Proquestdocuments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Link to PDF Version

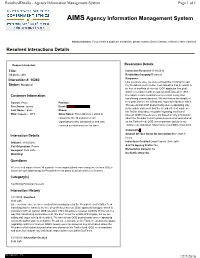

ResolvedDetails - Agency Information Management System Page 1 of 1 AIMS Agency Information Management System Announcement: If you create a duplicate interaction, please contact Gwen Cannon-Jenkins to have it deleted Resolved Interactions Details Reopen Interaction Resolution Details Title: Interaction Resolved:11/30/2016 34 press calls Resolution Category:Resolved Interaction #: 10260 Response: Like everyone else, we were excited this morning to read Status: Resolved the President-elect’s twitter feed indicating that he wants to be free of conflicts of interest. OGE applauds that goal, which is consistent with an opinion OGE issued in 1983. Customer Information Divestiture resolves conflicts of interest in a way that transferring control does not. We don’t know the details of Source: Press Position: their plan, but we are willing and eager to help them with it. The tweets that OGE posted today were responding only First Name: James Email: (b)(6) ' to the public statement that the President-elect made on Last Name: Lipton Phone: his Twitter feed about his plans regarding conflicts of Title: Reporter - NYT Other Notes: This contact is a stand-in interest. OGE’s tweets were not based on any information contact for the 34 separate news about the President-elect’s plans beyond what was shared organizations who contacted us and who on his Twitter feed. OGE is non-partisan and does not received our statement on the issue. endorse any individual. https://twitter.com/OfficeGovEthics Complexity( Amount Of Time Spent On Interaction:More than 8 Interaction Details hours Initiated: 11/30/2016 Individuals Credited:Leigh Francis, Seth Jaffe Call Origination: Phone Add To Agency Profile: No Assigned: Seth Jaffe Memorialize Content: No Watching: Do Not Destroy: No Questions We received inquires from 34 separate news organizations concerning tweets from OGE's twitter account addressing the President-elect's plans to avoid conflicts of interest. -

RAO BULLETIN 15 December 2017

RAO BULLETIN 15 December 2017 PDF Edition THIS RETIREE ACTIVITIES OFFICE BULLETIN CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES Pg Article Subject . * DOD * . 04 == DoD Cluster Bomb Policy ---- (2019 Use Deadline Set Aside 05 == Pentagon Accounting [02] ---- (44,000 Troops Unaccounted For) 05 == Transgender Lawsuits [03] ---- (Trump Files Appeal to Delay Enlistments) 06 == DoD Fraud, Waste, & Abuse ---- (Reported 01 thru 15 DEC 2017) 06 == POW/MIA [95] ---- (100 Oklahoma Sailors Identified So Far) 09 == POW/MIA [96] ---- (PFC Albert Strange) 10 == POW/MIA Recoveries ---- (Reported 01 thru 15 DEC 2017 | Twelve) . * VA * . 12 == VA Health Care Enrollment [14] ---- (Its For Life) 12 == VA AIDS Care [08] ---- (Have You Taken the Test?) 13 == VADIP [05] ---- (Dental Program Revived & Extended Through 2021) 13 == GI Bill [244] ---- (Forever GI Bill Implementation) 15 == VA DRC Program ---- (Latest Enhancements to Expand Participants) 15 == VA TRICARE Merger ---- (A Controversial Issue| Pros & Cons) 18 == Traumatic Brain Injury [65]---- (VA Offering LED & SGB Treatments) 18 == VA HUD-VASH [05] ---- (No Change In Funding Until Fiscal 2019) 19 == VA Compensation Rates | Disability ---- (2018 Monthly Payments) 20 == VDHCBS [01] ---- (Gives Disabled Vets Ability to Control Their Own Care) 21 == Fisher House Expansion [19] ---- (Charleston SC Opens) 22 == ALS [13] ---- (Radicava Added to VANF for Vet Treatment) 1 23 == VA ID Card [14] ---- (Applications Suspended | System Overloaded) 24 == VA Nurse Anesthetists ---- (Underutilized) 25 == VA Caregiver Program [47] ---- (Petition Delivered to Congress) 25 == VA Loans ---- (Warno | Unsolicited Offers) 27 == VA Fraud, Waste & Abuse ---- (Reported 01 thru 15 DEC 2017) 32 == VA Compensation & Benefits ---- (Problem Solving Program Q&A -- 23 Correction) . * VETS * . 33 == Homeless Vets [82] ---- (First Increase in 7 Years) 34 == Missouri Veteran Homes [02] ---- (St. -

Iaj 10-4 (2019)

Vol. 10 No. 4 2019 Arthur D. Simons Center for Interagency Cooperation, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas FEATURES | 1 About The Simons Center The Arthur D. Simons Center for Interagency Cooperation is a major program of the Command and General Staff College Foundation, Inc. The Simons Center is committed to the development of military leaders with interagency operational skills and an interagency body of knowledge that facilitates broader and more effective cooperation and policy implementation. About the CGSC Foundation The Command and General Staff College Foundation, Inc., was established on December 28, 2005 as a tax-exempt, non-profit educational foundation that provides resources and support to the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College in the development of tomorrow’s military leaders. The CGSC Foundation helps to advance the profession of military art and science by promoting the welfare and enhancing the prestigious educational programs of the CGSC. The CGSC Foundation supports the College’s many areas of focus by providing financial and research support for major programs such as the Simons Center, symposia, conferences, and lectures, as well as funding and organizing community outreach activities that help connect the American public to their Army. All Simons Center works are published by the “CGSC Foundation Press.” The CGSC Foundation is an equal opportunity provider. InterAgency Journal Vol. 10, No. 4 (2019) FEATURES Arthur D. Simons Center 5 The Economics of Trade and National Security for Interagency Cooperation David A. Anderson The Lewis and Clark Center 100 Stimson Ave., Suite 1149 14 Enabling Tax Payments: A Novel Approach to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 66027 Ph: 913-682-7244 • Fax: 913-682-7247 Reducing Violence and Poverty in El Salvador Email: [email protected] Ann Low www.TheSimonsCenter.org 26 Very Small Satellites: A Mechanism for EDITOR-IN-CHIEF the Early Detection of Mass Atrocities Roderick M. -

THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Law.Adelaide.Edu.Au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD

Volume 40, Number 2 THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW law.adelaide.edu.au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD The Honourable Professor Catherine Branson AC QC Deputy Chancellor, The University of Adelaide; Former President, Australian Human Rights Commission; Former Justice, Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor William R Cornish CMG QC Emeritus Herchel Smith Professor of Intellectual Property Law, University of Cambridge His Excellency Judge James R Crawford AC SC International Court of Justice The Honourable Professor John J Doyle AC QC Former Chief Justice, Supreme Court of South Australia Professor John V Orth William Rand Kenan Jr Professor of Law, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Professor Emerita Rosemary J Owens AO Former Dean, Adelaide Law School The Honourable Justice Melissa Perry Federal Court of Australia The Honourable Margaret White AO Former Justice, Supreme Court of Queensland Professor John M Williams Dame Roma Mitchell Chair of Law and Former Dean, Adelaide Law School ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Editors Associate Professor Matthew Stubbs and Dr Michelle Lim Book Review and Comment Editor Dr Stacey Henderson Associate Editors Kyriaco Nikias and Azaara Perakath Student Editors Joshua Aikens Christian Andreotti Mitchell Brunker Peter Dalrymple Henry Materne-Smith Holly Nicholls Clare Nolan Eleanor Nolan Vincent Rocca India Short Christine Vu Kate Walsh Noel Williams Publications Officer Panita Hirunboot Volume 40 Issue 2 2019 The Adelaide Law Review is a double-blind peer reviewed journal that is published twice a year by the Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide. A guide for the submission of manuscripts is set out at the back of this issue. -

Organizational Ethics Gone Wrong

Organizational Ethics Gone Wrong by Jonathan Bailey and Ted Thomas at” Leonard Francis, owner of Glenn Defense Marine Asia and a good friend to the Navy leadership for over a decade, defrauded the U.S. Navy for $35 million dollars. The investigation that followed implicated scores of Navy personnel, including admirals, in the Fcorruption scandal. He bribed leaders and key personnel with money, prostitutes, expensive gifts, free vacations, and other things. In return for his “gifts,” he gained classified information about docking schedules and overcharged the Navy for his company’s services.1 The remarkable fact about all of this is not that it happened, but that the corruption was so rampant and almost became part of the accepted culture of the 7th fleet. With all of the fiscal oversight within government contracting and the organizational moral codes of the armed services, how could this happen? How could this many organizational leaders move from their ethical foundations and drift into unethical behavior, or even condone it by their inaction as they watched others participate in it? What causes an organization to drift from its espoused values to immoral and often criminal behaviors, and how can leaders prevent this from happening? The answers to these questions are important for organizational leaders to understand, and the answers carry significant moral and ethical implications for society.2 High profile leaders who fall from grace due to abuse of power, money, or sex issues get a lot of press—bad press. In many cases, others in the organization knew the leader was doing something Chaplain (Major) Jonathan Bailey is the Ethics Instructor at the U.S. -

Corporate Governance Case Studies Volume 7

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE CASE STUDIES VOLUME SEVEN Edited by Mak Yuen Teen Corporate Governance Case Studies Volume seven Mak Yuen Teen, PhD, FCPA (Aust.) Editor First published October 2018 Copyright ©2018 Mak Yuen Teen and CPA Australia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except for inclusion of brief quotations in a review. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, CPA Australia Ltd. Please contact CPA Australia or Professor Mak Yuen Teen for permission of use of any case studies in this publication. Corporate Governance Case Studies Volume Seven Editor : Mak Yuen Teen, PhD, FCPA (Aust.) Editor’s email : [email protected] Published by : CPA Australia Ltd 1 Raffles Place #31-01 One Raffles Place Singapore 048616 Website : cpaaustralia.com.au Email : [email protected] ISBN : 978-981-11-8936-4 II Contents Foreword Preface Singapore Cases Is Datapulse Flatlining? ................................................................................................. 1 Fat Leonard: The Elephant In The U.S. Navy’s Room .................................................. 42 A Good Deal? Privatisation Of Global Logistic Properties ........................................... 57 The Diagnosis Of Healthway ...................................................................................... -

Overview of the Annual Report on Sexual Harassment and Violence at the Military Service Academies Committee on Armed Services Ho

i [H.A.S.C. No. 115–41] OVERVIEW OF THE ANNUAL REPORT ON SEXUAL HARASSMENT AND VIOLENCE AT THE MILITARY SERVICE ACADEMIES HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON MILITARY PERSONNEL OF THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION HEARING HELD MAY 2, 2017 U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 25–834 WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 SUBCOMMITTEE ON MILITARY PERSONNEL MIKE COFFMAN, Colorado, Chairman WALTER B. JONES, North Carolina JACKIE SPEIER, California BRAD R. WENSTRUP, Ohio, Vice Chair ROBERT A. BRADY, Pennsylvania STEVE RUSSELL, Oklahoma NIKI TSONGAS, Massachusetts DON BACON, Nebraska RUBEN GALLEGO, Arizona MARTHA MCSALLY, Arizona CAROL SHEA-PORTER, New Hampshire RALPH LEE ABRAHAM, Louisiana JACKY ROSEN, Nevada TRENT KELLY, Mississippi DAN SENNOTT, Professional Staff Member CRAIG GREENE, Professional Staff Member DANIELLE STEITZ, Clerk (II) C O N T E N T S Page STATEMENTS PRESENTED BY MEMBERS OF CONGRESS Coffman, Hon. Mike, a Representative from Colorado, Chairman, Subcommit- tee on Military Personnel .................................................................................... 1 Speier, Hon. Jackie, a Representative from California, Ranking Member, Sub- committee on Military Personnel ........................................................................ 2 WITNESSES Panel -

Enhancing Professionalism in the U.S. Air Force

C O R P O R A T I O N Enhancing Professionalism in the U.S. Air Force Jennifer J. Li, Tracy C. McCausland, Lawrence M. Hanser, Andrew M. Naber, Judith Babcock LaValley For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1721 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9700-2 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Writing about the profession of arms in a February 2012 white paper, then–Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff GEN Martin Dempsey wrote, “We must continue to learn, to understand, and to promote the knowledge, skills, attributes, and behaviors that define us as a profession.”1 In January 2014, the U.S. -

Husbanding Service Provider Price Analysis Factors

NPS-CE-21-235 ACQUISITION RESEARCH PROGRAM SPONSORED REPORT SERIES Husbanding Service Provider Price Analysis Factors June 2021 LCDR Austin W. Gage, USN LCDR Luis C. Escobar, USN LCDR Bradford R. Sturgis Jr., USN Thesis Advisors: Dr. Geraldo Ferrer, Professor Dr. Robert F. Mortlock, Professor Graduate School of Defense Management Naval Postgraduate School Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Prepared for the Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA 93943. Acquisition Research Program Graduate School of Defense Management Naval Postgraduate School The research presented in this report was supported by the Acquisition Research Program of the Graduate School of Defense Management at the Naval Postgraduate School. To request defense acquisition research, to become a research sponsor, or to print additional copies of reports, please contact the Acquisition Research Program (ARP) via email, [email protected] or at 831-656-3793. Acquisition Research Program Graduate School of Defense Management Naval Postgraduate School ABSTRACT Since 2015, the Navy acquisition community has undergone significant changes to oversight policies and contracting methods for husbanding services. The changes were imposed because of one of the largest corruption scandals in U.S. Navy history. The rapid effects of these changes have not been thoroughly analyzed. In this thesis, there is data from the last 5 years totaling over 6,000 husbanding service contracts and port visits. The authors analyzed this data to determine if the current process is having an adverse financial impact, including the financial impact of short-notice port visits, contractor competition, and the length of solicitation. They used a cross-tabulation methodology to determine if short-notice port visits’ request submissions have a financial impact on the cost of husbanding services. -

The Military Industrial Complex and Us Foreign Policy – the Cases of Saudi Arabia & Uae

A MUTUAL EXTORTION RACKET: THE MILITARY INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX AND US FOREIGN POLICY – THE CASES OF SAUDI ARABIA & UAE BY JODI VITTORI, TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL DEFENSE & SECURITY PROGRAM 2. A MUTUAL EXTORTION RACKET: THE MILITARY INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX AND US FOREIGN POLICY-- THE CASES OF SAUDI ARABIA & UAE CONTENTS Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................................................................3 Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................................................................4 Cycle of Influence ................................................................................................................................................................................8 Section 1: Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................9 Section 2: The Role and Importance of the American Defense Sector: Economy, Politics, and Foreign Policy ..................................10 The Economy ..............................................................................................................................................................................10 Politics and Foreign Policy ...........................................................................................................................................................11 -

Nicholas Carlini, Florian Tramer, Eric Wallace, Matthew

Extracting Training Data from Large Language Models Nicholas Carlini, Florian Tramer, Eric Wallace, Matthew Jagielski, Ariel Herbert-Voss, Katherine Lee, Adam Roberts, Tom Brown, Dawn Song, Ulfar Erlingsson, Alina Oprea, Colin Raffel N. Carlini F. Tramèr E. Wallace M. Jagielski A. Herbert-Voss K. Lee Google Stanford Berkeley Northeastern Harvard Google A. Roberts T. Brown D. Song Ú. Erlingsson A. Oprea C. Raffel Google OpenAI Berkeley Apple Northeastern Google https://xkcd.com/2169/ Does this really, actually, happen? Does this really, actually, happen? YES, it does Act I: Extracting Training Data Language Model Our Attack: 1. Generate a lot of data 2. Predict membership alter the environment, changing weather patterns and the time of day to suit their needs. The aliens A federal appeals court on Wednesday struck down Texas' voter-ID law, which the Supreme Court had blocked last year. The ruling could potentially affect the upcoming elections in a number of states. Here's what you need to know about the ruling. (Claritza Jimenez/The Washington Post) A federal appeals court on Wednesday struck down Texas' voter-ID law, which the Supreme Court had blocked last year. The ruling could potentially affect the upcoming elections in a number of states. Here's what you need to know about the ruling. (Claritza Jimenez/The Washington Post) A federal appeals court on Wednesday struck down Texas' voter-ID law, which the Supreme Court had blocked last year. The ruling could potentially affect the upcoming elections in a number of states. Here's what you need to know about the ruling. -

Bulletin 190214 (PDF Edition)

RAO BULLETIN 14 February 2019 PDF Edition THIS RETIREE ACTIVITIES OFFICE BULLETIN CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES Pg Article Subject . * DOD * . 04 == U.S. Philippine Bases [18] ---- (New Facility Opened on Luzon) 05 == SECDEF [17] ---- (Patrick Shanahan’s International Debut) 06 == Nuclear Launch Authority [01] ---- (H.R.669/S.200 | No First Use Act) 07 == StratCom ---- (A First Look inside New $1.3 Billion Headquarters) 09 == China’s Space Program ---- (U.S. Military Warns of Their Argentina Space Station Threat) 11 == GTMO Prison [12] ---- (Option of Last Resort for ISIS Detainees) 12 == DODDS No Touching Rule ---- (New NBC Policy Questioned) 13 == PCS Moves [05] ---- (Privatizing Household Goods Shipments) 15 == DoD/VA Health Care ---- (Portions of Both Systems May Merge) 16 == DoD Fraud, Waste, & Abuse ---- (Reported 01 thru 14 FEB 2019) 18 == POW/MIA Recoveries & Burials ---- (Reported 01 thru 14 FEB 2019 | Seven) 20 == DoD Websites [01] ---- (Watch Out for Fake Ones) . * VA * . 20 == VA Access via ID.me ---- (New Option Brings Virtual Identity Proofing to the VA) 22 == VA Blue Water Claims [64] ---- (Court Ruling Fuels Renewed Effort for Bill) 23 == VA Blue Water Claims [65] ---- (Now is the Time to File VA Form 21-0966) 1 23 == VA Disability Rating [02] ---- (How To Increase Your Percentage) 25 == VA Disciplinary Actions [02] ---- (Vet Indicted for Making Threats and Assault) 25 == VA Shadow Rulers ---- (HVAC Investigation Launching on Trump’s Golf Buddies) 26 == VA Lawsuit | Caregiver Program ---- (Laws & Regulations Not Followed by VA) 27 == VA 3D Printing ---- (Use is Lowering Costs, and Reducing Surgery/Healing) 28 == Twilight Brigade ---- (VA Evicting Group after 21 Years at the Bedsides of Dying Patients) 30 == VA Appeals [34] ---- (Appeals Modernization Act Now In Effect) 31 == VA Health Care Access [64] ---- (Fight over Privatization to Escalate) 33 == VA Fraud, Waste & Abuse ---- (Reported 01 thru 14 FEB 2019) .