Kirksville Daily Express - Tuesday, August 6, 1912

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Border Star

The Border Star Official Publication of the Civil War Round Table of Western Missouri “Studying the Border War and Beyond” April 2011 The bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861 was the The Civil War Round Table Cwas was e opening engagement of the American Civil War. The 150th Anofnive Westernrsary onMissouri April 12, Anniversary of the American Civil War is upon us! ………………………………………………………………………………................. 2011 Officers President --------------- Mike Calvert 1st V.P. -------------------- Pat Gradwohl 2nd V.P. ------------------- Art Kelley President’s Letter Secretary ---------------- Karen Wells Treasurer ---------------- Beverly Shaw Many years ago when I was just a lowly freshman at the University of Missouri, Historian ------------------ Open Rolla there was a road sign just as you made the turn onto Pine Street (the main Board Members street) that read “Rolla Missouri, the Watch Me City of the Show Me State” Delbert Coin Karen Coin Little did I know that that same sign could have describe Rolla in 1861. At the Terry Chronister Barbara Hughes terminus of the St Louis-San Francisco Railroad, Rolla was a strategic depot for Don Moorehead Kathy Moorehead all the campaigns into southwest Missouri to follow. Seized by Franz Siegel for Steve Olson Carol Olson Liz Murphy Terry McConnell the Union on June 14, 1861 it remained in Union hands throughout the war. So important as a supply depot that two forts were built to protect it (Fort Wyman The Border Star Editor and Fort Dettec). 20,000 troops were stationed there under orders from President Dennis Myers Lincoln to hold it at all costs. Phil Sheridan was stationed there as a Captain in 12800 E. -

Historical Review

HISTORICAL REVIEW APRIL 1963 Fred Geary's "The Steamboat Idlewild' Published Quarterly By The State Historical Society of Missouri COLUMBIA, MISSOURI THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI The State Historical Society of Missouri, heretofore organized under the laws of this State, shall be the trustee of this State—Laws of Missouri, 1899, R. S. of Mo., 1949, Chapter 183. OFFICERS 1962-65 ROY D. WILLIAMS, Boonville, President L. E. MEADOR, Springfield, First Vice President LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville, Second Vice President WILLIAM L. BRADSHAW, Columbia, Third Vice President RUSSELL V. DYE, Liberty, Fourth Vice President WILLIAM C TUCKER, Warrensburg, Fifth Vice President JOHN A. WINKLER, Hannibal, Sixth Vice President R. B. PRICE, Columbia, Treasurer FLOYD C SHOEMAKER, Columbia, Sacretary Emeritus and Consultant RICHARD S. BROWNLEE, Columbia, Director, Secretary, and Librarian TRUSTEES Permanent Trustees, Former Presidents of the Society E. L. DALE, Carthage E. E. SWAIN, Kirksville RUSH H. LIMBAUGH, Cape Girardeau L. M. WHITE, Mexico GEORGE A. ROZIER, Jefferson City Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1963 RALPH P. BIEBER, St. Louis LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville BARTLETT BODER, St. Joseph W. WALLACE SMITH, Independence L. E. MEADOR, Springfield JACK STAPLETON, Stanberry JOSEPH H. MOORE, Charleston HENRY C THOMPSON, Bonne Terre Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1964 WILLIAM R. DENSLOW, Trenton FRANK LUTHER MOTT, Columbia ALFRED O. FUERBRINGER, St. Louis GEORGE H. SCRUTON, Sedalia GEORGE FULLER GREEN, Kansas City JAMES TODD, Moberly ROBERT S. GREEN, Mexico T. BALLARD WATTERS, Marshfield Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1965 FRANK C BARNHILL, Marshall W. C HEWITT, Shelbyville FRANK P. BRIGGS, Macon ROBERT NAGEL JONES, St. -

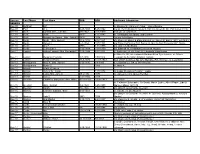

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P. m. Eleanor R. Clark 5-21-1866; stone illegible Bee-09 Purl J. C. 8-25-1898 5-25-1902 s/o Dr. Henry Bosworth & Laura Purl; b/o Aileen B. (Dr. Purl buried in CA) Bee-10 Buck Cynthia (Mrs. John #2) 2-6-1842 11-6-1930 2nd wife of John Buck Bee-10 Buck John 1807 3-25-1887 m.1st-Magdalena Spring; 2nd-Cynthia Bee-10 Buck Magdalena Spring (Mrs. John #1) 1805 1874 1st w/o John Buck Bee-10 Burris Ida B. (Mrs. James) 11-6-1858 2/12/1927 d/o Moses D. Burch & Efamia Beach; m. James R. Burris 1881; m/o Ora F. Bee-10 Burris James I. 5-7-1854 11/8/1921 s/o Robert & Pauline Rich Burris; m. Ida; f/o Son-Professor O.F. Burris Bee-10 Burris Ora F. 1886 2-11-1975 s/o James & Ida Burris Bee-10 Burris Zelma Ethel 7-15-1894 1-18-1959 d/o Elkanah W. & Mahala Ellen Smith Howard Bee-11 Lamkin Althea Leonard (Mrs. Benjamin F.) 7-15-1844 3/17/1931 b. Anderson, IN; d/o Samuel & Amanda Eads Brown b. Ohio Co, IN ; s/o Judson & Barbara Ellen Dyer Lamkin; m. Althea Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Franklin 1-7-1836 1/30/1914 Leonard; f/o Benjamin Franklin Lamkin Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Frank 11-9-1875 12-17-1943 Son of B.F. & Althea; Sp. Am. War Mo., Pvt. -

Missouri Historical Revi Ew

MISSOURI HISTORICAL REVI EW. CONTENTS George Engelmann, Man of Science William G. Bek The National Old Trails Road at Lexington B. M. Little The Blairs and Fremont William E. Smith An Early Missouri Political Fend Roy V, Magers The Great Seal of the State of Missouri Perry S. Rader Historical Notes and Comments Missouri History Not Found in Textbooks STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY of MISSOURI VOL. XXIII JANUARY, 1929 NO. 2 OFFICERS OF THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI, 1925-1928 GEORGE A. MAHAN, Hannibal, President. LOUIS T. GOLDING, St. Joseph, First Vice-President. WALTER B. STEVENS, St. Louis, Second Vice-President. WALTER S. DICKEY, Kansas City, Third Vice-President. CORNELIUS ROACH, Kansas City, Fourth Vice-President. E. N. HOPKINS, Lexington, Fifth Vice-President. ALLEN McREYNOLDS, Carthage, Sixth Vice-President. R. B. PRICE, Columbia, Treasurer. FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER, Secretary and Librarian. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1928 ROLLIN J. BRITTON, Kansas ISIDOR LOEB, St. Louis. City. C. H. McCLURE Kirksville. T. H. B. DUNNEGAN, Bolivar. JOHN ROTHENSTEINER, BEN L. EMMONS, St. Charles. St. Louis. STEPHEN B. HUNTER, CHAS. H. WHITAKER, Cape Girardeau. Clinton. Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1929 PHIL A. BENNETT, Springfield. J. F. HULL, Maryville. JOSEPH A. CORBY, St. Joseph. ELMER O. JONES, LaPlata. W. E. CROWE, DeSoto. WM. SOUTHERN, JR. FORREST C. DONNELL, Independence. St. Louis. CHARLES L. WOODS, Rolla. BOYD DUDLEY, Gallatin. Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1930 C. P. DORSEY, Cameron. H. S. STURGIS, Neosho. EUGENE FAIR, Kirksville. JONAS VILES, Columbia. THEODORE GARY, Kansas City. R. M. WHITE, Mexico. GEORGE A. MAHAN, Hannibal. -

Collection Created by Dr. George C. Rable

Author Surname Beginning with “P” Collection created by Dr. George C. Rable Documents added as of September 2021 Power, Ellen Louise. “Excerpts from the Diary of Ellen Louise Power.” United Daughters of the Confederacy Magazine 11 (December 1948): 10-11. West Feliciana, Louisiana, plantation Arrival of Confederate cavalry, 10 Fighting at Clinton, 10-11 Port Hudson, 11 Yankees search house, destruction, 11 Corinth, 11 Jackson, fear of Yankees and possible burning, 11 Park, Andrew. “Some Recollections of the Battle of Gettysburg.” Civil War Times 44 (August 2005): electronic, no pagination. 42nd Mississippi Infantry, Co. I Arkansas History Commission and Archives Gettysburg, July 1 Wheat field Recrossing the Potomac Parsons, William H. “’The World Never Witnessed Such Sights.” Edkted by Bryce Suderow. Civil War Times Illustrated 24 (September 1985): 20-25. 12th Texas Cavalry, Colonel Report on Red River campaign, 20ff Blair’s Landing Pleasant Hill, 21 Grand Ecore, Banks retreat, 21 Natchitoches, 22 Cloutiersville, 23 Casualties, 25 Pehrson, Immanuel C. “A Lancaster Schoolboy Views the Civil War.” Edited by Elizabeth C. Kieffer. Lancaster County Historical Society Papers 54 (1950): 17-37. Lancaster Pennsylvania, 14 year old schoolboy Peninsula campaign, Williamsburg, 20 2 Baltimore riot, 21 Lincoln calls for 300,000 more troops, 23 Playing cricket, 26 Election excitement, 1862, 30 Christmas, 33 Letter from Lincoln, 34 Copperheads, 36 Pelham, Charles and John Pelham. “The Gallant Pelhams and Their Abolitionist Kin.” Civil War Times 42 (October 2003): electronic, no pagination. Lincoln’s election Southern independence Slavery Abolitionist aunt Fort Morgan West Point Death of John Pelham Pennington, George W. “Letters and Diaries.” Civil War Times Illustrated 1 (October 1962): 40-41. -

The Missouri Historical Review .•

THE MISSOURI HISTORICAL REVIEW .• ' : VOLUME IX JULY, 1915 NUMBER 4 mm? TABLE OF CONTENTS Six Periods of Missouri History Page FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER 221 "Missouri Day" Programs for ;~j Missouri Club Women.... 241 Historical Articles in Missouri Newspapers 248 Notes and Documents 263 Historical News and Comments 272 Published Quarterly by THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI COLUMBIA • . ' C Entered as second-class mail matter at Columbia, Missouri, July 18, 1907 THE MISSOURI HISTORICAL REVIEW FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER, Editor Subscription Price-#i.oo a Year The Missouri Historical Review Is a quarterly magazine de voted to Missouri history, genealogy and literature. It is now being sent to a thousand members of the Society. The subscrip tion price is one dollar a year. The contents of each number are not protected by copyright, and speakers, editors and writers are invited to make use of the articles. Each number of the Review contains several articles on Mis souri and Missourians. These articles are the result of research work in Missouri history. They treat of subjects that lovers of Missouri are interested in. They are full of new information and are not hackneyed or trite. The style of presentation is as popular as is permissible in a publication of this character. In addition to the monographs, the Review contains a list of books recently published by Missourians or on Missouri, and a list of Missouri historical articles that have appeared in the news papers of the State. The last is an aid to teachers, editors and writers, and will become even more valuable with age. -

Genealogy of the Wisdom Family, 1675 to 1910

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/genealogyofwisdoOOwisd PHOTO BY HA2ELTINE STUDIO, BAKER, OREGON. 1890 GENEALOGY ofthe WISDOM FAMILY 1675 to 1910 \ \ '..>'> ^'' "•"*> ^vo^ ->i ' ' "," ' ' 1 ," ' • I -^ ^"'' '';'"^ • '''^,1 %- « 4 » 'W. ' ^^" Compiled by GEORGE W. WISDOM t-Great-Grandson of (4) Francis Torrence Wi and Son of (239) Thomas Barnes Wisdom > • • • •• • • • • • • • » • • • • • a • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • « • • > • • • • •• • • • > • • •• • • > • • • • • • • • • • 9 • • • • • • CONTENTS PAGE Portrait of Compiler Frontispiece Preface v Prelude vii Memorial {poem ) . xii Introduction xiii The Sunny Hours of Childhood {poem) i8 Abner Wisdom ( i ) 1675 19 Thanksgiving 20 Brinsley Mortimer Wisdom (2) Branch 23 Veteran of California Column 31 The "Savior" of Rome 32 Facsimile Letter (1853 ) 49-50 Poem 54 Pollard William Wisdom (3) Branch 57 Letter from W. W. Wisdom (81 ) 59 James M. Wisdom's (72) Family 64 Andrew Jackson Wisdom (74) 70 Francis Torrence Wisdom (4) Branch 77 Paducah's Only Millionaire 84 Letter from John Randolph Wisdom (379) .... 115 John R. Wisdom (379) Passed Away 116 A Story of the Early 6o's 124 Vesper Wisdom (414) 135 Obituary—M. D. Wisdom (400) 140 Aviator's Death—Everett Stanton Wisdom (433). 142 From Earth to Heaven (461) Nora B. Shanklin. 150 Crossing the Plains in the Early Days 176a Abner Wisdom, Jr. (5) Branch 179 Letter from W. J. V^isdom (650) 183 Letter from Thomas Wisdom (697) 197 Tavner Wisdom (6) Branch 205 Index 221 Explanation and Chart 229 Blank for Record of Lineage 2^1 P 9 7 *> a PREFACE The compilation of this work was begun March 9, 1890. -

Cultural Resource Survey Plan: a Framework for Historic Resource Survey in Kirksville

CULTURAL RESOURCE SURVEY PLAN: A FRAMEWORK FOR HISTORIC RESOURCE SURVEY IN KIRKSVILLE Prepared for THE CITY OF KIRKSVILLE By PRESERVATION SOLUTIONS LLC 09 February 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Preface : Benefits of Preservation ................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 6 Survey Plan Objectives ................................................................................................................................ 7 Survey Plan Project Area ............................................................................................................................. 8 Project History and Methodology ................................................................................................................ 10 Survey Considerations What is a Cultural Resource Survey? ............................................................................................ 14 Where to Begin .............................................................................................................................. 16 Standards and Guidelines .............................................................................................................. 22 Criteria and -

Arkansas Infantry Regiment (Lemoyne’S Sharpshooters) Formed in the St Francis County, AR Area

Charles Henry Havens October 22, 1844 – June 30, 1914 History By Henry T. Haven, Jr. 1943- Great-Grandson January 21, 2010 In the following, I will attempt to give the history of Charles Henry Havens and will note if my statements are fact, family lore, or conjecture. The Civil War Records are from Broadfoot Publishing Co. and the linage history is from Ancestory.com, a venture of the Mormon Church. The Mormon Church, or Jesus Christ Church of the Latter Day Saints, attempts to gather all historical records of linage to prove connection back to Christ. Other internet records are from on-line searches of the web. This compilation would not have been possible without the internet and the rich historical records that have been published on line. Though much of what has been written may be considered to be true, there remains a lot of conflict and questions as to verification of the data. So please read this with a skeptical viewpoint, knowing that this incomplete history could be rewritten with any new additional changes. Such are the issues in the explosion of data that is now available and found using our home computers. I wish to acknowledge the help of Paul Vernon “PV” Isbell in this research. His Grandmother was Emma Haven Hodges, a sister to Louis Franklin Haven and Daughter of Charles Henry Havens. Henry T. Haven, Jr. GERMANY EMMIGRATION: 1844-1859 Dietrich Harms, April 30, 1804-Nov 4, 1877, was born in Hanover, GER and died in Concordia, MO. His second child was, Charles Henry Harms Oct 22, 1844–Jun 30, 1914. -

The Missouri Historical Review

TheMISSOURI HISTORICAL REVIEW. CONTENTS The Liberal Republican Movement in Missouri Thomas S. Barclay Mark Twain Memorials in Hannibal Franklin It. Poage Early Gunpowder Making in Missouri \ William Clark Breckenridge The Osage War, 1837 Roy Godsey ; The Warrensburg Speech of Frank P. Blair Huston Crittenden The Story of an Ozark Feud j A. M. Haswell Personal Recollections of Distinguished Missourians— Sterling Price Daniel M. Grissom Little Visits with Literary Missourians—Rupert Hughes Catharine Cranmer Historical Notes and Comments Missouri History Not Found in Textbooks Historical Articles in Missouri Newspapers Published Quarterly by The STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY of MISSOURI Columbia VOL. XX OCTOBER, 1925 NO. 1 THE MISSOURI HISTORICAL REVIEW VOL. XX OCTOBER, 1925 NO. 1 CONTENTS The Liberal Republican Movement in Missouri 3 THOMAS S. BARCLAY Mark Twain Memorials in Hannibal 79 FRANKLIN R. POAGE Early Gunpowder Making in Missouri 85 WILLIAM CLARK BRECKENRIDGE The Osage War, 1837 96 ROT GODBEY The Warrensburg Speech of Frank P. Blair 101 HUSTON CRITTENDEN The Story of an Ozark Feud 105 A. M. HASWELL Personal Recollections of Distinguished Missourians—Sterling Price 110 DANIEL M. GRISSOM Little Visits with Literary Missourians—Rupert Hughes 112 CATHARINE CRANMER Historical Notes and Comments 120 Missouri History Not Found in Textbooks 148 Historical Articles in Missouri Newspapers 163 FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER, Editor The Missouri Historical Review is published quarterly. The sub scription price is $1.00 a year. A complete set of the REVIEW is still obtainable—Vols. 1-19, bound, $57.00; unbound, $26.00. Prices of separate volumes given on request. All communications should be addressed to Floyd C. -

The Missouri Collection (C3982)

The Missouri Collection (C3982) Collection Number: C3982 Collection Title: The Missouri Collection Dates: 1771-2021 Creator: State Historical Society of Missouri, collector Abstract: The Missouri Collection is an artificial collection combining miscellaneous small acquisitions related to Missouri places, individuals, organizations, and events. Collection Size: 18.2 cubic feet, 26 oversize items, 9 audio cassettes, 7 audio discs, 9 CDs, 1 computer disc, 1 film, 6 film strips, 5 DVDs, 2 video cassettes (821 folders, 816 photographs) Language: Collection materials are mostly in English. Some documents written in German are included. Repository: The State Historical Society of Missouri Restrictions on Access: Collection is open for research. This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Columbia. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Collections may be viewed at any research center. Restrictions on Use: Materials in this collection may be protected by copyrights and other rights. See Rights & Reproductions on the Society’s website for more information about reproductions and permission to publish. Preferred Citation: [Specific item; box number; folder number] The Missouri Collection (C3982); The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Columbia [after first mention may be abbreviated to SHSMO-Columbia]. Donor Information: The collection was donated by numerous donors over the years. Consult the reference staff for donor information for particular folders or items. Accruals: The Missouri Collection continues to grow as small collections are acquired by the State Historical Society of Missouri. New materials are placed at the end. (C3982) The Missouri Collection Page 2 Processed by: Processed by Kathleen Conway in 2002. -

Missouri Historical Review

VOL. IX. JANUARY, 1915. NO. 2. MISSOURI HISTORICAL REVIEW. PUBLISHED BY THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI. F. A. SAMPSON. Secretary, Editor. SUBSCRIPTION PRICE $1.00 PER YEAR. ISSUED QUARTERLY. COLUMBIA, MISSOURI. ENTERED AS SECOND CLASS MAIL. MATTER AT COLUMBIA, MO., JULY 18, 1907. [ISSOURI HISTORICAL REVIEW. EDITOK FRANCIS A. SAMPSON. Committee on Publication: JONAS VILES, ISIDOR LOEK, F. A. SAMPSON. VOL IX. JANUARY, \m. NO. 2. CONTENTS. Garland Carr Broadhead, by Darling K. Greger - - 57 The Cabell Descendants in Missouri, by Joseph A. Mudd 75 Books of Early Travel in Missouri—Long-James—F. A. Sampson - - - - - - - - 94 Harmony Mission and Methodist Missions, by G. C. Broadhead - - - - - - - - 102 Carroll County Marriage Record, 1833-1852, by Mary G. Brown - - - -. - . - - - 104 Notes - 132 Missouri River Boats in 1841 - - - - - 133 Book Notices - - ... .. 135 Necrology - - • - - - . - - -, 136 GARLAND CARR BROADHEAD. MISSOURI HISTORICAL REVIEW. VOL. IX. JANUARY, 1915. No. 2. GARLAND CARR BROADHEAD. Garland Can* Broadhead was born October 30, 1827, near Charlottesville, Albermarle County, Virginia. His father, Achilles Broadhead, emigrated to Missouri in 1836, and settled at Flint Hill, St. Charles County. Educated at home and in private schools, his fondness for the natural sciences, history and mathematics, early in life shaped his sphere of labor. He entered the University of Missouri in 1850, a pro ficient scholar in History, Latin and Mathematics. With the close of the school year of 1850-51 he shifted to the Western Military Academy of Kentucky, where he continued his studies in Geology, Mathematics and Engineering under the able guidance of Richard Owen, Professor of Geology and Chemistry, and General Bushrod R.