61-926 MCKNIGHT, Robert Kellogg. COMPETITION in PALAU. The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

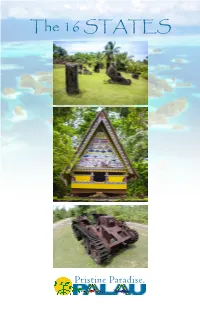

The 16 STATES

The 16 STATES Pristine Paradise. 2 Palau is an archipelago of diverse terrain, flora and fauna. There is the largest island of volcanic origin, called Babeldaob, the outer atoll and limestone islands, the Southern Lagoon and islands of Koror, and the southwest islands, which are located about 250 miles southwest of Palau. These regions are divided into sixteen states, each with their own distinct features and attractions. Transportation to these states is mainly by road, boat, or small aircraft. Koror is a group of islands connected by bridges and causeways, and is joined to Babeldaob Island by the Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge. Once in Babeldaob, driving the circumference of the island on the highway can be done in a half day or full day, depending on the number of stops you would like. The outer islands of Angaur and Peleliu are at the southern region of the archipelago, and are accessable by small aircraft or boat, and there is a regularly scheduled state ferry that stops at both islands. Kayangel, to the north of Babeldaob, can also be visited by boat or helicopter. The Southwest Islands, due to their remote location, are only accessible by large ocean-going vessels, but are a glimpse into Palau’s simplicity and beauty. When visiting these pristine areas, it is necessary to contact the State Offices in order to be introduced to these cultural treasures through a knowledgeable guide. While some fees may apply, your contribution will be used for the preservation of these sites. Please see page 19 for a list of the state offices. -

The Republic of Palau Pursuing a Sustainable and Resilient Energy Future

OIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIA The Republic of Palau Pursuing a Sustainable and Resilient Energy Future The Republic of Palau is located roughly 500 miles east of the Philippines in the Western Pacific Ocean. The country consists of 189 square miles of land spread over more than 340 islands, only nine of which are inhabited: 95% of the land area lies within a single reef structure that includes the islands of Babeldaob (a.k.a. Babelthuap), Peleliu and Koror. Palau and the United States have a strong relationship as enshrined in the Compact of Free Association, U.S. Public Law 99-658. Palau has made a concerted effort in goals set forth in its energy policy. recent years to address the technical, The country completed its National policy, social and economic hurdles Climate Change Policy in 2015 and Energy & Climate Facts to deploying energy efficiency and made a commitment to reduce Total capacity (2015): 40.1 MW renewable energy technologies, and has national greenhouse gas emissions Diesel: 38.8 MW taken measures to mitigate and adapt to (GHGs) as part of the United Nations Solar PV: 1.3 MW climate change. This work is grounded in Framework Convention on Climate Total generation (2014): 78,133 MWh Palau’s 2010 National Energy Policy. Change (UNFCCC). Demand for electricity (2015): Palau has also developed an energy action However with a population of just Average/Peak: 8.9/13.5 MW plan to outline concrete steps the island over 21,000 and a gross national GHG emissions per capita: 13.56 tCO₂e nation could take to achieve the energy income per capita of only US$11,110 (2011) in 2014, Palau will need assistance Residential electric rate: $0.28/kWh 7°45|N (2013 average) Arekalong from the international community in REPUBLIC Peninsula order to fully implement its energy Population (2015): 21,265 OF PALAU and climate goals. -

Heraldic Terms

HERALDIC TERMS The following terms, and their definitions, are used in heraldry. Some terms and practices were used in period real-world heraldry only. Some terms and practices are used in modern real-world heraldry only. Other terms and practices are used in SCA heraldry only. Most are used in both real-world and SCA heraldry. All are presented here as an aid to heraldic research and education. A LA CUISSE, A LA QUISE - at the thigh ABAISED, ABAISSÉ, ABASED - a charge or element depicted lower than its normal position ABATEMENTS - marks of disgrace placed on the shield of an offender of the law. There are extreme few records of such being employed, and then only noted in rolls. (As who would display their device if it had an abatement on it?) ABISME - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ABOUTÉ - end to end ABOVE - an ambiguous term which should be avoided in blazon. Generally, two charges one of which is above the other on the field can be blazoned better as "in pale an X and a Y" or "an A and in chief a B". See atop, ensigned. ABYSS - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ACCOLLÉ - (1) two shields side-by-side, sometimes united by their bottom tips overlapping or being connected to each other by their sides; (2) an animal with a crown, collar or other item around its neck; (3) keys, weapons or other implements placed saltirewise behind the shield in a heraldic display. -

A Summary of Palau's Typhoon History 1945-2013

A Summary of Palau’s Typhoon History 1945-2013 Coral Reef Research Foundation, Palau Dec, 2014 © Coral Reef Research Foundation 2014 Suggested citation: Coral Reef Research Foundation, 2014. A Summary of Palau’s Typhoon History. Technical Report, 17pp. www.coralreefpalau.org Additions and suggestions welcome. Please email: [email protected] 2 Summary: Since 1945 Palau has had 68 recorded typhoons, tropical storms or tropical depressions come within 200 nmi of its islands or reefs. At their nearest point to Palau, 20 of these were typhoon strength with winds ≥64kts, or an average of 1 typhoon every 3 years. November and December had the highest number of significant storms; July had none over 40 kts and August had no recorded storms. Data Compilation: Storms within 200 nmi (nautical miles) of Palau were identified from the Digital Typhoon, National Institute of Informatics, Japan web site (http://agora.ex.nii.ac.jp/digital- typhoon/reference/besttrack.html.en). The storm tracks and intensities were then obtained from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) (https://metoc.ndbc.noaa.gov/en/JTWC/). Three storm categories were used following the JTWC: Tropical Depression, winds ≤ 33 kts; Tropical Storm, winds 34-63 kts; Typhoon ≥64kts. All track data was from the JTWC archives. Tracks were plotted on Google Earth and the nearest distance to land or reef, and bearing from Palau, were measured; maximum sustained wind speed in knots (nautical miles/hr) at that point was recorded. Typhoon names were taken from the Digital Typhoon site, but typhoon numbers for the same typhoon were from the JTWC archives. -

Republic of Palau

REPUBLIC OF PALAU Palau Public Library Five-Year State Plan 2020-2022 For submission to the Institute of Museum and Library Services Submitted by: Palau Public Library Ministry of Education Republic of Palau 96940 April 22, 2019 Palau Five-Year Plan 1 2020-2022 MISSION The Palau Public Library is to serve as a gateway for lifelong learning and easy access to a wide range of information resources and to ensure the residents of Palau will be successful, literate and resourceful in the Palauan society and the world. PALAU PUBLIC LIBRARY BACKGROUND The Palau Public Library (PPL), was established in 1964, comes under the Ministry of Education. It is the only public library in the Republic of Palau, with collections totaling more than 20,000. The library has three full-time staff, the Librarian, the Library Assistant, and the Library Aide/Bookmobile Operator. The mission of the PPL is to serve as a gateway to lifelong learning and easy access to a wide range of information resources to ensure the residents of Palau will be successful, literate, and resourceful in the Palauan society and world. The PPL strives to provide access to materials, information resources, and services for community residents of all ages for professional and personal development, enjoyment, and educational needs. In addition, the library provides access to EBSCOHost databases and links to open access sources of scholarly information. It seeks to promote easy access to a wide range of resources and information and to create activities and programs for all residents of Palau. The PPL serves as the library for Palau High School, the only public high school in the Republic of Palau. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) CbfotfZ 3^3 / UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC QNGSLULIJUL AND/OR COMMON same LOCATION STREET& NUMBER Uehuladokoe __NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Melekeok VICINITY OF Babelthuap Island___________ STATE Palau Districtf Trust CODETerritory J of the PacificCOUNTY Islands 96950CODE CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT X-PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —2JJNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _?SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT _RELIGIOUS OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO, —MILITARY XOTHER: storage [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Trust Territory Government/in trust tc? Chief Reklai STREET & NUMBER Okemii Saipan Headquarters Palau District CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Municipal Office STREET & NUMBER Ngerams CITY, TOWN STATE Melekeok, Babelthuap Island^ TTPI 96950 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE none, DATE —FEDERAL —STATE _COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD X_RUINS _ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED ——————————DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Ongeluluul is a stone platform along the main road te£ Old Melekeok Village to west/southwest further inland about 100 yards from the boathouse along ttef shoreline. The platform is about EO feet by 20 feet separate from the main road by a small creek paralleling the road eastward. -

The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau

THE BIOARCHAEOLOGY OF INITIAL HUMAN SETTLEMENT IN PALAU, WESTERN MICRONESIA by JESSICA H. STONE A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2020 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Jessica H. Stone Title: The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau, Western Micronesia This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Anthropology by: Scott M. Fitzpatrick Chairperson Nelson Ting Core Member Dennis H. O’Rourke Core Member Stephen R. Frost Core Member James Watkins Institutional Representative and Kate Mondloch Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2020 ii © 2020 Jessica H. Stone iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Jessica H. Stone Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology June 2020 Title: The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau, Western Micronesia The initial settlement of Remote Oceania represents the world’s last major wave of human dispersal. While transdisciplinary models involving linguistic, archaeological, and biological data have been utilized in the Pacific to develop basic chronologies and trajectories of initial human settlement, a number of elusive gaps remain in our understanding of the region’s colonization history. This is especially true in Micronesia, where a paucity of human skeletal material dating to the earliest periods of settlement have hindered biological contributions to colonization models. The Chelechol ra Orrak site in Palau, western Micronesia, contains the largest and oldest human skeletal assemblage in the region, and is one of only two known sites that represent some of the earliest settlers in the Pacific. -

Genocide and the Indians of California, 1769-1873 Margaret A

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Graduate Masters Theses Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses 5-1993 Genocide and the Indians of California, 1769-1873 Margaret A. Field University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses Part of the Native American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Field, Margaret A., "Genocide and the Indians of California, 1769-1873" (1993). Graduate Masters Theses. Paper 141. This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENOCIDE AND THE INDIANS OF CALIFORNIA , 1769-1873 A Thesis Presented by MARGARET A. FIELD Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies and Research of the Un1versity of Massachusetts at Boston in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS MAY 1993 HISTCRY PROGRAM GENOCIDE AND THE I NDIAN S OF CALIFORNIA, 1769-187 3 A Thesis P resented by MARGARET A. FIELD Approved as to style and content by : Clive Foss , Professor Co - Chairperson of Committee mes M. O'Too le , Assistant Professor -Chairpers on o f Committee Memb e r Ma rshall S. Shatz, Pr og~am Director Department of History ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank professors Foss , O'Toole, and Buckley f or their assistance in preparing this manuscri pt and for their encouragement throughout the project . -

The Indian Shaker Church in the Canada-US Pacific Northwest

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Scholars Commons Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier History Faculty Publications History 4-1-2011 Shaking Up Christianity: The Indian Shaker Church in the Canada- U.S. Pacific Northwest Susan Neylan Wilfrid Laurier University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/hist_faculty Recommended Citation Neylan, Susan, "Shaking Up Christianity: The Indian Shaker Church in the Canada-U.S. Pacific Northwest" (2011). History Faculty Publications. 16. https://scholars.wlu.ca/hist_faculty/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shaking Up Christianity: The Indian Shaker Church in the Canada-U.S. Pacific Northwest* Susan Neylan / Wilfrid Laurier University The National Film Board of Canada documentary film O’Siem opens with a contemporary Native American man, Gene Harry, singing and passing his hands over the body of a badly injured man lying unconscious in a hospital bed.1 Harry is an Indian Shaker Church minister and, as he describes his approach to healing this man, the juxtaposition between native and Christian spirit ways is apparent: The first time I got a call from Will’s brother Joe, he said that he had a few hours to be with us. When I entered the door and saw the condition of Will, burnt up in a fire, bandaged from his knees to his head, I was shaking inside. -

TARDIVEL-THESIS-2019.Pdf (1.146Mb)

NAVIGATING INDIGENOUS LEADERSHIP IN A SETTLER COLONIAL WORLD: RON AND PATRICIA JOHN ‘COME HOME’ TO STÓ:LÕ POLITICS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE COLLEGE OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN SASKATOON By Angélique Tardivel © Copyright Angélique Tardivel, April 2019. All rights reserved PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Reference in this thesis to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the University of Saskatchewan. The views and opinions of the author do not state or reflect those of the University of Saskatchewan, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. -

2016 Palau 24 Civil Appeal No

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF PALAU APPELLATE DIVISION NGEREMLENGUI STATE GOVERNMENT and NGEREMLENGUI STATE PUBLIC LANDS AUTHORITY, Appellants/Cross-Appellees, v. NGARDMAU STATE GOVERNMENT and NGARDMAU STATE PUBLIC LANDS AUTHORITY, Appellees/Cross-Appellants. Cite as: 2016 Palau 24 Civil Appeal No. 15-014 Appeal from Civil Action No. 13-020 Decided: November 16, 2016 Counsel for Ngeremlengui ............................................... Oldiais Ngiraikelau Counsel for Ngardmau ..................................................... Yukiwo P. Dengokl Matthew S. Kane BEFORE: KATHLEEN M. SALII, Associate Justice LOURDES F. MATERNE, Associate Justice C. QUAY POLLOI, Associate Justice Pro Tem Appeal from the Trial Division, the Honorable R. Ashby Pate, Associate Justice, presiding. OPINION PER CURIAM: [¶ 1] This appeal arises from a dispute between the neighboring States of Ngeremlengui and Ngardmau regarding their common boundary line. In 2013, the Ngeremlengui State Government and Ngeremlengui State Public Lands Authority (Ngeremlengui) filed a civil suit against the Ngardmau State Government and Ngardmau State Public Lands Authority (Ngardmau), seeking a judgment declaring the legal boundary line between the two states. After extensive evidentiary proceedings and a trial, the Trial Division issued a decision adjudging that common boundary line. [¶ 2] Each state has appealed a portion of that decision and judgment. Ngardmau argues that the Trial Division applied an incorrect legal standard to determine the boundary line. Ngardmau also argues that the Trial Division Ngeremlengui v. Ngardmau, 2016 Palau 24 clearly erred in making factual determinations concerning parts of the common land boundary. Ngeremlengui argues that the Trial Division clearly erred in making factual determinations concerning a part of the common maritime boundary. For the reasons below, the judgment of the Trial Division is AFFIRMED. -

Heraldry: Where Art and Family History Meet Part II: Marshalling and Cadency by Richard A

Heraldry: Where Art and Family History Meet Part II: Marshalling and Cadency by Richard A. McFarlane, J.D., Ph.D. Heraldry: Where Art and Family History Meet 1 Part II: Marshalling and Cadency © Richard A. McFarlane (2015) Marshalling is — 1 Marshalling is the combining of multiple coats of arms into one achievement to show decent from multiple armigerous families, marriage between two armigerous families, or holding an office. Marshalling is accomplished in one of three ways: dimidiation, impalement, and 1 Image: The arms of Edward William Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. Blazon: Quarterly: 1st, Gules a Bend between six Cross Crosslets fitchée Argent, on the bend (as an Honourable Augmentation) an Escutcheon Or charged with a Demi-Lion rampant pierced through the mouth by an Arrow within a Double Tressure flory counter-flory of the first (Howard); 2nd, Gules three Lions passant guardant in pale Or in chief a Label of three points Argent (Plantagenet of Norfolk); 3rd, Checky Or and Azure (Warren); 4th, Gules a Lion rampant Or (Fitzalan); behind the shield two gold batons in saltire, enamelled at the ends Sable (as Earl Marshal). Crests: 1st, issuant from a Ducal Coronet Or a Pair of Wings Gules each charged with a Bend between six Cross Crosslets fitchée Argent (Howard); 2nd, on a Chapeau Gules turned up Ermine a Lion statant guardant with tail extended Or ducally gorged Argent (Plantagenet of Norfolk); 3rd, on a Mount Vert a Horse passant Argent holding in his mouth a Slip of Oak Vert fructed proper (Fitzalan) Supporters: Dexter: a Lion Argent; Sinister: a Horse Argent holding in his mouth a Slip of Oak Vert fructed proper.