The American Indian As Participant in the Civil War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Review

HISTORICAL REVIEW OCTOBER 1961 Death of General Lyon, Battle of Wilson's Creek Published Quarte e State Historical Society of Missouri COLUMBIA, MISSOURI THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI The State Historical Society of Missouri, heretofore organized under the laws of this State, shall be the trustee of this State—Laws of Missouri, 1899, R. S. of Mo., 1949, Chapter 183. OFFICERS 1959-1962 E. L. DALE, Carthage, President L. E. MEADOR, Springfield, First Vice President WILLIAM L. BKADSHAW, Columbia, Second Vice President GEORGE W. SOMERVILLE, Chillicothe, Third Vice President RUSSELL V. DYE, Liberty, Fourth Vice President WILLIAM C. TUCKER, Warrensburg, Fifth Vice President JOHN A. WINKLER, Hannibal, Sixth Vice President R. B. PRICE, Columbia, Treasurer FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER, Columbia, Secretary Emeritus and Consultant RICHARD S. BROWNLEE, Columbia, Director. Secretary, and Librarian TRUSTEES Permanent Trustees, Former Presidents of the Society RUSH H. LIMBAUGH, Cape Girardeau E. E. SWAIN, Kirksville GEORGE A. ROZIER, Jefferson City L. M. WHITE, Mexico G. L. ZWICK. St Joseph Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1961 WILLIAM R. DENSLOW, Trenton FRANK LUTHER MOTT, Columbia ALFRED 0. FUERBRINGER, St. Louis GEORGE H. SCRUTON, Sedalia GEORGE FULLER GREEN, Kansas City JAMES TODD, Moberly ROBERT S. GREEN, Mexico T. BALLARD WATTERS, Marshfield Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1962 F C. BARNHILL, Marshall *RALPH P. JOHNSON, Osceola FRANK P. BRIGGS Macon ROBERT NAGEL JONES, St. Louis HENRY A. BUNDSCHU, Independence FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER, Columbia W. C. HEWITT, Shelbyville ROY D. WILLIAMS, Boonville Term Expires at Annual Meeting. 1963 RALPH P. BIEBER, St. Louis LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville BARTLETT BODER, St. Joseph W. -

A FRATERNAL ORGANIZATION of SOUTHERN MEN the CHARGE

THE NOVEMBER, 2019 LEGIONARY A Publication of the Sons of Confederate Veterans Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton Camp No. 273 Columbia, South Carolina www.wadehamptoncamp.org Charles Bray, Acting Editor A FRATERNAL ORGANIZATION OF SOUTHERN MEN COMMANDERS CORNER BILLY PITTMAN Compatriots, given this is the season of Thanksgiving, I’m going to take a few moments and express my thanks to each of you for The CHARGE your support of the camp this year. I also want to name some folks specifically and I know I will miss some names, so forgive me. My To you, SONS OF CONFEDERATE VETERANS, deepest appreciation to Charlie Bray for his unwavering efforts in we submit the VINDICATION of the cause keeping the camp (and me) on track. Charlie handles so many duties and attends so many events on our behalf, I wouldn’t even for which we fought; to your strength have space to list them. I also would like to thank Rusty Rentz for will be given the DEFENSE of the his guidance this year as I transitioned into the commander role Confederate soldier's good name, the and for leading the upcoming November meeting in my absence. GUARDIANSHIP of his history, the Terry Hughey has done an outstanding job lining up speakers for EMULATION of his virtues, the the camp this year and he has lined up speakers for nearly all of PERPETUATION of those principles he 2021 as well. I can’t understate how important that role is and loved and which made him glorious and with Terry moving out of this role in 2021, we will need someone else to take on this duty. -

The Border Star

The Border Star Official Publication of the Civil War Round Table of Western Missouri “Studying the Border War and Beyond” April 2011 The bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861 was the The Civil War Round Table Cwas was e opening engagement of the American Civil War. The 150th Anofnive Westernrsary onMissouri April 12, Anniversary of the American Civil War is upon us! ………………………………………………………………………………................. 2011 Officers President --------------- Mike Calvert 1st V.P. -------------------- Pat Gradwohl 2nd V.P. ------------------- Art Kelley President’s Letter Secretary ---------------- Karen Wells Treasurer ---------------- Beverly Shaw Many years ago when I was just a lowly freshman at the University of Missouri, Historian ------------------ Open Rolla there was a road sign just as you made the turn onto Pine Street (the main Board Members street) that read “Rolla Missouri, the Watch Me City of the Show Me State” Delbert Coin Karen Coin Little did I know that that same sign could have describe Rolla in 1861. At the Terry Chronister Barbara Hughes terminus of the St Louis-San Francisco Railroad, Rolla was a strategic depot for Don Moorehead Kathy Moorehead all the campaigns into southwest Missouri to follow. Seized by Franz Siegel for Steve Olson Carol Olson Liz Murphy Terry McConnell the Union on June 14, 1861 it remained in Union hands throughout the war. So important as a supply depot that two forts were built to protect it (Fort Wyman The Border Star Editor and Fort Dettec). 20,000 troops were stationed there under orders from President Dennis Myers Lincoln to hold it at all costs. Phil Sheridan was stationed there as a Captain in 12800 E. -

Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign George David Schieffler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2017 Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign George David Schieffler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Schieffler, George David, "Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 2426. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2426 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by George David Schieffler The University of the South Bachelor of Arts in History, 2003 University of Arkansas Master of Arts in History, 2005 August 2017 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________________ Dr. Daniel E. Sutherland Dissertation Director ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Dr. Elliott West Dr. Patrick G. Williams Committee Member Committee Member Abstract “Civil War in the Delta” describes how the American Civil War came to Helena, Arkansas, and its Phillips County environs, and how its people—black and white, male and female, rich and poor, free and enslaved, soldier and civilian—lived that conflict from the spring of 1861 to the summer of 1863, when Union soldiers repelled a Confederate assault on the town. -

Historical Review

HISTORICAL REVIEW APRIL 1963 Fred Geary's "The Steamboat Idlewild' Published Quarterly By The State Historical Society of Missouri COLUMBIA, MISSOURI THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI The State Historical Society of Missouri, heretofore organized under the laws of this State, shall be the trustee of this State—Laws of Missouri, 1899, R. S. of Mo., 1949, Chapter 183. OFFICERS 1962-65 ROY D. WILLIAMS, Boonville, President L. E. MEADOR, Springfield, First Vice President LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville, Second Vice President WILLIAM L. BRADSHAW, Columbia, Third Vice President RUSSELL V. DYE, Liberty, Fourth Vice President WILLIAM C TUCKER, Warrensburg, Fifth Vice President JOHN A. WINKLER, Hannibal, Sixth Vice President R. B. PRICE, Columbia, Treasurer FLOYD C SHOEMAKER, Columbia, Sacretary Emeritus and Consultant RICHARD S. BROWNLEE, Columbia, Director, Secretary, and Librarian TRUSTEES Permanent Trustees, Former Presidents of the Society E. L. DALE, Carthage E. E. SWAIN, Kirksville RUSH H. LIMBAUGH, Cape Girardeau L. M. WHITE, Mexico GEORGE A. ROZIER, Jefferson City Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1963 RALPH P. BIEBER, St. Louis LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville BARTLETT BODER, St. Joseph W. WALLACE SMITH, Independence L. E. MEADOR, Springfield JACK STAPLETON, Stanberry JOSEPH H. MOORE, Charleston HENRY C THOMPSON, Bonne Terre Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1964 WILLIAM R. DENSLOW, Trenton FRANK LUTHER MOTT, Columbia ALFRED O. FUERBRINGER, St. Louis GEORGE H. SCRUTON, Sedalia GEORGE FULLER GREEN, Kansas City JAMES TODD, Moberly ROBERT S. GREEN, Mexico T. BALLARD WATTERS, Marshfield Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1965 FRANK C BARNHILL, Marshall W. C HEWITT, Shelbyville FRANK P. BRIGGS, Macon ROBERT NAGEL JONES, St. -

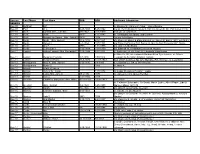

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P. m. Eleanor R. Clark 5-21-1866; stone illegible Bee-09 Purl J. C. 8-25-1898 5-25-1902 s/o Dr. Henry Bosworth & Laura Purl; b/o Aileen B. (Dr. Purl buried in CA) Bee-10 Buck Cynthia (Mrs. John #2) 2-6-1842 11-6-1930 2nd wife of John Buck Bee-10 Buck John 1807 3-25-1887 m.1st-Magdalena Spring; 2nd-Cynthia Bee-10 Buck Magdalena Spring (Mrs. John #1) 1805 1874 1st w/o John Buck Bee-10 Burris Ida B. (Mrs. James) 11-6-1858 2/12/1927 d/o Moses D. Burch & Efamia Beach; m. James R. Burris 1881; m/o Ora F. Bee-10 Burris James I. 5-7-1854 11/8/1921 s/o Robert & Pauline Rich Burris; m. Ida; f/o Son-Professor O.F. Burris Bee-10 Burris Ora F. 1886 2-11-1975 s/o James & Ida Burris Bee-10 Burris Zelma Ethel 7-15-1894 1-18-1959 d/o Elkanah W. & Mahala Ellen Smith Howard Bee-11 Lamkin Althea Leonard (Mrs. Benjamin F.) 7-15-1844 3/17/1931 b. Anderson, IN; d/o Samuel & Amanda Eads Brown b. Ohio Co, IN ; s/o Judson & Barbara Ellen Dyer Lamkin; m. Althea Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Franklin 1-7-1836 1/30/1914 Leonard; f/o Benjamin Franklin Lamkin Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Frank 11-9-1875 12-17-1943 Son of B.F. & Althea; Sp. Am. War Mo., Pvt. -

Butterfield Ja18

P O S T HASTE STORY AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY SUSAN DRAGOO Now largely forgotten, the BUTTERFIELD OVERLAND MAIL ROUTE in SOUTHEASTERN Oklahoma is a historic tie to the nation’s westward expansion. For the intrepid traveler, following its trace through the state is a WILD WEST treasure hunt. The Brazil Creek Bridge in LeFlore County is a pony truss span over a scenic spot near what was a nineteenth- century mail station. 80 July/August 2018 OklahomaToday.com 81 HE LAND STILL bears the faded scars of the old route: a swale through a pasture, a cut-down creek bank, a path worn bare Tthrough the forest. In some forgotten places, walled springs still flow near the rubble of rock buildings or graveyards of broken stones. Tey testify to the At the time, long sea journeys were the easiest mode of TRAVEL long-ago passage of the Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoaches through from the EAST COAST to the newly populous west, and the nation what would become Oklahoma. It’s been 160 years since the first needed a more efficient way to DELIVER THE MAIL. two bags of mail on the route crossed the Poteau River into Indian Territory. Today, an excursion along Oklahoma’s 192 miles of the Butterfield trail is both time warp and treasure hunt. My husband Bill and I set out to retrace the Indian Territory section of the 1858- 1861 Butterfield route, traveling the back roads of southeastern Oklahoma to discover what remains. Three-cent stamp from 1861, uspcs.org HE ROAD BEGAN in Tipton, Mis- Tsouri, at a terminus of the Pacific Railroad. -

By Bachelor of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklah

FEDERAL REFUGEES FROM INDIAN TERRITORY, 1861-1867 By JERRY LEON GILL /( Bachelor of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1967 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements fo~ the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1973 :;-1' ., '' J~~ /'77~' G415 f. •. &if'• .~:,; . ;.. , : - i \ . ..J ') .: • .·•.,. -~ 1•, j ( . i • • I OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY OCT 8 1973 FEDERAL REFUGEES FROM IND IAN TERRITORY, 1861-1867 Thesis Approvedr cPean "of the Graduate College ii PREFACE This study is concerned with the influence of the Civil War on the Indian tribes residing in Indian Territory who chose to remain loyal to the United States government during the conflict. Emphasis is placed on the Cherokee, Cree~, Chickasaw, and Seminole Indians, but all tribes and portions of Indian Territory tribes loyal to the United States during the Civil War are included in the study. Confederate military control of Indian Territory early in the Civil War forced the Indians loyal to the United States to flee north from Indian Territory. Before the war had ended,·approximately 10,500 Feder al refugee Indians had scattered across Arkansas, Missouri, Kansas, Colorado, and :Mexico. The reasons why these Indians remained loyal to the United States, their exodus from Indian Territory, their exile, and their return to Indian Territory are documented and evaluated in this study. The suffering and death expe:i;ienced by these refugees are unique in Civil War history, and far surpassed the de.privation and sacrifices made by other civilian populations. Hundreds of non-combatants,. -

Ally, the Okla- Homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: a History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989)

Oklahoma History 750 The following information was excerpted from the work of Arrell Morgan Gibson, specifically, The Okla- homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989). Oklahoma: A History of the Sooner State (University of Oklahoma Press 1964) by Edwin C. McReynolds was also used, along with Muriel Wright’s A Guide to the Indian Tribes of Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press 1951), and Don G. Wyckoff’s Oklahoma Archeology: A 1981 Perspective (Uni- versity of Oklahoma, Archeological Survey 1981). • Additional information was provided by Jenk Jones Jr., Tulsa • David Hampton, Tulsa • Office of Archives and Records, Oklahoma Department of Librar- ies • Oklahoma Historical Society. Guide to Oklahoma Museums by David C. Hunt (University of Oklahoma Press, 1981) was used as a reference. 751 A Brief History of Oklahoma The Prehistoric Age Substantial evidence exists to demonstrate the first people were in Oklahoma approximately 11,000 years ago and more than 550 generations of Native Americans have lived here. More than 10,000 prehistoric sites are recorded for the state, and they are estimated to represent about 10 percent of the actual number, according to archaeologist Don G. Wyckoff. Some of these sites pertain to the lives of Oklahoma’s original settlers—the Wichita and Caddo, and perhaps such relative latecomers as the Kiowa Apache, Osage, Kiowa, and Comanche. All of these sites comprise an invaluable resource for learning about Oklahoma’s remarkable and diverse The Clovis people lived Native American heritage. in Oklahoma at the Given the distribution and ages of studies sites, Okla- homa was widely inhabited during prehistory. -

Taining to Kansas in the Civil War

5' 4 THE EMPORIA STATE TflE GRADUATE PUBLICATION OF THE KANSAS STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE, EMPORIA . Selected, Annotated Bibliography of Sources gin the Kansas State Historical Society Per- taining to Kansas in the Civil War QuankSs mid on Lawrence, August 21, 1863 (Kansas State Historical Society) J 4' .I.-' -.- a. By Eugene Donald Decker KANSAS STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE EMPORIA, KANSAS A Selected, Annotated Bibliography of Sources ili the Kansas State Historical Society Pertaining to Kansas in the Civil War By Eugene Donald Decker <- VOLUME 9 JUNE 1961 NUMBER 4 THE EMPORIA STATE RESEARCH STUDIES is published in September, Dwember, March and June of each year by the Graduate Division of the Kansas State Teachers College, 1200 Commercial St., Emporia, Kansas. En- tered as second-class matter September 16, 1952, at the post office at Em- poria, Kansas, under the act of August 24, 1912. Postage paid at Emporia, Kansas. KANSAS STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE EMPORIA . KANSAS JOHN E. KING President of the College THE GRADUATE DIVISION LAURENCEC. BOYLAN,Dean EDITORIAL BOARD TEDI?. ANDREWS,Professor of Biology and Head of Department WILLIAMH. SEILER,Professor of Social Scknce and Chairman of Division CHARLESE. WALTON,Professor of English GREEND. WYRICK,Associate Professor of English Editor of this issue: WILLIAMH. SEILER This publication is a continuation of Studies in Educa.tion published by the Graduate Division from 1930 to 1945. Papers published in this periodical are writ'ten by faculty members of the Kansas State Teachers College of Ernporia and by either undergraduate or graduabe students whose studies are conducted in residence under the super- vision of a faculty m,ember of the college. -

From Scouts to Soldiers: the Evolution of Indian Roles in the U.S

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Summer 2013 From Scouts to Soldiers: The Evolution of Indian Roles in the U.S. Military, 1860-1945 James C. Walker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Walker, James C., "From Scouts to Soldiers: The Evolution of Indian Roles in the U.S. Military, 1860-1945" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 860. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/860 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM SCOUTS TO SOLDIERS: THE EVOLUTION OF INDIAN ROLES IN THE U.S. MILITARY, 1860-1945 by JAMES C. WALKER ABSTRACT The eighty-six years from 1860-1945 was a momentous one in American Indian history. During this period, the United States fully settled the western portion of the continent. As time went on, the United States ceased its wars against Indian tribes and began to deal with them as potential parts of American society. Within the military, this can be seen in the gradual change in Indian roles from mostly ad hoc forces of scouts and home guards to regular soldiers whose recruitment was as much a part of the United States’ war plans as that of any other group. -

The Border South and the Secession Crisis, 1859-1861 Michael Dudley Robinson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Fulcrum of the Union: The Border South and the Secession Crisis, 1859-1861 Michael Dudley Robinson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Robinson, Michael Dudley, "Fulcrum of the Union: The Border South and the Secession Crisis, 1859-1861" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 894. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/894 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. FULCRUM OF THE UNION: THE BORDER SOUTH AND THE SECESSION CRISIS, 1859- 1861 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Michael Dudley Robinson B.S. North Carolina State University, 2001 M.A. University of North Carolina – Wilmington, 2007 May 2013 For Katherine ii Acknowledgements Throughout the long process of turning a few preliminary thoughts about the secession crisis and the Border South into a finished product, many people have provided assistance, encouragement, and inspiration. The staffs at several libraries and archives helped me to locate items and offered suggestions about collections that otherwise would have gone unnoticed. I would especially like to thank Lucas R.