An Intensive Survey of Historical Resources in the Proposed Long Branch Reservoir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Border Star

The Border Star Official Publication of the Civil War Round Table of Western Missouri “Studying the Border War and Beyond” April 2011 The bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861 was the The Civil War Round Table Cwas was e opening engagement of the American Civil War. The 150th Anofnive Westernrsary onMissouri April 12, Anniversary of the American Civil War is upon us! ………………………………………………………………………………................. 2011 Officers President --------------- Mike Calvert 1st V.P. -------------------- Pat Gradwohl 2nd V.P. ------------------- Art Kelley President’s Letter Secretary ---------------- Karen Wells Treasurer ---------------- Beverly Shaw Many years ago when I was just a lowly freshman at the University of Missouri, Historian ------------------ Open Rolla there was a road sign just as you made the turn onto Pine Street (the main Board Members street) that read “Rolla Missouri, the Watch Me City of the Show Me State” Delbert Coin Karen Coin Little did I know that that same sign could have describe Rolla in 1861. At the Terry Chronister Barbara Hughes terminus of the St Louis-San Francisco Railroad, Rolla was a strategic depot for Don Moorehead Kathy Moorehead all the campaigns into southwest Missouri to follow. Seized by Franz Siegel for Steve Olson Carol Olson Liz Murphy Terry McConnell the Union on June 14, 1861 it remained in Union hands throughout the war. So important as a supply depot that two forts were built to protect it (Fort Wyman The Border Star Editor and Fort Dettec). 20,000 troops were stationed there under orders from President Dennis Myers Lincoln to hold it at all costs. Phil Sheridan was stationed there as a Captain in 12800 E. -

Historical Review

HISTORICAL REVIEW APRIL 1963 Fred Geary's "The Steamboat Idlewild' Published Quarterly By The State Historical Society of Missouri COLUMBIA, MISSOURI THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI The State Historical Society of Missouri, heretofore organized under the laws of this State, shall be the trustee of this State—Laws of Missouri, 1899, R. S. of Mo., 1949, Chapter 183. OFFICERS 1962-65 ROY D. WILLIAMS, Boonville, President L. E. MEADOR, Springfield, First Vice President LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville, Second Vice President WILLIAM L. BRADSHAW, Columbia, Third Vice President RUSSELL V. DYE, Liberty, Fourth Vice President WILLIAM C TUCKER, Warrensburg, Fifth Vice President JOHN A. WINKLER, Hannibal, Sixth Vice President R. B. PRICE, Columbia, Treasurer FLOYD C SHOEMAKER, Columbia, Sacretary Emeritus and Consultant RICHARD S. BROWNLEE, Columbia, Director, Secretary, and Librarian TRUSTEES Permanent Trustees, Former Presidents of the Society E. L. DALE, Carthage E. E. SWAIN, Kirksville RUSH H. LIMBAUGH, Cape Girardeau L. M. WHITE, Mexico GEORGE A. ROZIER, Jefferson City Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1963 RALPH P. BIEBER, St. Louis LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville BARTLETT BODER, St. Joseph W. WALLACE SMITH, Independence L. E. MEADOR, Springfield JACK STAPLETON, Stanberry JOSEPH H. MOORE, Charleston HENRY C THOMPSON, Bonne Terre Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1964 WILLIAM R. DENSLOW, Trenton FRANK LUTHER MOTT, Columbia ALFRED O. FUERBRINGER, St. Louis GEORGE H. SCRUTON, Sedalia GEORGE FULLER GREEN, Kansas City JAMES TODD, Moberly ROBERT S. GREEN, Mexico T. BALLARD WATTERS, Marshfield Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1965 FRANK C BARNHILL, Marshall W. C HEWITT, Shelbyville FRANK P. BRIGGS, Macon ROBERT NAGEL JONES, St. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the EASTERN DISTRICT of LOUISIANA ______) MALIK RAHIM ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) Civil Action No.: 2:11-Cv-02850 V

Case 2:11-cv-02850-NJB-ALC Document 5 Filed 01/17/12 Page 1 of 6 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA ____________________________________ ) MALIK RAHIM ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) Civil Action No.: 2:11-cv-02850 v. ) ) Section “G” FEDERAL BUREAU OF ) INVESTIGATION; and UNITED ) Magistrate: (5) STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE ) ) Defendants. ) ____________________________________) ANSWER Defendant, the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”), and Putative Defendant, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”), through their undersigned counsel, hereby answer Plaintiff’s Complaint for Injunctive and Declaratory Relief (“Complaint”): FIRST DEFENSE Plaintiff has failed to state a claim upon which relief can be granted. SECOND DEFENSE The Complaint seeks to impose upon the FBI obligations that exceed those imposed by the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”). THIRD DEFENSE The Complaint seeks to compel the production of records protected from disclosure by applicable exemptions. FOURTH DEFENSE The FBI is not a proper defendant in this action. Pursuant to 5 U.S.C. § 552(f)(1), the proper party defendant is the DOJ. Case 2:11-cv-02850-NJB-ALC Document 5 Filed 01/17/12 Page 2 of 6 FIFTH DEFENSE Defendants respond to each numbered paragraph of Plaintiff’s Complaint as follows: 1. Paragraph 1 consists of Plaintiff’s characterization of his Complaint, to which no response is required. 2. Defendants lack knowledge or information sufficient to form a belief as to the truth of the allegations in Paragraph 2. 3. Defendants lack knowledge or information sufficient to form a belief as to the truth of the allegations in Paragraph 3. -

2021 MJS Bios-Photos 6.28

MASTER OF JUDICIAL STUDIES PROGRAM 2021‐2023 PARTICIPANT BIOGRAPHIES Micaela Alvarez Judge, U.S. District Court, Southern District of Texas McAllen, Texas Micaela Alvarez was born in Donna, Texas on June 8, 1958 to Evencio and Macaria Alvarez. Judge Alvarez graduated from Donna High School in 1976, after only three years in high school. She attended the University of Texas at Austin where, in 1980, she obtained a bachelor’s degree in Social Work. Judge Alvarez then attended the University of Texas School of Law and graduated in 1989. After graduation from law school, Judge Alvarez returned to the Rio Grande Valley where she began practicing law with the firm of Atlas & Hall, L.L.P. She left that firm and joined the Law Offices of Ronald G. Hole in 1993. In 1995, Judge Alvarez was appointed by then Governor Bush to serve as a District Judge for the 139th Judicial District Court in Hidalgo County. Judge Alvarez was the first woman to sit as a District Judge in Hidalgo County. In 1997, she returned to private practice and was a founding partner in the Law Offices of Hole & Alvarez, L.L.P. In mid‐2004, Judge Alvarez was nominated by President Bush to serve as a United States District Judge for the Southern District of Texas. She was confirmed by the Senate in November 2004. Judge Alvarez first served in the Laredo Division of the Southern District of Texas where she was again the first female District Judge and now serves as a United States District Judge in McAllen, Texas. -

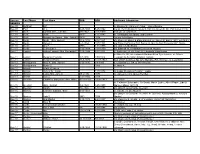

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P. m. Eleanor R. Clark 5-21-1866; stone illegible Bee-09 Purl J. C. 8-25-1898 5-25-1902 s/o Dr. Henry Bosworth & Laura Purl; b/o Aileen B. (Dr. Purl buried in CA) Bee-10 Buck Cynthia (Mrs. John #2) 2-6-1842 11-6-1930 2nd wife of John Buck Bee-10 Buck John 1807 3-25-1887 m.1st-Magdalena Spring; 2nd-Cynthia Bee-10 Buck Magdalena Spring (Mrs. John #1) 1805 1874 1st w/o John Buck Bee-10 Burris Ida B. (Mrs. James) 11-6-1858 2/12/1927 d/o Moses D. Burch & Efamia Beach; m. James R. Burris 1881; m/o Ora F. Bee-10 Burris James I. 5-7-1854 11/8/1921 s/o Robert & Pauline Rich Burris; m. Ida; f/o Son-Professor O.F. Burris Bee-10 Burris Ora F. 1886 2-11-1975 s/o James & Ida Burris Bee-10 Burris Zelma Ethel 7-15-1894 1-18-1959 d/o Elkanah W. & Mahala Ellen Smith Howard Bee-11 Lamkin Althea Leonard (Mrs. Benjamin F.) 7-15-1844 3/17/1931 b. Anderson, IN; d/o Samuel & Amanda Eads Brown b. Ohio Co, IN ; s/o Judson & Barbara Ellen Dyer Lamkin; m. Althea Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Franklin 1-7-1836 1/30/1914 Leonard; f/o Benjamin Franklin Lamkin Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Frank 11-9-1875 12-17-1943 Son of B.F. & Althea; Sp. Am. War Mo., Pvt. -

United States District Court Eastern District of Louisiana

Case 2:12-md-02328-SSV Document 718 Filed 04/29/16 Page 1 of 12 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA MDL NO. 2328 IN RE: POOL PRODUCTS DISTRIBUTION MARKET ANTITRUST SECTION: R(2) LITIGATION JUDGE VANCE MAG. JUDGE WILKSON THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO ALL DIRECT-PURCHASER PLAINTIFF CASES ORDER AND REASONS Defendants Pool Corporation, SCP Distributors LLC, and Superior Pool Products (collectively, “Pool”), move for summary judgment on Direct Purchaser Plaintiffs’ (DPPs’) vertical conspiracy claims, as well as Indirect Purchaser Plaintiffs (IPPs’) analogous state-law claims.1 DPPs have alleged that Pool maintained an unlawful vertical agreement with each Manufacturer Defendant—Hayward Industries, Inc., Pentair Water Pool and 1 R. Doc. 504 (Motion for Summary Judgment on Claim of Vertical Conspiracy Between Pool and Hayward); R. Doc. 506 (Motion for Summary Judgment on Claim of Vertical Conspiracy Between Pool and Zodiac); R. Doc. 517 (Motion for Summary Judgment on Claim of Vertical Conspiracy Between Pool and Pentair). Case 2:12-md-02328-SSV Document 718 Filed 04/29/16 Page 2 of 12 Spa, Inc., and Zodiac Pool Systems, Inc. For the following reasons, the Court grants the motion. I. BACKGROUND This is an antitrust case that direct-purchaser plaintiffs (DPPs) and indirect-purchaser plaintiffs (IPPs) filed against Pool and the Manufacturer Defendants. Pool is the country’s largest distributor of products used for the construction and maintenance of swimming pools (Pool Products).2 The Manufacturer Defendants are the three largest manufacturers of Pool Products in the United States: Hayward, Zodiac, and Pentair.3 As defined in DPPs’ Second Consolidated Amended Class Action Complaint and IPPs’ Third Amended Class Action Complaint, Pool Products are the equipment, products, parts, and materials used for the construction, renovation, maintenance, repair, and service of residential and commercial swimming pools. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT of LOUISIANA JONATHAN P. ROBICHEAUX CIVIL ACTION V. NO. 13-5090 JAMES D. CALDWELL

Case 2:13-cv-05090-MLCF-ALC Document 33 Filed 11/27/13 Page 1 of 7 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA JONATHAN P. ROBICHEAUX CIVIL ACTION v. NO. 13-5090 JAMES D. CALDWELL, SECTION "F" LOUISIANA ATTORNEY GENERAL ORDER & REASONS Before the Court are defendant's motions to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction and to dismiss or transfer for improper venue. For the reasons that follow, the motion to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction is GRANTED, and the motion to dismiss or transfer for improper venue is DENIED as moot. Background This civil rights lawsuit challenges the constitutionality of Louisiana's ban on same-sex marriage and its unwillingness to recognize same-sex marriages entered into in other states. Jonathan Robicheaux married his same-sex partner in Iowa, but he lives in Orleans Parish, Louisiana. He alleges that Louisiana's defense of marriage amendment to the state constitution (La. Const. art. 12, § 15) and Article 3520 of the Louisiana Civil Code (which decrees that same-sex marriage violates Louisiana's strong public policy and precludes recognition of any such marriage contract from 1 Case 2:13-cv-05090-MLCF-ALC Document 33 Filed 11/27/13 Page 2 of 7 another state) violate his federal constitutional rights.1 Robicheaux first brought this suit alone, but has since amended his complaint to include his partner, Derek Penton, and another same-sex couple who were also married in Iowa, but now live in Louisiana, Nadine and Courtney Blanchard. The plaintiffs sued the Louisiana Attorney General James "Buddy" Caldwell, the only defendant in this lawsuit. -

1 United States District Court Middle District of Louisiana

Case 3:19-cv-00479-JWD-SDJ Document 58 10/19/20 Page 1 of 27 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA LOUISIANA STATE CONFERENCE OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, ET AL. CIVIL ACTION VERSUS NO. 19-479-JWD-SDJ STATE OF LOUISIANA, ET AL. RULING AND ORDER This matter comes before the Court on the Joint Motion for Certification of Order for Interlocutory Appeal (the “Motion for Interlocutory Appeal”) (Doc. 51) pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b) filed by Defendants, the State of Louisiana and the Secretary of State of Louisiana (collectively, “Defendants”). Plaintiffs, the Louisiana State Conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (“NAACP”), Anthony Allen, and Stephanie Allen (collectively, “Plaintiffs”), oppose the motion. (Doc. 54.) Defendants filed a reply. (Doc. 56.) Oral argument is not necessary. The Court has carefully considered the law, the facts in the record, and the arguments and submissions of the parties and is prepared to rule. For the following reasons, Defendants’ motion is granted in part and denied in part. I. Relevant Factual and Procedural Background A. Factual Background Plaintiffs brought suit under the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 52 U.S.C. § 10301 et seq. (Doc. 1.) In the Complaint, Plaintiffs discuss, inter alia, Chisom v. Roemer, 501 U.S. 380, 111 S. Ct. 2354, 115 L. Ed. 2d 348 (1991), where minority plaintiffs challenged the original electoral process for the Louisiana Supreme Court, which consisted of six judicial districts, five single- 1 Case 3:19-cv-00479-JWD-SDJ Document 58 10/19/20 Page 2 of 27 member districts and one multi-member district which encompassed Orleans Parish and which elected two justices. -

Eastern District of Louisiana Criminal No.20.066 Factual

Case 2:20-cr-00066-JCZ-DMD Document 19 Filed 03/30/21 Page 1 of 5 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA {. CRIMINAL NO.20.066 v. *< SECTION: A emrrffi #lsfflcrTo?tffiIsrnrua BRADLEY EDWARD CORLEY * FILED ]'tAR 3 0 2021 ,< {< {. FACTUAL BASIS CAROL L, MICHE CLERK The defendant, BRAI)LEY EDWARD CORLEY (hereinafter, the "defendant" or "CORLEY"), has agreed to plead guilty to Count Two of the Indictment currently pending against him, charging CORLEY with possession of child sexual abuse material, in violation of Title 18, United States Code, Section 2252($@)(8). Should this maffer proceed to trial, both the Government and the defendant, BRADLEY EDWARD CORLEY, do hereby stipulate and agree that the following facts set forth a sufficient factual basis for the crimes to which the defendant is pleading guilty. The Govemment and the defendant further stipulate that the Government would have proven, through the introduction of competent testimony and admissible, tangible exhibits, the following facts, beyond a reasonable doubt, to support the allegations in the Indictment now pending against the defendant: The Govemment would show that, at all times mentioned in the Indictment, the defendant, CORLEY, was a resident of the Eastem District of Louisiana and lived in Marrero, Louisiana. The Government would further establish that on April27 ,2006, CORLEY was convicted in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana of Possession of Materials Involving the Sexual Exploitation of Minors, in violation of Title I 8, United States Code, Section 2252(a)(\(B), under case number 05-197. -

Council and Participants

The American Law Institute DAVID F. LEVI, President ROBERTA COOPER RAMO, Chair of the Council DOUGLAS LAYCOCK, 1st Vice President LEE H. ROSENTHAL, 2nd Vice President WALLACE B. JEFFERSON, Treasurer PAUL L. FRIEDMAN, Secretary RICHARD L. REVESZ, Director STEPHANIE A. MIDDLETON, Deputy Director COUNCIL KIM J. ASKEW, K&L Gates, Dallas, TX JOSE I. ASTIGARRAGA, Reed Smith, Miami, FL DONALD B. AYER, Jones Day, Washington, DC SCOTT BALES, Arizona Supreme Court, Phoenix, AZ JOHN H. BEISNER, Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, Washington, DC JOHN B. BELLINGER III, Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer LLP, Washington, DC AMELIA H. BOSS, Drexel University Thomas R. Kline School of Law, Philadelphia, PA ELIZABETH J. CABRASER, Lieff Cabraser Heimann & Bernstein, San Francisco, CA EVAN R. CHESLER, Cravath, Swaine & Moore, New York, NY MARIANO-FLORENTINO CUELLAR, California Supreme Court, San Francisco, CA IVAN K. FONG, 3M Company, St. Paul, MN KENNETH C. FRAZIER, Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ PAUL L. FRIEDMAN, U.S. District Court, District of Columbia, Washington, DC STEVEN S. GENSLER, University of Oklahoma College of Law, Norman, OK ABBE R. GLUCK, Yale Law School, New Haven, CT YVONNE GONZALEZ ROGERS, U.S. District Court, Northern District of California, Oakland, CA ANTON G. HAJJAR, Chevy Chase, MD TERESA WILTON HARMON, Sidley Austin, Chicago, IL NATHAN L. HECHT, Texas Supreme Court, Austin, TX WILLIAM C. HUBBARD, Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough, Columbia, SC SAMUEL ISSACHAROFF, New York University School of Law, New York, NY KETANJI BROWN JACKSON, U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, Washington, DC WALLACE B. JEFFERSON, Alexander Dubose & Jefferson LLP, Austin, TX GREGORY P. -

Missouri Historical Revi Ew

MISSOURI HISTORICAL REVI EW. CONTENTS George Engelmann, Man of Science William G. Bek The National Old Trails Road at Lexington B. M. Little The Blairs and Fremont William E. Smith An Early Missouri Political Fend Roy V, Magers The Great Seal of the State of Missouri Perry S. Rader Historical Notes and Comments Missouri History Not Found in Textbooks STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY of MISSOURI VOL. XXIII JANUARY, 1929 NO. 2 OFFICERS OF THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI, 1925-1928 GEORGE A. MAHAN, Hannibal, President. LOUIS T. GOLDING, St. Joseph, First Vice-President. WALTER B. STEVENS, St. Louis, Second Vice-President. WALTER S. DICKEY, Kansas City, Third Vice-President. CORNELIUS ROACH, Kansas City, Fourth Vice-President. E. N. HOPKINS, Lexington, Fifth Vice-President. ALLEN McREYNOLDS, Carthage, Sixth Vice-President. R. B. PRICE, Columbia, Treasurer. FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER, Secretary and Librarian. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1928 ROLLIN J. BRITTON, Kansas ISIDOR LOEB, St. Louis. City. C. H. McCLURE Kirksville. T. H. B. DUNNEGAN, Bolivar. JOHN ROTHENSTEINER, BEN L. EMMONS, St. Charles. St. Louis. STEPHEN B. HUNTER, CHAS. H. WHITAKER, Cape Girardeau. Clinton. Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1929 PHIL A. BENNETT, Springfield. J. F. HULL, Maryville. JOSEPH A. CORBY, St. Joseph. ELMER O. JONES, LaPlata. W. E. CROWE, DeSoto. WM. SOUTHERN, JR. FORREST C. DONNELL, Independence. St. Louis. CHARLES L. WOODS, Rolla. BOYD DUDLEY, Gallatin. Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1930 C. P. DORSEY, Cameron. H. S. STURGIS, Neosho. EUGENE FAIR, Kirksville. JONAS VILES, Columbia. THEODORE GARY, Kansas City. R. M. WHITE, Mexico. GEORGE A. MAHAN, Hannibal. -

Kirksville Daily Express - Tuesday, August 6, 1912

Kirksville Daily Express - Tuesday, August 6, 1912 1862 – AUGUST 6 – 1912 We present today our special edition commemorating the battle of Kirksville which was fought just fifty years ago today, and a series of reminiscences of people who either participated in or witnessed the battle. The task of collating these reminiscences has been assumed by Prof. Violette of the history department of our State Normal School. In his interviews with those who were participants or mere witnesses of the events of the day, he has sought for statements of what they personally saw or did, and not what somebody else saw or did. The reminiscences, therefore, have some peculiar historical value because of this fact. The original intention was to include reminiscences of only those who were here at the time of the battle, either as soldiers or residents, and who are still living here; but it was soon discovered that if the stories of any of the soldiers who participated in the battle were to be included it would be necessary to make an exception to the rule. As far as it is known there is not now a single person living in Kirksville who participated in the battle itself. For many years, Mr. S. M. Johnson, one of McNeil’s men lived here, but he died less than a year ago. We have been fortunate however, in securing an account of the battle from two old soldiers, Captain George H. Rowell, of Battle Creek, Mich., who was under McNeil, and Mr. G. R. Cummings, of Adair County, who was under Porter.