The Din-I-Ilahi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philadelphia and the Southern Elite: Class, Kinship, and Culture in Antebellum America

PHILADELPHIA AND THE SOUTHERN ELITE: CLASS, KINSHIP, AND CULTURE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA BY DANIEL KILBRIDE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In seeing this dissertation to completion I have accumulated a host of debts and obligation it is now my privilege to acknowledge. In Philadelphia I must thank the staff of the American Philosophical Society library for patiently walking out box after box of Society archives and miscellaneous manuscripts. In particular I must thank Beth Carroll- Horrocks and Rita Dockery in the manuscript room. Roy Goodman in the Library’s reference room provided invaluable assistance in tracking down secondary material and biographical information. Roy is also a matchless authority on college football nicknames. From the Society’s historian, Whitfield Bell, Jr., I received encouragement, suggestions, and great leads. At the Library Company of Philadelphia, Jim Green and Phil Lapansky deserve special thanks for the suggestions and support. Most of the research for this study took place in southern archives where the region’s traditions of hospitality still live on. The staff of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History provided cheerful assistance in my first stages of manuscript research. The staffs of the Filson Club Historical Library in Louisville and the Special Collections room at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond were also accommodating. Special thanks go out to the men and women at the three repositories at which the bulk of my research was conducted: the Special Collections Library at Duke University, the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the Virginia Historical Society. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90b9h1rs Author Sriram, Pallavi Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Pallavi Sriram 2017 Copyright by Pallavi Sriram 2017 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel by Pallavi Sriram Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Janet M. O’Shea, Chair This dissertation presents a critical examination of dance and multiple movements across the Coromandel in a pivotal period: the long eighteenth century. On the eve of British colonialism, this period was one of profound political and economic shifts; new princely states and ruling elite defined themselves in the wake of Mughal expansion and decline, weakening Nayak states in the south, the emergence of several European trading companies as political stakeholders and a series of fiscal crises. In the midst of this rapidly changing landscape, new performance paradigms emerged defined by hybrid repertoires, focus on structure and contingent relationships to space and place – giving rise to what we understand today as classical south Indian dance. Far from stable or isolated tradition fixed in space and place, I argue that dance as choreographic ii practice, theorization and representation were central to the negotiation of changing geopolitics, urban milieus and individual mobility. -

Volume 7: Shaping Global Islamic Discourses : the Role of Al-Azhar, Al-Medina and Al-Mustafa Masooda Bano Editor

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eCommons@AKU eCommons@AKU Exploring Muslim Contexts ISMC Series 3-2015 Volume 7: Shaping Global Islamic Discourses : The Role of al-Azhar, al-Medina and al-Mustafa Masooda Bano Editor Keiko Sakurai Editor Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_emc Recommended Citation Bano, M. , Sakurai, K. (Eds.). (2015). Volume 7: Shaping Global Islamic Discourses : The Role of al-Azhar, al-Medina and al-Mustafa Vol. 7, p. 242. Available at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_emc/9 Shaping Global Islamic Discourses Exploring Muslim Contexts Series Editor: Farouk Topan Books in the series include Development Models in Muslim Contexts: Chinese, “Islamic” and Neo-liberal Alternatives Edited by Robert Springborg The Challenge of Pluralism: Paradigms from Muslim Contexts Edited by Abdou Filali-Ansary and Sikeena Karmali Ahmed Ethnographies of Islam: Ritual Performances and Everyday Practices Edited by Badouin Dupret, Thomas Pierret, Paulo Pinto and Kathryn Spellman-Poots Cosmopolitanisms in Muslim Contexts: Perspectives from the Past Edited by Derryl MacLean and Sikeena Karmali Ahmed Genealogy and Knowledge in Muslim Societies: Understanding the Past Edited by Sarah Bowen Savant and Helena de Felipe Contemporary Islamic Law in Indonesia: Shariah and Legal Pluralism Arskal Salim Shaping Global Islamic Discourses: The Role of al-Azhar, al-Medina and al-Mustafa Edited by Masooda Bano and Keiko Sakurai www.euppublishing.com/series/ecmc -

The University of North Texas Two O'clock Lab Band the Transparent Two Mp3, Flac, Wma

The University Of North Texas Two O'Clock Lab Band The Transparent Two mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: The Transparent Two Country: US Released: 1994 Style: Big Band MP3 version RAR size: 1606 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1645 mb WMA version RAR size: 1431 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 390 Other Formats: XM VQF MIDI AC3 AA DXD MP4 Tracklist Hide Credits Give And Take 1 Composed By – Denis DiBlasioSoloist, Drums [Drumset] – Greg Beck Soloist, Tenor 4:43 Saxophone – Russ Nolan Art Of The Big Band 2 Composed By – Bob MintzerSoloist, Drums [Drumset] – Don MeoliSoloist, Tenor Saxophone 6:28 – Tyler Kuebler The Poet 3 Composed By – Michael LovelessSoloist, Piano – Tim Harrison Soloist, Tenor Saxophone – 7:31 Jay Miglia Mr. Fonebone 4 Composed By – Bob MintzerSoloist, Drums [Drumet] – Don MeoliSoloist, Tenor Saxophone 4:26 – Tyler Kuebler I Get Along Without You Very Well (Except Sometimes) 5 Arranged By – Bill MathieuSoloist, Alto Saxophone – Bruce BohnstengelSoloist, Trombone – 4:58 Aric SchnellerSoloist, Trumpet – Scott HarrellWritten-By – Hoagy Carmichael Falling In Love With Love 6 Arranged By – Mike HeathmanSoloist, Trumpet – Scott HarrellWritten-By – Richard Rogers 2:26 & Lorenz Hart* Time For A Change 7 5:09 Composed By – Hank LevySoloist, Tenor Saxophone – Tom Hayes Limehouse Blues Arranged By – Bill HolmanSoloist, Alto Saxophone – Alan BurtonSoloist, Drums [Drumset] – 8 3:47 Don MeoliSoloist, Tenor Saxophone – Tyler KueblerSoloist, Trumpet – Steffan Kuehn*Written-By – D. Furber*, P. Braham* What Is This Thing Called -

Greg Hopkins Okavongo Mp3, Flac, Wma

Greg Hopkins Okavongo mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Okavongo Country: US Released: 2001 Style: Big Band MP3 version RAR size: 1136 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1772 mb WMA version RAR size: 1509 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 474 Other Formats: AC3 VQF MOD MP1 FLAC VOX MP4 Tracklist 1 Stretchin' 8:14 2 Okavongo 8:05 3 Contra Part 1 5:33 4 Contra Part 2 4:13 5 Nightfall 6:35 6 Crackdown-Dialogue 1:57 7 Crackdown 6:22 8 Infant Eyes 6:56 9 Sphere Of T.M. Part 1 3:45 10 Sphere Of T.M. Part 2 5:43 11 Thoughts 6:58 12 Steller-Prologue 2:29 13 Steller By Satelite 4:43 Credits Bass – Bruce Gertz, Paul Del Nero Bass Clarinet, Baritone Saxophone – Marc Phaneuf, Tommy Ferrante Drums – Joe Hunt Flugelhorn, Trumpet – George Zance, Jeff Stout Flute, Alto Saxophone – Bruce Nifong, Larry Monroe, Mark Pinto Flute, Soprano Saxophone, Tenor Saxophone – John Griener Guitar – Mick Goodrick Piano – Chris Neville, James Williams , Tim Ray Soprano Saxophone, Tenor Saxophone – Billy Pierce Trombone – Don Gorder, Jeff Galindo, Jerry Ash , Rick Stepton, Tim Kelly , Tony Lada Trumpet, Flugelhorn – John Daly , Paul Fontaine, Scot DeOgburn Notes The full name of the band is "The Greg Hopkins 16 Piece" Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 9940229392 9 Related Music albums to Okavongo by Greg Hopkins 1. The Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra - Heart And Soul 2. Art Ensemble Of Chicago - Live Part 1 3. Brussels Jazz Orchestra - Naked In The Cosmos 4. The University Of Illinois Jazz Band Directed By John Garvey - Déjà Vu 5. -

Europe (In Theory)

EUROPE (IN THEORY) ∫ 2007 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Minion with Univers display by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. There is a damaging and self-defeating assumption that theory is necessarily the elite language of the socially and culturally privileged. It is said that the place of the academic critic is inevitably within the Eurocentric archives of an imperialist or neo-colonial West. —HOMI K. BHABHA, The Location of Culture Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: A pigs Eye View of Europe 1 1 The Discovery of Europe: Some Critical Points 11 2 Montesquieu’s North and South: History as a Theory of Europe 52 3 Republics of Letters: What Is European Literature? 87 4 Mme de Staël to Hegel: The End of French Europe 134 5 Orientalism, Mediterranean Style: The Limits of History at the Margins of Europe 172 Notes 219 Works Cited 239 Index 267 Acknowledgments I want to thank for their suggestions, time, and support all the people who have heard, read, and commented on parts of this book: Albert Ascoli, David Bell, Joe Buttigieg, miriam cooke, Sergio Ferrarese, Ro- berto Ferrera, Mia Fuller, Edna Goldstaub, Margaret Greer, Michele Longino, Walter Mignolo, Marc Scachter, Helen Solterer, Barbara Spack- man, Philip Stewart, Carlotta Surini, Eric Zakim, and Robert Zimmer- man. Also invaluable has been the help o√ered by the Ethical Cosmopol- itanism group and the Franklin Humanities Seminar at Duke University; by the Program in Comparative Literature at Notre Dame; by the Khan Institute Colloquium at Smith College; by the Mediterranean Studies groups of both Duke and New York University; and by European studies and the Italian studies program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. -

Islam & Sufism

“There is no Deity except Allah; Mohammad (SM) (PBUH) is The Messenger of Allah” IN THE NAME OF ALLAH, MOST GRACIOUS & MOST MERCIFUL “The Almighty God Certainly HAS BEEN, IS and WILL CONTINUE to Send Infinite Love and Affection to His Beloved Prophet Hazrat Mohammad (SM) (PBUH) along with his Special Angels who are Directed by the Almighty God to Continuously Salute with Respect, Dignity and Honor to the Beloved Holy Prophet for His Kind Attention. The Almighty God again Commanding to the True Believers to Pay Respect with Dignity and Honor for Their Forgiveness and Mercy from the Beloved Holy Prophet of Islam and Mankind.” - (Al‐Quran Surah Al-Ahzab, 33:56) “Those who dies in the Path of Almighty God, Nobody shall have the doubt to think that they are dead but in fact they are NOT dead but Alive and very Close to Almighty, Even Their every needs even food are being sent by Almighty, but people among you will not understand.” - (Al‐Quran Surah Al-Imran 3:169) “Be Careful of the Friends of Almighty God, They do not worry about anything or anybody.” - (Al‐Quran, Surah Yunus 10:62) “Those who dies or pass away in the Path of Almighty God, nobody shall think about Them as They are dead, But people can not understand Them.” - (Al‐Quran, Surah Baqarah 2:154) Author: His Eminency Dr. Hazrat Sheikh Shah Sufi M N Alam (MA) 2 His Eminency Dr. Hazrat Sheikh Shah Sufi M N Alam’s Millennium Prophecy Statement Authentic History of The World Arrival of Imam Mahdi (PBUH) with Reemergence of Jesus Christ (A) To Co-Create Heaven on Earth Published by: Millennium Trade Link USA Corporation Library of Congress, Cataloging in Publication Data Copyright@ 2019 by His Eminency Dr. -

Mike Vax Live! Mp3, Flac, Wma

Mike Vax Mike Vax Live! mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Mike Vax Live! Country: US Released: 1976 Style: Big Band MP3 version RAR size: 1341 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1220 mb WMA version RAR size: 1850 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 123 Other Formats: AU ASF MPC APE FLAC MOD AAC Tracklist Hide Credits Buffalo Breath A1 Soloist, Tenor Saxophone – Brian GarrardSoloist, Trumpet – Mike VaxWritten-By – Bob 4:25 Secor Consolation Soloist, Baritone Saxophone – Terry StanfilSoloist, Flute – Glen RichardsenSoloist, Tenor A2 6:55 Saxophone – Gerry GilmoreSoloist, Trombone – Dean HubbardSoloist, Trumpet – Brian Atkinson, Mike VaxWritten-By – Terry Stanfil Ptah Soloist, Alto Saxophone – Kim FrizellSoloist, Drums – Jim ThorneSoloist, Piano – Si A3 6:10 PerkoffSoloist, Tenor Saxophone – Gerry GilmoreSoloist, Trumpet – Brian Atkinson, Mike VaxWritten-By – Warren Gale Zeek's Blues A4 Soloist, Tenor Saxophone – Gerry GilmoreSoloist, Trombone – Dean HubbardSoloist, 3:50 Trumpet – Mike VaxWritten-By – Bob Secor El Zapalote B1 5:45 Soloist, Trumpet – Mike VaxWritten-By – Matt Schoen Pablo's Dream B2 4:15 Soloist, Alto Saxophone – Kim FrizellSoloist, Trumpet – Mike VaxWritten-By – Matt Schoen Escapade B3 5:35 Arranged By – Rich WilkinsSoloist, Piano – Si PerkoffWritten-By – Norm Tufts Bunch Of Blues B4 Soloist, Piano – Si PerkoffSoloist, Tenor Saxophone – Brian GarrardSoloist, Trombone – 4:56 Dean HubbardSoloist, Trumpet – Brain Atkinson, Mike VaxWritten-By – Les Hooper Companies, etc. Distributed By – IS Music Lacquer Cut At – Masterfonics Pressed By – GRT Record Pressing Recorded At – Cazadero Music Camp Recorded By – Location Recording Service Credits Bass – Jeremy Choen Brass – Bill Main, Dave Candia, Jim Schlicht Concept By [Cover] – Peggy Vax Cover, Artwork – Virginia Vax Drums – Jim Thorne Flute – Glen Richardsen Graphics – Dale Milford Leader, Trumpet, Liner Notes – Mike Vax Photography By [Back Cover] – Sydney Vax Piano – Si Perkoff Producer – Gary Edwards Producer, Mixed By [Final Mixdown] – Gary J. -

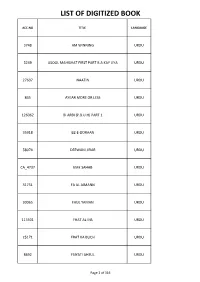

List of Digitized Book

LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK ACC.NO TITLE LANGUAGE 3748 AM WINNING URDU 5249 ASOOL MAHISHAT FIRST PART B.A KAY LIYA URDU 27607 NAATIN URDU 845 AYEAR MORE OR LESS URDU 126062 BI ARBI (P.B.U.H) PART 1 URDU 35918 BZ-E-DORAAN URDU 58074 DEEWANI JIRAR URDU CA_4737 EME SAHAB URDU 31751 FA AL AIMANN URDU 30065 FAUL YAMAN URDU 113501 FHAT AL INS URDU 25171 FRAT KA BUCH URDU 8692 FSIYATI AHSUL URDU Page 1 of 316 LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK 30138 FSIYAT-I-AFFA URDU 34069 FTAHUL YAMAN URDU 1907 FTAHUL YAMAN BATASHYAT URDU 24124 GAMA-I-TIBISHAZAD URDU 58190 GAMAT UL ASRAR URDU 3509 GD SAKHN URDU 64958 GMA SARMAD URDU 114806 GMAH JAVEED URDU 30328 GMAY ZAR URDU 180689 GSH FIRQAADI URDU 126188 HBZ HAYAT URDU 23817 I AUR PURANI TALEEM URDU 38514 IR G KHAYAL URDU 63302 JANGI AZADI ATHARA SO SATAWAN URDU Page 2 of 316 LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK 27796 KASH WA KASH URDU 24338 L DAMNIYATI URDU 57853 LAH TASLEEM URDU 5328 MEYATI KEMEYA KI DARSI KITAB URDU 36585 MOD-E-ZINDAGI URDU 113646 MU GAZAL FARSI URDU 1983 PAD MA SHEIKH FARIDIN ATTAR URDU ASL101 PARISIAN GRAMMER URDU 109279 QASH-I-AKHIR URDU 36043 QOOSH MAANI URDU 7085 QOOSHA RANGA RANG URDU 59166 QSH JAWOODAH URDU 38510 QSH WA NIGAAR URDU 23839 RA ZIKIR HUSSAIN(AS) URDU Page 3 of 316 LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK 456791 SAB ZELI RIYAZI URDU 5374 SEEBIYAT URDU 55986 SHRIYATI MAJID FIRST PART URDU 56652 SIRUL SHQEEN WA GAZLIYAT WA QASAYID URDU 47249 TAIEJ ALZAHAN WAFIZAN AL FIKAR URDU 11195 TAK KHATHA URDU ASL124 TIYA KALAM URDU 109468 VEEN BHARAT URDU CA_4731 WA-E-SHAIDA URDU ASL_286 YA HISAAB URDU 39350 ZAM HIYA HIYA URDU -

Concert: Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra & Lew Tabackin

Ithaca College Digital Commons IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 9-15-1996 Concert: Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra & Lew Tabackin Toshiko Akiyoshi Lew Tabackin Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Akiyoshi, Toshiko; Tabackin, Lew; and Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra, "Concert: Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra & Lew Tabackin" (1996). All Concert & Recital Programs. 7545. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/7545 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons IC. ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERTS 1996-97 TOSHIKO AKIYOSHI JAZZ ORCHESTRA FEATURING LEW TABACKIN TOSHIKO AKIYOSHI, conductor, composer, arranger LEW TABACKIN, tenor saxophone and flute 13aru2 Toshiko Akiyoshi 1.tm Doug Weiss* Drums Terry Clarke ~ Dave Pietro* Lew Tabackin Jim Snidero Walt Weiskopf Scott Robinson Trumpet Mike Ponella* John Eckert Scott Wendhodt Joe Magnelli Trombone Scott Whitfield* Steve Amour Luis Bonilla Tim Newman Percussion Valtinho Road Manager George Whitington Ford Hall Auditorium Sunday, September 15, 1996 8:15 p.m. • section leader Management: The Berkeley Agency, 2608 Ninth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 TOSHIKO AKIYOSHI Toshiko Akiyoshi was born in Manchuria, China, and was considering a career in medicine when her family returned to live in Japan. She already had some training as a classical pianist, when she got a job playing in a dance hall in Beppu. Her family wasn't thrilled with the idea, but they finally agreed that she could play until the school year began. -

Breakthroughs

- 516-248-9600 " Number 53 Volume 11 No. 7 Published biweekly November 12,1984 by CMI Media 388 Repoders 834 Willis Ave., Albertson, NY 11507 FRANKIE GOES TO HOLLYWOOD BIG COUNTRY REDUCERS ..... • Welcome To The Steeltown Let's Go! Pleasuredome Mercury-PG Rave-On Island N/1/11/11 RADIO CLUBS RETAIL 1. U2 DAVID BOWIE U2 2. General Publ c Frankie/Hollywocd Prince 3. Let's Active Prince David Bowie Breakthroughs RADIO CLUBS RETAIL 1. REPLACEMENTS CULTURE CLUB HONEYDRIPPERS 2. Orch. Manoeuvres Hall/Oates General Public 3. XTC Maria Vidal XTC New Music (noo myoo-mic), n. 1. fresh, modern, novel, different, striking, [ better, the latest, anew. 2 the best rock, jazz, reggae, soul, dance music— from the world's noet innovative and dynamic musicians. CMJ New Music Report, November 12, 1984 RADIO CLUBS RETAIL 1. REPLACEMENTS 1. CULTURE CLUB 1. HONEYDRIPPERS 2. Orchestral Manoeuvres 2. Daryl Hall/John Oates 2. General Public 3. XTC 3. Maria Vidal 3. XTC 4. UB40 4. Sheena Easton 4. Replacements 5. Devo 5. Bronski Beat 5. Barbra Streisand 6. Honeydrippers 6. Bruce Springsteen 6. Chaka Khan 7. Get Smart 7. General Public 7. Style Council 8. Ministry 8. INXS 8. Devo 9. Nails 9. Paul McCartney 9. Daryl Hall/John Oates 10. Captain Sensible 10. Apollonia 6 10. Lou Reed RADIO CLUBS RETAIL 14 -ve 1,44arietia4k2 fire 1. U2 1. DAVID BOWIE 1. U2 2. General Public 2. Frankie Goes To Hollywood 2. Prince 3. Let's Active 3. Prince 3. David Bowie 4. Aztec Camera 4. Romeo Void 4. Bruce Springsteen 5. -

1. INTRODUCTION the Significance of Environmental Justice Movement

A QUEST FOR ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE IN JEANETTE WINTERSON’S THE STONE GODS Najmeh NOURI* ABSTRACT The environmental justice approach is most explicitly associated with minority communities that are characterized as the most vulnerable individuals in environmentally driven challenges. Jeanette Winterson’s The Stone Gods (2007) is an exemplary novel which creates a form of critique that targets issues like gender, class, and race and parallels them with ecological concerns. In this perspective, The Stone Gods criticizes the exclusionary systems that produce center and margin oppositions in both human and nonhuman worlds. Furthermore, the novel provides a background for discussion of people and places that are linked to the ecological issues in urban environments including downtown and outskirt areas. Using environmental justice approach as a main framework of analysis, this paper aims to investigate how Winterson utilizes ecological collapse as a productive tool to trouble normative power structures, embedded social binaries, and inequality in society. In doing so, the study will scrutinize the place of power and its underlying discourses that lead to the construction of inferiority and otherness and accordingly will examine their primary role in environmental degradation. 1 Keywords: Jeanette Winterson, The Stone Gods, Environmental Justice, Gender, Class, Race 1. INTRODUCTION The significance of environmental justice movement lies in the fact that it attempts to explore the ways in which “environmental problems do not affect us equally and that specific environmental concerns are not universal” (Gardner, 1999:204). Within this perspective, environmental justice, on the one hand, scrutinizes the interaction of minority groups with natural environment and on the other hand, it focuses on the inequalities that emerges as a result of marginalization in urban and industrial areas.