A Quarterly of Women's Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dragon Magazine Within the Last Cherie Knull Tually Has Been with Us Since Last October, Year

January 1981 Dragon 1 Dragon Vol. V, No. 7 Vol. V, No. 7 January 1981 Publisher. E. Gary Gygax Editor. Jake Jaquet Assistant editor. Kim Mohan Good-bye 1980, hello 1981. And hello to a tain aspects of role-playing and the benefits Editorial staff . Bryce Knorr couple of new (and pretty, I might add, if I derived therefrom. He and his wife, who is Marilyn Mays won’t get accused of sexism) faces here at the typist and a behind-the-scenes collab- Sales & Circulation . Debbie Chiusano Dragon Publishing. New, or at least rela- orator, have been responsible for more Corey Koebernick tively new, to our sales and circulation de- than a dozen short articles and stories pub- Office staff . Dawn Pekul partment is Debbie Chiusano—Debbie ac- lished in Dragon magazine within the last Cherie Knull tually has been with us since last October, year. Roger’s name is on the alchemist and Roger Raupp but this has been our first opportunity to astrologer NPC articles in this issue, and in Contributing editors . Roger Moore formally welcome her in print. The most Dragon issue #44 he became the first Ed Greenwood recent addition to our organization is author to have two creatures featured in Marilyn Mays, added just last month to our Dragon’s Bestiary in the same magazine. editorial staff. Let’s hear it for the new kids This month’s contributing artists: on the block! With the start of a new year, it seems appro- Morrissey Jeff Lanners priate to reflect a bit on the past year and Roger Raupp Kenneth Rahman We’re also happy to welcome two other look ahead a little to the future. -

The Ethics of Intelligence Collection Ross W. Bellaby

What’s the Harm? The Ethics of Intelligence Collection Ross W. Bellaby Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of International Politics Aberystwyth University June 13th, 2011 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed ...................................................................... (Ross W. Bellaby) Date ........................................................................ STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where *correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote(s). Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed ..................................................................... (Ross W. Bellaby) Date ........................................................................ [*this refers to the extent to which the text has been corrected by others] STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ..................................................................... (Ross W. Bellaby) Date ........................................................................ I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying -

Darpa Starts Sleuthing out Disloyal Troops

UNCLASSIFIED (U) FBI Tampa Division CI Strategic Partnership Newsletter JANUARY 2012 (U) Administrative Note: This product reflects the views of the FBI- Tampa Division and has not been vetted by FBI Headquarters. (U) Handling notice: Although UNCLASSIFIED, this information is property of the FBI and may be distributed only to members of organizations receiving this bulletin, or to cleared defense contractors. Precautions should be taken to ensure this information is stored and/or destroyed in a manner that precludes unauthorized access. 10 JAN 2012 (U) The FBI Tampa Division Counterintelligence Strategic Partnership Newsletter provides a summary of previously reported US government press releases, publications, and news articles from wire services and news organizations relating to counterintelligence, cyber and terrorism threats. The information in this bulletin represents the views and opinions of the cited sources for each article, and the analyst comment is intended only to highlight items of interest to organizations in Florida. This bulletin is provided solely to inform our Domain partners of news items of interest, and does not represent FBI information. In the JANUARY 2012 Issue: Article Title Page NATIONAL SECURITY THREAT NEWS FROM GOVERNMENT AGENCIES: American Jihadist Terrorism: Combating a Complex Threat p. 2 Authorities Uncover Increasing Number of United States-Based Terror Plots p. 3 Chinese Counterfeit COTS Create Chaos For The DoD p. 4 DHS Releases Cyber Strategy Framework p. 6 COUNTERINTELLIGENCE/ECONOMIC ESPIONAGE THREAT ITEMS FROM THE PRESS: United States Homes In on China Spying p. 6 Opinion: China‟s Spies Are Catching Up p. 8 Canadian Politician‟s Chinese Crush Likely „Sexpionage,‟ Former Spies Say p. -

Covert Networks a Comparative Study Of

COVERT NETWORKS A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF INTELLIGENCE TECHNIQUES USED BY FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE AGENCIES TO WEAPONIZE SOCIAL MEDIA by Sarah Ogar A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Baltimore, Maryland December 2019 2019 Sarah Ogar All Rights Reserved Abstract From the Bolshevik Revolution to the Brexit Vote, the covert world of intelligence has attempted to influence global events with varying degrees of success. In 2016, one of the most brazen manifestations of Russian intelligence operations was directed against millions of Americans when they voted to elect a new president. Although this was not the first time that Russia attempted to influence an American presidential election, it was undoubtedly the largest attempt in terms of its scope and the most publicized to date. Although much discussion has followed the 2016 election, there have not been much concerted historical analysis which situates the events of 2016 within the global timeline of foreign intelligence collection. This paper argues that the onset of social media has altered intelligence collection in terms of its form, but not in terms of its essence. Using the case study method, this paper illustrates how three different nations apply classical intelligence techniques to the modern environment of social media. This paper examines how China has utilized classical agent recruitment techniques through sites like LinkedIn, how Iran has used classical honey trap techniques through a combination of social media sites, and how Russia has employed the classical tactics of kompromat, forgery, agents of influence and front groups in its modern covert influence campaigns. -

The Glamorization of Espionage in the International Spy Museum

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2015 Counter to Intelligence: The Glamorization of Espionage in the International Spy Museum Melanie R. Wiggins College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Material Culture Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Other American Studies Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Wiggins, Melanie R., "Counter to Intelligence: The Glamorization of Espionage in the International Spy Museum" (2015). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 133. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/133 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Counter to Intelligence: The Glamorization of Espionage in the International Spy Museum A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in American Studies from The College of William and Mary by Melanie Rose Wiggins Accepted for____________________________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _________________________________________________________ Alan Braddock, Director _________________________________________________________ Charlie McGovern _________________________________________________________ -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 Escaping the Honeytrap Representations and Ramifications of the Female Spy on Television Since 1965 Karen K. Burrows Submitted in fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Media and Cultural Studies at the University of Sussex, May 2014 3 University of Sussex Karen K. Burrows Escaping the Honeytrap: Representations and Ramifications of the Female Spy on Television Since 1965 Summary My thesis interrogates the changing nature of the espionage genre on Western television since the middle of the Cold War. It uses close textual analysis to read the progressions and regressions in the portrayal of the female spy, analyzing where her representation aligns with the achievements of the feminist movement, where it aligns with popular political culture of the time, and what happens when the two factors diverge. I ask what the female spy represents across the decades and why her image is integral to understanding the portrayal of gender on television. I explore four pairs of television shows from various eras to demonstrate the importance of the female spy to the cultural landscape. -

AFIO Intelligencer

The Intelligencer Journal of U.S. Intelligence Studies Volume 26 • Number 3 • $15 single copy price Summer-Fall 2021 C O N T E N T S I. Introduction V. AFIO Business and Events Activities During the Pandemic “AFIO Now” — Videos and Podcasts “AFIO Now” Interviews ............................... 3 for members-only and the public .............. 77 II. Current Issues Scholarships, Member Statistics .................. 83 The Evolving Nature of International Relations Chapters, Officers, Activities ....................... 84 and What It Means for Intelligence Intelligence Exhibits & Tours Norman A. Bailey PhD ............................... 5 in Washington Metro Area ...................... 121 Guarding Against Politicization VI. Deaths Robert M. Gates PhD ................................... 7 Deaths in the Intelligence Community ......... 91 Domestic Intelligence - An Enigmatic Piece of the National Security Puzzle VII. Professional Reading Patrick M. Hughes, LTG (USA, Ret.) .......... 15 Reviews by Peter C. Oleson North Korean Control Systems - Insights from a Kazeta: Toxic: A History of Nerve Agents, NKIS Intelligence Officer/Defector From Nazi Germany to Putin’s Russia ............ 119 Jihyun (Amanda) Won MPS and Kim Dong-sik PhD ................................... 35 Doughty: Invading Hitler’s Europe: From Salerno to the Capture of Göring – The Memoir of a U.S. III. Historical Context Intelligence Officer ..................................... 121 A Poem for Yakov Eisenberg — A CIA Operation to Determine If a Ukrainian Company Was Storey: Beating the Nazi Invader: Hitler’s Spies, Saboteurs and Secrets in Britain, 1940 ........... 122 Delivering Missile Parts to Iran Lester Paldy ............................................. 43 Kavanagh: Hitler’s Spies: Lena and the Prelude to Operation Sealion .................... 122 IV. Professional Insights When Intelligence Made a Difference - Assorted Books on China and Chinese Espionage ................................ 124 Part VI Intro — Peter Oleson .................... -

Intelligence Between the World Wars, 1919-1939 from AFIO's

Association of Former Intelligence Officers From AFIO's The Intelligencer 7700 Leesburg Pike, Suite 324 Journal of U.S. Intelligence Studies Falls Church, Virginia 22043 Web: www.afio.com , E-mail: [email protected] Volume 20 • Number 1 • $15 single copy price Spring/Summer 2013 ©2013, AFIO trafficked ports as well as principal economic centers from Berlin to Stockholm to Paris to London to New York and beyond. Despite the propaganda and the Guide to the Study of Intelligence post-1934 dispatch of German “tourists” to several continents, the Third Reich’s secret services were less effective in this work than their Japanese and Soviet counterparts. Intelligence Between The World Wars, 1919-1939 Popular Perceptions From popular culture of the time emerged some “A World Made Safe long lasting images of spies. Out of World War For Deaths of Democracy” I came the Mata Hari story, which purported to typify the seductive role of women in spying. — Referring to this period, Today’s use of “sexpionage” perpetuates that in the final chapter title myth. By the 1930s, the image of the real life in Richard W. Rowan’s 1937 book, The Story of Secret Service (p. 664) spy conducting surveillance out-of-doors in a trench coat, a garb first designed by a London clothier for British officers to wear over their by Douglas L. Wheeler, PhD uniforms in trench warfare, became an almost universal depiction of the spy. The term ”Fifth etween the end of World War I and the onset of Column,” originated in the Spanish Civil War World War II, many intelligence services grew (1936-1939) during the siege of Madrid. -

Foreign Visitors and the Post-Stalin Soviet State

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2016 Porous Empire: Foreign Visitors And The Post-Stalin Soviet State Alex Hazanov Hazanov University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hazanov, Alex Hazanov, "Porous Empire: Foreign Visitors And The Post-Stalin Soviet State" (2016). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2330. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2330 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2330 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Porous Empire: Foreign Visitors And The Post-Stalin Soviet State Abstract “Porous Empire” is a study of the relationship between Soviet institutions, Soviet society and the millions of foreigners who visited the USSR between the mid-1950s and the mid-1980s. “Porous Empire” traces how Soviet economic, propaganda, and state security institutions, all shaped during the isolationist Stalin period, struggled to accommodate their practices to millions of visitors with material expectations and assumed legal rights radically unlike those of Soviet citizens. While much recent Soviet historiography focuses on the ways in which the post-Stalin opening to the outside world led to the erosion of official Soviet ideology, I argue that ideological attitudes inherited from the Stalin era structured institutional responses to a growing foreign presence in Soviet life. Therefore, while Soviet institutions had to accommodate their economic practices to the growing numbers of tourists and other visitors inside the Soviet borders and were forced to concede the existence of contact zones between foreigners and Soviet citizens that loosened some of the absolute sovereignty claims of the Soviet party-statem, they remained loyal to visions of Soviet economic independence, committed to fighting the cultural Cold War, and profoundly suspicious of the outside world. -

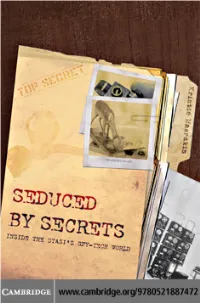

Seduced by Secrets: Inside the Stasi's Spy-Tech World

P1: SBT 9780521188742pre CUNY1276/Macrakis 978 0 521 88747 2 January 17, 2008 14:21 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: SBT 9780521188742pre CUNY1276/Macrakis 978 0 521 88747 2 January 17, 2008 14:21 SEDUCED BY SECRETS More fascinating than fiction, Seduced by Secrets takes the reader inside the real world of one of the most effective and feared spy agencies in history. The book reveals, for the first time, the secret technical methods and sources of the Stasi (East German Ministry for State Security) as it stole secrets from abroad and developed gadgets at home, employing universal, highly guarded techniques often used by other spy and security agencies. Seduced by Secrets draws on secret files from the Stasi archives, includ- ing CIA-acquired material, interviews and friendships, court documents, and unusual visits to spy sites, including “breaking into” a prison, to demonstrate that the Stasi overestimated the power of secrets to solve problems and cre- ated an insular spy culture more intent on securing its power than protecting national security. It re-creates the Stasi’s secret world of technology through biographies of agents, defectors, and officers and by visualizing James Bond– like techniques and gadgets. In this highly original book, Kristie Macrakis adds a new dimension to our understanding of the East German Ministry for State Security by bringing the topic into the realm of espionage history and exiting politically charged commentary. Kristie Macrakis is a professor of the history of science at Michigan State University. She received her Ph.D. in the history of science from Harvard University in 1989 and then spent a postdoctoral year in Berlin, Germany. -

Sexpionage: the Exploitation of Sex by Soviet Intelligence - David Lewis

Sexpionage: The Exploitation of Sex by Soviet Intelligence - David Lewis Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976 - David Lewis - 1976 - Sexpionage: The Exploitation of Sex by Soviet Intelligence - 0151813809, 9780151813803 - file download semumol.pdf May 1, 1982 - Fiction - ISBN:0425053695 - 218 pages - Ian Fleming - Live and Let Die - Beautiful, fortune-telling Solitaire is the prisoner (and tool) of Mr. Big -- master of fear, artist in crime, and Voodoo Baron of Death. James Bond has no time for 1971 - 192 pages - STANFORD:36105036300841 - Women spies - Joseph Bernard Hutton - Women in Espionage by Soviet STANFORD:36105035276018 - Lyman B. Kirkpatrick, Howland H. Sargeant - 1972 - 82 pages - Soviet political warfare techniques; espionage and propaganda in the 1970's - History The Exploitation 212 pages - ISBN:9780595273379 - Lorena Deeming is a successful management consultant married to a worthless husband. His car turns up with the nude and mutilated body of a Palestinian woman official in the - Fiction - The Valley of the Germans - Apr 1, 2003 - Patrick Wilson Gore Sexpionage: The Exploitation of Sex by Soviet Intelligence download Rich Rainey - Fiction - 1983 - Hit Parade - 202 pages - ISBN:0523420692 pdf download the spy I loved - True Crime - Eleanor Philby, Kim Philby - 1968 - UOM:39015015397691 - 175 pages - Kim Philby STANFORD:36105019669014 - E. H. Cookridge - Stories of Famous Women Spies - 1959 - 224 pages - Espionage - Sisters of Delilah The Story of Yuriy Loginov - STANFORD:36105035276026 - 1969 - Barbara Carr - 224 pages - Spy in the Sun - History UOM:39015022376811 - True Crime - 254 pages - Shadow of a Spy - E. H. Cookridge - The Complete Dossier on George Blake - 1967 Sexpionage: Sex This book details the skills of the famous Soviet spies. -

02-05-15 News

SERVING EASTERN SHASTA, NORTHERN LASSEN, WESTERN MODOC & EASTERN SISKIYOU COUNTIES 70 Cents Per Copy Vol. 44 No. 9 Burney, California Telephone (530) 335-4533 FAX (530) 335-5335 Internet: www.im-news.com E-mail: [email protected] May 15, 2002 What’s Happening Audit draws Locally This Week Airport Day fi re with Airport Day is scheduled for Sunday, 7 a.m. to 1 p.m. at the commission Fall River airport. The Eastern Shasta County Sheriff’s Flying BY MEG FOX Commissioners for the Burney Posse, now in its 55th year, will Fire Department expected to dis- be serving a breakfast of ham, cuss their recent audit report with eggs, and pancakes from 7-11 their accountant at the May 8 board a.m. Funds raised are for oper- meeting and were disappointed to ational expenses of the fl ying hear that he is out of the country posse which volunteers its until October. time and aircraft when needed “I’m not willing to do business by the sheriff’s department. For with someone who is not here to more information, telephone answer questions,” said Commis- 336-6273 or 336-5465. sioner Lynn Miller during a sub- sequent discussion about whether the board wanted to sign another Library open house service agreement with Burney An open house will be held Certifi ed Pubic Accountant Charles Saturday from 1-3 p.m. at Pillon. the Fall River Valley Library. “I have a lot of questions,” Miller said. “I’m not questioning the valid- The library’s 14th birthday will ity of the audit, but about why cat- be celebrated as well as the Employees of the Hat Creek egories are the way the are.” beginning of the campaign to Ranger District spent the Board President Donna Sylvester ‘Adopt a Book,’ which allows entire day picking up trash said they could compile their audit the public to choose a book near the junction of Highways questions and FAX them to Pillon to purchase for the children’s 299 and 89.