Students' Perceptions Concerning the Site Visit in History, ICSS, Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infected Areas As on 1 September 1988 — Zones Infectées Au 1Er Septembre 1988 for Criteria Used in Compiling This List, See No

W kly Epiâem. Rec. No. 36-2 September 1S88 - 274 - Relevé àptdém, hebd N° 36 - 2 septembre 1988 GERMANY, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF ALLEMAGNE, RÉPUBLIQUE FÉDÉRALE D’ Insert — Insérer: Hannover — • Gesundheitsamt des Landkreises, Hildesheimer Str. 20 (Niedersachsen Vaccinating Centre No. HA 4) Delete — Supprimer: Hannover — • Gesundheitsamt (Niedersachsen Vaccinating Centre No. HA 3) Insert — Insérer: • Gesundheitsamt der Landeshauptstadt, Weinstrasse 2 (Niedersachsen Vaccinating Centre No. HA 3) SPAIN ESPAGNE Insert - Insérer: La Rioja RENEWAL OF PAID SUBSCRIPTIONS RENOUVELLEMENT DES ABONNEMENTS PAYANTS To ensure that you continue to receive the Weekly Epidemio Pour continuer de recevoir sans interruption le R elevé épidémiolo logical Record without interruption, do not forget to renew your gique hebdomadaire, n’oubliez pas de renouveler votre abonnement subscription for 1989. This can be done through your sales pour 1989. Ceci peut être fait par votre dépositaire. Pour les pays où un agent. For countries without appointed sales agents, please dépositaire n’a pas été désigné, veuillez écrire à l’Organisation mon write to : World Health Organization, Distribution and Sales, diale de la Santé, Service de Distribution et de Vente, 1211 Genève 27, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland. Be sure to include your sub Suisse. N’oubliez pas de préciser le numéro d’abonnement figurant sur scriber identification number from the mailing label. l’étiquette d’expédition. Because of the general increase in costs, the annual subscrip En raison de l’augmentation générale des coûts, le prix de l’abon tion rate will be increased to S.Fr. 150 as from 1 January nement annuel sera porté à Fr.s. 150 à partir du 1er janvier 1989. -

Perak Heads of State Department and Local Authority Directory 2020

PERAK HEADS OF STATE DEPARTMENT AND LOCAL AUTHORITY DIRECTORY 2020 DISTRIBUTION LIST NO. DESIGNATION / ADDRESS NAME OF TELEPHONE / FAX HEAD OF DEPARTMENT 1. STATE FINANCIAL OFFICER, YB Dato’ Zulazlan Bin Abu 05-209 5000 (O) Perak State Finance Office, Hassan *5002 Level G, Bangunan Perak Darul Ridzuan, 05-2424488 (Fax) Jalan Panglima Bukit Gantang Wahab, [email protected] 30000 IPOH 2. PERAK MUFTI, Y.A.Bhg. Tan Sri Dato’ Seri Haji 05-2545332 (O) State Mufti’s Office, Harussani Bin Haji Zakaria 05-2419694 (Fax) Level 5, Kompleks Islam Darul Ridzuan, Jalan Panglima Bukit Gantang Wahab, [email protected] 30000 IPOH. 3. DIRECTOR, Y.A.A. Dato Haji Asa’ari Bin 05-5018400 (O) Perak Syariah Judiciary Department, Haji Mohd Yazid 05-5018540 (Fax) Level 5, Kompleks Mahkamah Syariah Perak, Jalan Pari, Off Jalan Tun Abdul Razak, [email protected] 30020 IPOH. 4. CHAIRMAN, Y.D.H Dato’ Pahlawan Hasnan 05-2540615 (O) Perak Public Service Commission, Bin Hassan 05-2422239 (Fax) E-5-2 & E-6-2, Menara SSI, SOHO 2, Jalan Sultan Idris Shah, [email protected] 30000 IPOH. 5. DIRECTOR, YBhg. Dato’ Mohamad Fariz 05-2419312 (D) Director of Land and Mines Office, Bin Mohamad Hanip 05-209 5000/5170 (O) Bangunan Sri Perak Darul Ridzuan, 05-2434451 (Fax) Jalan Panglima Bukit Gantang Wahab, [email protected] 30000 IPOH. 6. DIRECTOR, (Vacant) 05-2454008 (D) Perak Public Works Department, 05-2454041 (O) Jalan Panglima Bukit Gantang Wahab, 05-2537397 (Fax) 30000 IPOH. 7. DIRECTOR, TPr. Jasmiah Binti Ismail 05-209 5000 (O) PlanMalaysia@Perak, *5700 Town and Country Planning Department, [email protected] 05-2553022 (Fax) Level 7, Bangunan Kerajaan Negeri, Jalan Panglima Bukit Gantang Wahab, 30000 IPOH. -

112 Sime Darby Berhad Annual Report 2016 Innovating

112 Innovating for the Future Annual Report 2016 Sime Darby Berhad Sime Darby Berhad Annual Report 2016 Corporate Governance 113 STATEMENT ON CORPORATE GOVERNANCE “Our governance processes, culture of integrity and openness, and a diversity of perspective continue to support the Board in delivering a sustainable and successful Sime Darby Group.” TAN SRI DATO’ ABDUL GHANI OTHMAN Chairman CHAIRMAN’S OVERVIEW Board Effectiveness The Board attaches the highest priority to I continue to keep the membership of our Board corporate governance and as a Board, we provide under review, looking for exceptional candidates to strong leadership in setting standards and values join us and ensuring that we have the right mix of for our company. As Chairman, I passionately skills, experience and background. believe in creating and delivering long term sustainable value to our stakeholders. Our Our overriding priority in any new appointment is to governance processes, culture of integrity and select the best candidate with a view to achieving a openness, and a diversity of perspective continue high-performing Board, in line with the evolving to support the Board in delivering a sustainable circumstances and needs of the Group. The and successful Sime Darby Group. Directors of the Board are selected on the criteria of proven skill and ability in their particular field of Our Board Committees continue to play a vital role endeavour, and a diversity of outlook and in supporting the Board. Our governance structure experience which directly benefits the operation of is shown on page 122. Each Board Committee chair the Board as the custodian of the business. -

1 Chapter 1 Introduction As a Chinese Buddhist in Malaysia, I Have Been

Chapter 1 Introduction As a Chinese Buddhist in Malaysia, I have been unconsciously entangled in a historical process of the making of modern Buddhism. There was a Chinese temple beside my house in Penang, Malaysia. The main deity was likely a deified imperial court officer, though no historical record documented his origin. A mosque serenely resided along the main street approximately 50 meters from my house. At the end of the street was a Hindu temple decorated with colorful statues. Less than five minutes’ walk from my house was a Buddhist association in a two-storey terrace. During my childhood, the Chinese temple was a playground. My friends and I respected the deities worshipped there but sometimes innocently stole sweets and fruits donated by worshippers as offerings. Each year, three major religious events were organized by the temple committee: the end of the first lunar month marked the spring celebration of a deity in the temple; the seventh lunar month was the Hungry Ghost Festival; and the eighth month honored, She Fu Da Ren, the temple deity’s birthday. The temple was busy throughout the year. Neighbors gathered there to chat about national politics and local gossip. The traditional Chinese temple was thus deeply rooted in the community. In terms of religious intimacy with different nearby temples, the Chinese temple ranked first, followed by the Hindu temple and finally, the mosque, which had a psychological distant demarcated by racial boundaries. I accompanied my mother several times to the Hindu temple. Once, I asked her why she prayed to a Hindu deity. -

Data Standardization Analysis to Form Geo-Demographics Classification Profiles Using K-Means Algorithms

GEOGRAFIA OnlineTM Malaysian Journal of Society and Space 12 issue 6 (34 - 42) 34 Themed issue on current social, economic, cultural and spatial dynamics of Malaysia’s transformation © 2016, ISSN 2180-2491 Improving the tool for analyzing Malaysia’s demographic change: Data standardization analysis to form geo-demographics classification profiles using k-means algorithms Kamarul Ismail1, Nasir Nayan1, Siti Naielah Ibrahim1 1Jabatan Geografi dan Alam Sekitar, Fakulti Sains Kemanusiaan, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, 35900 Tanjong Malim, Perak Correspondence: Kamarul Ismail (email: [email protected]) Abstract Clustering is one of the important methods in data exploratory in this era because it is widely applied in data mining.Clustering of data is necessary to produce geo-demographic classification where k-means algorithm is used as cluster algorithm. K-means is one of the methods commonly used in cluster algorithm because it is more significant. However, before any data are executed on cluster analysis it is necessary to conduct some analysis to ensure the variable used in the cluster analysis is appropriate and does not have a recurring information. One analysis that needs to be done is the standardization data analysis. This study observed which standardization method was more effective in the analysis process of Malaysia’s population and housing census data for the Perak state. The rationale was that standardized data would simplify the execution of k-means algorithm. The standardized methods chosen to test the data accuracy were the z-score and range standardization method. From the analysis conducted it was found that the range standardization method was more suitable to be used for the data examined. -

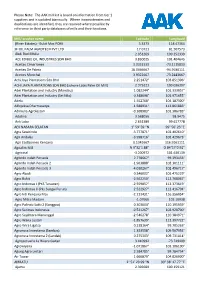

The AAK Mill List Is Based on Information from Tier 1 Suppliers and Is Updated Biannually

Please Note: The AAK mill list is based on information from tier 1 suppliers and is updated biannually. Where inconsistencies and duplications are identified, they are resolved where possible by reference to third party databases of mills and their locations. Mill/ crusher name Latitude Longitude (River Estates) - Bukit Mas POM 5.3373 118.47364 3F OIL PALM AGROTECH PVT LTD 17.0721 81.507573 Abdi Budi Mulia 2.051269 100.252339 ACE EDIBLE OIL INDUSTRIES SDN BHD 3.830025 101.404645 Aceites Cimarrones 3.0352333 -73.1115833 Aceites De Palma 18.0466667 -94.9186111 Aceites Morichal 3.9322667 -73.2443667 Achi Jaya Plantations Sdn Bhd 2.251472° 103.051306° ACHI JAYA PLANTATIONS SDN BHD (Johore Labis Palm Oil Mill) 2.375221 103.036397 Adei Plantation and Industry (Mandau) 1.082244° 101.333057° Adei Plantation and Industry (Sei Nilo) 0.348098° 101.971655° Adela 1.552768° 104.187300° Adhyaksa Dharmasatya -1.588931° 112.861883° Adimulia Agrolestari -0.108983° 101.386783° Adolina 3.568056 98.9475 Aek Loba 2.651389 99.617778 AEK NABARA SELATAN 1° 59' 59 "N 99° 56' 23 "E Agra Sawitindo -3.777871° 102.402610° Agri Andalas -3.998716° 102.429673° Agri Eastborneo Kencana 0.1341667 116.9161111 Agrialim Mill N 9°32´1.88" O 84°17´0.92" Agricinal -3.200972 101.630139 Agrindo Indah Persada 2.778667° 99.393433° Agrindo Indah Persada 2 -1.963888° 102.301111° Agrindo Indah Persada 3 -4.010267° 102.496717° Agro Abadi 0.346002° 101.475229° Agro Bukit -2.562250° 112.768067° Agro Indomas I (PKS Terawan) -2.559857° 112.373619° Agro Indomas II (Pks Sungai Purun) -2.522927° -

The Spatial Configuration of Private Investments by Economic Actors in Perak

The spatial configuration of private investments by economic actors in Perak A consideration of centricity of the regional urban system of Southern Perak (Peninsular Malaysia) Luka Raaijmakers (6314554) Under supervision of dr Leo van Grunsven Faculty of Geosciences Department of Human Geography and Planning Master’s degree in Economic Geography Specialisation in Regional Development & Policy November 2019 Page | 2 Acknowledgements This thesis is part of the joint research project on regional urban dynamics in Southern Perak (Peninsular Malaysia). The project is a collaboration between Utrecht University (The Netherlands) and Think City Sdn Bhd (Malaysia), under supervision of dr Leo van Grunsven and Matt Benson. I would like to thank dr Leo van Grunsven for his advice related to scientific subjects and his efforts to make us feel at home in Malaysia. Also, I would like to thank Matt Benson and Joel Goh and the other colleagues of Think City for the assistance in conducting research in – for me – uncharted territory. I would like to address other words of thanks to the Malaysian Investment Development Authority, Institut Darul Ridzuan and all other political bodies that have proven to be valuable as well as economic actors for their honesty and openness with regard to doing business in Malaysia/Perak. Finally, the fun part of writing a master’s thesis in Malaysia, apart from obviously living abroad on a vibrant island, was the part of doing research. This required a little creativity, some resilience and even more perseverance. This could not have been done without the other student members of the research team that took part in the collective effort of unravelling the urban system of Perak by using the knowledge we have gained in our years as academics. -

The Chinese Education Movement in Malaysia

INSTITUTIONS AND SOCIAL MOBILIZATION: THE CHINESE EDUCATION MOVEMENT IN MALAYSIA ANG MING CHEE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2011 i 2011 ANG MING CHEE CHEE ANG MING SOCIAL MOBILIZATION:SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS AND THE CHINESE EDUCATION CHINESE MOVEMENT INTHE MALAYSIA ii INSTITUTIONS AND SOCIAL MOBILIZATION: THE CHINESE EDUCATION MOVEMENT IN MALAYSIA ANG MING CHEE (MASTER OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, UPPSALA UNIVERSITET, SWEDEN) (BACHELOR OF COMMUNICATION (HONOURS), UNIVERSITI SAINS MALAYSIA) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2011 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My utmost gratitude goes first and foremost to my supervisor, Associate Professor Jamie Seth Davidson, for his enduring support that has helped me overcome many challenges during my candidacy. His critical supervision and brilliant suggestions have helped me to mature in my academic thinking and writing skills. Most importantly, his understanding of my medical condition and readiness to lend a hand warmed my heart beyond words. I also thank my thesis committee members, Associate Professor Hussin Mutalib and Associate Professor Goh Beng Lan for their valuable feedback on my thesis drafts. I would like to thank the National University of Singapore for providing the research scholarship that enabled me to concentrate on my thesis as a full-time doctorate student in the past four years. In particular, I would also like to thank the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences for partially supporting my fieldwork expenses and the Faculty Research Cluster for allocating the precious working space. My appreciation also goes to members of my department, especially the administrative staff, for their patience and attentive assistance in facilitating various secretarial works. -

The Journal of Social Sciences Research ISSN(E): 2411-9458, ISSN(P): 2413-6670 Special Issue

The Journal of Social Sciences Research ISSN(e): 2411-9458, ISSN(p): 2413-6670 Special Issue. 6, pp: 852-860, 2018 Academic Research Publishing URL: https://arpgweb.com/journal/journal/7/special_issue Group DOI: https://doi.org/10.32861/jssr.spi6.852.860 Original Research Open Access Preserving and Conserving Malay Royal Towns Identity in Malaysia Sharyzee Mohmad Shukri * Infrastructure University Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Golnoosh Manteghi Infrastructure University Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Mohammad Hussaini Wahab Razak School of Engineering & Advanced Technology, Universiti Teknologi, Malaysia Rohayah Che Amat St Razak School of Engineering & Advanced Technology, Universiti Teknologi, Malaysia Wong Hick Ming Infrastructure University Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Abstract Malay Royal towns in Malaysia are the best evolution examples of Malay towns dating from the 16th century which have a strong related history of old Malay Kingdom that are worthy of preservation. This paper aims to discover the significance of the royal towns so as to ensure its preservation. This research managed to identify the townscape characteristics that shaped the identity of Malay Royal towns in Malaysia. Based on the historical and physical evidences that are still exist, five (5) royal towns that gazated will be selected as study area namely; Anak Bukit (Alor Setar), Klang, Sri Menanti, Kuala Terengganu and Kota Bharu. This study utilized a series of qualitative approaches that included literature reviews of scholarly articles, historical map overlay, semi-structured interviews and site observations. The findings from this research expose that Malay Royal towns have a great significant in the development of Malay towns in Malaysia. These towns also reveal a few of townscape characteristics that are associate as an urban heritage, rich with identity, cultural and architectural significance. -

Bukit Puteri- RSPO 4Th ASA Report 12102015

Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil 4th Annual Surveillance Audit Report Report no.: ASA 4 _824 502 14020 Surveillance assessment against the RSPO Principles & Criteria NI Malaysia year 2014 Sime Darby Plantation Sdn. Bhd. SOU 10 Bukit Puteri Palm Oil Mill Level 3A, Main Block, Plantation Tower, No 2, Jalan PJU 1A/7, Ara Damansara, 47301 Petaling Jaya, Selangor Darul Ehsan,Malaysia. Date of assessment: 27-29 April 2015 Report prepared by: Carol Ng Siew Theng (RSPO Lead Auditor) Certification Body: PT TUV Rheinland Indonesia Menara Karya, 10 th Floor Jl. H.R. Rasuna Said Block X-5 Kav.1-2 Jakarta 12950,Indonesia Tel: +62 21 57944579 Fax: +62 21 57944575 www.tuv.com/id TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 SCOPE OF ANNUAL SURVEILLANCE AUDIT 3 1.1 National Interpretation Used 3 1.2 Type of Assessment 3 1.3 Certification Details 3 1.4 Location and Maps 4 1.5 Organisational Information / Contact Person 5 1.6 Description of Supply Base 5 1.7 Actual production volumes, tonnages and projected outputs. 6 1.8 Dates of Plantings and Replanting Cycles 6 1.9 Area of Plantation (Total, Planted and Mature) 7 1.10 Progress Against Time Bound Plan 7 1.11 Compliance to Rules for Partial Certification 8 1.12 Progress of associated smallholders or outgrowers towards RSPO compliance 10 1.13 Approximate Tonnages Certified 10 2.0 ASSESSMENT PROCESS 11 2.1 Certification Body 11 2.2 Qualifications of Lead Assessor and Assessment Team 11 2.3 Assessment Methodology & Agenda 12 3.0 ASSESSMENT FINDINGS 14 3.1 Summary of Findings 14 3.2 Status of Previously Identified Non-conformities -

Legibility Pattern at a City Centre of Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia

©2020 International Transaction Journal of Engineering, Management, & Applied Sciences & Technologies International Transaction Journal of Engineering, Management, & Applied Sciences & Technologies http://TuEngr.com PAPER ID: 11A11I LEGIBILITY PATTERN AT A CITY CENTRE OF KUALA TERENGGANU, MALAYSIA 1 1 Ahmad Syamil Sazali , Ahmad Sanusi Hassan , 1* 2 Yasser Arab , Boonsap Witchayangkoon 1 School of Housing, Building & Planning, Universiti Sains Malaysia, MALAYSIA. 2 Department of Civil Engineering, Thammasat School of Engineering, Thammasat University, THAILAND. A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T RA C T Article history: This paper seeks to determine five elements of the urban design Received 14 May 2019 Received in revised form 01 that can be analysed in Kuala Terengganu City Centre to form a clear April 2020 mental map of the urban environment and planning strategies by the Accepted 04 May 2020 government of Terengganu. A comprehensive urban trail conducted Available online 19 May 2020 focusing on the city centre to study the urbanism elements and planning Keywords: strategies by the government of Kuala Terengganu. Urban planning and Coastal heritage city; community building ideas towards a better city have been taking into Urban Planning; Urban city design; City zoning; considerations by the authority of Kuala Terengganu in presenting the Mental map; Malay town; ideas of Coastal Heritage City. The strategic and pragmatic urban City identify. design approaches by the government of Terengganu by indicating the specific zoning within the city centre itself have indirectly strengthened the city development identity. The outcomes of this study prove that urban design elements play an essential role in creating a specific mental mapping in persona picturesque about Kuala Terengganu City Centre. -

Kuala Terengganu

Kuala Terengganu As the state and royal capital of Terengganu, Kuala Terengganu is a riverine city strategically located in the estuary of the Terengganu River. In the old days Kuala Terengganu used to be a busy port of call for traders, missionaries, scholars and sailors from the neighbouring region as well as from other parts of the world. As a waterfront city with a tinge of traditional infrastructures, Kuala Terengganu is set to become a hub for tourism as well as a corridor for investors. Kuala Terengganu has an abundance of appeals and attractions, offering glimpses of a unique blend of local tradition, rich cultures, heritage and the beauty of nature, plus the warmth of its people, all together in the developing city of Kuala Terengganu. Beautiful State, Beautiful Culture Taman Tamadun Islam (Islamic Civilization Park) Noor Arfa Craft Complex Bukit Puteri Istana Maziah Traditional Boat Making China Town Kota Lama Duyong River Cruise Activity Terengganu State Museum Floating Mosque (Tengku Tengah Zaharah Mosque) Crystal Mosque Pasar Payang 4 KUALA TERENGGANU WATERFRONT HERITAGE CITY 5 PASAR PAYANG How to get there The popular Payang Central Market, located by Pasar Payang is located in the the Terengganu River is a perennial crowd-puller centre of the city, within the vicinity of Dataran Shahbandar that provides a colourful snapshot of the amalgam and Chinatown, overlooking the of faiths and cultures found in Terengganu. It is Terengganu River. It is easy to get to one of the most popular tourist spots in Kuala from wherever you might be staying. Terengganu. 6 KUALA TERENGGANU The wet market offers a variety of fresh from the sea products, meat, chicken, vegetables, spices, herbs, fruits and daily household items.