Sunday Bloody Sunday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ecumenical Movement and the Origins of the League Of

IN SEARCH OF A GLOBAL, GODLY ORDER: THE ECUMENICAL MOVEMENT AND THE ORIGINS OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS, 1908-1918 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by James M. Donahue __________________________ Mark A. Noll, Director Graduate Program in History Notre Dame, Indiana April 2015 © Copyright 2015 James M. Donahue IN SEARCH OF A GLOBAL, GODLY ORDER: THE ECUMENICAL MOVEMENT AND THE ORIGINS OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS, 1908-1918 Abstract by James M. Donahue This dissertation traces the origins of the League of Nations movement during the First World War to a coalescent international network of ecumenical figures and Protestant politicians. Its primary focus rests on the World Alliance for International Friendship Through the Churches, an organization that drew Protestant social activists and ecumenical leaders from Europe and North America. The World Alliance officially began on August 1, 1914 in southern Germany to the sounds of the first shots of the war. Within the next three months, World Alliance members began League of Nations societies in Holland, Switzerland, Germany, Great Britain and the United States. The World Alliance then enlisted other Christian institutions in its campaign, such as the International Missionary Council, the Y.M.C.A., the Y.W.C.A., the Blue Cross and the Student Volunteer Movement. Key figures include John Mott, Charles Macfarland, Adolf Deissmann, W. H. Dickinson, James Allen Baker, Nathan Söderblom, Andrew James M. Donahue Carnegie, Wilfred Monod, Prince Max von Baden and Lord Robert Cecil. -

OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard)

OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard) Vol u m e 2 (15 February 1999 to 15 July 1999) BELFAST: THE STATIONERY OFFICE LTD £70.00 © Copyright The New Northern Ireland Assembly. Produced and published in Northern Ireland on behalf of the Northern Ireland Assembly by the The Stationery Office Ltd, which is responsible for printing and publishing Northern Ireland Assembly publications. ISBN 0 339 80001 1 ASSEMBLY MEMBERS (A = Alliance Party; NIUP = Northern Ireland Unionist Party; NIWC = Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition; PUP = Progressive Unionist Party; SDLP = Social Democratic and Labour Party; SF = Sinn Fein; DUP = Ulster Democratic Unionist Party; UKUP = United Kingdom Unionist Party; UUP = Ulster Unionist Party; UUAP = United Unionist Assembly Party) Adams, Gerry (SF) (West Belfast) Kennedy, Danny (UUP) (Newry and Armagh) Adamson, Ian (UUP) (East Belfast) Leslie, James (UUP) (North Antrim) Agnew, Fraser (UUAP) (North Belfast) Lewsley, Patricia (SDLP) (Lagan Valley) Alderdice of Knock, The Lord (Initial Presiding Officer) Maginness, Alban (SDLP) (North Belfast) Armitage, Pauline (UUP) (East Londonderry) Mallon, Seamus (SDLP) (Newry and Armagh) Armstrong, Billy (UUP) (Mid Ulster) Maskey, Alex (SF) (West Belfast) Attwood, Alex (SDLP) (West Belfast) McCarthy, Kieran (A) (Strangford) Beggs, Roy (UUP) (East Antrim) McCartney, Robert (UKUP) (North Down) Bell, Billy (UUP) (Lagan Valley) McClarty, David (UUP) (East Londonderry) Bell, Eileen (A) (North Down) McCrea, Rev William (DUP) (Mid Ulster) Benson, Tom (UUP) (Strangford) McClelland, Donovan (SDLP) (South -

The Flag Dispute: Anatomy of a Protest

The Flag Dispute: Anatomy of a Protest Nolan, P., Bryan, D., Dwyer, C., Hayward, K., Radford, K., & Shirlow, P. (2014). The Flag Dispute: Anatomy of a Protest. Queen's University Belfast. http://www.qub.ac.uk/research- centres/isctsj/filestore/Filetoupload,481119,en.pdf Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2014 Queen's University Belfast General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:27. Sep. 2021 The Flag Dispute: Anatomy of a Protest Full Report Paul Nolan Dominic Bryan Clare Dwyer Katy Hayward Katy Radford & Peter Shirlow December 2014 Supported by the Community Relations Council & the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Ireland) Published by Queen’s University Belfast 3 ISBN 9781909131248 Cover image: © Pacemaker Press. Acknowledgements The authors of this report are extremely grateful to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the Community Relations Council for funding this research project and its publication. -

Chapter 1 Anthropological Theory

Introduction This dissertation is a historical ethnography of religious diversity in post- revolutionary Nicaragua, a study of religion and politics from the vantage point of Catholics who live in the city of Masaya located on the Pacific side of Nicaragua at the end of the twentieth century. My overarching research question is: How may ethnographically observed patterns in Catholic religious practices in contemporary Nicaragua be understood in historical context? Analysis of religious ritual provides a vehicle for understanding the history of the Nicaraguan struggle to imagine and create a viable nation-state. In Chapter 1, I explain how anthropology benefits by using Max Weber’s social theory as theoretical touchstone for paradigm and theory development. Considering postmodernism problematic for the future of anthropology, I show the value of Weber as a guide to reframing the epistemological questions raised by Michel Foucault and Talal Asad. Situating my discussion of contemporary anthropological theory of religion and ritual within a post-positive discursive framework—provided by a brief comparative analysis of the classical theoretical traditions of Durkheim, Marx, and Weber—I describe the framework used for my analysis of emerging religious pluralism in Nicaragua. My ethnographic and historical methods are discussed in Chapter 2. I utilize the classic methods of participant-observation, including triangulation back and forth between three host families. In every chapter, archival work or secondary historical texts ground the ethnographic data in its relevant historical context. Reflexivity is integrated into my ethnographic research, combining classic ethnography with post-modern narrative methodologies. My attention to reflexivity comes through mainly in the 10 description of my methods and as part of the explanation for my theoretical choices, while the ethnographic descriptions are written up as realist presentations. -

The Issues of the Present Day Make It Particularly Appropriate to Reflect on the Long and Controversial Career of Henry Richard

ThE RELEVancE OF HENRY RichaRD The issues of the present day make it particularly appropriate to reflect on the long and controversial career of Henry Richard. Born in rural Tregaron, in southern Ceredigion in 1812, the issues which he championed have a remarkable contemporary relevance. Since one of Richard’s famous slogans was ‘Trech gwlad nag Arglwydd’ (A land is mightier than its lord) it may appear paradoxical that his career should be re-evaluated by a member of the present (still unelected) House of Lords. For all that, this provides an opportunity to recall one of the most remarkable and courageous Welshmen of the modern world. By (Lord) Kenneth O. Morgan. 36 Journal of Liberal History 79 Summer 2013 ThE RELEVancE OF HENRY RichaRD e was associated with of the Welsh MPs. He did not sym- Richard has not been well served, great causes – notably pathise with agrarian agitation in perhaps in part because his strain Has the proclaimed apos- Wales, nor in pursuing disestablish- of anti-separatist Welsh radicalism tol heddwch (apostle of peace) in the ment of the Church for Wales on does not relate easily to the histori- crusade for world peace which took its own, separately from England. cal antecedents of Plaid Cymru. him from the Peace Treaty of Paris He was bracketed with other ‘old However, Richard represents in 1856 to that of Berlin in 1878, and hands’, senior Welsh Liberals like something of much importance in in the challenge to militarism and Lewis Llewellyn Dillwyn, Sir Hus- the spectrum of nineteenth-cen- imperialism which led to confron- sey Vivian and Fuller-Maitland. -

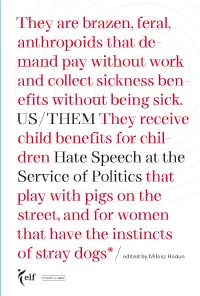

Here: on Hate Speech

They are brazen, feral, anthropoids that de- mand pay without work and collect sickness ben- efits without being sick. US / THEM They receive child benefits for chil- dren Hate Speech at the Service of Politics that play with pigs on the street, and for women that have the instincts of stray dogs * / edited by Miłosz Hodun LGBT migrants Roma Muslims Jews refugees national minorities asylum seekers ethnic minorities foreign workers black communities feminists NGOs women Africans church human rights activists journalists leftists liberals linguistic minorities politicians religious communities Travelers US / THEM European Liberal Forum Projekt: Polska US / THEM Hate Speech at the Service of Politics edited by Miłosz Hodun 132 Travelers 72 Africans migrants asylum seekers religious communities women 176 Muslims migrants 30 Map of foreign workers migrants Jews 162 Hatred refugees frontier workers LGBT 108 refugees pro-refugee activists 96 Jews Muslims migrants 140 Muslims 194 LGBT black communities Roma 238 Muslims Roma LGBT feminists 88 national minorities women 78 Russian speakers migrants 246 liberals migrants 8 Us & Them black communities 148 feminists ethnic Russians 20 Austria ethnic Latvians 30 Belgium LGBT 38 Bulgaria 156 46 Croatia LGBT leftists 54 Cyprus Jews 64 Czech Republic 72 Denmark 186 78 Estonia LGBT 88 Finland Muslims Jews 96 France 64 108 Germany migrants 118 Greece Roma 218 Muslims 126 Hungary 20 Roma 132 Ireland refugees LGBT migrants asylum seekers 126 140 Italy migrants refugees 148 Latvia human rights refugees 156 Lithuania 230 activists ethnic 204 NGOs 162 Luxembourg minorities Roma journalists LGBT 168 Malta Hungarian minority 46 176 The Netherlands Serbs 186 Poland Roma LGBT 194 Portugal 38 204 Romania Roma LGBT 218 Slovakia NGOs 230 Slovenia 238 Spain 118 246 Sweden politicians church LGBT 168 54 migrants Turkish Cypriots LGBT prounification activists Jews asylum seekers Europe Us & Them Miłosz Hodun We are now handing over to you another publication of the Euro- PhD. -

Political Party Profiles 2012

Risk profiles 2013 update We have developed formal processes to enable us to deploy our resources more effectively. This includes the generation of risk profiles to inform our audit strategy. These profiles bring together various different pieces of information relating to parties Returns data 2010 - 2012 Next update November 2014 Find out more about our policy and risk profiles on our website at: http://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/party-finance/enforcement/risk-profiles Key Financial risk criteria This indicates the financial scale, cash flow and past accounting accuracy of the party. We weight these indicators to Profiled A-C produce a rating of A, B or C for each party. A rating of ‘C’ may indicate, for instance, a party with high levels of debt that has had Compliance risk criteria This indicates a party’s level of compliance with their statutory obligations over a period of three years. The levels of Profiled high, compliance are broadly categorised as being either ‘high’, ‘medium’ or ‘low’. medium or low Operational risk criteria This helps to illustrate the scale of a party’s activity and therefore how significant the impact of a failure to comply Profiled 1-5 with the regulatory requirements might be. The higher the number is the larger the scale of operation a party has. EC Reference Number Entity name Register Financial Compliance Operational Likelihood of audit 704 1st 4 Kirkby Great Britain A High 1 Low 210 21st Century Conservative Democrats Great Britain A High 1 Low 2115 21st Century Democracy Great Britain A High 1 Low -

The Flag Dispute: Anatomy of a Protest

The Flag Dispute: Anatomy of a Protest Nolan, P., Bryan, D., Dwyer, C., Hayward, K., Radford, K., & Shirlow, P. (2014). The Flag Dispute: Anatomy of a Protest. Queen's University Belfast. http://www.qub.ac.uk/research- centres/isctsj/filestore/Filetoupload,481119,en.pdf Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2014 Queen's University Belfast General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:07. Oct. 2021 The Flag Dispute: Anatomy of a Protest Full Report Paul Nolan Dominic Bryan Clare Dwyer Katy Hayward Katy Radford & Peter Shirlow December 2014 Supported by the Community Relations Council & the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Ireland) Published by Queen’s University Belfast 3 ISBN 9781909131248 Cover image: © Pacemaker Press. Acknowledgements The authors of this report are extremely grateful to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the Community Relations Council for funding this research project and its publication. -

CASE STUDIES on CONSTITUTION BUILDING Professor Robert

Mapping the Path towards Codifying - or Not Codifying - the UK Constitution CASE STUDIES ON CONSTITUTION BUILDING Professor Robert Blackburn July 2014 Mapping the Path towards Codifying - or Not Codifying - the UK Constitution _____________________________________________________________________ This collection of case studies forms part of the programme of research commissioned by the House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee from Professor Robert Blackburn, Director of the Centre for Political and Constitutional Studies at King's College London, for its inquiry into Mapping the Path towards Codifying – or Not Codifying – the UK Constitution, conducted with the support of the Nuffield Foundation and Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Editor _____________________________________________________________________ ROBERT BLACKBURN is Professor of Constitutional Law, King’s College London. He is a Solicitor of the Senior Courts, and author of public law titles in Halsbury's Laws of England, including Constitutional and Administrative Law (Volume 20), The Crown and Crown Proceedings (Volume 29) and Parliament (Volume 78). His academic works include books on The Electoral System in Britain, King and Country, Parliament: Functions, Practice and Procedure, Fundamental Rights in Europe, Rights of Citizenship, The Meeting of Parliament and Constitutional Reform. He is a former Acting Head of the School of Law, and is currently Director of both the Centre for Political and Constitutional Studies (research unit) and the Institute -

Dáil Éireann

Vol. 915 Monday, No. 1 27 June 2016 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DÁIL ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) 27/06/2016A00100United Kingdom Referendum on European Union Membership: Statements � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 2 DÁIL ÉIREANN Dé Luain, 27 Meitheamh 2016 Monday, 27 June 2016 Chuaigh an Ceann Comhairle i gceannas ar 12 p�m� Paidir. Prayer. 27/06/2016A00100United Kingdom Referendum on European Union Membership: Statements 27/06/2016A00200The Taoiseach: Last Thursday, a majority of the United Kingdom electorate made a deci- sion that will have a lasting impact on the future of these islands� On Friday, the Prime Minister, Mr� David Cameron, telephoned me to inform me personally of the result and of his intention to resign� He thanked the Irish Government for its support all through the process� He committed to ensuring there would be early bilateral engagement at senior official level on key issues now arising� These include Northern Ireland, the Border and the common travel area� That high level contact between officials will take place this week initially. While this is not the result the Government wanted, we fully respect the voters’ sovereign choice in the UK� Both I and my colleagues in government have been clear all along that a Leave result in the referendum would have significant implications at a national, bilateral and international level� Many Members also supported that view and helpfully engaged in advocating Ireland’s position, particularly among the Irish and the Irish-connected communities that had a vote� I believe a cross-party approach will be valuable in the time ahead� I briefed Opposition leaders last Friday on contingency plans and the next steps in the EU-UK negotiation process� I was encouraged to hear that Members were willing to use their influence through their own party affiliations in Europe to ensure Ireland’s position is well understood. -

2.3 Political Catholicism – Distinct Political Movement Or Ideology?

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details POLITICAL CATHOLICISM AND EUROSCEPTICISM The deviant case of Poland in a comparative perspective Bartosz Napieralski University of Sussex Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2015 ii I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be submitted in whole or in part to another university for the award of any degree. However, the thesis incorporates, to the extent indicated below, material already submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in European Politics, Business and Law, which was awarded by the University of Surrey. Parts of section 1.2.2 on the definition and causality of Euroscepticism (pages 9-13 and 15-16), as well as paragraphs on pages: 99, 113-114 and 129. Signature: iii Table of contents List of Tables ............................................................................................................................ vi List of Figures .......................................................................................................................... -

Northern Ireland Peace Monitoring Report

Community Relations Council Northern Ireland Peace Monitoring Report Number Three March 2014 Paul Nolan Peace Monitoring Report The Northern Ireland Peace Monitoring Report Number Three Paul Nolan March 2014 3 Peace Monitoring Report Data sources and acknowledgements This report draws mainly on statistics that are in the public domain. Data sets from various government departments and public bodies in Northern Ireland have been used and, in order to provide a wider context, comparisons are made which draw upon figures produced by government departments and public bodies in England, Scotland, Wales and the Republic of Ireland. Using this variety of sources means there is no standard model that applies across the different departments and jurisdictions. Many organisations have also changed the way in which they collect their data over the years, which means that in some cases it has not been possible to provide historical perspective on a consistent basis. For some indicators, only survey-based data is available. When interpreting statistics from survey data, such as the Labour Force Survey, it is worth bearing in mind that they are estimates associated with confidence intervals (ranges in which the true value is likely to lie). In other cases where official figures may not present the full picture, survey data is included because it may provide a more accurate estimate – thus, for example, findings from the Northern Ireland Crime Survey are included along with the official crime statistics from the PSNI. The production of the report has been greatly assisted by the willing cooperation of many statisticians and public servants, particularly those from the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, the PSNI and the various government departments.