Insitutional and Social Responses to Hazards Related to Karthala Volcano, Comoros: Part I: Analysis of the May 2006 Eruptive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ing in N the E

Migrant fishers and fishing in the Western Indian Ocean: Socio-economic dynamics and implications for management Februaryr , 2011 PIs: Innocent Wanyonyi (CORDIO E.A, Kenya / Linnaeus University, Sweden) Dr Beatrice Crona (Stockholm Resilience Center, University of Stockholm, Sweden) Dr Sérgio Rosendo (FCSH, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal / UEA, UK) Country Co‐Investigators: Dr Simeon Mesaki (University of Dar es Salaam)‐ Tanzania Dr Almeida Guissamulo (University of Eduardo Mondlane)‐ Mozambique Jacob Ochiewo (Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute)‐ Kenya Chris Poonian (Community Centred Conservation)‐ Comoros Garth Cripps (Blue Ventures) funded by ReCoMaP ‐Madagascar Research Team members: Steven Ndegwa and John Muturi (Fisheries Department)‐ Kenya Tim Daw (University of East Anglia, UK)‐ Responsible for Database The material in this report is based upon work supported by MASMA, WIOMSA under Grant No. MASMA/CR/2008/02 Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendation expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the WIOMSA. Copyright in this publication and in all text, data and images contained herein, except as otherwise indicated, rests with the authors and WIOMSA. Keywords: Fishers, migration, Western Indian Ocean. Page | 1 Recommended citation: WIOMSA (2011). Migrant fishers and fishing in the Western Indian Ocean: Socio‐economic dynamics and implications for management. Final Report of Commissioned Research Project MASMA/CR/2008/02. Page | 2 Table of Contents -

Centre Souscentreserie Numéro Nom Et Prenom

Centre SousCentreSerie Numéro Nom et Prenom MORONI Chezani A1 2292 SAID SAMIR BEN YOUSSOUF MORONI Chezani A1 2293 ADJIDINE ALI ABDOU MORONI Chezani A1 2297 FAHADI RADJABOU MORONI Chezani A4 2321 AMINA ASSOUMANI MORONI Chezani A4 2333 BAHADJATI MAOULIDA MORONI Chezani A4 2334 BAIHAKIYI ALI ACHIRAFI MORONI Chezani A4 2349 EL-ANZIZE BACAR MORONI Chezani A4 2352 FAOUDIA ALI MORONI Chezani A4 2358 FATOUMA MAOULIDA MORONI Chezani A4 2415 NAIMA SOILIHI HAMADI MORONI Chezani A4 2445 ABDALLAH SAID MMADINA NABHANI MORONI Chezani A4 2449 ABOUHARIA AHAMADA MORONI Chezani A4 2450 ABOURATA ABDEREMANE MORONI Chezani A4 2451 AHAMADA BACAR MOUKLATI MORONI Chezani A4 2457 ANRAFA ISSIHAKA MORONI Chezani A4 2458 ANSOIR SAID AHAMADA MORONI Chezani A4 2459 ANTOISSI AHAMADA SOILIHI MORONI Chezani D 2509 NADJATE HACHIM MORONI Chezani D 2513 BABY BEN ALI MSA MORONI Dembeni A1 427 FAZLAT IBRAHIM MORONI Dembeni A1 464 KASSIM YOUSSOUF MORONI Dembeni A1 471 MOZDATI MMADI ADAM MORONI Dembeni A1 475 SALAMA MMADI ALI MORONI Dembeni A4 559 FOUAD BACAR SOILIHI ABDOU MORONI Dembeni A4 561 HAMIDA IBRAHIM MORONI Dembeni A4 562 HAMIDOU BACAR MORONI Dembeni D 588 ABDOURAHAMANE YOUSSOUF MORONI Dembeni D 605 SOIDROUDINE IBRAHIMA MORONI FoumboudzivouniA1 640 ABDOU YOUSSOUF MORONI FoumboudzivouniA1 642 ACHRAFI MMADI DJAE MORONI FoumboudzivouniA1 643 AHAMADA MOUIGNI MORONI FoumboudzivouniA1 654 FAIDATIE ABDALLAH MHADJOU MORONI FoumbouniA4 766 ABDOUCHAKOUR ZAINOUDINE MORONI FoumbouniA4 771 ALI KARIHILA RABOUANTI MORONI FoumbouniA4 800 KARI BEN CHAFION BENJI MORONI FoumbouniA4 840 -

Plan D'aménagement Et De Gestion Du Parc National Cœlacanthe 2017

Parcs Nationaux RNAPdes Comores UNION DES COMORES Unité – Solidarité – Développement Vice-Présidence Chargée du Ministère de l’Agriculture, de la Pêche, de l’Environnement, de l’Aménagement du Territoire et de l’Urbanisme Parcs Nationaux des Comores Plan d’Aménagement et De Gestion du Parc National Cœlacanthe 2017-2021 Janvier 2018 Les avis et opinions exprimés dans ce document sont celles des auteurs, et ne reflètent pas forcément les vues de la Vice Présidence - Ministère de l’Agriculture, de la Pêche, de l’Environnement, de l’Aménagement du Territoire et de l’Urbanisme, ni du PNUD, ni du FEM (UNDP - GEF) Mandaté par L’Union des Comores, Vice-Présidence Chargée du Ministère de l’Agriculture, de la Pêche, de l’Environnement, de l’Aménagement du Territoire et de l’Urbanisme, Parcs nationaux des Comores Et le Programme des Nations Unies pour le Développement, PNUD Fonds Mondial pour l’Environnement, FEM Maison du PNUD, Hamramba BP. 648, Moroni, Union des Comores T +269 7731558/9, F +269 7731577 www.undp.org Titre du Projet d’appui RNAP Développement d’un réseau national d’aires protégées terrestres et marines représentatives du patrimoine naturel unique des Comores et cogérées par les communautés villageoises locales. PIMS : 4950, ID ATLAS : 00090485 Citation : Parcs nationaux des Comores (2017). Plan d’Aménagement et de Gestion du Parc National Cœlacanthe. 2017-2021. 134 p + Annexes 98 p. Pour tous renseignements ou corrections : Lacroix Eric, Consultant international UNDP [email protected] Fouad ABDOU RABI, Coordinateur RNAP [email protected] Plan d’aménagement et de gestion du Parc national Cœlacanthe - 2017 2 Avant-propos Depuis 1994 le souhait des Comoriennes et Comoriens et de leurs amis du monde entier est de mettre en place un Système pour la protection et le développement des aires protégées des Comores. -

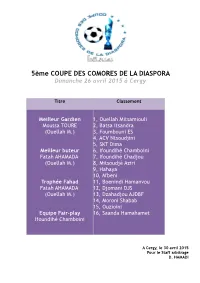

Résultats CCD 5

5ème COUPE DES COMORES DE LA DIASPORA Dimanche 26 avril 2015 à Cergy Titre Classement Meilleur Gardien 1, Ouellah Mitsamiouli Moussa TOURE 2, Batsa Itsandra (Ouellah M.) 3, Foumbouni ES 4, ACV Ntsoudjini 5, SKT Dima Meilleur buteur 6, Ifoundihé Chamboini Fatah AHAMADA 7, Ifoundihé Chadjou (Ouellah M.) 8, Mitsoudjé Aziri 9, Hahaya 10, M'beni Trophée Fahad 11, Boenindi Hamanvou Fatah AHAMADA 12, Djomani DJS (Ouellah M.) 13, Dzahadjou AJDBF 14, Moroni Shabab 15, Ouzioini Equipe Fair-play 16, Saanda Hamahamet Ifoundihé Chamboini A Cergy, le 30 avril 2015 Pour le Staff arbitrage D. HAMADI CCD 2015 / POULE A Tableau des matches Matches Équipes Scores Équipes Foumbouni E-S 2 – 0 AJDBF Dzahadjou Ouzioini 0 – 1 Mitsoudjé AZIRI AJDBF Dzahadjou 0 – 2 Mitsoudjé AZIRI Foumbouni E-S 3 – 0 Ouzioini Foumbouni E-S 2 – 2 Mitsoudjé AZIRI Ouzioini 1 – 1 AJDBF Dzahadjou Tableau des points 1er Match 2ème Match 3ème Match Total Diff. Foumbouni E-S 3 3 1 7 7 AJDBF Dzahadjou 0 0 1 1 / Ouzioini 0 0 1 1 / Mitsoudjé AZIRI 3 3 1 7 5 Rappel : victoire : + 3 / nul : + 1 / défaite : 0 Premier : Foumbouni ES / Deuxième : Mitsoudjé AZIRI CCD 2015 / POULE B Tableau des matches Matches Équipes Scores Équipes Ifoundihé Chamboini 1 – 1 Ifoundihé Chadjou Djomani DJS 1 – 0 Hahaya Ifoundihé Chadjou 0 – 1 Hahaya Djomani DJS 0 – 1 Ifoundihé Chamboini Ifoundihé Chadjou 5 – 2 Djomani DJS Hahaya 0 – 0 Ifoundihé Chamboini Tableau des points 1er Match 2ème Match 3ème Match Total Diff. Ifoundihé Chamboini 1 3 1 5 / Ifoundihé Chadjou 1 0 3 4 6 Djomani DJS 3 0 0 3 3 Hahaya 0 3 1 4 / Rappel : victoire : + 3 / nul : + 1 / défaite : 0 Premier : Ifoundihé Chamboini / Deuxième : Ifoundihé Chadjou CCD 2015 / POULE C Tableau des matches Matches Équipes Scores Équipes Batsa Itsandra 0 – 0 ACV Ntsoudjini Moroni Al-Shabab 2 – 1 Saada Hamahamet ACV Ntsoudjini 2 – 0 Saada Hamahamet Batsa Itsandra 2 – 0 Moroni Al-Shabab Moroni Al-Shabab 1 – 3 ACV Ntsoudjini Saada Hamahamet 0 – 2 Batsa Itsandra Tableau des points 1er Match 2ème Match 3ème Match Total Diff. -

Vol. 22 - Comoros

Marubeni Research Institute 2016/09/02 Sub -Saharan Report Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the focal regions of Global Challenge 2015. These reports are by Mr. Kenshi Tsunemine, an expatriate employee working in Johannesburg with a view across the region. Vol. 22 - Comoros June 10, 2016 It was well known that Marilyn Monroe wore Chanel No. 5 perfume when she went to bed. Did you know that Chanel No. 5’s essence (essential oils) comes from the flower called ylang-ylang, which is found in the African country of Comoros? Comoros is also where the so-called “living fossils”, a rare pre-historic species of fish called coelacanths, discovered in 1938 in South Africa after having thought to be extinct, are mostly found. So this time I would like to introduce the country of Comoros, fascinating like Marilyn Monroe and a little mysterious like the coelacanths. Table 1: Comoros Country Information The Union of the Comoros is an archipelago island nation located off the coast of East Africa east of Mozambique and northwest from Madagascar. 4 main islands make up the Comoros archipelago, Grande Comore, Moheli, Anjouan and Mayotte, with Grande Comore, Moheli, and Anjouan forming the Union of Comoros and Mayotte falling under French jurisdiction as an ‘overseas department” or region. The population of the 3 islands making up the Union of the Comoros is about 800,000, while their total land area comes to 2,236 square kilometers, about the same land size as Tokyo, which makes it quite a small country. Nominal GDP is roughly $600 million, which is second from the bottom among the 45 sub-Saharan African countries, just above Sao Tome and Principe, and its population is the 5th lowest (note 1). -

Eies) Et Plan De Gestion Environnementale Et Sociale (Pges) Du Projet Comoresol – Grandes Comores

UNION DES COMORES Unité – Solidarité – Développement ---------------- MINISTERE DES FINANCES ET DU BUDGET ---------------- PROGRAMME REGIONAL D’INFRASTRUCTURES DE COMMUNICATION RCIP-4 ------ ETUDE D’IMPACT ENVIRONNEMENTAL ET SOCIAL (EIES) ET PLAN DE GESTION ENVIRONNEMENTALE ET SOCIALE (PGES) DU PROJET COMORESOL – GRANDES COMORES Version finale Novembre 2019 SOMMAIRE SOMMAIRE 1 - RESUME EXECUTIF EN FRANCAIS ..................................................................... 7 2 - UFUPIZI WA MTRILIYO NDZIANI .................................................................... 27 3 - CONTEXTE GENERAL, OBJECTIFS ET METHODOLOGIE D’ELABORATION DE L’EIES ........................................................................................................................ 46 4 - BREVE DESCRIPTION DU PROJET ................................................................... 51 5 - CADRE JURIDIQUE ET LES POLITIQUES DE SAUVEGARDE DE LA BANQUE MONDIALE .............................................................................................................. 81 6 - DESCRIPTION ET ANALYSE DE L’ETAT INITIAL DU SITE ET DE SON ENVIRONNEMENT .................................................................................................. 97 7 - CONSULTATION DU PUBLIC .......................................................................... 154 8 - ANALYSE ET EVALUATION DES IMPACTS ENVIRONNEMENTAUX ET SOCIAUX DU PROJET ........................................................................................... 155 ETUDE D’IMPACT ENVIRONNEMENTAL -

Socmon Comoros NOAA

© C3 Madagascar and Indian Ocean Islands Programme 2010 C3 Madagascar and Indian Ocean Islands Programme is a collaborative initiative between Community Centred Conservation (C3), a non-profit company registered in England no. 5606924 and local partner organizations. The study described in this report was funded by the NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program. Suggested citation: C3 Madagascar and Indian Ocean Islands Programme (2010) SOCIO- ECONOMIC ASSESSMENT AND IDENTIFICATION OF POTENTIAL SITES FOR COMMUNITY-BASED CORAL REEF MANAGEMENT IN THE COMOROS. A Report Submitted to the NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program, USA 22pp FOR MORE INFORMATION C3 Madagascar and Indian Ocean NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program Islands Programme (Comoros) Office of Response and Restoration BP8310 Moroni NOAA National Ocean Service Iconi 1305 East-West Highway Union of Comoros Silver Spring, MD 20910 T. +269 773 75 04 USA CORDIO East Africa Community Centred Conservation #9 Kibaki Flats, Kenyatta Beach, (C3) Bamburi Beach www.c-3.org.uk PO BOX 10135 Mombasa 80101, Kenya [email protected] [email protected] Cover photo: Lobster fishers in northern Grande Comore SOCIO-ECONOMIC ASSESSMENT AND IDENTIFICATION OF POTENTIAL SITES FOR COMMUNITY-BASED CORAL REEF MANAGEMENT IN THE COMOROS Edited by Chris Poonian Community Centred Conservation (C3) Moroni 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report is the culmination of the advice, cooperation, hard work and expertise of many people. In particular, acknowledgments are due to the following for their contributions: COMMUNITY CENTRED -

Towards a More United & Prosperous Union of Comoros

TOWARDS A MORE UNITED & PROSPEROUS Public Disclosure Authorized UNION OF COMOROS Systematic Country Diagnostic Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS i CPIA Country Policy and Institutional Assessment CSOs Civil Society Organizations DeMPA Debt Management Performance Assessment DPO Development Policy Operation ECP Economic Citizenship Program EEZ Exclusive Economic Zone EU European Union FDI Foreign Direct Investment GDP Gross Domestic Product GNI Gross National Income HCI Human Capital Index HDI Human Development Index ICT Information and Communication Technologies IDA International Development Association IFC International Finance Corporation IMF International Monetary Fund INRAPE National Institute for Research on Agriculture, Fisheries, and the Environment LICs Low-income Countries MDGs Millennium Development Goals MIDA Migration for Development in Africa MSME Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises NGOs Non-profit Organizations PEFA Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability PPP Public/Private Partnerships R&D Research and Development SADC Southern African Development Community SDGs Sustainable Development Goals SOEs State-Owned Enterprises SSA Sub-Saharan Africa TFP Total Factor Productivity WDI World Development Indicators WTTC World Travel & Tourism Council ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank members of the Comoros Country Team from all Global Practices of the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation, as well as the many stakeholders in Comoros (government authorities, think tanks, academia, and civil society organizations, other development partners), who have contributed to the preparation of this document in a strong collaborative process (see Annex 1). We are grateful for their inputs, knowledge and advice. This report has been prepared by a team led by Carolin Geginat (Program Leader EFI, AFSC2) and Jose Luis Diaz Sanchez (Country Economist, GMTA4). -

UNION DES COMORES Unité – Solidarité – Développement

UNION DES COMORES Unité – Solidarité – Développement --------- ! DIRECTION GENERALE DE L’ANACEP ---------- _________________________________________________ PROJET DE FILETS SOCIAUX DE SECURITES Accord de Financement N° D0320 -KM RAPPORT SEMESTRIEL D’ACTIVITES N° 05 Période du 1 er juillet au 31 décembre 2017 Février 2018 1 SIGLES ET ABREVIATIONS ACTP : Argent Contre Travail Productif ACTC : Argent Contre Travail en réponses aux Catastrophes AG : Assemblée Générale AGEX : Agence d’Exécution ANACEP : Agence Nationale de Conception et d’Exécution des Projets AGP : Agence de Paiement ANO: Avis de Non Objection AVD : Agent Villageois de Développement ANJE : Amélioration du Nourrisson et du Jeune Enfant BE : Bureau d’Etudes BM : Banque Mondiale CCC : Comité Central de Coordination CG : Comité de Gestion CGES : Cadre de Gestion Environnementale et Sociale CGSP : Cellule de Gestion de Sous Projet CI : Consultant Individuel CP : Comité de Pilotage CPR : Cadre de politique de Réinstallation CPS Comité de Protection Sociale CR : Comité Régional DAO : Dossier d’appel d’offre DEN : Directeur Exécutif National DGSC : Direction Générale de la Sécurité Civile DP : Demande de Proposition DER : Directeur Exécutif Régional DNO : Demande de Non Objection DSP : Dossier de sous- projet FFSE : Facilitateur chargé du Suivi Evaluation HIMO : Haute Intensité de Main d’Œuvres IDB : Infrastructure de Bases IDB C : Infrastructure De Base en réponse aux Catastrophes IEC : Information Education et Communication MDP : Mémoire Descriptif du Projet MWL : île de Mohéli -

21 3 223 225 Golovatch Comores.P65

Arthropoda Selecta 21(3): 223225 © ARTHROPODA SELECTA, 2012 New records of millipedes from the Comoro Islands (Diplopoda) Íîâûå íàõîäêè ìíîãîíîæåê-äèïëîïîä ñ Êîìîðñêèõ îñòðîâîâ (Diplopoda) C. Rollard1 & S.I. Golovatch2 Ê. Ðîëëàð1, Ñ.È. Ãîëîâà÷2 1 Muséum national dHistoire naturelle, Département Systématique & Evolution, UMR 7205 OSEB, Section Arthropodes, 57 rue Cuvier, CP 53, 75005 Paris, France. 2 Institute for Problems of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences, Leninsky pr. 33, Moscow 119071, Russia. 2 Èíñòèòóò ïðîáëåì ýêîëîãèè è ýâîëþöèè ÐÀÍ, Ëåíèíñêèé ïð. 33, Ìîñêâà 119071 Ðîññèÿ. KEY WORDS: Diplopoda, fauna, Comoros. ÊËÞ×ÅÂÛÅ ÑËÎÂÀ: Diplopoda, ôàóíà, Êîìîðñêèå îñòðîâà. ABSTRACT. A small collection of diplopods from MW05, Lake Dziani Boundouni, degraded dry forest (60 m), the Comoros contains nine species, two of which repre- 31.10.2008.; 1 juv.: Mohéli, MW16, Chalet St Antoine, natural sent new island records. The fauna (16 species) is forest on crest (700 m), 4.11.2008. confirmed to be depauperate and dominated by anthro- REMARKS. This pantropical species is quite com- pochore species, but several seem to be local endemics mon on all of the islands of the Comoro Archipelago (4) or subendemics (3). [VandenSpiegel & Golovatch, 2007]. ÐÅÇÞÌÅ. Íåáîëüøîé ìàòåðèàë äèïëîïîä ñ Êî- ìîðñêèõ îñòðîâîâ ñîäåðæèò äåâÿòü âèäîâ, äâà èç Family Pachybolidae êîòîðûõ âïåðâûå óêàçàíû äëÿ îäíîãî èç îñòðîâîâ. Ïîäòâåðæäàåòñÿ, ÷òî ôàóíà (16 âèäîâ) îáåäíåíà è â íåé äîìèíèðóþò àíòðîïîõîðíûå âèäû, íî â åå ñî- Leptogoniulus sorornus (Butler, 1876) ñòàâå, î÷åâèäíî, åñòü è ìåñòíûå ýíäåìèêè (4) è ñóáýíäåìèêè (3). MATERIAL. 1 juv.: Anjouan, ND16, Hajoho Bay, back beach, degraded forest (2 m), 16.11.2010; 1 $: Grande Comore, NG01, Mt Dima Kora, Lake Hantsangoma, banana plants (1000 m), Introduction 19.10.2008. -

Arret N°16-016 Primaire Ngazidja

H h ~I'-I courcon5t~liorwr~ UNION DES COMORES Olll\;I\IHliWif,!' Unité - Solidarité - Développement ARRET N° 16-016/E/P/CC PORTANT PROCLAMATION DES RESULTATS DEFINITIFS DE L'ELECTION PRIMAIRE DE L'ILE DE NGAZIDJA La Cour constitutionnelle, VU la Constitution du 23 décembre 200 l, telle que révisée; VU la loi organique n° 04-001/ AU du 30 juin 2004 relative à l'organisation et aux compétences de la Cour constitutionnelle; VU la loi organique n° 05-014/AU du 03 octobre 2005 sur les autres attributions de la Cour constitutionnelle modifiée par la loi organique n° 14-016/AU du 26juin 2014; VU la loi organique n° 05-009/AU du 04 juin 2005 fixant les conditions d'éligibilité du Président de l'Union et les modalités d'application de l'article 13 de la Constitution, modifiée par la loi organ ique n? 10-019/ AU du 06 septembre 2010 ; VU la loi n° 14-004/AU du 12 avril 2014 relative au code électoral; VU le décret n° 15- 184/PR du 23 novembre 2015 portant convocation du corps électoral pour l'élection du Président de l'Union et celles des Gouverneurs des Iles autonomes; VU l'arrêt n? 16-001 /E/CC du 02 janvier 2016 portant liste définitive des candidats à l'élection du Président de l'Union de 2016; VU l'arrêté n° 15- 130/MIIDIICAB du 01 décembre 2015 relatif aux horaires d'ouverture et de fermeture des bureaux de vote pour l'élection du Président de l'Union et celles des Gouverneurs des Iles Autonomes; VU le circulaire n? 16-037/MIIDIICAB du 19 février 2016 relatifau vote par procuration; VU la note circulaire n° 16-038/MIIDIICAB du 19 février -

Annotated UNDP-GEF Project Document Template

United Nations Development Programme Project Document Least Developed Country Fund (LDCF) Project title: Strengthening Comoros resilience against climate change and variability related disaster. Country: Implementing Partner: Management Arrangements: National Implementation Modality Union of Comoros UNDP (NIM) UNDAF/Country Programme Outcome: Outcome 4 – By 2019, the most vulnerable populations ensure their resilience to climate change and crises. UNDP Strategic Plan Output: insert either 1.3, 1.4, 1.5 or 2.5 see item 5 under further information in the opening section of the annotated template UNDP Social and Environmental Screening Category: UNDP Gender Marker: 2. Low Atlas Project ID/Award ID number: 00103394 Atlas Output ID/Project ID number: 00105390 UNDP-GEF PIMS ID number: 5445 GEF ID number: 6912 Planned start date: this is defined as the expected Planned end date: 60 months project document signature date LPAC date: Brief project description: The Union of Comoros (Comoros) is comprised of four islands, namely Ngazidja (or Grande Comore), Mwali (Mohéli), Ndzuani (Anjouan) and Maoré (Mayotte). However, the project will only focus on three of the four islands, excluding Maoré from the project area. Comoros is a small island developing state (SIDS) with a population of ~8000 and is one of the most densely populated countries in Africa. Being a SIDS, the Comoros is characterised by limited resources and poor economic resilience. The Comorian population is predominantly dependent upon subsistence livelihoods based on traditional crops and reliant upon natural resources. Existing land use practices connected to natural resource management are poorly managed resulting in food and water insecurity. Furthermore, because of its geographical position and climatic factors, the Comoros is vulnerable to natural disasters such as tropical storms, floods, rising sea level, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and landslides.