Hunter-Anderson 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

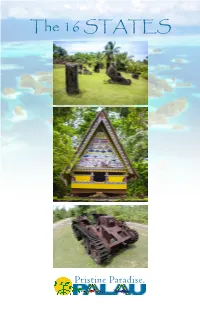

The 16 STATES

The 16 STATES Pristine Paradise. 2 Palau is an archipelago of diverse terrain, flora and fauna. There is the largest island of volcanic origin, called Babeldaob, the outer atoll and limestone islands, the Southern Lagoon and islands of Koror, and the southwest islands, which are located about 250 miles southwest of Palau. These regions are divided into sixteen states, each with their own distinct features and attractions. Transportation to these states is mainly by road, boat, or small aircraft. Koror is a group of islands connected by bridges and causeways, and is joined to Babeldaob Island by the Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge. Once in Babeldaob, driving the circumference of the island on the highway can be done in a half day or full day, depending on the number of stops you would like. The outer islands of Angaur and Peleliu are at the southern region of the archipelago, and are accessable by small aircraft or boat, and there is a regularly scheduled state ferry that stops at both islands. Kayangel, to the north of Babeldaob, can also be visited by boat or helicopter. The Southwest Islands, due to their remote location, are only accessible by large ocean-going vessels, but are a glimpse into Palau’s simplicity and beauty. When visiting these pristine areas, it is necessary to contact the State Offices in order to be introduced to these cultural treasures through a knowledgeable guide. While some fees may apply, your contribution will be used for the preservation of these sites. Please see page 19 for a list of the state offices. -

A Summary of Palau's Typhoon History 1945-2013

A Summary of Palau’s Typhoon History 1945-2013 Coral Reef Research Foundation, Palau Dec, 2014 © Coral Reef Research Foundation 2014 Suggested citation: Coral Reef Research Foundation, 2014. A Summary of Palau’s Typhoon History. Technical Report, 17pp. www.coralreefpalau.org Additions and suggestions welcome. Please email: [email protected] 2 Summary: Since 1945 Palau has had 68 recorded typhoons, tropical storms or tropical depressions come within 200 nmi of its islands or reefs. At their nearest point to Palau, 20 of these were typhoon strength with winds ≥64kts, or an average of 1 typhoon every 3 years. November and December had the highest number of significant storms; July had none over 40 kts and August had no recorded storms. Data Compilation: Storms within 200 nmi (nautical miles) of Palau were identified from the Digital Typhoon, National Institute of Informatics, Japan web site (http://agora.ex.nii.ac.jp/digital- typhoon/reference/besttrack.html.en). The storm tracks and intensities were then obtained from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) (https://metoc.ndbc.noaa.gov/en/JTWC/). Three storm categories were used following the JTWC: Tropical Depression, winds ≤ 33 kts; Tropical Storm, winds 34-63 kts; Typhoon ≥64kts. All track data was from the JTWC archives. Tracks were plotted on Google Earth and the nearest distance to land or reef, and bearing from Palau, were measured; maximum sustained wind speed in knots (nautical miles/hr) at that point was recorded. Typhoon names were taken from the Digital Typhoon site, but typhoon numbers for the same typhoon were from the JTWC archives. -

Helen Reef 2008: an Overview

Helen Reef 2008: an Overview by Patrick L. Colin, Lori J. Bell and Sharon Patris Coral Reef Research Foundation P.O. Box 1765 Koror, Palau 96940 [email protected] Technical Report 2008 © Coral Reef Research Foundation Suggested citation: Colin, P.L., L.J. Bell and S. Patris. 2008. Helen Reef 2008: An Overview. Technical Report, Coral Reef Research Foundation, 31pp. www.coralreefpalau.org CORAL REEF RESEARCH FOUNDATION Report to Helen Reef Project SW Islands Collecting Trip, Sept 2008 INTRODUCTION In September 2008 the Coral Reef Research Foundation (CRRF) participated in a 3 week trip to Sonsorol and Hatohobei States for the purpose of marine invertebrate collections for the US National Cancer Institute (NCI). In addition to the NCI collections we were able to make a considerable number of general observations about marine conditions as well as gather a variety of data on tides, currents and temperatures at Helen Reef. The trip was a shared charter aboard the live-aboard dive boat Pacific Explorer II, in conjunction with fish biologists Rick Winterbottom (Royal Ontario Museum, Canada) and Mark Westneat (Field Museum, Chicago), from 10 – 29 September 2008. This report is intended to summarize the observations and collections made by CRRF. Two previous small collections were made in the Southwest Islands by CRRF, July 1995 to Sonsorol State, and December 1996 to Hatohobei State. Some of those results are summarized here for continuity in data. The Southwest Islands of Palau represent an area which is intermediate between the ultra diverse "Coral Triangle" (Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Malaysia, Solomon Islands, Philippines) and the less (but still very high) diverse Micronesian islands. -

Addressing Water Sector Climate Change Vulnerabilities in the Outlying Island States of Palau

A NATIONAL CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION PROJECT Global Climate Change Alliance Addressing water sector climate change vulnerabilities in the outlying island states of Palau Focusing on the specific water issues experienced by residents in remote island communities – climate change adaptation in Palau. Project amount How does this project assist climate remote island communities. There has been a change adaptation? need for flexibility as the project progresses. € 0.5 million (approx. USD 0.66 million) funded by For example, Typhoon Haiyan in 2013 affected the European Union Water security has been identified as a key Kyangel, Palau’s northernmost island state, challenge for Palau. This is a conclusion drawn creating the need to reassess and redesign Project period from vulnerability and adaptation assessments local project implementation. conducted in-country by both government and 31 July 2013 to 30 June 2015 • The Palau Public Utilities Corporation non-governmental organisations. The problem infrastructure has been significantly is considered particularly acute among the more enhanced. For example, a backup generator Implementing agencies remote outlying islands. and carbon filters and aerators have been Office of Environmental Response and added to the Angaur water system, as well Coordination; Palau Public Utilities Corporation Climate change is exacerbating problems in the as improvements to household and communal Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) water sector because (i) air temperatures are water systems in other islands. projected to continue rising, affecting evaporation • Innovative partnerships have addressed the Partners rates and the availability of good quality water; challenges faced in implementing project (ii) changes in precipitation and extreme weather activities in extremely remote communities. -

“There Is No Place Like Home”

stephanie walda-mandel “There is no place Migration and Cultural Identity like home” of the Sonsorolese, Micronesia HEIDELBERG STUDIES IN PACIFIC ANTHROPOLOGY 5 heidelberg studies in pacific anthropology Volume 5 Edited by jürg wassmann stephanie walda-mandel “T here is no place like home” Migration and Cultural Identity of the Sonsorolese, Micronesia Universitätsverlag winter Heidelberg Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Diese Veröffentlichung wurde als Dissertation im Jahr 2014 unter dem Titel “There’s No Place Like Home”: Auswirkungen von Migration auf die kulturelle Identität von Sonsorolesen im Fach Ethnologie an der Fakultät für Verhaltens- und Empirische Kulturwissenschaften der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg angenommen. cover: Father and son on the way to Sonsorol © S. Walda-Mandel 2004 isbn 978-3-8253-6692-6 Dieses Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages unzulässig und strafbar. Das gilt ins- besondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Systemen. © 2016 Universitätsverlag Winter GmbH Heidelberg Imprimé en Allemagne · Printed in Germany Umschlaggestaltung: Klaus Brecht GmbH, Heidelberg Druck: Memminger MedienCentrum, -

Tour Guide Manual)

KOROR STATE GOVERNMENT Tour Guide Training and Certification Program Contents Acknowledgments .......................................................................................... 4 Palau Today .................................................................................................... 5 Message from the Koror State Governor ...........................................................6 UNESCO World Heritage Site .............................................................................7 Geography of Palau ...........................................................................................9 Modern Palau ..................................................................................................15 Tourism Network and Activities .......................................................................19 The Tour Guide ............................................................................................. 27 Tour Guide Roles & Responsibilities ................................................................28 Diving Briefings ...............................................................................................29 Responsible Diving Etiquette ...........................................................................30 Coral-Friendly Snorkeling Guidelines ...............................................................30 Best Practice Guidelines for Natural Sites ........................................................33 Communication and Public Speaking ..............................................................34 -

Linguistic Sketch of Hatohobeian and Sonsorolese: a Study of Phonology and Morphology

Linguistic Sketch of Hatohobeian and Sonsorolese: a study of phonology and morphology Date: 3 February 2014 Author: Esther van den Berg Supervisors: Dr. Prof. L. de Vries, VU University Dr. J. Ellis, Summer Institute of Linguistics 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction 3 2 Literature on the South-West Islands 6 3 Data collection 10 4 Phonology 13 4.1.the CV-pattern 13 4.2 Phonemics 14 4.2.1 Vowels 4.2.2 Consonants 5 Morphophonology 23 5.1 The noun phrase 24 5.2 The verb phrase 33 6 Orthography 44 7 Discussion 46 8 Conclusion 47 Bibliography 49 2 1 Introduction The South-West Islands are a group of small, remote islands to the South-West of the Republic of Palau, represented in the Palauan government as Sonsorol State, which includes the islands of Sonsorol (Dongosaro), Fanna, Merir and Pulo Anna, and Hatohobei State, formerly Tobi State, which includes Hatohobei and the for al intents and purposes uninhabited Helen Island. In some sense, they are outer islands of Palau, dependend upon the Republic politically and economically. But culturally and linguistically, they have very little in common with the rest of the Palauan archipelago. What separates them from Palau is first and foremost the great blue ocean: the island group of Sonsorol, Fanna, Merir and Pula Anna is located approximately 300 km away from Koror, Palau, and Hatohobei is at a distance of 484.1 kilometers. But equally important is that the Hatohobeians and Sonsorolese have a distinct cultural identity and linguistic heritage, closely related to that of the Carolinian islands, which include Woleaian, Ulithian, Saipan Carolinian and Chuukic. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: # Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. ® Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper lefr-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or microfiche but lack the clarity on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, 35mm slides of 6”x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography. Farslow, Daniel Leslie THE BEHAVIOR AND ECOLOGY OF THE LONG-TAILED MACAQUE (MACACA FASCICULARIS) ON ANGAUR ISLAND, PALAU, MICRONESIA The Ohio State University Ph.D. 1987 University Microfilms I n ter n ât i O n siSOO N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor. Ml 48106 PLEASE NOTE; In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

Heritage and Communities in Palau

MICRONESIAN JOURNAL OF THE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Vol. 5, nº 1/2 Combined Issue November 2006 CULTURAL HERITAGE AND COMMUNITIES IN PALAU Rita Olsudong Bureau of Arts and Culture/ Palau Historic Preservation Office , Palau The increase of population including Palauans and foreigners in the Republic of Palau is a threat to the protection and preservation of historic properties that Palau Historic Preservation has to address. The population increases is compet- ing with land use that hold the historic properties. Increase of foreign contact and ideals are undermining the cultural sensitivity that stimulate Palauans, the stakeholders of the historic properties to consider the properties as obstacles or nuisance that have to be got rid of. Palau Historic Preservation Office is struggling to alleviate this threat with small staff and funding For this paper I would like to concentrate on in northwest to southeast direction and 25 threats or a challenges that Palau Historic Pres- kilometers at its widest. Most of the islands are ervation office is facing in protection and pres- encompassed in a barrier reef except for Kay- ervation of Palau cultural heritage. Increase in angel islands to the north and Angaur and human population is an increase in develop- Southwest Island group to the south. The ments that demand more land space threaten- Southwest Island group is located approxi- ing cultural landscapes that hold historic mately 389 kilometers south of the main archi- properties. Palau population is increasing pelago. The inhabited islands of Palau included every year that includes both Palauans and for- from north to south: Kayangel, Babeldaob, eigners. -

Saipan Carolinian, One Chuukic Language Blended from Many (PDF)

SAIPAN CAROLINIAN, ONE CHUUKIC LANGUAGE BLENDED FROM MANY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS DECEMBER 2012 BY S. JAMES ELLIS Dissertation Committee: Kenneth L. Rehg, Chairperson Byron W. Bender William D. O‘Grady Yuko Otsuka David L. Hanlon Keywords: Saipan Carolinian, Blended Language, Chuukic, dialect chain, Carolinian language continuum, Language Bending, Micronesia i © Copyright 2012 by S. James Ellis ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS No section of this extensive study is more difficult than this one. There is such a great number of Carolinians, many no longer with us, and many other friends who have had an important part of my life and this work. And yet, in view of the typical rush to submit this just under the wire, many of you will be unintentionally missed. I can only apologize to those of you whose names I fail to list here, and I can only promise that when this dissertation is properly published, in due time, I will include you and recognize your valuable contribution. Those that come to mind, however, as of this writing, are Jesus Elameto and his wife, Vicky, who were the first Carolinians I met, and who made me an always-welcome member of the family, and cheerfully assisted and supported every aspect of my work through all these years. During those early days of intelligibility-testing research in the late 80s I also want to mention the role of Project Beam and the Jesuit community and the string of contacts made possible through our common interest in maintaining Carolinian languages. -

12Th BELAU NATIONAL GAMES JUNE 22 RESULTS

12th BELAU NATIONAL GAMES JUNE 22 RESULTS BASKETBALL SEMI FINALS WGM 62 PB#1 - WGM 65 PA#2 - Women S. 70 13:00 72 v 34 Ngaraard Sonsorol Finals Men Semi 71 15:00 MGM 66 PB#1 - Ngaraard 93 v MGM 69 PA#2 - Koror 85 22- Finals Sat Jun Women S. 72 17:00 WGM 63 PA#1 - Koror 52 v WGM 64 PB#2 - Peleliu 67 Finals Men Semi 73 19:00 MGM 67 PA#1 - Angaur 64 v MGM 68 PB#2 - Peleliu 50 Finals SOFTBALL 6/22 - Sat 2:00pm PELELIU (W) 14 VS AIMELIIK (W) 2 consolation 6/22 - Sat 3:40pm KOROR (M) 1 VS NGARDMAU (M) 8 consolation 6/22 - Sat 5:20pm PELELIU (W) 8 VS KOROR (W) 7 championship 6/22 - Sat 7:00pm PELELIU (M) 12 VS NGARDMAU (M) 5 championship MEN WOMEN PELELIU PELELIU NGARDMAU KOROR KOROR AIMELIIK VOLLEYBALL MEN'S VOLLEYBALL RESUTLS - JUNE 22 GAME NO. TEAM SCORE TEAM SCORE 1 KOROR 24 25 25 NGARDMAU 26 18 23 2 NGARCHELONG 25 25 NGIWAL 20 18 3 PELELIU 27 23 29 VS AIMELIIK 25 25 31 4 NGARAARD 25 15 25 NGCHESAR 17 25 17 5 NGARDMAU 25 25 NGIWAL 17 20 6 HATOHOBEI 19 25 21 AIMELIIK 25 23 25 PLAYOFF ANGAUR 25 25 AIMELIIK 11 20 PLAYOFF KOROR 25 16 25 NGEREMLENGUI 18 25 19 Palau Swimming Association ST HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 6.0 - 7:01 PM 6/22/2019 Page 1 2019 Belau Games - 6/19/2019 to 6/22/2019 Results - Open Water Event 114 Boys 9 & Under 300 Open Water Name Age Team Seed Time Finals Time 1 Gibbons, Charlie 9 Koror NT 10:29.82 Event 116 Boys 10-13 300 Open Water Name Age Team Seed Time Finals Time 1 Nestor, Kazuumi 10 Airai NT 9:12.48 2 Keane, Brendan 10 Airai NT 9:42.11 3 Allen, Kobe 12 Kayangel NT 11:07.25 Event 117 Girls 10-13 750 Open Water Name Age -

Palauan English As a Newly Emerging Postcolonial Variety in the Pacifi C*

Palauan English as a newly emerging postcolonial variety in the Pacifi c* Kazuko Matsumoto・David Britain 1. Introduction The Republic of Palau/Beluu ęr a Belau is an independent nation state of the Western Pacifi c, consisting of an archipelago of around 350 small islands stretched across 400 miles of ocean. Its nearest neighbours are Indonesia and Papua New Guinea to the south, the Federated States of Micronesia to the east, Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands to the northeast, and the Philippines to the west. The islands have a population of around 20,000, of which over 60% live in the largest city and former capital of Koror in 2005 (Offi ce of Planing and Statistics 2006: 23). The capital, in 2006, was moved to Ngerulmud, in Melekeok State on the main island of Babeldaob. For most of the 20th century, Palau was under colonial administration: by Spain (1885–1899), Germany (1899–1914), Japan (1914–1945), and fi nally, the United States of America (1945–1994). It formally gained its independence in 1994. This article examines the emergence of an Anglophone speech community in Palau, and aims to do three things: firstly to set the emergence of Palauan English into the context of the country’s complex colonial past. Palau’s four colonial rulers have exercised control in different ways, with different degrees of settler migration, different attitudes towards the function of Palau as a ‘colony’, and widely differing local policies, leading to very different linguistic outcomes in each case. The article focusses, however, on the American era and the path to Palauan independence.