ETo reached its peak value earlier than precipitation, causing island vegetations to suffer the highest water stress at the end of the dry season. (2) in the wet season, ETc rose as the precipitation increased, however, the ETo presented a tendency of slowly declining. These phenomena indicate that the vegetation could suffer from strong drought at the end of the dry season because of the maximum ETo and extended low rate of precipitation. -

Global Climate Change and Coral Reefs: Implications for People and Reefs

Global Climate Change and Coral Reefs: Implications for People and Reefs Report of the UN EP-IOC-ASPEI-UCN Global Task Team on the Implications of Climate Change on Coral Reefs — THE AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF MARINE SCIENCE Established in 1972, the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) is a federally funded statutory authority governed by a Council appointed by the Australian government. The Institute has established a high national and international reputation in marine science and technology, principally associated with an understanding of marine communities of tropical Australia, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific and Indian Oceans. The Institute’s long-term research into complex marine ecosystems and the impacts of human activities on the marine environment is used by industry and natural resource management agencies to ensure the conservation and sustainable use of marine resources in these regions. KANSAS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The Kansas Geological Survey is a research and service organisation operated by the University of Kansas. The Survey’s mission is to undertake both fundamental and applied research in areas related to geologic resources and hazards, and to disseminate the results of that research to the public, policy-makers and the scientific community. THE MARINE AND COASTAL AREAS PROGRAMME IUCN’S Marine and Coastal Areas Programme was established in 1985 to promote activities which demonstrate how conservation and development can reinforce each other in marine and coastal environments; conserve marine and coastal species and ecosystems; enhance aware- ness of marine and coastal conservation issues and management; and mobilise the global conservation community to work for marine and coastal conservation. -

OC-002 VK9 Christmas Island OC-003 VK9 Cocos (Keeling)

Oceania Written by Administrator Sunday, 19 February 2012 23:55 - Last Updated Monday, 20 February 2012 00:37 OC-001 VK Australia (Main Island Only) OC-002 VK9 Christmas Island OC-003 VK9 Cocos (Keeling) Islands OC-004 VK9 Lord Howe Island OC-005 VK9 Norfolk Island OC-006 VK7 Tasmania (Main Island Only) OC-007 VK9 Willis Islands OC-008 P2 Bismarck Archipelago OC-009 T8 Palau Islands OC-010 V63 Pohnpei Islands OC-011 V63 Chuuk Islands OC-012 V63 Yap Islands OC-013 ZK1 Rarotonga Island OC-014 ZK1 Manihiki Atoll OC-015 T2 Tuvalu Islands OC-016 3D2 Viti Levu & Vanua Levu Group OC-017 T30 Gilbert Islands OC-018 T30 Banaba (Ocean) Island OC-019 KH6,7 Hawaiian Islands OC-020 KH7K Kure Atoll OC-021 YB0-3 Java (Jawa) Island (Main Island Only) OC-022 YB9 Bali Island OC-023 KH3 Johnston Atoll OC-024 T32 Kiritimati (Christmas) Island OC-025 P2 Admiralty Islands OC-026 KH2 Guam Island OC-027 FO Marquesas Islands OC-028 V73 Ralik Chain OC-029 V73 Ratak Chain OC-030 KH4 Midway Islands OC-031 C2 Nauru OC-032 FK New Caledonia Island OC-033 FK Loyalty Islands OC-034 P2,YB9 New Guinea (Main Island Only) OC-035 YJ New Hebrides OC-036 ZL1,2 North Island (Main Island Only) OC-037 ZL9 Campbell Island OC-038 ZL7 Chatham Islands OC-039 ZL8 Kermadec Islands OC-040 ZK2 Niue Island OC-041 P2 Ninigo Group OC-042 DU1-4 Luzon Island (Main Island Only) OC-043 T31 Phoenix Islands OC-044 VP6 Pitcairn Island OC-045 KH8 Tutuila Island OC-046 FO Windward Islands 1 / 6 Oceania Written by Administrator Sunday, 19 February 2012 23:55 - Last Updated Monday, 20 February 2012 00:37 -

Pacific Ocean Coral Island Reveals How Human Settlement Affects Water Quality 17 February 2014, by Niall Byrne

Pacific Ocean coral island reveals how human settlement affects water quality 17 February 2014, by Niall Byrne sites close to and far from human populations and fishing. They found that greater levels of fishing were associated with bigger differences in dead and live shell types. "At more heavily fished sites, the living population was dominated by foraminifera that thrive in high- nutrient conditions," Jessica says. The relationship suggests that fishing can lead to higher nutrients in the water column, which is generally bad for corals, supporting other research that shows healthy fish populations are important for healthy coral reefs. Kirimati Island was settled in the 1970s when a re- population program in the Republic of Kiribati moved people from the overcrowded capital, Tarawa, to under-populated outer islands. Provided by ANSTO A Pacific Ocean coral island, populated around 40 years ago, reveals how human settlement can quickly degrade water quality and affect the health of coral reefs, Sydney scientists say. Jessica Carilli, of the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation, and Sheila Walsh, of the Nature Conservancy, used Kirimati Island to examine the shells made by an organism that thrives in high-nutrient conditions, which is considered detrimental to coral. "We used a unique metric to estimate water quality before and after people arrive by comparing types of dead and live microscopic shells in reef sand made by organisms called foraminifera," says Jessica, an ANSTO postdoctoral fellow. Jessica and Shelia collected sand underwater at 1 / 2 APA citation: Pacific Ocean coral island reveals how human settlement affects water quality (2014, February 17) retrieved 29 September 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2014-02-pacific-ocean-coral- island-reveals.html This document is subject to copyright. -

Niue Integrated Strategic Plan – 2003 - 2008

HHaallaavvaakkaa kkee hhee MMoonnuuiinnaa Governance Financial Stability Social Economic Environment Development Niue Integrated Strategic Plan – 2003 - 2008 Niue Ke Monuina – A Prosperous Niue COUNTRY PROFILE Geography Niue is a single coral island of 259 square kilometers in the South Pacific Ocean at latitude 19 south and longitude 169 west. Niue has an Exclusive Economic Zone of 293,988 sq km. It is the largest raised coral island in the world and is known for its unspoilt environment and pristine coastal waters. People, culture and tradition Niueans are of Polynesian descent and are said to be amongst the friendliest people in the world. They speak Niuean, which has close links to other Polynesian languages. Culture, tradition, spirituality and social values play an integral part in the unique Niuean culture. Population In March 2002 the population was 1707. This compares with 20,145 residents of New Zealand who claimed to be of Niuean descent in the 2001 Census. The declining population has created difficulties in maintaining adequate public services but more importantly threatens the existence of Niue’s cultural heritage and sovereignty. The Government Since 1974 Niue has been self-governing in free association with New Zealand. Under this constitutional arrangement New Zealand is responsible for defense and external affairs as well as providing necessary economic and administrative assistance. General elections are held once every three years for the 20 members of the Legislative Assembly. Since 2001 Niue has full diplomatic representation in New Zealand. Economy In 2002 GDP was $14.2m, which equates to $7,470 per capita. The Government is the major employer in Niue. -

Law of Thesea

Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea Office of Legal Affairs Law of the Sea Bulletin No. 82 asdf United Nations New York, 2014 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Furthermore, publication in the Bulletin of information concerning developments relating to the law of the sea emanating from actions and decisions taken by States does not imply recognition by the United Nations of the validity of the actions and decisions in question. IF ANY MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THE BULLETIN IS REPRODUCED IN PART OR IN WHOLE, DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT SHOULD BE GIVEN. Copyright © United Nations, 2013 Page I. UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON THE LAW OF THE SEA ......................................................... 1 Status of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, of the Agreement relating to the Implementation of Part XI of the Convention and of the Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the Convention relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks ................................................................................................................ 1 1. Table recapitulating the status of the Convention and of the related Agreements, as at 31 July 2013 ........................................................................................................................... 1 2. Chronological lists of ratifications of, accessions and successions to the Convention and the related Agreements, as at 31 July 2013 .......................................................................................... 9 a. The Convention ....................................................................................................................... 9 b. -

Cultural Landscapes of the Pacific Islands Anita Smith 17

Contents Part 1: Foreword Susan Denyer 3 Part 2: Context for the Thematic Study Anita Smith 5 - Purpose of the thematic study 5 - Background to the thematic study 6 - ICOMOS 2005 “Filling the Gaps - An Action Plan for the Future” 10 - Pacific Island Cultural Landscapes: making use of this study 13 Part 3: Thematic Essay: The Cultural Landscapes of the Pacific Islands Anita Smith 17 The Pacific Islands: a Geo-Cultural Region 17 - The environments and sub-regions of the Pacific 18 - Colonization of the Pacific Islands and the development of Pacific Island societies 22 - European contact, the colonial era and decolonisation 25 - The “transported landscapes” of the Pacific 28 - Principle factors contributing to the diversity of cultural Landscapes in the Pacific Islands 30 Organically Evolved Cultural Landscapes of the Pacific 31 - Pacific systems of horticulture – continuing cultural landscapes 32 - Change through time in horticultural systems - relict horticultural and agricultural cultural landscapes 37 - Arboriculture in the Pacific Islands 40 - Land tenure and settlement patterns 40 - Social systems and village structures 45 - Social, ceremonial and burial places 47 - Relict landscapes of war in the Pacific Islands 51 - Organically evolved cultural landscapes in the Pacific Islands: in conclusion 54 Cultural Landscapes of the Colonial Era 54 Associative Cultural Landscapes and Seascapes 57 - Storied landscapes and seascapes 58 - Traditional knowledge: associations with the land and sea 60 1 Part 4: Cultural Landscape Portfolio Kevin L. Jones 63 Part 5: The Way Forward Susan Denyer, Kevin L. Jones and Anita Smith 117 - Findings of the study 117 - Protection, conservation and management 119 - Recording and documentation 121 - Recommendations for future work 121 Annexes Annex I - References 123 Annex II - Illustrations 131 2 PART 1: Foreword Cultural landscapes have the capacity to be read as living records of the way societies have interacted with their environment over time. -

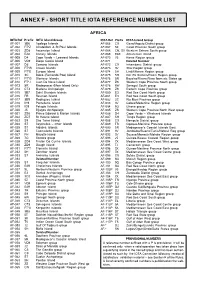

Short Title Iota Reference Number List

RSGB IOTA DIRECTORY ANNEX F - SHORT TITLE IOTA REFERENCE NUMBER LIST AFRICA IOTA Ref Prefix IOTA Island Group IOTA Ref Prefix IOTA Island Group AF-001 3B6 Agalega Islands AF-066 C9 Gaza/Maputo District group AF-002 FT*Z Amsterdam & St Paul Islands AF-067 5Z Coast Province South group AF-003 ZD8 Ascension Island AF-068 CN, S0 Western Sahara South group AF-004 EA8 Canary Islands AF-069 EA9 Alhucemas Island AF-005 D4 Cape Verde – Leeward Islands AF-070 V5 Karas Region group AF-006 VQ9 Diego Garcia Island AF-071 Deleted Number AF-007 D6 Comoro Islands AF-072 C9 Inhambane District group AF-008 FT*W Crozet Islands AF-073 3V Sfax Region group AF-009 FT*E Europa Island AF-074 5H Lindi/Mtwara Region group AF-010 3C Bioco (Fernando Poo) Island AF-075 5H Dar Es Salaam/Pwani Region group AF-011 FT*G Glorioso Islands AF-076 5N Bayelsa/Rivers/Akwa Ibom etc States gp AF-012 FT*J Juan De Nova Island AF-077 ZS Western Cape Province South group AF-013 5R Madagascar (Main Island Only) AF-078 6W Senegal South group AF-014 CT3 Madeira Archipelago AF-079 ZS Eastern Cape Province group AF-015 3B7 Saint Brandon Islands AF-080 E3 Red Sea Coast North group AF-016 FR Reunion Island AF-081 E3 Red Sea Coast South group AF-017 3B9 Rodrigues Island AF-082 3C Rio Muni Province group AF-018 IH9 Pantelleria Island AF-083 3V Gabes/Medenine Region group AF-019 IG9 Pelagie Islands AF-084 9G Ghana group AF-020 J5 Bijagos Archipelago AF-085 ZS Western Cape Province North West group AF-021 ZS8 Prince Edward & Marion Islands AF-086 D4 Cape Verde – Windward Islands AF-022 ZD7 -

The Silent Cannon of Takapoto

Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation Volume 8 Article 6 Issue 4 Rapa Nui Journal 8#4, December 1994 1994 The iS lent Cannon of Takapoto Leendart Roggeveen Follow this and additional works at: https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/rnj Part of the History of the Pacific slI ands Commons, and the Pacific slI ands Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Roggeveen, Leendart (1994) "The iS lent Cannon of Takapoto," Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation: Vol. 8 : Iss. 4 , Article 6. Available at: https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/rnj/vol8/iss4/6 This Research Report is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Hawai`i Press at Kahualike. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rapa Nui Journal: Journal of the Easter Island Foundation by an authorized editor of Kahualike. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Roggeveen: The Silent Cannon of Takapoto The Silent Cannon ofTakapoto Leendert Roggeveen The Netherlands In RNJ 8:79-80 I related Gerard Boon's story about the of the visit of the tall ships of Schouten and LeMaire that cannon found on the island Takapoto in the Tuamotus which could not anchor here. Whatever they may have left behind, could conceivably be cannon from the Africaensche Galey. they certainly did not miss any of their cannon when they The Africaensche Galey was the smallest of the three sailed on. ships with which Jacob Roggeveen set out on his voyage in Poort continues his story with the description 'Of the search of the unknown Southland. -

Atoll Research Bulletin No* 277 Takapoto Atoll, Tuamotu Archipelago

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO* 277 TAKAPOTO ATOLL, TUAMOTU ARCHIPELAGO: TERRESTRIAL VEGETATION AND FLORA BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON, DOC., U.S.A. DECEMBER 1983 ~akatopatere Airstrip village Fig. 1. Takapoto Atoll TAKAPOTO ATOLL, TUAMOTU ARCHIPELAGO: TERRESTRIAL VEGETATION AND FLORA INTRODUCTION The Man and the Biosphere (MAB) programme of UNESCO, first thought of in 1968, launched in 1970 and endorsed by the Stockholm Conference of 1972, includes a number of scientific projects, of which No. 7 is de- voted to the Ecology and Rational Utilization of Island Ecosystems. All the programmes are to be interdisciplinary and intergovernmental. Among member countries which developed their own national plans within the framework of the separate MAB projects, France drafted a vigorous one in MAB 7 in French Polynesia, under the leadership of Dr. B. Salvat (1977). The French programme includes a detailed study of an atoll, Takapoto in the Tuamotus, and comparison of its ecosystems and their functioning with those of a high island already under scrutiny, Moorea in the Society Islands. Teams of over 40 scientists representing many disciplines visited Takapoto over a period of several years (1974-1976). Several research organisations participated, in some cases bending their own study goals to fit the MAB-7 framework, so that an extensive body of information has become available and lends itself to integration and synthesis. Pre- liminary reports, as well as some final papers have been published. I was already in SE Polynesia in 1974-75 and it was arranged that I would visit Takapoto in Dec. 1974 to study its flora and vegetation.