Mapping Mammalian Cell-Type-Specific Transcriptional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4-6 Weeks Old Female C57BL/6 Mice Obtained from Jackson Labs Were Used for Cell Isolation

Methods Mice: 4-6 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice obtained from Jackson labs were used for cell isolation. Female Foxp3-IRES-GFP reporter mice (1), backcrossed to B6/C57 background for 10 generations, were used for the isolation of naïve CD4 and naïve CD8 cells for the RNAseq experiments. The mice were housed in pathogen-free animal facility in the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology and were used according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and use Committee. Preparation of cells: Subsets of thymocytes were isolated by cell sorting as previously described (2), after cell surface staining using CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD3ε (145- 2C11), CD24 (M1/69) (all from Biolegend). DP cells: CD4+CD8 int/hi; CD4 SP cells: CD4CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo; CD8 SP cells: CD8 int/hi CD4 CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo (Fig S2). Peripheral subsets were isolated after pooling spleen and lymph nodes. T cells were enriched by negative isolation using Dynabeads (Dynabeads untouched mouse T cells, 11413D, Invitrogen). After surface staining for CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD62L (MEL-14), CD25 (PC61) and CD44 (IM7), naïve CD4+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo and naïve CD8+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo were obtained by sorting (BD FACS Aria). Additionally, for the RNAseq experiments, CD4 and CD8 naïve cells were isolated by sorting T cells from the Foxp3- IRES-GFP mice: CD4+CD62LhiCD25–CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– and CD8+CD62LhiCD25– CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– (antibodies were from Biolegend). In some cases, naïve CD4 cells were cultured in vitro under Th1 or Th2 polarizing conditions (3, 4). -

Supplemental Materials ZNF281 Enhances Cardiac Reprogramming

Supplemental Materials ZNF281 enhances cardiac reprogramming by modulating cardiac and inflammatory gene expression Huanyu Zhou, Maria Gabriela Morales, Hisayuki Hashimoto, Matthew E. Dickson, Kunhua Song, Wenduo Ye, Min S. Kim, Hanspeter Niederstrasser, Zhaoning Wang, Beibei Chen, Bruce A. Posner, Rhonda Bassel-Duby and Eric N. Olson Supplemental Table 1; related to Figure 1. Supplemental Table 2; related to Figure 1. Supplemental Table 3; related to the “quantitative mRNA measurement” in Materials and Methods section. Supplemental Table 4; related to the “ChIP-seq, gene ontology and pathway analysis” and “RNA-seq” and gene ontology analysis” in Materials and Methods section. Supplemental Figure S1; related to Figure 1. Supplemental Figure S2; related to Figure 2. Supplemental Figure S3; related to Figure 3. Supplemental Figure S4; related to Figure 4. Supplemental Figure S5; related to Figure 6. Supplemental Table S1. Genes included in human retroviral ORF cDNA library. Gene Gene Gene Gene Gene Gene Gene Gene Symbol Symbol Symbol Symbol Symbol Symbol Symbol Symbol AATF BMP8A CEBPE CTNNB1 ESR2 GDF3 HOXA5 IL17D ADIPOQ BRPF1 CEBPG CUX1 ESRRA GDF6 HOXA6 IL17F ADNP BRPF3 CERS1 CX3CL1 ETS1 GIN1 HOXA7 IL18 AEBP1 BUD31 CERS2 CXCL10 ETS2 GLIS3 HOXB1 IL19 AFF4 C17ORF77 CERS4 CXCL11 ETV3 GMEB1 HOXB13 IL1A AHR C1QTNF4 CFL2 CXCL12 ETV7 GPBP1 HOXB5 IL1B AIMP1 C21ORF66 CHIA CXCL13 FAM3B GPER HOXB6 IL1F3 ALS2CR8 CBFA2T2 CIR1 CXCL14 FAM3D GPI HOXB7 IL1F5 ALX1 CBFA2T3 CITED1 CXCL16 FASLG GREM1 HOXB9 IL1F6 ARGFX CBFB CITED2 CXCL3 FBLN1 GREM2 HOXC4 IL1F7 -

Supp Table 1.Pdf

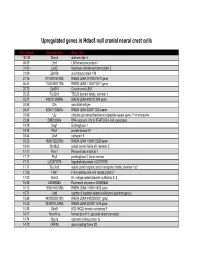

Upregulated genes in Hdac8 null cranial neural crest cells fold change Gene Symbol Gene Title 134.39 Stmn4 stathmin-like 4 46.05 Lhx1 LIM homeobox protein 1 31.45 Lect2 leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 31.09 Zfp108 zinc finger protein 108 27.74 0710007G10Rik RIKEN cDNA 0710007G10 gene 26.31 1700019O17Rik RIKEN cDNA 1700019O17 gene 25.72 Cyb561 Cytochrome b-561 25.35 Tsc22d1 TSC22 domain family, member 1 25.27 4921513I08Rik RIKEN cDNA 4921513I08 gene 24.58 Ofa oncofetal antigen 24.47 B230112I24Rik RIKEN cDNA B230112I24 gene 23.86 Uty ubiquitously transcribed tetratricopeptide repeat gene, Y chromosome 22.84 D8Ertd268e DNA segment, Chr 8, ERATO Doi 268, expressed 19.78 Dag1 Dystroglycan 1 19.74 Pkn1 protein kinase N1 18.64 Cts8 cathepsin 8 18.23 1500012D20Rik RIKEN cDNA 1500012D20 gene 18.09 Slc43a2 solute carrier family 43, member 2 17.17 Pcm1 Pericentriolar material 1 17.17 Prg2 proteoglycan 2, bone marrow 17.11 LOC671579 hypothetical protein LOC671579 17.11 Slco1a5 solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1a5 17.02 Fbxl7 F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 7 17.02 Kcns2 K+ voltage-gated channel, subfamily S, 2 16.93 AW493845 Expressed sequence AW493845 16.12 1600014K23Rik RIKEN cDNA 1600014K23 gene 15.71 Cst8 cystatin 8 (cystatin-related epididymal spermatogenic) 15.68 4922502D21Rik RIKEN cDNA 4922502D21 gene 15.32 2810011L19Rik RIKEN cDNA 2810011L19 gene 15.08 Btbd9 BTB (POZ) domain containing 9 14.77 Hoxa11os homeo box A11, opposite strand transcript 14.74 Obp1a odorant binding protein Ia 14.72 ORF28 open reading -

Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis of KRAS Mutant Cell Lines Ben Yi Tew1,5, Joel K

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of KRAS mutant cell lines Ben Yi Tew1,5, Joel K. Durand2,5, Kirsten L. Bryant2, Tikvah K. Hayes2, Sen Peng3, Nhan L. Tran4, Gerald C. Gooden1, David N. Buckley1, Channing J. Der2, Albert S. Baldwin2 ✉ & Bodour Salhia1 ✉ Oncogenic RAS mutations are associated with DNA methylation changes that alter gene expression to drive cancer. Recent studies suggest that DNA methylation changes may be stochastic in nature, while other groups propose distinct signaling pathways responsible for aberrant methylation. Better understanding of DNA methylation events associated with oncogenic KRAS expression could enhance therapeutic approaches. Here we analyzed the basal CpG methylation of 11 KRAS-mutant and dependent pancreatic cancer cell lines and observed strikingly similar methylation patterns. KRAS knockdown resulted in unique methylation changes with limited overlap between each cell line. In KRAS-mutant Pa16C pancreatic cancer cells, while KRAS knockdown resulted in over 8,000 diferentially methylated (DM) CpGs, treatment with the ERK1/2-selective inhibitor SCH772984 showed less than 40 DM CpGs, suggesting that ERK is not a broadly active driver of KRAS-associated DNA methylation. KRAS G12V overexpression in an isogenic lung model reveals >50,600 DM CpGs compared to non-transformed controls. In lung and pancreatic cells, gene ontology analyses of DM promoters show an enrichment for genes involved in diferentiation and development. Taken all together, KRAS-mediated DNA methylation are stochastic and independent of canonical downstream efector signaling. These epigenetically altered genes associated with KRAS expression could represent potential therapeutic targets in KRAS-driven cancer. Activating KRAS mutations can be found in nearly 25 percent of all cancers1. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

1714 Gene Comprehensive Cancer Panel Enriched for Clinically Actionable Genes with Additional Biologically Relevant Genes 400-500X Average Coverage on Tumor

xO GENE PANEL 1714 gene comprehensive cancer panel enriched for clinically actionable genes with additional biologically relevant genes 400-500x average coverage on tumor Genes A-C Genes D-F Genes G-I Genes J-L AATK ATAD2B BTG1 CDH7 CREM DACH1 EPHA1 FES G6PC3 HGF IL18RAP JADE1 LMO1 ABCA1 ATF1 BTG2 CDK1 CRHR1 DACH2 EPHA2 FEV G6PD HIF1A IL1R1 JAK1 LMO2 ABCB1 ATM BTG3 CDK10 CRK DAXX EPHA3 FGF1 GAB1 HIF1AN IL1R2 JAK2 LMO7 ABCB11 ATR BTK CDK11A CRKL DBH EPHA4 FGF10 GAB2 HIST1H1E IL1RAP JAK3 LMTK2 ABCB4 ATRX BTRC CDK11B CRLF2 DCC EPHA5 FGF11 GABPA HIST1H3B IL20RA JARID2 LMTK3 ABCC1 AURKA BUB1 CDK12 CRTC1 DCUN1D1 EPHA6 FGF12 GALNT12 HIST1H4E IL20RB JAZF1 LPHN2 ABCC2 AURKB BUB1B CDK13 CRTC2 DCUN1D2 EPHA7 FGF13 GATA1 HLA-A IL21R JMJD1C LPHN3 ABCG1 AURKC BUB3 CDK14 CRTC3 DDB2 EPHA8 FGF14 GATA2 HLA-B IL22RA1 JMJD4 LPP ABCG2 AXIN1 C11orf30 CDK15 CSF1 DDIT3 EPHB1 FGF16 GATA3 HLF IL22RA2 JMJD6 LRP1B ABI1 AXIN2 CACNA1C CDK16 CSF1R DDR1 EPHB2 FGF17 GATA5 HLTF IL23R JMJD7 LRP5 ABL1 AXL CACNA1S CDK17 CSF2RA DDR2 EPHB3 FGF18 GATA6 HMGA1 IL2RA JMJD8 LRP6 ABL2 B2M CACNB2 CDK18 CSF2RB DDX3X EPHB4 FGF19 GDNF HMGA2 IL2RB JUN LRRK2 ACE BABAM1 CADM2 CDK19 CSF3R DDX5 EPHB6 FGF2 GFI1 HMGCR IL2RG JUNB LSM1 ACSL6 BACH1 CALR CDK2 CSK DDX6 EPOR FGF20 GFI1B HNF1A IL3 JUND LTK ACTA2 BACH2 CAMTA1 CDK20 CSNK1D DEK ERBB2 FGF21 GFRA4 HNF1B IL3RA JUP LYL1 ACTC1 BAG4 CAPRIN2 CDK3 CSNK1E DHFR ERBB3 FGF22 GGCX HNRNPA3 IL4R KAT2A LYN ACVR1 BAI3 CARD10 CDK4 CTCF DHH ERBB4 FGF23 GHR HOXA10 IL5RA KAT2B LZTR1 ACVR1B BAP1 CARD11 CDK5 CTCFL DIAPH1 ERCC1 FGF3 GID4 HOXA11 IL6R KAT5 ACVR2A -

C/Ebpα Is an Essential Collaborator in Hoxa9/Meis1-Mediated Leukemogenesis

C/EBPα is an essential collaborator in Hoxa9/Meis1-mediated leukemogenesis Cailin Collinsa, Jingya Wanga, Hongzhi Miaoa, Joel Bronsteina, Humaira Nawera, Tao Xua, Maria Figueroaa, Andrew G. Munteana, and Jay L. Hessa,b,1 aDepartment of Pathology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109; and bIndiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202 Edited* by Louis M. Staudt, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, and approved May 19, 2014 (received for review February 12, 2014) Homeobox A9 (HOXA9) is a homeodomain-containing transcrip- with Hoxa9. In addition, C/EBP recognition motifs are enriched tion factor that plays a key role in hematopoietic stem cell expan- at Hoxa9 binding sites. sion and is commonly deregulated in human acute leukemias. A C/EBPα is a basic leucine-zipper transcription factor that plays variety of upstream genetic alterations in acute myeloid leukemia a critical role in lineage commitment during hematopoietic dif- −/− (AML) lead to overexpression of HOXA9, almost always in associ- ferentiation (18). Whereas Cebpa mice show complete loss of ation with overexpression of its cofactor meis homeobox 1 (MEIS1). the granulocytic compartment, recent work shows that loss of α A wide range of data suggests that HOXA9 and MEIS1 play a syn- C/EBP in adult HSCs leads to both an increase in the number ergistic causative role in AML, although the molecular mechanisms of functional HSCs and an increase in their proliferative and leading to transformation by HOXA9 and MEIS1 remain elusive. In repopulating capacity (19, 20). Conversely, CEBPA overexpression can promote transdifferentiation of a variety of fibroblastic cells to this study, we identify CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha (C/ the myeloid lineage and can induce monocytic differentiation in EBPα) as a critical collaborator required for Hoxa9/Meis1-mediated α MLL-fusion protein-mediated leukemias (21, 22). -

Novel Mutations in HSF4 Cause Congenital Cataracts in Chinese

Cao et al. BMC Medical Genetics (2018) 19:150 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-018-0636-3 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Novel mutations in HSF4 cause congenital cataracts in Chinese families Zongfu Cao2,3,4†, Yihua Zhu5†, Lijuan Liu6†, Shuangqing Wu7, Bing Liu5, Jianfu Zhuang8, Yi Tong5, Xiaole Chen1, Yongqing Xie1, Kaimei Nie1, Cailing Lu2,4,XuMa2,3,4* and Juhua Yang1* Abstract Background: Congenital cataract, a kind of cataract presenting at birth or during early childhood, is a leading cause of childhood blindness. To date, more than 30 genes on different chromosomes are known to cause this disorder. This study aimed to identify the HSF4 mutations in a cohort from Chinese families affected with congenital cataracts. Methods: Forty-two unrelated non-syndromic congenital cataract families and 112 ethnically matched controls from southeast China were recruited from the southeast of China. We employed Sanger sequencing method to discover the variants. To confirm the novel mutations, STR haplotypes were constructed to check the co- segregation with congenital cataract. The pathogenic potential of the novel mutations were assessed using bioinformatics tools including SIFT, Polyphen2, and Human Splicing Finder. The pathogenicity of all the mutations was evaluated by the guidelines of American College of Medical Genetics and InterVar software. Results: No previously reported HSF4 mutations were found in all the congenital cataract families. Five novel HSF4 mutations including c.187 T > C (p.Phe63Leu), c.218G > T (p.Arg73Leu), c.233A > G (p.Tyr78Cys), IVS5 c.233-1G > A and c.314G > C (p.Ser105Thr) were identified in five unrelated families with congenital cataracts, respectively. -

The Role of Constitutive Androstane Receptor and Estrogen Sulfotransferase in Energy Homeostasis

THE ROLE OF CONSTITUTIVE ANDROSTANE RECEPTOR AND ESTROGEN SULFOTRANSFERASE IN ENERGY HOMEOSTASIS by Jie Gao Bachelor of Engineering, China Pharmaceutical University, 1999 Master of Science, China Pharmaceutical University, 2002 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Pharmacy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH School of Pharmacy This dissertation was presented by Jie Gao It was defended on January 18, 2012 and approved by Billy W. Day, Professor, Pharmaceutical Sciences Donald B. DeFranco, Professor, Pharmacology & Chemical Biology Samuel M. Poloyac, Associate Professor, Pharmaceutical Sciences Song Li, Associate Professor, Pharmaceutical Sciences Dissertation Advisor: Wen Xie, Professor, Pharmaceutical Sciences ii Copyright © by Jie Gao 2012 iii THE ROLE OF CONSTITUTIVE ANDROSTANE RECEPTOR AND ESTROGEN SULFOTRANSFERASE IN ENERGY HOMEOSTASIS Jie Gao, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Obesity and type 2 diabetes are related metabolic disorders of high prevalence. The constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) was initially characterized as a xenobiotic receptor regulating the responses of mammals to xenotoxicants. In this study, I have uncovered an unexpected role of CAR in preventing obesity and alleviating type 2 diabetes. Activation of CAR prevented obesity and improved insulin sensitivity in both the HFD-induced type 2 diabetic model and the ob/ob mice. In contrast, CAR null mice maintained on a chow diet showed spontaneous insulin insensitivity. The metabolic benefits of CAR activation may have resulted from inhibition of hepatic lipogenesis and gluconeogenesis. The molecular mechanism through which CAR activation suppressed hepatic gluconeogenesis might be mediated via peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1α). -

What Your Genome Doesn't Tell

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Multi-layered epigenetic control of T cell fate decisions Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8rs7c7b3 Author Yu, Bingfei Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Multi-layered epigenetic control of T cell fate decisions A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Biology by Bingfei Yu Committee in charge: Professor Ananda Goldrath, Chair Professor John Chang Professor Stephen Hedrick Professor Cornelis Murre Professor Wei Wang 2018 Copyright Bingfei Yu, 2018 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Bingfei Yu is approved, and it is ac- ceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California San Diego 2018 iii DEDICATION To my parents who have been giving me countless love, trust and support to make me who I am. iv EPIGRAPH Stay hungary. Stay foolish. | Steve Jobs quoted from the back cover of the 1974 edition of the Whole Earth Catalog v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page.................................. iii Dedication..................................... iv Epigraph.....................................v Table of Contents................................. vi List of Figures.................................. ix Acknowledgements................................x Vita........................................ xii Abstract of -

Drosophila and Human Transcriptomic Data Mining Provides Evidence for Therapeutic

Drosophila and human transcriptomic data mining provides evidence for therapeutic mechanism of pentylenetetrazole in Down syndrome Author Abhay Sharma Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology Council of Scientific and Industrial Research Delhi University Campus, Mall Road Delhi 110007, India Tel: +91-11-27666156, Fax: +91-11-27662407 Email: [email protected] Nature Precedings : hdl:10101/npre.2010.4330.1 Posted 5 Apr 2010 Running head: Pentylenetetrazole mechanism in Down syndrome 1 Abstract Pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) has recently been found to ameliorate cognitive impairment in rodent models of Down syndrome (DS). The mechanism underlying PTZ’s therapeutic effect is however not clear. Microarray profiling has previously reported differential expression of genes in DS. No mammalian transcriptomic data on PTZ treatment however exists. Nevertheless, a Drosophila model inspired by rodent models of PTZ induced kindling plasticity has recently been described. Microarray profiling has shown PTZ’s downregulatory effect on gene expression in fly heads. In a comparative transcriptomics approach, I have analyzed the available microarray data in order to identify potential mechanism of PTZ action in DS. I find that transcriptomic correlates of chronic PTZ in Drosophila and DS counteract each other. A significant enrichment is observed between PTZ downregulated and DS upregulated genes, and a significant depletion between PTZ downregulated and DS dowwnregulated genes. Further, the common genes in PTZ Nature Precedings : hdl:10101/npre.2010.4330.1 Posted 5 Apr 2010 downregulated and DS upregulated sets show enrichment for MAP kinase pathway. My analysis suggests that downregulation of MAP kinase pathway may mediate therapeutic effect of PTZ in DS. Existing evidence implicating MAP kinase pathway in DS supports this observation. -

A Novel Missense Mutation in HSF4 Causes Autosomal-Dominant

Eye (2018) 32, 806–812 © 2018 Macmillan Publishers Limited, part of Springer Nature. All rights reserved 0950-222X/18 www.nature.com/eye 1,5 1,2,5 3,4 LABORATORY STUDY A novel missense V Berry , N Pontikos , A Moore , ACW Ionides3, V Plagnol2, ME Cheetham1 mutation in HSF4 and M Michaelides1,3 causes autosomal- dominant congenital lamellar cataract in a British family Abstract manifestations and is a predominant feature in 4200 genetic disorders. Congenital cataract may Purpose Inherited cataract, opacification of the lens, is the most common worldwide be familial and display considerable genotypic 4 cause of blindness in children. We aimed to and phenotypic heterogeneity. Inheritance is identify the genetic cause of isolated most commonly autosomal dominant (AD), 1 Department of Genetics, autosomal-dominant lamellar cataract in a usually with complete penetrance but with UCL Institute of five-generation British family. highly variable expressivity. The phenotypic Ophthalmology, London, fi UK Methods Whole exome sequencing (WES) classi cation of the cataract depends on the was performed on two affected individuals of position and type of the lens opacity such as: 2UCL Genetics Institute, the family and further validated by direct anterior polar, posterior polar, nuclear, lamellar, University College London, sequencing in family members. coralliform, blue-dot (cerulean), cortical, London UK Results A novel missense mutation pulverulent, polymorphic, complete cataract, 4 and posterior nuclear cataract.5,6 Significant 3 fi NM_001040667.2:c.190A G;p.K64E was Moor elds Eye Hospital, fi London, UK identi ed in the DNA-binding-domain of progress has been made in identifying the heat-shock transcription factor 4 (HSF4) and molecular genetic basis of human cataract.