Saint-Gall, Christchurch and Vallbona De Les Monges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acta De La Sessió Ordinària Celebrada Pel Ple De L’Ajuntament Amb Data 16 De Setembre De 2010

ACTA DE LA SESSIÓ ORDINÀRIA CELEBRADA PEL PLE DE L’AJUNTAMENT AMB DATA 16 DE SETEMBRE DE 2010. NÚM.: 8/2010 A S S I S T E N T S Alcaldessa – Presidenta: TUIXENT, 16 de setembre de 2010 Maria Carme Valls Piera Sent les 17:30 hores del dia assenyalat i sota la Presidència de la Sra. Alcaldessa, assistida per la infrascrita Secretària, van concórrer prèvia citació en forma, els Regidors que al marge s’expressen, i que constitueixen el quòrum suficient, amb l’objecte de celebrar la sessió ordinària, en primera convocatòria, a què fa referència els articles 77 b) i 78.2, del Reglament d’Organització, Funcionament i Règim Jurídic de les Entitats Locals. Regidors: Horaci Botella Soret Alfons Escribano Paz Joan Caserras Canals Jaume Ferrer Baraut Secretària: Mª Teresa Solsona Vila Regidors que han excusat la seva assistència: Cap ORDRE DEL DIA 1.- APROVACIÓ DE L’ ACTA DE LA SESSIÓ ANTERIOR. TRÀMIT I ESTAT D’EXPEDIENTS 2.-DESISTIR, SI S’ESCAU, DE LA TRAMITACIÓ DE DEU MODIFICACIONS PUNTUALS DE LES NORMES SUBSIDIÀRIES DE PLANEJAMENT EN EL NUCLI DE JOSA DE CADÍ DEL MUNICIPI DE JOSA I TUIXÉN (EXP. AJUNTAMENT NÚM. NNSS 1-2009, EXP. URBANISME NÚM. 2009/038660/L ). 3.- APROVAR L’INFORME DE SOSTENIBILITAT ECONÒMICA REFERENT A LA MODIFICACIÓ PUNTUAL DE LES NORMES SUBSIDIÀRIES DE PLANEJAMENT DEL MUNICIPI DE JOSA I TUIXÉN (EXP. AJUNTAMENT NÚM. NNSS 2-2009, EXP. URBANISME NÚM. 2010/039545/L). 4.- ADAPTACIÓ DEL PRESSUPOST DE LICITACIÓ AL NOU TIPUS D’IVA DE L’OBRA " ARBORÈTUM ALS PLANELLS DEL SASTRÓ”. 5.- ADJUDICACIÓ D’UN CONTRACTE MENOR PER A LA OBRA TITULADA " ARBORÈTUM ALS PLANELLS DEL SASTRÓ”. -

La Inventariació Dels Arxius Municipals De Les Comarques De La Noguera, La

Revista Catalana d'Arxivística LLIGALiyS (1992) LA INVENTARIACIÓ DELS ARXIUS MUNICIPALS DE LES COMARQUES DE LA NOGUERA, LA SEGARRA I L'URGELL Joan Farré i Viladrich (Arxiu Històric Comarcal de Balaguer) Gener Gonzalvo i Bou (Arxiu Històric Comarcal de Tàrrega) Dolors Montagut i Balcells (Arxiu Històric Comarcal de Cervera) Introducció boració dels inventaris dels arxius munici- pals s'inicià simultàniament a les comarques Amb la creació de la Xarxa d'Arxius de l'Urgell, la Noguera, l'Alt UrgeU, el Històrics Comarcals (Llei d'Arxius de Cata- Segrià i la Segarra. Una part dels arxius lunya 6/1985, de 26 d'abril), i el Decret municipals del Pla d'Urgell foren visitats i que en regula la seva organització (Decret inventariats des de Balaguer, Lleida i Tàr- d'Organització de la Xarxa d'Arxius Histò- rega, ja que aleshores no estava creada ofi- rics Comarcals, 110/1988, de 5 de cialment la nova comarca. maig) ^ s'atribueix a aquests arxius la El projecte va rebre un important recol- tutela, protecció, conservació i difusió del zament per part de la Diputació de Lleida, patrimoni documental de la comarca. Es en institució que es va fer càrrec de la contrac- aquest context on hem d'emmarcar el pro- tació de dos llicenciats en història per a cada grama de treball establert i coordinat pel arxiu comarcal (AHC de Balaguer, AHC de Servei d'Arxius de la Generalitat de Cata- la Seu d'UrgeU, AHC de Tàrrega, AHC de lunya, d'inventariació dels fons documen- Cervera, i Arxiu Històric de Lleida). La tals municipals de les comarques de Lleida, mateixa institució va dotar els arxius comar- dins un projecte més ampli d'inventari dels cals d'equips informàtics que han permès arxius municipals de Catalunya^. -

Wine Tourism in Catalonia Catalonia: Table of Contents Tourism Brands

Wine Tourism in Catalonia Catalonia: Table of Contents tourism brands 03 05 06 08 12 Welcome Catalonia is 12 Appellations DO Alella DO Catalunya France to Catalonia wine tourism (DO) Roses 16 20 24 28 32 Girona Costa Brava DO Cava DO Conca de DO Costers DO Empordà DO Montsant Girona Barberà del Segre Paisatges Barcelona Palamós Lleida Alguaire Lleida Barcelona 36 40 44 48 52 DO Penedès DO Pla de Bages DOQ Priorat DO Tarragona DO Terra Alta Barcelona El Prat Camp de Tarragona Reus Tarragona Mediterranean Sea 56 58 60 Distance between capitals A Glossary of Gastronomy Directory and BarcelonaGirona Lleida Tarragona wine and flavors information Km Catalonia Barcelona 107 162 99 Airport Girona 107 255 197 Port Lleida 162 255 101 High-speed train Tarragona 99 197 101 www.catalunya.com Catalonia Catalonia is a Mediterranean destination with an age-old history, a deep-rooted linguistic heritage and a great cultural and natural heritage. In its four regional capitals – Barcelona, Girona, Lleida and Tarragona – you will find a combination of historic areas, medieval buildings, modernist architecture and a great variety of museums. Inland cities, such as Tortosa, Vic or Vilafranca del Penedès, have succeeded in preserving the heritage of their monuments extremely well. With its 580 kms of coastline, the Catalan Pyrenees, many natural parks and protected areas, Catalonia offers a touristic destination full of variety, for all tastes and ages, all year round: family tourism, culture, adventure, nature, business trips, and over 300 wineries open to visitors to delight in the pleasures of wine tourism. Welcome! www.catalunya.com 3 We are about to embark on a Our journey begins in the vineyard, a world filled wonderful journey with different varieties of through the world grapes, home to seasonal Catalonia: of wine, a cultural activities and marked by all aspects of rural and the essence of wine tourism adventure, filled agricultural life, which all with aromas contribute to making and emotions, the magic of a journey called wine possible. -

Secció De Senders Ae Talaia

A.E. Talaia SSD20170205 _314 SECCIÓ DE SENDERS AE TALAIA PER LES TERRES DE PONENT Etapa 1 : VALLBONA DE LES MONGES ELS OMELLS DE NA GAIA – SENAN – FULLEDA 5 de febrer de 201 7 HORARI PREVIST Sortida de la Plaça de l’ Estació de Vil a nova i la Geltrú. 7 h Vallbona de les Monges . Esmorzar. 8 h 3 0 min Inici de l’etapa . 9 h Els Omells de na Gaia . Reagrupament. 10 h 1 0 min 10 h 30 min Senan . Reagrupament. 11 h 2 5 min 11 h 3 5 min Parc eòlic de Vilobí . Reagrupament . 12 h 20 min 12 h 30 min Fulleda . Final de l’etapa . 13 h 50 min Sortida cap a Montblanc. 14 h Montblanc . Din ar. 14 h 40 min Sortida cap a Vilanova. 17 h Vilanova i la Geltrú . 18 h 15 min Notes . - ** Esmorzarem a l Cafè Local Social de Vallbona de les Monges . Dinarem a M ontblanc ; hi ha re s taurants . ** Tingueu en compte que l’organització sempre pot modificar aquesta previsió d’horari en funció de com es vagi desenvolupant l’etapa (Condicions meteorològiques, retards o avançaments impr e vistos, etc). ** Si us plau, sigueu p untuals, respecteu els reagrupaments i mantingueu sempre contacte visual amb els que us segueixen; si cal espereu - vos. Intenteu seguir els horaris previstos, és a dir, no correu ni aneu massa lents ! (Pe n seu que aneu en grup). ** Atenció : Per a qualsevol co municació amb la Secció el dissabte abans de l’excursió o el mateix diumenge (mi t- ja hora abans de la sortida) utili t zeu només el telèfon 609862417 ( Manel Vidal ) . -

L'urgell 1.- Recursos Turístics 2.- Productes Turístics 1.- Recursos Turístics

Inventari Turístic. L'URGELL 1.- RECURSOS TURÍSTICS 2.- PRODUCTES TURÍSTICS 1.- RECURSOS TURÍSTICS TIPOLOGIA DE TURISME RECURSOS TURÍSTICS LOCALITZACIÓ NATURA/ESPAIS NATURALS Anglesola - Vilagrassa NATURA/ESPAIS NATURALS Granyena NATURA/ESPAIS NATURALS Plans de Sió NATURA/ESPAIS NATURALS Secans de Belianes - Preixana NATURA/ESPAIS NATURALS Serra de Bellmunt- Almenara NATURA/ESPAIS NATURALS Valls del Sió-Llobregós NATURA / AIGUA Barranc de la Figuerosa Tàrrega NATURA / AIGUA Coladors de Boldú La Fuliola NATURA / AIGUA Llacuna de Claravalls Tàrrega NATURA / AIGUA Salades de Conill Ossó de Sió, Tàrrega NATURA/FAMILIAR Parc de la Font Vella Maldà NATURA/FAMILIAR Parc de Montalbà Preixana NATURA/GEOLOGIA Pedreres del Talladell El Talladell CULTURA/ARQUEOLOGIA/BRONZE FINAL Necròpolis d'Almenara Almenara Alta CULTURA/ARQUEOLOGIA/IBERS Poblat ibèric dels Estinclells Verdú CULTURA/ARQUEOLOGIA/IBERS Poblat ibèric del Molí d'Espígol Tornabous CULTURA/ARQUEOLOGIA/ROMÀ Vil·la romana dels Reguers Puigverd d'Agramunt CULTURA/ARQUEOLOGIA/ROMÀ necròpolis romana Nalec CULTURAL / RELIGIÓS/ROMÀNIC Església de Santa Maria Agramunt CULTURA/RELIGIÓS/ROMÀNIC Església de Sant Pere Castellnou d'Ossó CULTURA/RELIGIÓS/ROMÀNIC Església de Sant Pere Maldà CULTURA/RELIGIÓS/ROMÀNIC Església de la Mare de Déu del Remei Ossó de Sió CULTURA/RELIGIÓS/ROMÀNIC Ermita de Sant Miquel Puigverd d'Agramunt CULTURA/RELIGIÓS/ROMÀNIC Església de Sant Gil Riudovelles CULTURA/RELIGIÓS/ROMÀNIC-GÒTIC-SXIX/CISTER Ermita de la Mare de Déu del Pedregal El Talladell CULTURA/RELIGIÓS/ROMÀNIC-XVIII -

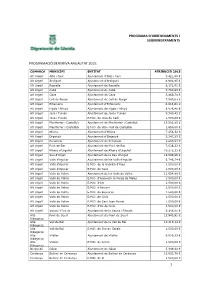

Edicte Programació Definitiva PAS 2015

PROGRAMA D’ARRENDAMENTS I SUBMINISTRAMENTS PROGRAMACIÓ DEFINTIVA ANUALITAT 2015: COMARCA MUNICIPI ENTITAT ATRIBUCIÓ 2015 Alt Urgell Alàs i Cerc Ajuntament d'Alàs i Cerc 7.421,88 € Alt Urgell Arsèguel Ajuntament d'Arsèguel 4.906,95 € Alt Urgell Bassella Ajuntament de Bassella 8.172,81 € Alt Urgell Cabó Ajuntament de Cabó 5.760,63 € Alt Urgell Cava Ajuntament de Cava 5.469,74 € Alt Urgell Coll de Nargó Ajuntament de Coll de Nargó 7.945,09 € Alt Urgell Estamariu Ajuntament d'Estamariu 4.614,61 € Alt Urgell Fígols i Alinyà Ajuntament de Fígols i Alinyà 6.876,45 € Alt Urgell Josa i Tuixén Ajuntament de Josa i Tuixén 5.340,43 € Alt Urgell Josa i Tuixén E.M.D. de Josa de Cadí 1.500,00 € Alt Urgell Montferrer i Castellbò Ajuntament de Montferrer i Castellbò 15.502,85 € Alt Urgell Montferrer i Castellbò E.M.D. de Vila i Vall de Castellbò 1.650,00 € Alt Urgell Oliana Ajuntament d'Oliana 7.256,32 € Alt Urgell Organyà Ajuntament d'Organyà 5.347,23 € Alt Urgell Peramola Ajuntament de Peramola 6.655,97 € Alt Urgell Pont de Bar Ajuntament del Pont de Bar 7.528,32 € Alt Urgell Ribera d'Urgellet Ajuntament de Ribera d'Urgellet 10.275,32 € Alt Urgell Seu d'Urgell Ajuntament de la Seu d'Urgell 19.599,26 € Alt Urgell Valls d'Aguilar Ajuntament de les Valls d'Aguilar 9.746,74 € Alt Urgell Valls d'Aguilar E.M.D. de la Guàrdia d'Ares 1.500,00 € Alt Urgell Valls d'Aguilar E.M.D. -

DEFINITIU INTERIOR O.K.Indd

Com podem observar els quatre monestirs mai no arribaren ELS CAMINS DELS MONESTIRS a ser coetanis alhora: Guiu Sanfeliu Rochet - De 1176 a 1195, Vallbona i el Pedregal. Historiador del Grup de Recerques de les Terres de Ponent - De 1195 a 1237, Vallbona, el Pedregal i la Bovera. Article publicat a: Els monestirs cistercencs de la vall del Corb. - De 1237 a 1589, Vallbona, el Pedregal i Vallsanta. Pàgs. 11-16. Edició del Grup de Recerques de les Terres de - De 1589 a 1604, Vallbona i el Pedregal. Ponent, 1989. - De 1604 fins avui, Vallbona. El motiu del present treball no és altre que situar aquesta zona de la baixa Segarra en el marc geogràfic on es desenvolupen els Els camins i els monestirs treballs sobres els monestirs cistercencs femenins de la vall del riu Corb: amb Vallbona de les Monges, el Pedregal, la Bovera i Si observem atentament el mapa adjunt veurem com els Vallsanta. A partir d’un breu estudi sobre els antics camins que nostres avantpassats a l’hora de traçar un camí varen optar podien utilitzar-se per relacionar-se entre si els diversos monestirs de fer-lo senzill, pel fet que el camí més curt entre dos cistercencs de la comarca. pobles és la línia recta. Així podem observar com tots els camins antics són radials Breu inici sobre els monestirs de poble a poble i que gairebé tots els pobles es comuni- quen amb els seus veïns, per petits que siguin. VALLBONA: comença amb unes agrupacions mixtes d’ermitans, que practicaven la regla benedictina al sud de No obstant, hi ha pobles en els quals hi convergeixen més la Baixa Segarra, de la qual en tenim notícies des de 1153 a camins que no pas en uns altres, és cert, però això sempre 1175. -

BOE 230 De 25/09/2007 Sec 5 Pag 11198 a 11199

11198 Martes 25 septiembre 2007 BOE núm. 230 Término Municipal de Orihuela: Finca número 305-306: Don Miguel Ángel Villar COMUNIDAD AUTÓNOMA Finca número 211-212: Don Pedro Nicolás García, Paya, Citación: Día 7 de noviembre de 2007 a las trece Citación: Día 30 de octubre de 2007 a las nueve horas y horas y veinte minutos. DE CATALUÑA veinte minutos. Finca número 307-308-310: Don Manuel Nicolás Finca número 214-215: D. José Verdú Mazón Y D. García, Citación: Día 7 de noviembre de 2007 a las diez 57.774/07. Resolución de la Generalitat de Cata- José Verdú Rocamora, Citación: Día 30 de octubre de horas y cuarenta minutos. lunya, Departamento de Economía y Finanzas, 2007 a las nueve horas y veinte minutos. Finca número 311: Don Antonio Francisco Cabrera Dirección General de Energía y Minas, de 8 de Finca número 217: Doña Carmen Pacheco Verdú, Álvarez, Citación: Día 7 de noviembre de 2007 a las agosto de 2007, por la que se otorga a la empresa Citación: Día 30 de octubre de 2007 a las diez horas. dieciséis horas y treinta minutos. Acciona Energía, S.A., la autorización adminis- Finca número 218: Doña Carmen Mateo Rocamora, Finca número 312-315-319-320-327-330: Don Anto- trativa, la declaración en concreto de utilidad Citación: Día 30 de octubre de 2007 a las diez horas. nio Cabrera Juárez, Citación: Día 7 de noviembre de pública y la aprobación del proyecto de ejecución Finca número 219: Doña Remedios Mateo Rocamora, 2007 a las dieciséis horas y treinta minutos. -

Actes Dont La Publication Est Une Condition De Leur Applicabilité)

30 . 9 . 88 Journal officiel des Communautés européennes N0 L 270/ 1 I (Actes dont la publication est une condition de leur applicabilité) RÈGLEMENT (CEE) N° 2984/88 DE LA COMMISSION du 21 septembre 1988 fixant les rendements en olives et en huile pour la campagne 1987/1988 en Italie, en Espagne et au Portugal LA COMMISSION DES COMMUNAUTÉS EUROPÉENNES, considérant que, compte tenu des donnees reçues, il y a lieu de fixer les rendements en Italie, en Espagne et au vu le traité instituant la Communauté économique euro Portugal comme indiqué en annexe I ; péenne, considérant que les mesures prévues au présent règlement sont conformes à l'avis du comité de gestion des matières vu le règlement n0 136/66/CEE du Conseil, du 22 grasses, septembre 1966, portant établissement d'une organisation commune des marchés dans le secteur des matières grasses ('), modifié en dernier lieu par le règlement (CEE) A ARRÊTÉ LE PRESENT REGLEMENT : n0 2210/88 (2), vu le règlement (CEE) n0 2261 /84 du Conseil , du 17 Article premier juillet 1984, arrêtant les règles générales relatives à l'octroi de l'aide à la production d'huile d'olive , et aux organisa 1 . En Italie, en Espagne et au Portugal, pour la tions de producteurs (3), modifié en dernier lieu par le campagne 1987/ 1988 , les rendements en olives et en règlement (CEE) n° 892/88 (4), et notamment son article huile ainsi que les zones de production y afférentes sont 19 , fixés à l'annexe I. 2 . La délimitation des zones de production fait l'objet considérant que, aux fins de l'octroi de l'aide à la produc de l'annexe II . -

69 Quadres Dels Municipis De La Demarcació De Lleida

QUADRES DELS MUNICIPIS DE LA DEMARCACIÓ DE LLEIDA CODI INE NOM MUNICIPI QUADRE 25001 Abella de la Conca E 25002 Àger D4 25003 Agramunt D4 25038 Aitona D4 25004 Alamús, els D4 25005 Alàs i Cerc D4 25006 Albagés, l' E 25007 Albatàrrec D3 25008 Albesa E 25009 Albi, l' E 25010 Alcanó E 25011 Alcarràs D4 25012 Alcoletge D4 25013 Alfarràs D4 25014 Alfés E 25015 Algerri E 25016 Alguaire D4 25017 Alins D1 25019 Almacelles D4 25020 Almatret E 25021 Almenar D4 25022 Alòs de Balaguer E 25023 Alpicat D2 25024 Alt Àneu D1 25027 Anglesola D4 25029 Arbeca E 25031 Arres D2 25032 Arsèguel D4 25033 Artesa de Lleida D4 25034 Artesa de Segre D3 25036 Aspa E 25037 Avellanes i Santa Linya, les E 25039 Baix Pallars D3 25040 Balaguer D3 25041 Barbens E 25042 Baronia de Rialb, la E 25044 Bassella E 25045 Bausen D2 25046 Belianes E 25170 Bellaguarda E 25047 Bellcaire d'Urgell E 25048 Bell-lloc d'Urgell D4 25049 Bellmunt d'Urgell E 25050 Bellpuig D4 25051 Bellver de Cerdanya C3 25052 Bellvís E 25053 Benavent de Segrià D4 25055 Biosca E 25057 Bòrdes, es C4 25058 Borges Blanques, les D4 25059 Bossòst C2 25056 Bovera E 25060 Cabanabona E 25061 Cabó E 25062 Camarasa E 69 CODI INE NOM MUNICIPI QUADRE 25063 Canejan D2 25904 Castell de Mur E 25064 Castellar de la Ribera E 25067 Castelldans E 25068 Castellnou de Seana E 25069 Castelló de Farfanya E 25070 Castellserà E 25071 Cava E 25072 Cervera D3 25073 Cervià de les Garrigues E 25074 Ciutadilla E 25075 Clariana de Cardener E 25076 Cogul, el E 25077 Coll de Nargó D4 25163 Coma i la Pedra, la D4 25161 Conca de Dalt E 25078 -

Dossier De Premsa

elprojecte Viles Florides és una iniciativa de la Confederació d’Horticultura Ornamental de Catalunya(CHOC) que promou la transformació de racons, pobles i ciutats de Ca- talunya a través de la flor i la planta ornamental. Aquest moviment pretén mostrar i posar en valor la riquesa natural i paisatgística del país mitjançant el reconeixe- ment públic de tots aquells projectes d’enjardinament, ornamentació floral i cultura del verd urbà que, tant en l’àmbit públic com privat, esdevinguin un exemple a seguir Per Viles Florides l’ornamentació va més enllà de pro- piciar espais agradables i posa en valor la protecció Viles Florides dels espais verds, la millora de la qualitat de vida, la promou la flor i conscienciació social vers polítiques sostenibles o el planta com a desenvolupament d’economies locals a través de patrimoni natural de l’atractiu del parcs i jardins. Catalunya i posa en El projecte és obert a tothom i poden participar-hi els valor polítiques municipis, a nivell institucional, així com qualsevol sostenibles col·lectiu, empresa o particular amb sensibilitat vers la natura i la cura dels espais verds. Un jurat especialitzat format per professionals dels En l’edició 2019, Viles sectors del viverisme, la jardineria, el paisatgisme i Florides lliura per altres àmbits relacionats és l’encarregat de renovar primera vegada la anualment els distintius. La Flor d’Honor –n’hi ha Flor d’Or, un d’una a cinc– és allò que els certifica. En l’edició de reconeixement al 2019, de les 135 Viles Florides que hi ha a Cataluya,, municipi que millor ha n’hi ha 13 amb 4 Flors d’Honor; 53 amb tres Flors treballat durant l’any d’Honor, 57 municipis amb dues i 10 municipis més amb una Flor d’Honor. -

Censo Clubes Lerida.Pdf

Column1 Column3 Column4 Column5 Column6 Column14 Listado Sociedades Código Nombre Sociedad Dirección Sociedad C.P Población Reg. Aut. 250001 SOCIETAT DE CAÇADORS "VALL D' AGER" C/. LA FONT, 9 25691 AGER (LLEIDA) 07754 250002 SOCIETAT CAÇADORS D' AGRAMUNT I COMARCA C/. SIO, 21 25310 AGRAMUNT (LLEIDA) 03298 250003 SOCIETAT DE CAÇADORS LA UNION DE AITONA C/. REMOLINS, 8 25182 AITONA (LLEIDA) 04743 250004 SOCIETAT DE CAÇADORS ALBESA C/. MAJOR, 14 Ajuntament 25135 ALBESA (LLEIDA) 07223 250005 SOCIETAT CAÇADORS D' ALCARRAS C/. BAIX, 37 3a PLANTA 25180 ALCARRAS (LLEIDA) 04741 250006 SOCIETAT DE CAÇADORS D' ALCOLETGE PARTIDA MIRALBO, 65 1er A 25660 ALCOLETGE (LLEIDA) 08762 250007 SOCIETAT DE CAÇADORS EL GAVILAN AV. DE CATALUNYA, 16 AJUNTAMENT 25120 ALFARRAS (LLEIDA) 03634 250008 SOCIETAT CAÇADORS SANT FAUSTO D'ALGUAIRE PLAÇA DE L' ESGLESIA, 21 25125 ALGUAIRE (LLEIDA) 03304 250009 SOCIETAT DE CAÇADORS ALMACELLES C/. JOAQUIM COSTA, 37 25100 ALMACELLES (LLEIDA) 10495 250010 SOCIETAT DE CAÇADORS D' ALMATRET C/. TORT, 28 25187 ALMATRET (LLEIDA) 04988 250011 SOCIETAT DE CAÇADORS ALMENAR C/. ESPADOS, 2n 3a 25126 ALMENAR (LLEIDA) 03192 250012 SOCIETAT DE CAÇADORS D' ANGLESOLA C/. MAJOR, 5 25320 ANGLESOLA (LLEIDA) 04775 250013 SOCIETAT DE CAÇADORS ROC DEL CUDOS C/. MARINO, 16 25617 LA RAPITA (LLEIDA) 03582 250014 ST. DE CAÇADORS SANT MIQUEL DE BELL-LLOC C/. URGELL, 15 BAIXOS 25220 BELL-LLOC (LLEIDA) 03295 250015 STAT. DE CAÇADORS RIBERA DE L' URGELLET C/. MAJOR, 7 CAL PASTISSER 25796 EL PLA DE SANT TIRS (LLEIDA) 07868 250016 ASSOCIACIO DE CAÇA D' ALFES C/. VERGE DE MONTSERRAT, 10 25161 ALFES 09821 250017 SOCIETAT DE CAÇADORS LA BATLLIA CA LES MONGES C/.