Yeats, Reincarnation, and Resolving the Antinomies of the Body-Soul Dilemma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Version Available at Special Issue on WB Yeats Volume 1, Number 3, 2015

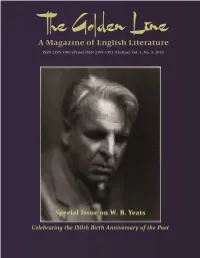

The Golden Line A Magazine of English Literature Online version available at www.goldenline.bcdedu.net Special Issue on W. B. Yeats Volume 1, Number 3, 2015 Guest-edited by Dr. Zinia Mitra Nakshalbari College, Darjeeling Published by The Department of English Bhatter College, Dantan P.O. Dantan, Dist. Paschim Medinipur West Bengal, India. PIN 721426 Phone: 03229-253238, Fax: 03229-253905 Website: www.bhattercollege.ac.in Email: [email protected] The Golden Line: A Magazine on English Literature Online version available at www.goldenline.bcdedu.net ISSN 2395-1583 (Print) ISSN 2395-1591 (Online) Inaugural Issue Volume 1, Number 1, 2015 Published by The Department of English Bhatter College, Dantan P.O. Dantan, Dist. Paschim Medinipur West Bengal, India. PIN 721426 Phone: 03229-253238, Fax: 03229-253905 Website: www.bhattercollege.ac.in Email: [email protected] © Bhatter College, Dantan Patron Sri Bikram Chandra Pradhan Hon’ble President of the Governing Body, Bhatter College Chief Advisor Pabitra Kumar Mishra Principal, Bhatter College Advisory Board Amitabh Vikram Dwivedi Assistant Professor, Shri Mata Vaishno Devi University, Jammu & Kashmir, India. Indranil Acharya Associate Professor, Vidyasagar University, West Bengal, India. Krishna KBS Assistant Professor in English, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, Dharamshala. Subhajit Sen Gupta Associate Professor, Department of English, Burdwan University. Editor Tarun Tapas Mukherjee Assistant Professor, Department of English, Bhatter College. Editorial Board Santideb Das Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Payel Chakraborty Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Mir Mahammad Ali Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Thakurdas Jana Guest Lecturer, Bhatter College ITI, Bhatter College External Board of Editors Asis De Assistant Professor, Mahishadal Raj College, Vidyasagar University. -

YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares Beside the Edmund Dulac Memorial Stone to W

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/194 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the same series YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 1, 2 Edited by Richard J. Finneran YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 3-8, 10-11, 13 Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS AND WOMEN: YEATS ANNUAL No. 9: A Special Number Edited by Deirdre Toomey THAT ACCUSING EYE: YEATS AND HIS IRISH READERS YEATS ANNUAL No. 12: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould and Edna Longley YEATS AND THE NINETIES YEATS ANNUAL No. 14: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS’S COLLABORATIONS YEATS ANNUAL No. 15: A Special Number Edited by Wayne K. Chapman and Warwick Gould POEMS AND CONTEXTS YEATS ANNUAL No. 16: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould INFLUENCE AND CONFLUENCE: YEATS ANNUAL No. 17: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares beside the Edmund Dulac memorial stone to W. B. Yeats. Roquebrune Cemetery, France, 1986. Private Collection. THE LIVING STREAM ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF A. NORMAN JEFFARES YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 A Special Issue Edited by Warwick Gould http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Gould, et al. (contributors retain copyright of their work). The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text. -

Introduction 1 a New Order

Notes Introduction 1. Alex Owen, The Place of Enchantment: British Occultism and the Culture of the Modern (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 120. 2. Corinna Treitel, A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), 3–4. Such scientists included Karl Friedrich Zöller, a well-respected professor of astrophysics at the University of Leipzig, physicists William Edward Weber and Gustav Theodor Fechner, mathematician Wilhelm Scheibner and the psychologist Wilhelm Wundt. 3. Owen, The Place of Enchantment. 4. Treitel, A Science for the Soul. 5. David Allen Harvey, Beyond Enlightenment: Occultism and Politics in Modern France (Dekalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2005). 6. For a thorough discussion of the struggle by historians to establish the enchanted nature of the modern see Michael Saler ‘Modernity and Enchantment: A Historiographic Review,’ American Historical Review, 2006 111 (3): 629–716. 7. Nicola Bown, ‘Esoteric Selves and Magical Minds,’ History Workshop Journal, 2006 61 (1): 281–7, 284, 286. Similar criticism comes from Michael Saler. Michael Saler, review of The Place of Enchantment: British Occultism and the Culture of the Modern, by Alex Owen, American Historical Review 2005 110 (3): 871–2, 872. 1 A New Order 1. R.A. Gilbert, Revelations of the Golden Dawn: The Rise and Fall of a Magical Order (London: Quantum, 1997), 34. 2. Gilbert, Revelations, 45. 3. Ellic Howe, The Magicians of the Golden Dawn: A Documentary History of a Magical Order 1887–1923 (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1972; York Beach, Maine: Samuel Weiser, 1978). Gilbert, Revelations. -

Predetermination and Nihilism in W. B. Yeats's Theatre

Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses 5 (1992): 143-53 Predetermination and Nihilism in W. B. Yeats's Theatre Francisco Javier Torres Ribelles University of Alicante ABSTRACT This paper puts forward the hypothesis that Yeats's theatre is affected by a determinist component that governs it. This dependence is held to be the natural consequence of his desire to créate a universal art, a wish that confines the writer to a limited number of themes, death and oíd age being the most important. The paper also argües that the deter- minism is positive in the early stage but that it clearly evolves towards a negative kind. In spite of the playwright's acknowledged interest in doctrines related to the occult, the necessity of a more critical analysis is also put forward. The paper goes on to suggest that underlying the negative determinism of Yeats's late period there is a nihilistic view of life, of life after death and even of the work of art. The paper concludes by arguing that the poet may have exaggerated his pose as a response to his admitted inability to change the modern world and as a means of overcoming his sense of impending annihilation. The attitude underlying Yeats's earliest plays is radically opposed to what we find in the final ones. In the first stage, the determinism to which the subject matter inevitably leads is given a positive character by being adapted to the author's perspective. There is an emphasis on the power of art and a celebration of the Nietzschean-romantic valúes defended by the poet. -

Introduction • the Hoodwinking • the Occult Revival O the Who's Who List of 19Th & 20Th Century Occultism

• Introduction • The Hoodwinking • The Occult Revival o The Who's Who List of 19th & 20th Century Occultism . Arthur Edward Waite . Dr. Wynn Westcott . S. L. MacGregor Mathers . Aleister Crowley . Dr. Gérard Encausse . Dr. Theodor Reuss . George Pickingill . Annie Besant . C. W. Leadbeater . Manly P. Hall . Gerald B. Gardner o Theosophy o O.T.O.: Ordo Templi Orientis • Conclusion • End Notes • Appendix: Quotations Introduction The article located at this URL, and earlier at Geocities, was first written 4 years ago. Since then I have learned a bit more about Freemasonry and have had many communications, good and bad, with its members. I've been put on an "anti-mason" [hit]list, along with others who dare to write anything unflattering against the brethren; I've had heated debates and arguments in public forums and message boards; and I've actually been threatened, both subtly and overtly. Curiously, many times the offended Mason claims to be a chaplain, a minister or a supposed "man of cloth" - a real surprise, at first, considering the occult nature of the organization. The negative experiences far outweigh the positive. The members who regularly post to forums and send out emails display the traits of having been thoroughly brainwashed by a first-class cult. Some are far more clever, however, and are undoubtedly part of a concerted effort by the Brotherhood. See, Masonic Disinformation, Propaganda, Dissembling, and Hate Techniques for a concise elaboration of their techniques. Historically, Freemasonry has been charged with corruption of public officials because of the oaths and promises they swear to keep amongst themselves, above all else. -

A Time Line of the Global History of Esotericism with Emphasis for Yoga Science on the West Since the European Renaissance

A Time Line of the Global History of Esotericism With Emphasis for Yoga Science on the West since the European Renaissance Scott Virden Anderson1 – http://www.yogascienceproject.org Email: [email protected] Draft 5/25/08 This is incomplete, a work in progress, a snapshot as of the draft date. To take it any further would consume more time that I have right now, so I’m setting it aside for the moment and posting this version as is. Note especially that the most recent part of the story is not well covered here and you’ll find only a few entries for the 20th Century (and there is much more to the story in the 19th Century as well) – interested readers can get a good feel for this more recent period of esotericist history by consulting just three books: Fields 1981,2 Hanegraaff 1998,3 and De Michelis 2004.4 Fields gives a good overview of Buddhism’s journey to the West since the 18th Century, Hanegraaff tells the story of the Western esotericisms that were “here to begin with,” and De Michelis recounts how “Modern Yoga” came to the West already “well predigested” for Westerners by Anglicized Indian Yogis themselves. My feeling is that at this point esotericism is best thought of as a global phenomenon. However, some scholars feel this approach is overly broad. Of particular importance for my Yoga Science project is the modern period beginning with the European Renaissance – since the notions of “science” first arose and came into contact with the older traditions of esotericism only in these past 800 years. -

A Cultural History of Tarot

A Cultural History of Tarot ii A CULTURAL HISTORY OF TAROT Helen Farley is Lecturer in Studies in Religion and Esotericism at the University of Queensland. She is editor of the international journal Khthónios: A Journal for the Study of Religion and has written widely on a variety of topics and subjects, including ritual, divination, esotericism and magic. CONTENTS iii A Cultural History of Tarot From Entertainment to Esotericism HELEN FARLEY Published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © Helen Farley, 2009 The right of Helen Farley to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN 978 1 84885 053 8 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress catalog card: available Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham from camera-ready copy edited and supplied by the author CONTENTS v Contents -

The Problem of Disenchantment: Scientific Naturalism and Esoteric Discourse, 1900-1939

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The problem of disenchantment: scientific naturalism and esoteric discourse, 1900-1939 Asprem, E. Publication date 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Asprem, E. (2013). The problem of disenchantment: scientific naturalism and esoteric discourse, 1900-1939. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 12 Perceiving Higher Worlds Two Perspectives I slept with faith and found a corpse in my arms on awakening; I drank and danced all night with doubt and found her a virgin in the morning. Aleister Crowley, The Book of Lies (1913), chapter 44. INTRODUCTION: A COMPARATIVE APPROACH TO HIGHER KNOWLEDGE Esoteric claims to higher knowledge are usually about much more than stating superior facts, no matter how exotic or unusual. -

W. B. Yeats: a Life and Times

W. B. Yeats: A Life and Times Readers should be alerted to the fact that there are some disparities of dates between the chronologies of Yeats's life in some of the books listed in the Guide to Further Reading. 1858 Irish Republican Brotherhood founded. 1865 13 June, William Butler Yeats born at Georgeville, Sandymount Avenue, in Dublin, son of John Butler Yeats and Susan Yeats (nee Pollexfen). 1867 Family moves to London (23 Fitzroy Road, Regent's Park), so that father can follow a career as a portrait painter. Brothers Robert and Jack and sister Elizabeth born here. The Fenian Rising and execution of the 'Manchester Martyrs'. 1872 Yeats spends an extended holiday with maternal grandparents at Sligo in West of Ireland. 1873 Founding of the Home Rule League. 1874 Family moves to 14 Edith Villas, West Kensington. 1876 Family moves to 8 Woodstock Road, Bedford Park, Chiswick. 1877--80 Yeats attends Godolphin School, Hammersmith, London. Holidays in Sligo. 1877 Charles Stewart Parnell chairman of the Home Rule League. 1879 Irish Land League founded by Parnell and Michael Davitt. 188~1 A decline in J. B. Yeats's income because of the Irish Land War sends the family back to Ireland (Balscadden Cottage, Howth, County Dublin), while he remains in London. 159 160 W. B. Yeats: A Critical Introduction 1881-3 Yeats attends Erasmus Smith High School, Harcourt St, Dublin 1882 Family moves to Island View, Howth. Yeats spends holidays with uncle George Pollexfen, Sligo. Writes first poems. Adolescent passion for his cousin Laura Armstrong. Phoenix Park Murders. Land League suppressed. -

Changing Images of Purgatory in Selected Us

FROM PAINFUL PRISON TO HOPEFUL PURIFICATION: CHANGING IMAGES OF PURGATORY IN SELECTED U.S. CATHOLIC PERIODICALS, 1909-1960 Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Timothy G. Dillon UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December, 2013 FROM PAINFUL PRISON TO HOPEFUL PURIFICATION: CHANGING IMAGES OF PURGATORY IN SELECTED U.S. CATHOLIC PERIODICALS, 1909-1960 Name: Dillon, Timothy Gerard APPROVED BY: __________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph. D. Faculty Advisor __________________________________________ Patrick Carey, Ph.D. External Faculty Reader __________________________________________ Dennis Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader __________________________________________ Anthony Smith, Ph.D. Faculty Reader __________________________________________ Sandra Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ii ABSTRACT FROM PAINFUL PRISON TO HOPEFUL PURIFICATION: CHANGING IMAGES OF PURGATORY IN SELECTED U.S. CATHOLIC PERIODICALS, 1909-1960 Name: Dillon, Timothy Gerard University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. William L. Portier Prior to 1960, U.S. Catholic periodicals regularly featured articles on the topic of purgatory, especially in November, the month for remembering the dead. Over the next three decades were very few articles on the topic. The dramatic decrease in the number of articles concerning purgatory reflected changes in theology, practice, and society. This dissertation argues that the decreased attention -

WHAT YOU SHOULD KNOW ABOUT the GOLDEN DAWN Copyright © 1983 by the Israel Regardie Foundation

WHAT YOU SHOULD KNOW ABOUT THE GOLDEN DAWN Copyright © 1983 by The Israel Regardie Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this book, in part or in whole, may be reproduced, transmitted or utilized, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except for brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. International Standard Book Number: 0-941404-15-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 83-81663 First Edition 1936 Second Edition 1971 Third Edition, revised 1983 Falcon Press, 3660 N. 3rd. St. Phoenix, Arizona 85012 (602) 246-3546 Manufactured in the United States of America CONTENTS Foreword VII Introduction XIII The Golden Dawn 7 Scandal 27 Light 56 Darkness 94 Light in Extension 120 Some Modern Critics 141 Suster's answer to Howe Mathers' Manifesto 181 LIST OF ERRATA Page 15. 4th line from the bottom, last word "with" should be "within" 39. 3rd. Delete "s" from "Obligations". 28th. First word should be plural "poseurs". 31st. "dubions" not "budious". 56. 28th. Subsititue comma for period. Delete "And" after origin and insert "then". 58. 4th line from bottom. Delete last "e" in employes. 68. 17th. Delete "one of". 72. 3rd. "Portal" not "portal". 32nd. "Commit" not "comit". 82. 25th. "animo" should be "anima". 83. 14th. "Tipharath" should be "Tiphareth". 87. 11th. "Offiice" should be "office". 88. 10th. "are" should be "were". 99. 15th. "about" should be "above". 102. 24th. "indentical" should be "identical". 107. 17th."was" should be "is". 109. -

The Key to Theosophy by H. P. Blavatsky

Theosophical University Press Online Edition THE KEY TO THEOSOPHY BY H. P. BLAVATSKY Being a Clear Exposition, in the Form of Question and Answer, of the ETHICS, SCIENCE, AND PHILOSOPHY for the Study of which The Theosophical Society has been Founded. Originally published 1889. Theosophical University Press electronic version ISBN 1- 55700-046-8 (print version also available). Due to current limitations in the ASCII character set, and for ease of searching, no diacritical marks appear in this electronic version of the text. Dedicated by "H. P. B." To all her Pupils that They may Learn and Teach in their turn. CONTENTS PREFACE SECTION 1: THEOSOPHY AND THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY (28K) ● The Meaning of the Name ● The Policy of the Theosophical Society ● The Wisdom-Religion Esoteric in all Ages ● Theosophy is not Buddhism SECTION 2: EXOTERIC AND ESOTERIC THEOSOPHY (44K) ● What the Modern Theosophical Society is not ● Theosophists and Members of the "T. S." ● The Difference between Theosophy and Occultism ● The Difference between Theosophy and Spiritualism ● Why is Theosophy accepted? SECTION 3: THE WORKING SYSTEM OF THE T. S. (22K) ● The Objects of the Society ● The Common Origin of Man ● Our other Objects ● On the Sacredness of the Pledge SECTION 4: THE RELATIONS OF THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY TO THEOSOPHY (15K) ● On Self-Improvement ● The Abstract and the Concrete SECTION 5: THE FUNDAMENTAL TEACHINGS OF THEOSOPHY (39K) ● On God and Prayer ● Is it Necessary to Pray? ● Prayer Kills Self-Reliance ● On the Source of the Human Soul ● The Buddhist