Tunney Act Comments for Visa-Mastercard: Wildfang Exhibit 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

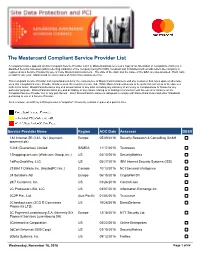

The Mastercard Compliant Service Provider List

The Mastercard Compliant Service Provider List A company’s name appears on this Compliant Service Provider List if (i) MasterCard has received a copy of an Attestation of Compliance (AOC) by a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA) reflecting validation of the company being PCI DSS compliant and (ii) MasterCard records reflect the company is registered as a Service Provider by one or more MasterCard Customers. The date of the AOC and the name of the QSA are also provided. Each AOC is valid for one year. MasterCard receives copies of AOCs from various sources. This Compliant Service Provider List is provided solely for the convenience of MasterCard Customers and any Customer that relies upon or otherwise uses this Compliant Service Provider list does so at the Customer’s sole risk. While MasterCard endeavors to keep the list current as of the date set forth in the footer, MasterCard disclaims any and all warranties of any kind, including any warranty of accuracy or completeness or fitness for any particular purpose. MasterCard disclaims any and all liability of any nature relating to or arising in connection with the use of or reliance on the Compliant Service Provider List or any part thereof. Each MasterCard Customer is obligated to comply with MasterCard Rules and other Standards pertaining to use of a Service Provider. As a reminder, an AOC by a QSA provides a “snapshot” of security controls in place at a point in time. Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV 1&1 Internet SE (1&1, 1&1 ipayment, Europe 05/09/2016 Security Research & Consulting GmbH ipayment.de) 1Link (Guarantee) Limited SAMEA 11/17/2015 Trustwave 1Shoppingcart.com (Web.com Group, lnc.) US 04/13/2016 SecurityMetrics 1stPayGateWay, LLC US 05/27/2016 IBM Internet Security Systems (ISS) 2138617 Ontario Inc. -

Registros De Entidades 2017

REGISTROS DE ENTIDADES 2017 SITUACION A 31 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2017 BANCO DE ESPAÑA INDICE Página CREDITO OFICIAL ORDENADO ALFABETICAMENTE ........................................................................................................ 9 ORDENADO POR CODIGO B.E. ......................................................................................................... 11 BANCOS ORDENADO ALFABETICAMENTE ...................................................................................................... 15 ORDENADO POR CODIGO B.E. ......................................................................................................... 17 CAJAS DE AHORROS ORDENADO ALFABETICAMENTE ...................................................................................................... 27 ORDENADO POR CODIGO B.E. ......................................................................................................... 29 COOPERATIVAS DE CREDITO ORDENADO ALFABETICAMENTE ...................................................................................................... 33 ORDENADO POR CODIGO B.E. ......................................................................................................... 35 ESTABLECIMIENTOS FINANCIEROS DE CREDITO ORDENADO ALFABETICAMENTE ...................................................................................................... 47 ORDENADO POR CODIGO B.E. ......................................................................................................... 49 ESTABLECIMIENTOS FINANCIEROS DE CREDITO -

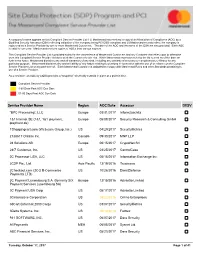

Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV

A company’s name appears on this Compliant Service Provider List if (i) Mastercard has received a copy of an Attestation of Compliance (AOC) by a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA) reflecting validation of the company being PCI DSS compliant and (ii) Mastercard records reflect the company is registered as a Service Provider by one or more Mastercard Customers. The date of the AOC and the name of the QSA are also provided. Each AOC is valid for one year. Mastercard receives copies of AOCs from various sources. This Compliant Service Provider List is provided solely for the convenience of Mastercard Customers and any Customer that relies upon or otherwise uses this Compliant Service Provider list does so at the Customer’s sole risk. While Mastercard endeavors to keep the list current as of the date set forth in the footer, Mastercard disclaims any and all warranties of any kind, including any warranty of accuracy or completeness or fitness for any particular purpose. Mastercard disclaims any and all liability of any nature relating to or arising in connection with the use of or reliance on the Compliant Service Provider List or any part thereof. Each Mastercard Customer is obligated to comply with Mastercard Rules and other Standards pertaining to use of a Service Provider. As a reminder, an AOC by a QSA provides a “snapshot” of security controls in place at a point in time. Compliant Service Provider 1-60 Days Past AOC Due Date 61-90 Days Past AOC Due Date Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV “BPC Processing”, LLC Europe 03/31/2017 Informzaschita 1&1 Internet SE (1&1, 1&1 ipayment, Europe 05/08/2017 Security Research & Consulting GmbH ipayment.de) 1Shoppingcart.com (Web.com Group, lnc.) US 04/29/2017 SecurityMetrics 2138617 Ontario Inc. -

Merchant Application and Agreement

Rev. NAPSTAND_ISO 10/2012 Page 8 TERMS AND CONDITIONS The Terms and Conditions together with the Application, pricing Schedule A, and any other documents referred to in Section 15.9 form the legal agreement between you (“Merchant”), Paymentech, LLC (“Chase Paymentech”), and JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. (“Member”) for processing your Payment Card Transactions. Chase Paymentech has agreed to acquire and process your Payment Card Transactions as well as pay you the amount of each Payment Card Transaction subject to the terms of this Agreement. You agree to pay us for the Services performed and to comply with the Payment Brand Rules, Security Standards, operating procedures and all applicable laws, as further described in this Agreement. The ISO listed on page 5 of the Application will be your source for all customer service matters. 1. MERCHANT’S ACCEPTANCE OF PAYMENT CARDS. 1.1 Exclusivity. During the term of this Agreement, Merchant must: (a) use exclusively Chase Paymentech for the Services; and (b) submit all Transaction Data to Chase Paymentech in compliance with all specified formats and procedures. 1.2 Payment Card Acceptance Policies and Prohibitions. Merchant must: (a) notify Chase Paymentech, on its Application or otherwise in writing, of all of Merchant’s Payment Card acceptance methods (e.g. card-present, card-not-present, recurring transactions, etc.); (b) accept all categories of Visa and MasterCard Payment Cards, unless Merchant has notified Chase Paymentech on its Application or otherwise in writing of Merchant’s election to accept one of the following “limited acceptance” options: i. Visa and MasterCard consumer credit (but not debit) cards and Visa and MasterCard commercial credit and debit cards only; or ii. -

3Q08 Earnings Press Release

JPMorgan Chase & Co. 270 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017-2070 NYSE symbol: JPM www.jpmorganchase.com News release: IMMEDIATE RELEASE JPMORGAN CHASE REPORTS THIRD-QUARTER 2008 NET INCOME OF $527 MILLION, OR $0.11 PER SHARE, INCLUDING ESTIMATED1 LOSSES OF $640 MILLION (AFTER-TAX) OR $0.18 PER SHARE FOR WASHINGTON MUTUAL MERGER-RELATED ITEMS • Acquired Washington Mutual’s banking operations on September 25: - Significantly strengthened consumer franchise, with more than 5,400 branches - Results included estimated1 losses of $640 million (after-tax) for Washington Mutual merger-related items: $1.2 billion charge to conform loan loss reserves and a $581 million extraordinary gain • Reported net markdowns of $3.6 billion due to mortgage-related positions and leveraged lending exposures in the Investment Bank • Maintained #1 rankings for Global Investment Banking Fees and Global Debt, Equity & Equity-related volumes for the quarter and year to date2 • Grew revenue by 16% and increased branch production at Retail Financial Services • Achieved double-digit net income growth at both Commercial Banking and Treasury & Securities Services • Reported the following significant after-tax items: - $927 million benefit from reduced deferred tax liabilities - $642 million loss on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac preferred securities - $248 million charge related to offer to repurchase auction-rate securities • Increased credit reserves by $1.3 billion firmwide to $15.3 billion, resulting in loan loss allowance coverage of 3.18% for consumer businesses and 2.11% for wholesale businesses, before Washington Mutual • Maintained strong Tier 1 Capital of $112 billion, or 8.9% (estimated); raised $11.5 billion of common equity during the quarter New York, October 15, 2008 – JPMorgan Chase & Co. -

JP Morgan Structured Products BV

Issuer J.P. Morgan Structured Products B.V. (Incorporated with limited liability in The Netherlands) Guarantor JPMorgan Chase Bank, National Association (a national banking association organized under the laws of United States of America) Managers J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd. J.P. Morgan Securities (Asia Pacific) Limited Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (the HKEx), The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the Stock Exchange) and Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this document, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this document. This document includes particulars given in compliance with the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the Stock Exchange’s Listing Rules) for the purpose of giving information with regard to the issuer, the guarantor and the structured products referred to in this document. The issuer and the guarantor accept full responsibility for the accuracy of the information contained in this document and confirm, having made all reasonable enquiries, that to the best of their knowledge and belief there are no other facts the omission of which would make any statement in this document misleading. We, the issuer of our structured products, are publishing this base listing document in order to obtain a listing on the Stock Exchange of our warrants and our equity linked instruments (the ELIs). We will refer to the warrants and the ELIs as “structured products” in this document. -

List of Participating Merchants Mastercard Automatic Billing Updater

List of Participating Merchants MasterCard Automatic Billing Updater 3801 Agoura Fitness 1835-180 MAIN STREET SUIT 247 Sports 5378 FAMILY FITNESS FREE 1870 AF Gilroy 2570 AF MAPLEWOOD SIMARD LIMITED 1881 AF Morgan Hill 2576 FITNESS PREMIER Mant (BISL) AUTO & GEN REC 190-Sovereign Society 2596 Fitness Premier Beec 794 FAMILY FITNESS N M 1931 AF Little Canada 2597 FITNESS PREMIER BOUR 5623 AF Purcellville 1935 POWERHOUSE FITNESS 2621 AF INDIANAPOLIS 1 BLOC LLC 195-Boom & Bust 2635 FAST FITNESS BOOTCAM 1&1 INTERNET INC 197-Strategic Investment 2697 Family Fitness Holla 1&1 Internet limited 1981 AF Stillwater 2700 Phoenix Performance 100K Portfolio 2 Buck TV 2706 AF POOLER GEORGIA 1106 NSFit Chico 2 Buck TV Internet 2707 AF WHITEMARSH ISLAND 121 LIMITED 2 Min Miracle 2709 AF 50 BERWICK BLVD 123 MONEY LIMITED 2009 Family Fitness Spart 2711 FAST FIT BOOTCAMP ED 123HJEMMESIDE APS 2010 Family Fitness Plain 2834 FITNESS PREMIER LOWE 125-Bonner & Partners Fam 2-10 HBW WARRANTY OF CALI 2864 ECLIPSE FITNESS 1288 SlimSpa Diet 2-10 HOLDCO, INC. 2865 Family Fitness Stand 141 The Open Gym 2-10 HOME BUYERS WARRRANT 2CHECKOUT.COM 142B kit merchant 21ST CENTURY INS&FINANCE 300-Oxford Club 147 AF Mendota 2348 AF Alexandria 3012 AF NICHOLASVILLE 1486 Push 2 Crossfit 2369 Olympus 365 3026 Family Fitness Alpin 1496 CKO KICKBOXING 2382 Sequence Fitness PCB 303-Wall Street Daily 1535 KFIT BOOTCAMP 2389730 ONTARIO INC 3045 AF GALLATIN 1539 Family Fitness Norto 2390 Family Fitness Apple 304-Money Map Press 1540 Family Fitness Plain 24 Assistance CAN/US 3171 AF -

Annual Report 2005 J P M O R G a N C H a S E

JPMORGAN CHASE & CO. Annual Report 2005 JPMorgan Chase & Co. 2005 Annual Report JPMorgan Chase & Co. www.jpmorganchase.com JPMorgan Chase & Co. JPMorgan Chase & Co. (NYSE: JPM) is a leading global financial services firm with assets of $1.2 trillion and operations in more than 50 countries. The firm is a leader in investment banking, financial services Corporate headquarters Directors Direct deposit of dividends for consumers, small business and commercial banking, financial transaction processing, asset and wealth 270 Park Avenue To contact any of the Board members please For information about direct deposit of management, and private equity. A component of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, JPMorgan Chase New York, New York 10017-2070 mail correspondence to: dividends, please contact Mellon Investor serves millions of consumers in the United States and many of the world’s most prominent corporate, Telephone: 212-270-6000 JPMorgan Chase & Co. Services LLC. http://www.jpmorganchase.com Attention (Board member) institutional and government clients under its JPMorgan and Chase brands. Stockholder inquiries Office of the Secretary Principal subsidiaries 270 Park Avenue Contact Mellon Investor Services LLC: JPMorgan Chase Bank, New York, New York 10017-2070 National Association By telephone: Chase Bank USA, The corporate governance principles of Within the United States, Canada and National Association the board, the charters of the principal Puerto Rico: 1-800-758-4651 J.P. Morgan Securities Inc. board committees and other governance (toll free) information can be accessed by visiting From all other locations: JPMorgan has one of the largest client franchises in the world. Our clients include corporations, Annual report on Form 10-K www.jpmorganchase.com and clicking on 1-201-680-6578 (collect) institutional investors, hedge funds, governments and affluent individuals in more than 100 countries. -

The Retirement Plan Summary Plan Description Jpmorgan Chase

The Retirement Plan Summary Plan Description JPMorgan Chase January 1, 2019 This summary plan description applies only to employees who were hired before December 2, 2017 and have a cash balance account in the JPMorgan Chase Retirement Plan as of December 31, 2018 (and certain rehires after December 31, 2018). The Retirement Plan The JPMorgan Chase Retirement Plan (the “Plan” or Update: Your Summary Plan “Retirement Plan”) is fully paid for by JPMorgan Chase and Description for the JPMorgan Chase Retirement Plan provides a foundation for your retirement income. (Replaces the January 1, 2016 summary As discussed in greater detail below, the Plan is now plan description) “frozen” and closed to new entrants. Prior to the freeze, This document is your summary plan description of the JPMorgan Chase participation in the Retirement Plan was automatic once Retirement Plan. This summary plan description provides you with important you completed one year of total service. Your Retirement information required by the Employee Plan benefit is expressed as a cash balance benefit that Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) about the Retirement Plan. grows in a notional bookkeeping account over time through While ERISA does not require pay credits and interest credits. For each month you work at JPMorgan Chase to provide you with benefits, it does mandate that JPMorgan Chase while eligible for the Plan through JPMorgan Chase clearly communicate to December 31, 2019, the company will credit your account you how the Retirement Plan operates and what rights you have under the law regarding with a percentage of your Eligible Compensation — from Plan benefits. -

Annual Report Jpmorgan Chase &

JPMORGAN CHASE & CO. ANNUAL REPORT2006 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS As of or for the year ended December 31, (in millions, except per share, ratio and headcount data) 2006 2005 Reported basis (a) Total net revenue $ 61,437 $ 53,748 Provision for credit losses 3,270 3,483 Total noninterest expense 38,281 38,426 Income from continuing operations 13,649 8,254 Net income $ 14,444 $ 8,483 Per common share: Basic earnings per share Income from continuing operations $ 3.93 $ 2.36 Net income 4.16 2.43 Diluted earnings per share Income from continuing operations $ 3.82 $ 2.32 Net income 4.04 2.38 Cash dividends declared per share 1.36 1.36 Book value per share 33.45 30.71 Return on common equity Income from continuing operations 12% 8% Net income 13 8 Return on common equity (net of goodwill) Income from continuing operations 20% 13% Net income 22 14 Tier 1 capital ratio 8.7 8.5 Total capital ratio 12.3 12.0 Total assets $ 1,351,520 $1,198,942 Loans 483,127 419,148 Deposits 638,788 554,991 Total stockholders’ equity 115,790 107,211 Headcount 174,360 168,847 (a) Results are presented in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America. JPMorgan Chase & Co. (NYSE: JPM) is a leading global financial services firm with assets of $1.4 trillion and operations in more than 50 countries. The firm is a leader in investment banking, financial services for consumers, small business and commercial banking, financial transaction processing, asset management and private equity. -

COMMENT Jpmorgan Chase & Co. (NYSE: JPM)

INITIATION | COMMENT 125 WEEKS 22FEB08 - 09JUL10 Rel. S&P 500 HI-10OCT08 142.63 JULY 12, 2010 135.00 HI/LO DIFF -49.66% 120.00 105.00 CLOSE 111.01 JPMorgan Chase & Co. (NYSE: JPM) 90.00 75.00 LO-06MAR09 71.80 2008 2009 2010 FM A M J J A S O N D J F M A M J J A S O N D J F M A M J J Regulatory Smoke Clouding Underlying Value HI-03OCT08 50.63 48.00 HI/LO DIFF -70.45% 42.00 36.00 30.00 CLOSE 38.85 Outperform 24.00 Average Risk 18.00 Price Target: 45.00 LO-06MAR09 14.96 Price: 39.18 600000 Implied All-In Return: 15% Market Cap (MM): 155,897 400000 PEAK VOL.709186.9 Shares O/S (MM): 3,979.0 200000 VOLUME 152297.9 Dividend: 0.05 Yield: 0.1% BVPS: 39.38 P/BVPS: 1.0x Tangible BVPS: 26.40 Avg. Daily Volume (MM): 42.00 RBC Capital Markets Corp. ROE: 7.6% Float (MM): 133,194.0 Gerard Cassidy (Analyst) Institutional Ownership: 76% (207) 780-1554; [email protected] Priced as of market close, ET July 12, 2010. Jake Civiello (Associate) (207) 780-1554; [email protected] Initiating Coverage at Outperform with a $45 Price Target Investment Opinion FY Dec 2008A 2009A 2010E 2011E EPS (Op) - FD 0.83 2.52 3.12 4.58 • Initiating at Outperform: We are initiating coverage of JPMorgan Chase & P/E 47.2x 15.5x 12.6x 8.6x Co. -

Payments Powering Platforms Tracker™ JANUARY 2017

Payments Powering Platforms Tracker™ JANUARY 2017 Always Be ... Building a Better Platform? How mobile technology and Sixa lands $3.5M for Find the top providers in our platforms are transforming the developer-focused cloud inaugural Tracker Scorecard – construction industry. – p. 6 computer – p. 12 (News and p. 16 (Scorecard) (Feature Story) Trends) Payments Powering Platforms Tracker™ © 2017 PYMNTS.com all rights reserved Table of Contents PAGE What’s Inside We take a closer look at the quickly evolving platform space and how platform 03 providers are keeping their data and customers well secured. PAGE Feature Story Buildertrend Solutions Director Scott Siegert discusses how the company has had to shift constantly to keep up with new technology and changing client 06 demands in order to stay ahead. PAGE News and Trends 10 Read the latest news and headlines from around the space. PAGE Methodology | Top Ten Rankings Best of the bunch 14 Who’s on top and how they got there. PAGE Scorecard The results are in 16 See who the top providers are. PAGE About 24 Information on PYMNTS.com and WePay. Acknowledgment Sponsorship for the Payments Powering Platforms Tracker™ was provided by WePay. WePay has no editorial influence over the Tracker’s content. In addition, the methodology for Tracker supplier rankings was developed exclusively by the PYMNTS.com research and analytics team. The methodology, scoring and rankings are done exclusively by this team and without input or influence from the sponsoring organization. Payments Powering Platforms Tracker™ © 2017 PYMNTS.com all rights reserved January 2017 | 2 What’s Inside Software platforms are changing the way all kinds Countless entrepreneurs and everyday people use of companies and organizations, from construction these platforms for a wide variety of applications.