Tour Guide Manual)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

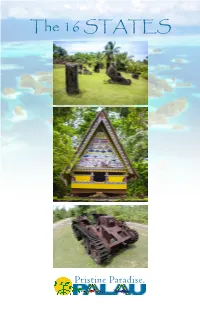

The 16 STATES

The 16 STATES Pristine Paradise. 2 Palau is an archipelago of diverse terrain, flora and fauna. There is the largest island of volcanic origin, called Babeldaob, the outer atoll and limestone islands, the Southern Lagoon and islands of Koror, and the southwest islands, which are located about 250 miles southwest of Palau. These regions are divided into sixteen states, each with their own distinct features and attractions. Transportation to these states is mainly by road, boat, or small aircraft. Koror is a group of islands connected by bridges and causeways, and is joined to Babeldaob Island by the Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge. Once in Babeldaob, driving the circumference of the island on the highway can be done in a half day or full day, depending on the number of stops you would like. The outer islands of Angaur and Peleliu are at the southern region of the archipelago, and are accessable by small aircraft or boat, and there is a regularly scheduled state ferry that stops at both islands. Kayangel, to the north of Babeldaob, can also be visited by boat or helicopter. The Southwest Islands, due to their remote location, are only accessible by large ocean-going vessels, but are a glimpse into Palau’s simplicity and beauty. When visiting these pristine areas, it is necessary to contact the State Offices in order to be introduced to these cultural treasures through a knowledgeable guide. While some fees may apply, your contribution will be used for the preservation of these sites. Please see page 19 for a list of the state offices. -

The Palau Community Association of Guam, 1948 to 1997

MICRONESIAN JOURNAL OF THE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Vol. 5, nº 1 Dry Season Issue June 2006 FROM SOUL TO SOMNOLENCE: THE PALAU COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION OF GUAM, 1948 TO 1997 Francesca K. Remengesau Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, Government of Guam Dirk Anthony Ballendorf Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam This article provides a narrative reflective history of the founding, growth, development, decline, and near end of the Palau Community Association of Guam. The historical experience of this community association parallels, in some re- spects, the growth and development also of Guam. It examines the early immigration of Palauans to Guam; their moti- vations, their success, and their thoughts on the future. A wide diversity of Palauan opinion has been gathered for this study beginning with testimonies from early immigrants following World War Two, to young people who are students and workers. The Palau Community Association of Guam This study provides information on the his- (PCA) has been a very important social and torical as well as the contemporary experience cultural institution for Palauans on Guam for of the members of the Palauan community on more than fifty years. A comprehensive history Guam, and also describes the Palauan skill at of the development, activities, and social evolu- socio-cultural change in the context of migra- tion of this association has never been re- tion and transition to a wage economy, and corded before now. It is important for the considers the impact of a new socio-cultural present Palauan community of Guam, espe- setting on women’s economic roles, on tradi- cially the younger people, to know about the tional customs, and on education. -

CGGJ Vansteenis

BIBLIOGRAPHY : ALGAE 3957 X. Bibliography C.G.G.J. van Steenis (continued from page 3864) The entries have been split into five categories: a) Algae — b) Fungi & Lichens — c) Bryophytes — d) Pteridophytes — e) Spermatophytes 8 General subjects. — Books have been marked with an asterisk. a) Algae: ABDUS M & Ulva a SALAM, A. Y.S.A.KHAN, patengansis, new species from Bang- ladesh. Phykos 19 (1980) 129-131, 4 fig. ADEY ,w. H., R.A.TOWNSEND & w„T„ BOYKINS, The crustose coralline algae (Rho- dophyta: Corallinaceae) of the Hawaiian Islands. Smithson„Contr„ Marine Sci. no 15 (1982) 1-74, 47 fig. 10 new) 29 new); to subfamilies and genera (1 and spp. (several key genera; keys to species„ BANDO,T„, S.WATANABE & T„NAKANO, Desmids from soil of paddyfields collect- ed in Java and Sumatra. Tukar-Menukar 1 (1982) 7-23, 4 fig. 85 species listed and annotated; no novelties. *CHRISTIANSON,I.G., M.N.CLAYTON & B.M.ALLENDER (eds.), B.FUHRER (photogr.), Seaweeds of Australia. A.H.& A.W.Reed Pty Ltd., Sydney (1981) 112 pp., 186 col.pl. Magnificent atlas; text only with the phyla; ample captions; some seagrasses included. CORDERO Jr,P.A„ Studies on Philippine marine red algae. Nat.Mus.Philip., Manila (1981) 258 pp., 28 pi., 1 map, 265 fig. Thesis (Kyoto); keys and descriptions of 259 spp„, half of them new to the Philippines; 1 new species. A preliminary study of the ethnobotany of Philippine edible sea- weeds, especially from Ilocos Norte and Cagayan Provinces. Acta Manillana A 21 (31) (1982) 54-79. Chemical analysis; scientific and local names; indication of uses and storage. -

Newsletter No

Newsletter No. 167 June 2016 Price: $5.00 AUSTRALASIAN SYSTEMATIC BOTANY SOCIETY INCORPORATED Council President Vice President Darren Crayn Daniel Murphy Australian Tropical Herbarium (ATH) Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria James Cook University, Cairns Campus Birdwood Avenue PO Box 6811, Cairns Qld 4870 Melbourne, Vic. 3004 Australia Australia Tel: (+61)/(0)7 4232 1859 Tel: (+61)/(0) 3 9252 2377 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Secretary Treasurer Leon Perrie John Clarkson Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service PO Box 467, Wellington 6011 PO Box 975, Atherton Qld 4883 New Zealand Australia Tel: (+64)/(0) 4 381 7261 Tel: (+61)/(0) 7 4091 8170 Email: [email protected] Mobile: (+61)/(0) 437 732 487 Councillor Email: [email protected] Jennifer Tate Councillor Institute of Fundamental Sciences Mike Bayly Massey University School of Botany Private Bag 11222, Palmerston North 4442 University of Melbourne, Vic. 3010 New Zealand Australia Tel: (+64)/(0) 6 356- 099 ext. 84718 Tel: (+61)/(0) 3 8344 5055 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Other constitutional bodies Hansjörg Eichler Research Committee Affiliate Society David Glenny Papua New Guinea Botanical Society Sarah Matthews Heidi Meudt Advisory Standing Committees Joanne Birch Financial Katharina Schulte Patrick Brownsey Murray Henwood David Cantrill Chair: Dan Murphy, Vice President Bob Hill Grant application closing dates Ad hoc adviser to Committee: Bruce Evans Hansjörg Eichler Research -

A Summary of Palau's Typhoon History 1945-2013

A Summary of Palau’s Typhoon History 1945-2013 Coral Reef Research Foundation, Palau Dec, 2014 © Coral Reef Research Foundation 2014 Suggested citation: Coral Reef Research Foundation, 2014. A Summary of Palau’s Typhoon History. Technical Report, 17pp. www.coralreefpalau.org Additions and suggestions welcome. Please email: [email protected] 2 Summary: Since 1945 Palau has had 68 recorded typhoons, tropical storms or tropical depressions come within 200 nmi of its islands or reefs. At their nearest point to Palau, 20 of these were typhoon strength with winds ≥64kts, or an average of 1 typhoon every 3 years. November and December had the highest number of significant storms; July had none over 40 kts and August had no recorded storms. Data Compilation: Storms within 200 nmi (nautical miles) of Palau were identified from the Digital Typhoon, National Institute of Informatics, Japan web site (http://agora.ex.nii.ac.jp/digital- typhoon/reference/besttrack.html.en). The storm tracks and intensities were then obtained from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) (https://metoc.ndbc.noaa.gov/en/JTWC/). Three storm categories were used following the JTWC: Tropical Depression, winds ≤ 33 kts; Tropical Storm, winds 34-63 kts; Typhoon ≥64kts. All track data was from the JTWC archives. Tracks were plotted on Google Earth and the nearest distance to land or reef, and bearing from Palau, were measured; maximum sustained wind speed in knots (nautical miles/hr) at that point was recorded. Typhoon names were taken from the Digital Typhoon site, but typhoon numbers for the same typhoon were from the JTWC archives. -

Hunter-Anderson 2000

Micronesica 33(1/2) 12/10/00 2:01 PM Page 11 Micronesica 33(1/2):11-44, 2000 Ethnographic and Archaeological Investigations in the Southwest Islands of Palau ROSALIND L. HUNTER-ANDERSON Micronesian Archaeological Research Services P.O. Box 22303 GMF, Guam 96921 U.S.A. Abstract—Ethnographic and archaeological field work was conducted in 1992 at Tobi, Merir, Pulo Anna, Sonsorol, and Fana. At Tobi, docu- mentation included profiling a wave-cut exposure of a ritual area mound near the landing on the western side of the island and retrieving a soil sample from the base of the mound for radiocarbon dating; locating and describing seventeen earth-oven refuse mounds and excavating a shovel trench into one of them, from which a charcoal sample was retrieved for radiocarbon dating; photographing artifacts observed on the ground sur- face and in private collections; recording information on traditional resource use at Tobi and nearby Helen Reef; and interviewing older Tobians living in Koror regarding traditional practices. A paleosediment core was taken at an inland taro patch. At Merir, the surface features on the large residential mound near the landing on the west side of the island were sketched in plan and information recorded about the mound’s former uses; a shovel trench was excavated into the south flank of the mound, and a paleosediment core was taken at a small taro patch inland of the mound. Artifacts from the surface at the beach were photographed. At Pulo Anna, a shovel trench was excavated into a residential mound and charcoal samples col- lected for radiocarbon dating and a paleosediment core was taken at the margin of the large inland salt water pond. -

Republic of Palau

REPUBLIC OF PALAU Palau Public Library Five-Year State Plan 2020-2022 For submission to the Institute of Museum and Library Services Submitted by: Palau Public Library Ministry of Education Republic of Palau 96940 April 22, 2019 Palau Five-Year Plan 1 2020-2022 MISSION The Palau Public Library is to serve as a gateway for lifelong learning and easy access to a wide range of information resources and to ensure the residents of Palau will be successful, literate and resourceful in the Palauan society and the world. PALAU PUBLIC LIBRARY BACKGROUND The Palau Public Library (PPL), was established in 1964, comes under the Ministry of Education. It is the only public library in the Republic of Palau, with collections totaling more than 20,000. The library has three full-time staff, the Librarian, the Library Assistant, and the Library Aide/Bookmobile Operator. The mission of the PPL is to serve as a gateway to lifelong learning and easy access to a wide range of information resources to ensure the residents of Palau will be successful, literate, and resourceful in the Palauan society and world. The PPL strives to provide access to materials, information resources, and services for community residents of all ages for professional and personal development, enjoyment, and educational needs. In addition, the library provides access to EBSCOHost databases and links to open access sources of scholarly information. It seeks to promote easy access to a wide range of resources and information and to create activities and programs for all residents of Palau. The PPL serves as the library for Palau High School, the only public high school in the Republic of Palau. -

Global ENVIRONMENT FACILITY INVESTING in OUR PLANET

GLOBAl ENVIRONMENT FACILITY INVESTING IN OUR PLANET Naoko Ishii CEO and Chairperson August 22, 2016 Dear Council Member, The F AO as the Implementing Agency for the project entitled: Vanuatu: R2R: Integrated Sustainable Land and Coastal Management under the Regional: R2R- Pacific Islands Ridge-to• Reef National Priorities d€" Integrated Water, Land, Forest and Coastal Management to Preserve Biodiversity, Ecosystem Services, Store Carbon, Improve Climate Resilience and Sustain Livelihoods, has submitted the attached proposed project document for CEO endorsement prior to final Agency approval of the project document in accordance with the FAO procedures. The Secretariat has reviewed the project document. It is consistent with the project concept approved by the Council in November 2013 and the proposed project remains consistent with the Instrument and OEF policies and procedures. The attached explanation prepared by the F AO satisfactorily details how Council's comments and those of the STAP have been addressed. We have today posted the proposed project document on the OEF website at www.TheOEF.org for your information. We would welcome any comments you may wish to provide by September 20,2016 before I endorse the project. You may send your comments to [email protected] . If you do not have access to the Web, you may request the local field office ofUNDP or the World Bank to download the document for you. Alternatively, you may request a copy of the document from the Secretariat. If you make such a request, please confirm for us -

2006 Statistical Yearbook

2006 Statistical Yearbook Division of Research & Evaluation P.O. Box 7080 Koror, Palau 96940 Published April 2006 Acknowledgements This publication was made possible through the support of many people within the education sector. A special acknowledgement goes to the school principals for actively participating in the Annual School Survey conducted, the Division of Personnel Management and Administrative Services Section for assistance in collection of other data within the ministry. Finally, the staffs of the Division of Research and Evaluation are commended for compilation of this publication. Introduction The Education Statistical Yearbook 2006 is an annual publication of the Ministry of Education. It provides a range of statistical information about education in the Republic of Palau and serves as a reference for school officials and others responsible for planning and implementing activities concerning education and the development of our youth. The statistical information contained in this publication is comprised of data collected with the Annual School Survey conducted in July 2006 and data from other sources within the Ministry of Education. This publication’s layout begins with a summary of all the schools in the Republic of Palau. The following shows how the publication is organized. School Information Students’ Information Personnel Information Facilities & Equipments Finance Definition of Terms Acronyms Terms Definition BMS Belau Modekngei School Dropout This refers to any student who leaves school for a period of 15 consecutive school days without request of a transcript or withdrawal request from parents. Students who drop out of school do not return to school within the same school year that they left school. -

Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau

THREA TENED ENDEMIC PLANTS OF PALAU BIODI VERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 19 BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 19 Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series is published by: Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) and Conservation International Pacific Islands Program (CI-Pacific) PO Box 2035, Apia, Samoa T: + 685 21593 E: [email protected] W: www.conservation.org The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation. Conservation International Pacific Islands Program. 2013. Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series 19: Threatened Endemic Plants of Palau. Conservation International, Apia, Samoa Authors: Craig Costion, James Cook University, Australia Design/Production: Joanne Aitken, The Little Design Company, www.thelittledesigncompany.com Photo credits: Craig Costion (unless cited otherwise) Cover photograph: Parkia flowers. © Craig Costion Series Editors: Leilani Duffy, Conservation International Pacific Islands Program Conservation International is a private, non-profit organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. OUR MISSION Building upon a strong foundation of science, partnership and field demonstration, -

Micrdnlms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

US Ships in Commission, Under Construction, and in Mothballs 1 September 1939

US Ships in Commission, Under Construction, and in Mothballs 1 September 1939 Ships in commission (Total 339 ships) Battleships USS Arizona (BB-39) USS Arkansas (BB-33) USS California (BB-44) USS Colorado (BB-45) USS Idaho (BB-42) USS Maryland (BB-46) USS Mississippi (BB-41) USS Nevada (BB-36) USS New Mexico (BB-40, ex-California) USS New York (BB-34) USS Oklahoma (BB-37) USS Pennsylvania (BB-38) USS Tennessee (BB-43) USS Texas (BB-35) USS West Virginia (BB-48) Aircraft Carriers USS Enterprise (CV-6) USS Lexington (CV-2, ex CC-1, ex Constitution) USS Ranger (CV-4) USS Saratoga (CV-3, ex CC-3) USS Yorktown (CV-5) Heavy Cruisers USS Astoria (CA-34, ex CL-34) USS Augusta (CA-31, ex CL-31) USS Chester (CA-27, ex CL-27) USS Chicago (CA-29, ex CL-29) USS Houston (CA-30, ex CL-30) USS Indianapolis) (CA-35, ex CL-35) USS Lousiville (CA-28, ex CL-28) USS Minneapolis (CA-36, ex CL-36) USS New Orleans (CA-32, ex CL-32) USS Northampton (CA-26, ex CL-26) USS Pensacola (CA-24, ex CL-24) USS Portland (CA-33, ex CL-33) USS Quincy (CA-39, ex CL-39) USS Salt Lake City (CA-25, ex CL-25) USS San Francisco (CA-38, ex CL-38) USS Tuscaloosa (CA-37, ex CL-37) USS Vincennes (CA-44, CL-44) USS Wichita (CA-45) Light Cruisers USS Boise (CL-47) USS Brooklyn (CL-40) USS Cincinnati (CL-6, ex CS-6) USS Concord (CL-10, ex CS-10) USS Detroit (CL-8, ex CS-8) USS Honolulu (CL-48) USS Marblehead (CL-12, ex CS-12) 1 USS Memphis (CL-13, ex CS-13) USS Milwaukee (CL-5, ex CS-5) USS Nashville (CL-43) USS Omaha (CL-4, ex CS-4) USS Philadelphia (CL-41) USS Phoenix (CL-46) USS Raleigh (CL-7, ex CS-7) USS Richmond (CL-9, ex CS-9) USS St.