The Flag Dispute: Anatomy of a Protest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

Sunday Bloody Sunday

Sunday Bloody Sunday An Analysis of Representations of the Troubles in Northern Irish Curricula and Teaching Material and their Didactic Implications for Political Learning Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Magisters der Geisteswissenschaft an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz am Institut für Geschichte.: vorgelegt von Moritz DEININGER Begutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr.phil Alois Ecker Graz, 2019 Ehrenwörtliche Erklärung Ich erkläre ehrenwörtlich, dass ich die vorliegende Diplomarbeit selbstständig und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Quellen verfasst und die den benutzten Quellen wörtlich oder inhaltlich entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. Graz, September 2019 Moritz Deininger “The road from mutual distrust to genuine cooperation is a rocky one.” - Smith 2005: xv 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Preliminary Theoretic Considerations and Methodological Approaches ........................ 5 2. Historic Overview ................................................................................................................ 15 2.1 The Troubles .................................................................................................................. 35 2.2 Current Standstill ............................................................................................................ 62 2.3 Descriptions of the Conflict .......................................................................................... -

Investigating Fatal Police Shootings Using the Human Factors Analysis and Classification Framework (HFACS)

Police Practice and Research An International Journal ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gppr20 Investigating fatal police shootings using the human factors analysis and classification framework (HFACS) Paul McFarlane & Amaria Amin To cite this article: Paul McFarlane & Amaria Amin (2021): Investigating fatal police shootings using the human factors analysis and classification framework (HFACS), Police Practice and Research, DOI: 10.1080/15614263.2021.1878893 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2021.1878893 © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 01 Feb 2021. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 239 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gppr20 POLICE PRACTICE AND RESEARCH https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2021.1878893 ARTICLE Investigating fatal police shootings using the human factors analysis and classification framework (HFACS) Paul McFarlane and Amaria Amin Department of Security and Crime Science, Institute For Global City Policing, University College London, London, UK ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Fatal police shootings are highly contentious and troublesome for norma Received 4 February 2020 tive standards of police legitimacy. Fatal police shooting investigations are Accepted 9 January 2021 often criticised because they lack impartiality, transparency and rigour. To KEYWORDS assist policing practitioners and policymakers in the UK and beyond with Fatal police shootings; managing these issues, we present a new analytical framework for inves Human Factors Analysis and tigating fatal policing shootings. -

A ONU Na Resolução De Conflitos: O Caso De Timor-Leste* - Francisco Proença Garcia, Mónica Dias E Raquel Duque – Pp 1-12 Oportunidades De Prevenção De Conflitos

OBSERVARE Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa e-ISSN: 1647-7251 Vol. 10, Nº. 2 (Novembro 2019-Abril 2020) Vol 10, Nº. 2 (Novembro 2019-Abril 2020) https://doi.org/10.26619/1647-7251.10.2 ARTIGOS A ONU na resolução de conflitos: o caso de Timor-Leste* - Francisco Proença Garcia, Mónica Dias e Raquel Duque – pp 1-12 Oportunidades de prevenção de conflitos. Lições da Comunidade Económica dos Estados da África Ocidental (CEDEAO)* - Jara Cuadrado – pp 13-34 A influência das alterações climáticas na escalada do conflito comunal entre pastores e agricultores: o caso da etnia Fulani na Nigéria* - Gustavo Furini – pp 35-55 União Europeia, Rússia e o caso do MH17: uma análise das narrativas estratégicas (2014-2019)* – Paulo Ramos e Alena Vieira – pp 56-71 Global Security Assemblages: mapping the field* - Jovana Jezdimirovic Ranito – pp 72-86 Por que é importante uma perspetiva regional quando analisamos conflitos civis no Médio Oriente e no Norte de África? - Samer Hamati – pp 87-97 La cooperación de China en África en el área de infraestructura de conectividad física. El caso de la vía ferroviaria Mombasa-Nairobi - María Noel Dussort e Agustina Marchetti – pp 98-117 A iniciativa dos 3 mares: geopolítica e infraestruturas - Bernardo Calheiros – pp 118-132 Derechos de los migrantes: apuntes a la jurisprudência de la corte interamericana de derechos humanos - María Teresa Palacios Sanabria – pp 133-150 Entre a liberdade de contrato e o princípio da boa-fé: uma visão interna da reforma do direito privado do Cazaquistão - Kamal Sabirov, Venera Konussova e Marat Alenov – pp 151-161 A Observância do Direito Humano à Liberdade contra a Tortura na Atividade Profissional da Polícia Nacional da Ucrânia (Artigo 3 da Convenção Para a Proteção dos Direitos Humanos e das Liberdades Fundamentais) - Andrii Voitsikhovskyi, Vadym Seliukov, Oleksandr Bakumov e Olena Ustymenko – pp 162-175 * Dossiê temático de artigos apresentados na 1ª Conferência Internacional de Resolução de Conflitos e Estudos da Paz realizada na UAL a 29 e 30 de Novembro de 2018. -

Will of Dame Anne Packington.Pdf

TNA PROB/11/47 Will of Dame Anne Packington In the name of the father and of the sonne and of the holy ghoste The xxvjth daie of the monneth of Aprell in the yere of incarnacion of our Lorde Jesus Christe 1563. I Dame Anne Packington Widdow late the wief of Sir John Pakington knight deceased being in the hole mynde and in health of boddie blessed be almightie god remembringe and calling to mynde the mutablitie of this transitory lief knowing my selfe mortall and subiecte to death whereunto every creature is borne. Doe make ordeine and declare this my present Testament and last will in manner and fourme followinge ffirst and principally I bequeath my soule to the blissed Trinitie and the holly company of heaven my bodie to be buried in that parishe churche Where it shall please god to ende my lief or where my executors shall thinke mete at thende of the highe aulter Wheras the sepulture was vsed moste commonly to stande if the rome and place maie be suffered or els at thother ende of the high alter And I will that my executors shall cause a Tombe of marble to be made and sett over my bodie for the making Wherof I bequeath twenty markes or more if it come to more/ And I bequethe to xxti poore men and women every one a blacke gowne of an honest clothe or good frise Wherof xij of them shall beare at my buriall xij torches and iiij of them shall beare forever greate tapers if the lawes of this Realme will so permitt and suffer Item I bequeath amonge the poore househoulders dwelling in that parrish where I shalbe buried twelve pennce a pece/ And among all other people comming to my buriall ij d. -

The Ecumenical Movement and the Origins of the League Of

IN SEARCH OF A GLOBAL, GODLY ORDER: THE ECUMENICAL MOVEMENT AND THE ORIGINS OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS, 1908-1918 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by James M. Donahue __________________________ Mark A. Noll, Director Graduate Program in History Notre Dame, Indiana April 2015 © Copyright 2015 James M. Donahue IN SEARCH OF A GLOBAL, GODLY ORDER: THE ECUMENICAL MOVEMENT AND THE ORIGINS OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS, 1908-1918 Abstract by James M. Donahue This dissertation traces the origins of the League of Nations movement during the First World War to a coalescent international network of ecumenical figures and Protestant politicians. Its primary focus rests on the World Alliance for International Friendship Through the Churches, an organization that drew Protestant social activists and ecumenical leaders from Europe and North America. The World Alliance officially began on August 1, 1914 in southern Germany to the sounds of the first shots of the war. Within the next three months, World Alliance members began League of Nations societies in Holland, Switzerland, Germany, Great Britain and the United States. The World Alliance then enlisted other Christian institutions in its campaign, such as the International Missionary Council, the Y.M.C.A., the Y.W.C.A., the Blue Cross and the Student Volunteer Movement. Key figures include John Mott, Charles Macfarland, Adolf Deissmann, W. H. Dickinson, James Allen Baker, Nathan Söderblom, Andrew James M. Donahue Carnegie, Wilfred Monod, Prince Max von Baden and Lord Robert Cecil. -

Beyond the Religious Divide

Beyond the Religious Divide 1 CONTENTS PART 1: INTRODUCTION: Review of political structures PART 2: THE PEOPLE AND THE STATE: A proposed Constitution and Political Structures PART 3: A PROPOSED BILL OF RIGHTS PART 4: TWO ECONOMIC PAPERS: John Simpson (Queens University, Belfast); Dr. T.K. Whitaker (former Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland. N.B. Part 1 is only available at present. 2 INTRODUCTION Why is it in Northern Ireland that Conservative Protestants and Conservative Roman Catholics, and Socialist Roman Catholics and Liberal Protestants and Liberal Roman Catholics cannot come together in proper political parties to contest and win elections on social and economic policies? Political unity in Northern Ireland between Protestants and Roman Catholics with the same political ideology is not a new concept. At certain stages in our turbulent history it has been achieved to varying degrees of success, but for one reason or another has never been sustained long enough to be of any real consequence. The evolution of proper politics would no doubt remove many of Northern Ireland’s problems and would certainly allow the people of Northern Ireland to decide their elected representatives on a political basis rather than religious bigotry and sectarian hatred. Without the evolution of proper politics the people of Northern Ireland will continually be manipulated by sectarian politicians and anti-secularist clergy who make no contribution to the social and economic well-being of the people or the country but only continue to fan the flames -

1 Demographic Change and Conflict in Northern Ireland

Demographic Change and Conflict in Northern Ireland: Reconciling Qualitative and Quantitative Evidence Eric Kaufmann James Fearon and David Laitin (2003) famously argued that there is no connection between the ethnic fractionalisation of a state’s population and its likelihood of experiencing ethnic conflict. This has contributed towards a general view that ethnic demography is not integral to explaining ethnic violence. Furthermore, sophisticated attempts to probe the connection between ethnic shifts and conflict using large-N datasets have failed to reveal a convincing link. Thus Toft (2007), using Ellingsen's dataset for 1945-94, finds that in world-historical perspective, since 1945, ethno-demographic change does not predict civil war. Toft developed hypotheses from realist theories to explain why a growing minority and/or shrinking majority might set the conditions for conflict. But in tests, the results proved inconclusive. These cross-national data-driven studies tell a story that is out of phase with qualitative evidence from case study and small-N comparative research. Donald Horowitz cites the ‘fear of extinction’ voiced by numerous ethnic group members in relation to the spectre of becoming minorities in ‘their’ own homelands due to differences of fertility and migration. (Horowitz 1985: 175-208) Slack and Doyon (2001) show how districts in Bosnia where Serb populations declined most against their Muslim counterparts during 1961-91 were associated with the highest levels of anti-Muslim ethnic violence. Likewise, a growing field of interest in African studies concerns the problem of ‘autochthony’, whereby ‘native’ groups wreak havoc on new settlers in response to the perception that migrants from more advanced or dense population regions are ‘swamping’ them. -

Legacies of the Troubles and the Holy Cross Girls Primary School Dispute

Glencree Journal 2021 “IS IT ALWAYS GOING BE THIS WAY?”: LEGACIES OF THE TROUBLES AND THE HOLY CROSS GIRLS PRIMARY SCHOOL DISPUTE Eimear Rosato 198 Glencree Journal 2021 Legacy of the Troubles and the Holy Cross School dispute “IS IT ALWAYS GOING TO BE THIS WAY?”: LEGACIES OF THE TROUBLES AND THE HOLY CROSS GIRLS PRIMARY SCHOOL DISPUTE Abstract This article examines the embedded nature of memory and identity within place through a case study of the Holy Cross Girls Primary School ‘incident’ in North Belfast. In 2001, whilst walking to and from school, the pupils of this primary school aged between 4-11 years old, faced daily hostile mobs of unionist/loyalists protesters. These protesters threw stones, bottles, balloons filled with urine, fireworks and other projectiles including a blast bomb (Chris Gilligan 2009, 32). The ‘incident’ derived from a culmination of long- term sectarian tensions across the interface between nationalist/republican Ardoyne and unionist/loyalist Glenbryn. Utilising oral history interviews conducted in 2016–2017 with twelve young people from the Ardoyne community, it will explore their personal experiences and how this event has shaped their identities, memory, understanding of the conflict and approaches to reconciliation. KEY WORDS: Oral history, Northern Ireland, intergenerational memory, reconciliation Introduction Legacies and memories of the past are engrained within territorial boundaries, sites of memory and cultural artefacts. Maurice Halbwachs (1992), the founding father of memory studies, believed that individuals as a group remember, collectively or socially, with the past being understood through ritualism and symbols. Pierre Nora’s (1989) research builds and expands on Halbwachs, arguing that memory ‘crystallises’ itself in certain sites where a sense of historical continuity persists. -

The Performance of Intersectionality on the 21St Century Stand-Up

The Performance of Intersectionality on the 21st Century Stand-Up Comedy Stage © 2018 Rachel Eliza Blackburn M.F.A., Virginia Commonwealth University, 2013 B.A., Webster University Conservatory of Theatre Arts, 2005 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Theatre and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Dr. Nicole Hodges Persley Dr. Katie Batza Dr. Henry Bial Dr. Sherrie Tucker Dr. Peter Zazzali Date Defended: August 23, 2018 ii The dissertation committee for Rachel E. Blackburn certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Performance of Intersectionality on the 21st Century Stand-Up Comedy Stage Chair: Dr. Nicole Hodges Persley Date Approved: Aug. 23, 2018 iii Abstract In 2014, Black feminist scholar bell hooks called for humor to be utilized as political weaponry in the current, post-1990s wave of intersectional activism at the National Women’s Studies Association conference in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Her call continues to challenge current stand-up comics to acknowledge intersectionality, particularly the perspectives of women of color, and to encourage comics to actively intervene in unsettling the notion that our U.S. culture is “post-gendered” or “post-racial.” This dissertation examines ways in which comics are heeding bell hooks’s call to action, focusing on the work of stand-up artists who forge a bridge between comedy and political activism by performing intersectional perspectives that expand their work beyond the entertainment value of the stage. Though performers of color and white female performers have always been working to subvert the normalcy of white male-dominated, comic space simply by taking the stage, this dissertation focuses on comics who continue to embody and challenge the current wave of intersectional activism by pushing the socially constructed boundaries of race, gender, sexuality, class, and able-bodiedness. -

Evaluation of the Building Peace Through the Arts: Re-Imaging Communities Programme

Evaluation of the Building Peace through the Arts: Re-Imaging Communities Programme Final Report January 2016 CONTENTS 1. BUILDING PEACE THROUGH THE ARTS ................................................... 5 1.1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 5 1.2. Operational Context ............................................................................................. 5 1.3. Building Peace through the Arts ......................................................................... 6 1.4. Evaluation Methodology ....................................................................................... 8 1.5. Document Contents .............................................................................................. 8 2. PROGRAMME APPLICATIONS & AWARDS ............................................ 10 2.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 10 2.2 Stage One Applications and Awards ................................................................ 10 2.3 Stage Two Applications and Awards ................................................................ 11 2.4 Project Classification .......................................................................................... 12 2.5 Non-Progression of Enquiries and Awards ...................................................... 16 2.6 Discussion ........................................................................................................... -

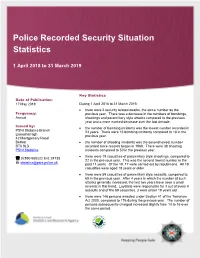

Security Statistics for 2018/19

Police Recorded Security Situation Statistics 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019 Key Statistics Date of Publication: 17 May 2019 During 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019: there were 2 security related deaths, the same number as the Frequency: previous year. There was a decrease in the numbers of bombings, Annual shootings and paramilitary style attacks compared to the previous year and a more marked decrease over the last decade. Issued by: the number of bombing incidents was the lowest number recorded in PSNI Statistics Branch 23 years. There were 15 bombing incidents compared to 18 in the Lisnasharragh previous year. 42 Montgomery Road Belfast the number of shooting incidents was the second lowest number BT6 9LD recorded since records began in 1969. There were 38 shooting PSNI Statistics incidents compared to 50 in the previous year. there were 19 casualties of paramilitary style shootings, compared to 02890 650222 Ext. 24135 22 in the previous year. This was the second lowest number in the [email protected] past 11 years. Of the 19, 17 were carried out by republicans. All 19 casualties were aged 18 years or older. there were 59 casualties of paramilitary style assaults, compared to 65 in the previous year. After 4 years in which the number of such attacks generally increased, the last two years have seen a small reversal in this trend. Loyalists were responsible for 3 out of every 4 assaults and of the 59 casualties, 3 were under 18 years old. there were 146 persons arrested under Section 41 of the Terrorism Act 2000, compared to 176 during the previous year.