Written Statement on Human Rights Situation in Thailand Based on List of Issues : Thailand.13/04/2005 CCPR/C/84/L/THA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic and Social Council Resolution 1996/31

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Distr. Council GENERAL E/CN.4/2005/NGO/15 27 January 2005 ENGLISH ONLY COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Sixty-first session Item 17 (b) of the provisional agenda PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS: HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS Written statement* submitted by the Asian Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Network (AITPN), a non-governmental organization in special consultative status The Secretary-General has received the following written statement which is circulated in accordance with Economic and Social Council resolution 1996/31. [30 December 2004] * This written statement is issued, unedited, in the language(s) received from the submitting non-governmental organization(s). GE.05-10565 E/CN.4/2005/NGO/15 page 2 In the line of fire: Human Rights Defenders in Thailand The murder of human rights defender, Charoen Wat-aksorn, an opponent of the Bo Nok power plant project on the night of 21 June 2004 has brought into focus the systematic and continuing killings of the human rights defenders in Thailand. Charoen Wat-aksorn led the Love Bo Nok Group against construction of two coal-fired power plants for the last seven years. He was shot dead on his way home after testifying before the Senate committee on social development and human security and the House committee on counter- corruption on the alleged malfeasance of local land officials. He had accused the officials of trying to issue title deeds covering 53 rai of public land in tambon Bo Nok of Muang district to Phuan Wanwongsa, allegedly for a local ''influential person''. He also accused many government officials and influential figures of encroaching on public land. -

รายงานสถิติจังหวัดสุราษฎร์ธานี Surat Thani Provincial Statistical Report

ISSN 1905-8314 2560 2017 รายงานสถิติจังหวัดสุราษฎร์ธานี Surat Thani Provincial Statistical Report สำนักงานสถิติจังหวัดสุราษฎร์ธานี Surat Thani Provincial Statistical Office สำนักงานสถิติแห่งชาติ National Statistical Office รายงานสถิติจังหวัด พ.ศ. 2560 PROVINCIAL STATISTICAL REPORT : 2017 สุราษฎรธานี SURAT THANI สํานกั งานสถิติจังหวัดสุราษฎรธานี SURAT THANI PROVINCIAL STATISTICAL OFFICE สํานักงานสถิติแหงชาติ กระทรวงดิจิทัลเพื่อเศรษฐกิจและสังคม NATIONAL STATISTICAL OFFICE MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY ii หน่วยงานเจ้าของเรื่อง Division-in-Charge ส ำนักงำนสถิติจังหวัดสุรำษฎร์ธำนี Surat Thani Provincial Statistical Office, อ ำเภอเมืองสุรำษฎร์ธำนี Mueang Surat Thani District, จังหวัดสุรำษฎร์ธำนี Surat Thani Provincial. โทร 0 7727 2580 Tel. +66 (0) 7727 2580 โทรสำร 0 7728 3044 Fax: +66 (0) 7728 3044 ไปรษณีย์อิเล็กทรอนิกส์: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] หน่วยงานที่เผยแพร่ Distributed by ส ำนักสถิติพยำกรณ์ Statistical Forecasting Bureau, ส ำนักงำนสถิติแห่งชำติ National Statistical Office, ศูนย์รำชกำรเฉลิมพระเกียรติ ๘๐ พรรษำฯ The Government Complex Commemorating His อำคำรรัฐประศำสนภักดี ชั้น 2 Majesty the King’s 80th birthday Anniversary, ถนนแจ้งวัฒนะ เขตหลักสี่ กทม. 10210 Ratthaprasasanabhakti Building, 2nd Floor. โทร 0 2141 7497 Chaeng watthana Rd., Laksi, โทรสำร 0 2143 8132 Bangkok 10210, THAILAND ไปรษณีย์อิเล็กทรอนิกส์: [email protected] Tel. +66 (0) 2141 7497 Fax: +66 (0) 2143 8132 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.nso.go.th ปีที่จัดพิมพ์ 2560 Published 2017 จัดพิมพ์โดย ส ำนักงำนสถิติจังหวัดสุรำษฎร์ธำนี -

Microsoft Office 2000

SEAFDEC/UNEP/GEF/Thailand/31 Establishment and Operation of a Regional System of Fisheries Refugia in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand TECHNICAL REPORT FISHERIES REFUGIA PROFILE FOR THAILAND: SURAT THANI Ratana Munprasit Praulai Nootmorn Kumpon Loychuen Department of Fisheries Bangkok, Thailand December 2020 SEAFDEC/UNEP/GEF/Thailand/31 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 1 2. SITE NAME ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 3. GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 4. SITE INFORMATION ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 4.1 GEOGRAPHY ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 4.2 HISTORY, POPULATION, SOCIO-ECONOMY ……………………………………………………………….5 4.3 IMPORTANT COASTAL HABITATS IN SURAT THANI………………………………………………..…11 4.4 NUMBERS AND TYPES OF FISHING VESSELS OPERATING IN THE REFUGIA AREA ……..17 4.5 THE CATCHES AND SPECIES SELECTIVITY OF THE PRINCIPAL FISHING GEARS USED FOR BLUE SWIMMING CRAB FISHING …………………………………………………………...19 4.6 THE ROLE OF FISHERIES REFUGIA IN THE PRODUCTION AND ECONOMIC VALUE OF PRIORITY SPECIES ………………………………………………………………………………….. 22 4.7 NUMBER OF FISHERIES COMMUNITY IN THE AREA ……………………………………………….. 23 4.8 EXISTING FISHERIES MANAGEMENT MEASURES IN THE AREA OF THE SITE …………….24 4.9 USAGE OF REFUGIA BY THREATENED AND ENDANGERED MARINE SPECIES ……………30 5. PRIORITY SPECIES INFORMATION ……………………………………………………………………………….. 34 5.1 NAME (COMMON/LOCAL/SCIENTIFIC NAME) ………………………………………………………… 34 5.2 MORPHOLOGY ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. -

Risk Patterns of Lung Cancer Mortality in Northern Thailand

Rankantha et al. BMC Public Health (2018) 18:1138 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6025-1 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Risk patterns of lung cancer mortality in northern Thailand Apinut Rankantha1,2, Imjai Chitapanarux3,4,5, Donsuk Pongnikorn6, Sukon Prasitwattanaseree2, Walaithip Bunyatisai2, Patumrat Sripan3,4,5 and Patrinee Traisathit2,7* Abstract Background: Over the past decade, lung cancers have exhibited a disproportionately high mortality and increasing mortality trend in Thailand, especially in the northern region, and prevention strategies have consequently become more important in this region. Spatial analysis studies may be helpful in guiding any strategy put in place to respond to the risk of lung cancer mortality in specific areas. The aim of our study was to identify risk patterns for lung cancer mortality within the northern region of Thailand. Methods: In the spatial analysis, the relative risk (RR) was used as a measure of the risk of lung cancer mortality in 81 districts of northern Thailand between 2008 and 2017. The RR was estimated according to the Besag-York-Mollié autoregressive spatial model performed using the OpenBUGS routine in the R statistical software package. We presented the overall and gender specific lung cancer mortality risk patterns of the region using the Quantum Geographic Information System. Results: The overall risk of lung cancer mortality was the highest in the west of northern Thailand, especially in the Hang Dong, Doi Lo, and San Pa Tong districts. For both genders, the risk patterns of lung cancer mortality indicated a high risk in the west of northern Thailand, with females being at a higher risk than males. -

Risk Assessment of Agricultural Affected by Climate Change: Central Region of Thailand

International Journal of Applied Computer Technology and Information Systems: Volume 10, No.1, April 2020 - September 2020 Risk Assessment of Agricultural Affected by Climate Change: Central Region of Thailand Pratueng Vongtong1*, Suwut Tumthong2, Wanna Sripetcharaporn3, Praphat klubnual4, Yuwadee Chomdang5, Wannaporn Suthon6 1*,2,3,4,5,6 Faculty of Science and Technology, Rajamangala University of Technology Suvarnabhumi, Ayutthaya, Thailand e-mail: 1*[email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract — The objective of this study are to create a changing climate, the cultivation of Thai economic risk model of agriculture with the Geo Information crops was considerably affected [2] System (GIS) and calculate the Agricultural In addition, the economic impact of global Vulnerability Index ( AVI) in Chainat, Singburi, Ang climate change on rice production in Thailand was Thong and Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya provinces by assessed [3] on the impact of climate change. The selecting factors from the Likelihood Vulnerability results of assessment indicated that climate change Index (LVI) that were relevant to agriculture and the affected the economic dimension of rice production in climate. The data used in the study were during the year Thailand. Both the quantity of production and income 1986-2016 and determined into three main components of farmers. that each of which has a sub-component namely: This study applied the concept of the (1)Exposure -

Contracted Garage

Contracted Garage No Branch Province District Garage Name Truck Contact Number Address 035-615-990, 089- 140/2 Rama 3 Road, Bang Kho Laem Sub-district, Bang Kho Laem District, 1 Headquarters Ang Thong Mueang P Auto Image Co., Ltd. 921-2400 Bangkok, 10120 188 Soi 54 Yaek 4 Rama 2 Road, Samae Dam Sub-district, Bang Khun Thian 2 Headquarters Ang Thong Mueang Thawee Car Care Center Co., Ltd. 035-613-545 District, Bangkok, 10150 02-522-6166-8, 086- 3 Headquarters Bangkok Bang Khen Sathitpon Aotobody Co., Ltd. 102/8 Thung Khru Sub-district, Thung Khru District, Bangkok, 10140 359-7466 02-291-1544, 081- 4 Headquarters Bangkok Bang Kho Laem Au Supphalert Co., Ltd. 375 Phet kasem Road, Tha Phra Sub-district, Bangkok Yai District, Bangkok, 10600 359-2087 02-415-1577, 081- 109/26 Moo 6 Nawamin 74 Road Khlong Kum Sub-district Bueng Kum district 5 Headquarters Bangkok Bang Khun Thian Ch.thanabodyauto Co., Ltd. 428-5084 Bangkok, 10230 02-897-1123-8, 081- 307/201 Charansanitwong Road, Bang Khun Si Sub-district, Bangkok Noi District, 6 Headquarters Bangkok Bang Khun Thian Saharungroj Service (2545) Co., Ltd. 624-5461 Bangkok, 10700 02-896-2992-3, 02- 4/431-3 Moo 1, Soi Sakae Ngam 25, Rama 2 Road, Samae Dam 7 Headquarters Bangkok Bang Khun Thian Auychai Garage Co., Ltd. 451-3715 Sub-district, Bang Khun Thien District, Bangkok, 10150 02-451-6334, 8 Headquarters Bangkok Bang Khun Thian Car Circle and Service Co., Ltd. 495 Hathairat Road, Bang, Khlong Sam Wa District, Bangkok, 10510 02-451-6927-28 02-911-5001-3, 02- 9 Headquarters Bangkok Bang Sue Au Namchai TaoPoon Co., Ltd. -

The Impact of Religious Tourism on Buddhist Monasteries: an Examination of Nine Temples in Ang Thong

THE IMPACT OF RELIGIOUS TOURISM ON BUDDHIST MONASTERIES: AN EXAMINATION OF NINE TEMPLES IN ANG THONG By Mr. Panot Asawachai A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor Of Philosophy Program in Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism International Program Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2016 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University THE IMPACT OF RELIGIOUS TOURISM ON BUDDHIST MONASTERIES: AN EXAMINATION OF NINE TEMPLES IN ANG THONG By Mr. Panot Asawachai A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor Of Philosophy Program in Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism International Program Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2016 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University 55056953 : MAJOR : ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE MANAGEMENT AND TOURISM KEY WORD : TOURISM IMPACT/RELIGIOUS TOURISM/BUDDHIST MONASTERY PANOT ASAWACHAI : THE IMPACT OF RELIGIOUS TOURISM ON BUDDHIST MONASTERIES: AN EXAMINATION OF NINE TEMPLES IN ANG THONG. THESIS ADVISOR: DONALD ELLSMORE, DPhilFAPT. 180 pp. In this dissertation, the impact of religious tourism development on the cultural heritage of sacred Buddhist places is explored through an examination of nine temples in Ang Thong and their communities. The research considers strategies that might permit religious tourism development while conserving the cultural heritage significance of the places. A review of the evolution of tourism development and evaluation of tourism impacts by assessing and studying nine sacred temples’ cultural heritage was undertaken to develop a practicable approach to promoting and managing tourism sustainably. The research reveals that the development and promotion of the nine temples in Ang Thong occurs in two important stages. The first is the emergence of royal monasteries and common temples that reflect the relationship between the religion and society. -

Budgetworldclass Drives

Budget WorldClass Drives Chiang Mai-Sukhothai Loop a m a z i n g 1998 Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) SELF DRIVE VACATIONS THAILAND 1999 NORTHERN THAILAND : CHIANG MAI - SUKHOTHAI AND BURMESE BORDERLANDS To Mae Hong Son To Fang To Chiang Rai To Wang Nua To Chiang Rai 1001 1096 1 107 KHUN YUAM 118 1317 1 SAN KAMPHAENG 1269 19 CHIANG MAI1006 MAE ON 1317 CHAE HOM HANG DONG SARAPHI 108 Doi Inthanon 106 SAN PA TONG 11 LAMPHUN 1009 108 116 MAE CHAEM 103 1156 PA SANG 1035 1031 1033 18 MAE THA Thung Kwian MAE LA NOI 11 Market 1088 CHOM TONG 1010 1 108 Thai Elephant HANG CHAT BAN HONG 1093 Conservation 4 2 1034 Centre 3 LAMPANG 11 To 106 1184 Nan 15 16 HOD Wat Phrathat 1037 LONG 17 MAE SARIANG 108 Lampang Luang KO KHA 14 MAE 11 PHRAE km.219 THA Ban Ton Phung 1103 THUNG 1 5 SUNGMEN HUA SOEM 1099 DOI TAO NGAM 1023 Ban 1194 SOP MOEI CHANG Wiang Kosai DEN CHAI Mae Sam Laep 105 1274 National Park WANG CHIN km.190 Mae Ngao 1125 National Park 1124 LI SOP PRAP OMKOI 1177 101 THOEN LAP LAE UTTARADIT Ban Tha 102 Song Yang Ban Mae Ramoeng MAE SI SATCHANALAI PHRIK 1294 Mae Ngao National Park 1305 6 Mae Salit Historical 101 km.114 11 1048 THUNG Park SAWAN 105 SALIAM 1113 7 KHALOK To THA SONG SAM NGAO 1113 Phitsa- YANG Bhumipol Dam Airport nuloke M Y A N M A R 1056 SI SAMRONG 1113 1195 Sukhothai 101 ( B U R M A ) 1175 9 Ban Tak Historical 1175 Ban 12 Phrathat Ton Kaew 1 Park BAN Kao SUKHOTHAI MAE RAMAT 12 DAN LAN 8 10 105 Taksin 12 HOI Ban Mae Ban National Park Ban Huai KHIRIMAT Lamao 105 TAK 1140 Lahu Kalok 11 105 Phrathat Hin Kiu 13 104 1132 101 12 Hilltribe Lan Sang Miyawadi MAE SOT Development National Park Moei PHRAN KRATAI Bridge 1090 Centre 1 0 10 20 kms. -

Assessments of Public's Perceptions of Their

International Journal of Asian History Culture and Tradition Vol 3, No.2, pp. 21-29, August 2016 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) ASSESSMENTS OF PUBLIC’S PERCEPTIONS OF THEIR SATISFACTIONS TO THEIR PARTICIPATING ACTIVITIES ON THE LOTUS THROWING (RUB BUA) FESTIVAL TOWARD CULTURAL HERITAGE OF BANG PHLI COMMUNITIES IN THE 80TH IN 2015 “ONE OF THE WORLD: ONLY ONE OF THAILAND‖ Maj. Gen. Utid Kotthanoo, Prasit Thongsawai, Daranee Deprasert, and Thitirut Jaiboon Southeast Bangkok College, Bang Na, Bangkok, Thailand 10260 Tel: +66 (0)8 4327 1412 Fax: +66 2 398 1356 ABSTRACT: This research is reported an important of the favorite festivals in Thailand, which is the lotus throwing (Rap Bua) festival in Bang Phli, Samut Prakan. This is basically what happens as countless thousands of local public line the banks of Samrong Canal to throw lotus flowers onto a boat carrying a replica of the famous Buddha image Luang Poh To. The aims of this research are to describe for assessing public’s perceptions of their participants who go to Wat Bang Phli Yai Nai which, for obvious reasons, has the best atmosphere, to compare between public’s perception of their gender of their satisfactions to the entire route from start to finish of the boat carrying the Buddha image wasn’t scheduled to pass the front of Wat Bang Phli Yai Nai toward their participated activities. Associations between public’s participating activities and their satisfied of the lotus throwing (Rap Bua) festival were assessed. Using the qualitative data with interview, observation, and participated memberships’ activities were designed. -

Introduction

Introduction This report, Situation of the Thai Elderly 2019, is a production of the National Commission on Older Persons which has the responsibility to issue this report in accordance with Article 9(10) of the Elderly Act of 2003, and present the findings to the Cabinet each year. Ever since 2006, the National Commission on Older Persons has assigned the Foundation of Thai Gerontology Research and Development Institute (TGRI) to implement this assignment. This edition compiles data and information on older Thai persons for the year 2019, and explores trends in changes of the age structure of the population in the past in order to project the situation of older persons in the future. Each edition of the annual report on the Situation of the Thai Elderly has a particular focus or theme. For example, the 2013 edition focused on income security of older persons, the 2014 issue emphasized the vulnerability of older persons in the event of natural disasters, the 2015 focused on living arrangements of older persons, the 2016 edition focused on the health of the Thai elderly, the 2017 edition explored the concept of active aging in the Thai context of older persons, while the 2018 edition examined Thai elderly and employment. For the current edition (2019), the focus is on the social welfare of the elderly. In one sense, ‘Social Welfare’ sounds like a distant dream or ideal for Thai society, especially given the threat of the country’s being caught in the “middle-income trap.” However, if one considers examples of past policy, whether it is education or public health, Thailand should be able to create a system that covers the priority target groups, reduces the burden, and creates opportunities for people to have a good quality of life. -

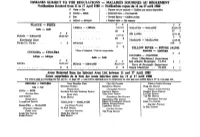

MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received from 11 to 17 April 1980 — Notifications Reçues Dn 11 Au 17 Avril 1980 C Cases — C As

Wkly Epidem. Rec * No. 16 - 18 April 1980 — 118 — Relevé èpidém, hebd. * N° 16 - 18 avril 1980 investigate neonates who had normal eyes. At the last meeting in lement des yeux. La séné de cas étudiés a donc été triée sur le volet December 1979, it was decided that, as the investigation and follow et aucun effort n’a été fait, dans un stade initial, pour examiner les up system has worked well during 1979, a preliminary incidence nouveau-nés dont les yeux ne présentaient aucune anomalie. A la figure of the Eastern District of Glasgow might be released as soon dernière réunion, au mois de décembre 1979, il a été décidé que le as all 1979 cases had been examined, with a view to helping others système d’enquête et de visites de contrôle ultérieures ayant bien to see the problem in perspective, it was, of course, realized that fonctionné durant l’année 1979, il serait peut-être possible de the Eastern District of Glasgow might not be representative of the communiquer un chiffre préliminaire sur l’incidence de la maladie city, or the country as a whole and that further continuing work dans le quartier est de Glasgow dès que tous les cas notifiés en 1979 might be necessary to establish a long-term and overall incidence auraient été examinés, ce qui aiderait à bien situer le problème. On figure. avait bien entendu conscience que le quartier est de Glasgow n ’est peut-être pas représentatif de la ville, ou de l’ensemble du pays et qu’il pourrait être nécessaire de poursuivre les travaux pour établir le chiffre global et à long terme de l’incidence de ces infections. -

Prachuap Khiri Khan

94 ภาคผนวก ค ชื่อจังหวดทั ี่เปนค ําเฉพาะในภาษาอังกฤษ 94 95 ชื่อจังหวัด3 ชื่อจังหวัด Krung Thep Maha Nakhon (Bangkok) กรุงเทพมหานคร Amnat Charoen Province จังหวัดอํานาจเจริญ Angthong Province จังหวัดอางทอง Buriram Province จังหวัดบุรีรัมย Chachoengsao Province จังหวัดฉะเชิงเทรา Chainat Province จังหวัดชัยนาท Chaiyaphom Province จังหวัดชัยภูมิ Chanthaburi Province จังหวัดจันทบุรี Chiang Mai Province จังหวัดเชียงใหม Chiang Rai Province จังหวัดเชียงราย Chonburi Province จังหวัดชลบุรี Chumphon Province จังหวัดชุมพร Kalasin Province จังหวัดกาฬสินธุ Kamphaengphet Province จังหวัดกําแพงเพชร Kanchanaburi Province จังหวัดกาญจนบุรี Khon Kaen Province จังหวัดขอนแกน Krabi Province จังหวัดกระบี่ Lampang Province จังหวัดลําปาง Lamphun Province จังหวัดลําพูน Loei Province จังหวัดเลย Lopburi Province จังหวัดลพบุรี Mae Hong Son Province จังหวัดแมฮองสอน Maha sarakham Province จังหวัดมหาสารคาม Mukdahan Province จังหวัดมุกดาหาร 3 คัดลอกจาก ราชบัณฑิตยสถาน. ลําดับชื่อจังหวัด เขต อําเภอ. คนเมื่อ มีนาคม 10, 2553, คนจาก http://www.royin.go.th/upload/246/FileUpload/1502_3691.pdf 95 96 95 ชื่อจังหวัด3 Nakhon Nayok Province จังหวัดนครนายก ชื่อจังหวัด Nakhon Pathom Province จังหวัดนครปฐม Krung Thep Maha Nakhon (Bangkok) กรุงเทพมหานคร Nakhon Phanom Province จังหวัดนครพนม Amnat Charoen Province จังหวัดอํานาจเจริญ Nakhon Ratchasima Province จังหวัดนครราชสีมา Angthong Province จังหวัดอางทอง Nakhon Sawan Province จังหวัดนครสวรรค Buriram Province จังหวัดบุรีรัมย Nakhon Si Thammarat Province จังหวัดนครศรีธรรมราช Chachoengsao Province จังหวัดฉะเชิงเทรา Nan Province จังหวัดนาน