Ecological and Life History Factors Influence Habitat and Tool Use in Wild Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops Sp.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Spirocamallanus) Monotaxis (Nematoda: Camallanidae) from Marine Fishes Off New Caledonia

©2011 Parasitological Institute of SAS, Košice DOI 10.2478/s11687-011-0008-4 HELMINTHOLOGIA, 48, 1: 41 – 50, 2011 New data on the morphology of Procamallanus (Procamallanus) annulatus and Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) monotaxis (Nematoda: Camallanidae) from marine fishes off New Caledonia F. MORAVEC1, J.-L. JUSTINE2,3 1Institute of Parasitology, Biology Centre of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Branišovská 31, 370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic, E-mail: [email protected]; 2UMR 7138 Systématique, Adaptation, Évolution, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Case postale 52, 57, rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris cedex 05, France; 3Aquarium des Lagons, B. P. 8185, 98807 Nouméa, Nouvelle-Calédonie Summary ........ Two little-known nematode species of the family Camalla- remains insufficiently known. Only three nominal species nidae, intestinal parasites of marine perciform fishes, are of adult camallanids have so far been reported from marine reported from off New Caledonia: Procamallanus (Pro- fishes in New Caledonian waters: Camallanus carangis camallanus) annulatus Yamaguti, 1955 from the golden- Olsen, 1954 from Nemipterus furcosus (Valenciennes) lined spinefoot Siganus lineatus (Valenciennes) (Sigani- (Nemipteridae), Parupeneus ciliatus (Lacépède) and dae) and Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) monotaxis Upeneus vittatus (Forsskål) (both Mullidae); Procamal- (Olsen, 1952) from the longspine emperor Lethrinus lanus (Spirocamallanus) guttatusi (Andrade-Salas, Pineda- genivittatus Valenciennes and the slender emperor Lethri- López -

Pacific Plate Biogeography, with Special Reference to Shorefishes

Pacific Plate Biogeography, with Special Reference to Shorefishes VICTOR G. SPRINGER m SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY • NUMBER 367 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoo/ogy Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world cf science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

No Change in the Recent Lunar Impact Flux Required Based On

Geophysical Research Letters RESEARCH LETTER No Change in the Recent Lunar Impact Flux Required Based 10.1029/2018GL077254 on Modeling of Impact Glass Spherule Age Distributions Key Points: • An excess of young lunar impact glass Ya-Huei Huang1 , David A. Minton1, Nicolle E. B. Zellner2 , Masatoshi Hirabayashi3 , spherules <500 Ma likely results from 4 5 limited sampling depths where lunar James E. Richardson , and Caleb I. Fassett soils were collected • Sampling biases can explain the 1Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Science, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2Department of excess of young spherules, rather than Physics, Albion College, Albion, MI, USA, 3Department of Aerospace Engineering, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA, a significant change in the impact flux 4Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, AZ, USA, 5NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, AL, USA in the last 500 Ma • Using lunar impact glass spherule ages to constrain the impact flux may 40 39 be less biased if collected beyond the Abstract The distributions of Ar/ Ar-derived ages of impact glass spherules in lunar regolith uppermost lunar surface samples show an excess at <500 Ma relative to older ages. It has not been well understood whether this excess of young ages reflects an increase in the recent lunar impact flux or is due to a bias in the samples. Supporting Information: We developed a model to simulate the production, transport, destruction, and sampling of lunar glass • Supporting Information S1 spherules. A modeled bias is seen when either (1) the simulated sampling depth is 10 cm, consistent with the typical depth from which Apollo soil samples were taken, or (2) when glass occurrence in the ejecta is > Correspondence to: limited to 10 crater radii from the crater, consistent with terrestrial microtektite observations. -

BEYOND Alumni Share How the Gordon and Judy Dutile Honors Program Has Prepared Them for a Lifetime of Excellence

A B O V E &BEYOND Alumni share how the Gordon and Judy Dutile Honors Program has prepared them for a lifetime of excellence INSIDE: 2015 PRESIDENT’S REPORT PB SBUlife Winter 2015 www.SBUniv.edu SBUlife 1 >> Be Social Read what students are sharing about SBU. sbu is the best; they brought We had a FANTASTIC visit day to- puppies to the union for us to play day with 90+ on campus! Thanks with #sbuniv for making the time to come! (via @elizaburris on Instagram) #futurebearcats #SBUniv @ SBU_Kim Awesome job @SBUbearcatsWBB!! We are so proud of you girls!! Great win!! #bearcatroar #SBUniv @Dewey_Dogger Love this university. Being sur- rounded by so many people who have a deep desire to serve Jesus is truly incredible. #SBUniv @sward2013 In honor of finals and first semester being over, #tbt to when we first became a family. #woodythird #woodygott #sbuniv (via @mary_rose_18 on Instagram) Good morning, SBU. #sbuniv #jantermsnotsobad #midwestisbest (via @courtney_kliment on Instagram) Check out “The Hub” – Southwest Baptist University’s social media mash-up site showcasing what people are saying about SBU online. Go to social.SBUniv.edu to see Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and news release postings all in one place. And be sure to use #SBUniv when you post about SBU on social media and you may see your post featured on “The Hub” as well! Be social with SBU on Twitter, Facebook, 2 SBUlife Google+ and Instagram. #SBUniv Winter 2015 www.SBUniv.edu SBUlife 3 SBUlife Magazine of Southwest Baptist University Winter 2016 10th Anniversary of the Gordon and Judy Dutile Honors Program 2 5 Questions with Diana Gallamore 4 Guess Who? 22 SBU News 23 Keeping in Touch 24 Volume 101 Issue 1 ADDRESS CHANGE SBUlife highlights the University’s mission: to be USPS 507-500 POSTMASTER: Send address changes to a Christ-centered, caring academic community SBU 1600 University Avenue, preparing students to be servant leaders in a global PRESIDENT Bolivar, MO 65613-2597 society. -

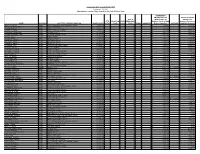

Public Act 097-0256 2018-2019.Pdf

Community Unit School District 300 Public Act 097-256 Administrator Teacher Salary Report for 2018-2019 School Year RETIREMENT ENHANCEMENTS OTHER BENEFITS SICK & (Board Paid TRS (Board Paid FTE VACATION FLEX PERSONAL Employee Portion, HRA Insurance Premiums, NAME POSITION JOB TITLE - PRIMARY POSITION BASE SALARY TOTAL DAYS DAYS DAYS BONUS ANNUITIES Retiree Deposits) MILEAGE HSA&HRA Deposits) ABOY, CRISTINA LEAD ELEM Kindergarten Dual Language Teacher $ 70,301.02 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,950.08 $ 5,723.59 ABRAHAM, CATHERINE LEAD Speech Pathologist $ 57,672.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,285.39 $ 33.60 ADAME, SHILOH LEAD MS Language Arts Teacher $ 65,022.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,672.24 $ 13,263.17 ADAMS, BELINDA LEAD Behavior Disorder Teacher $ 70,301.02 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,950.08 $ 19,970.00 ADAMSON, STEPHANIE LEAD MS Math Teacher $ 52,852.00 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,031.71 $ 19,874.36 ADAMS-WHITSON, VICKI LEAD Cross Catergorical Teacher $ 51,817.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 2,977.23 $ 6,079.03 ADKINS, HOLLY LEAD Media Teacher $ 44,292.00 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 2,581.18 $ 33.60 ADLER, LEIGH LEAD School Counselor $ 89,264.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 4,948.14 $ 19,962.08 AGARWAL, MEENU LEAD MS ESL Teacher $ 58,802.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,344.87 $ 192.72 AGENEAU, CARIE LEAD HS French Teacher $ 51,875.02 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 2,980.29 $ 5,763.19 AGENEAU, EMMA LEAD HS Spanish Teacher $ 50,859.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 2,926.81 $ 5,763.19 AGENLIAN, JULI LEAD ELEM Second Grade Teacher $ 58,892.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,349.60 $ 19,802.96 AGUILAR, NICOLE LEAD MS ESL Teacher $ 60,070.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,411.60 $ 13,263.17 AGUINAGA, -

Magnetized Impact Craters

Icarus xxx (2011) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Predicted and observed magnetic signatures of martian (de)magnetized impact craters ⇑ Benoit Langlais a, , Erwan Thébault b a CNRS UMR 6112, Université de Nantes, Laboratoire de Planétologie et Géodynamique, 2 Rue de la Houssinière, F-44000 Nantes, France b CNRS UMR 7154, Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, Équipe de Géomagnétisme, 1 Rue Cuvier, F-75005 Paris, France article info abstract Article history: The current morphology of the martian lithospheric magnetic field results from magnetization and Received 3 May 2010 demagnetization processes, both of which shaped the planet. The largest martian impact craters, Hellas, Revised 6 January 2011 Argyre, Isidis and Utopia, are not associated with intense magnetic fields at spacecraft altitude. This is Accepted 6 January 2011 usually interpreted as locally non- or de-magnetized areas, as large impactors may have reset the mag- Available online xxxx netization of the pre-impact material. We study the effects of impacts on the magnetic field. First, a care- ful analysis is performed to compute the impact demagnetization effects. We assume that the pre-impact Keywords: lithosphere acquired its magnetization while cooling in the presence of a global, centered and mainly Mars, Surface dipolar magnetic field, and that the subsequent demagnetization is restricted to the excavation area cre- Mars, Interior Impact processes ated by large craters, between 50- and 500-km diameter. Depth-to-diameter ratio of the transient craters Magnetic fields is set to 0.1, consistent with observed telluric bodies. Associated magnetic field is computed between 100- and 500-km altitude. -

Reef Fishes of the Bird's Head Peninsula, West

Check List 5(3): 587–628, 2009. ISSN: 1809-127X LISTS OF SPECIES Reef fishes of the Bird’s Head Peninsula, West Papua, Indonesia Gerald R. Allen 1 Mark V. Erdmann 2 1 Department of Aquatic Zoology, Western Australian Museum. Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Perth, Western Australia 6986. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Conservation International Indonesia Marine Program. Jl. Dr. Muwardi No. 17, Renon, Denpasar 80235 Indonesia. Abstract A checklist of shallow (to 60 m depth) reef fishes is provided for the Bird’s Head Peninsula region of West Papua, Indonesia. The area, which occupies the extreme western end of New Guinea, contains the world’s most diverse assemblage of coral reef fishes. The current checklist, which includes both historical records and recent survey results, includes 1,511 species in 451 genera and 111 families. Respective species totals for the three main coral reef areas – Raja Ampat Islands, Fakfak-Kaimana coast, and Cenderawasih Bay – are 1320, 995, and 877. In addition to its extraordinary species diversity, the region exhibits a remarkable level of endemism considering its relatively small area. A total of 26 species in 14 families are currently considered to be confined to the region. Introduction and finally a complex geologic past highlighted The region consisting of eastern Indonesia, East by shifting island arcs, oceanic plate collisions, Timor, Sabah, Philippines, Papua New Guinea, and widely fluctuating sea levels (Polhemus and the Solomon Islands is the global centre of 2007). reef fish diversity (Allen 2008). Approximately 2,460 species or 60 percent of the entire reef fish The Bird’s Head Peninsula and surrounding fauna of the Indo-West Pacific inhabits this waters has attracted the attention of naturalists and region, which is commonly referred to as the scientists ever since it was first visited by Coral Triangle (CT). -

Facility Facility Address Visn Name Title Telephone # Email

Prosthetics and Sensory Aids Service -- National Staff Directory Facility TELEPHONE FACILITY FACILITY ADDRESS VISN NAME TITLE EMAIL FAX# Number # Birmingham, Alabama VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, POSEY, Teresa Chief of Prosthetics (205) 933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x6942 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, McCULLOUGH, Cynthia Administrative Assistant (205) 933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x6040 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, WILLIS, Janice Program Support Assistant (205) 933-8101 Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 x4508 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, GUYTON, Phyllis Purchasing Agent (205) 933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x3262 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, HARDING, Rachel Contract Specialist (205) 933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x6091 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, LAWSON, Shelia Purchasing Agent (205) 933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x5359 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, McRAE, Marcia Lead Purchasing Agent (205) 933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x6940 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, NGU, Tina Purchasing Agent (205) 933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x5435 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, O'REE, Ollie Purchasing Agent (205) 933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x6590 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, CHAPMAN, Davida Purchasing Agent (205)933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x5088 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, WILLIAMS, Seth J. -

Monitoring Functional Groups of Herbivorous Reef Fishes As Indicators of Coral Reef Resilience a Practical Guide for Coral Reef Managers in the Asia Pacifi C Region

Monitoring Functional Groups of Herbivorous Reef Fishes as Indicators of Coral Reef Resilience A practical guide for coral reef managers in the Asia Pacifi c Region Alison L. Green and David R. Bellwood IUCN RESILIENCE SCIENCE GROUP WORKING PAPER SERIES - NO 7 IUCN Global Marine Programme Founded in 1958, IUCN (the International Union for the Conservation of Nature) brings together states, government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organizations in a unique world partnership: over 100 members in all, spread across some 140 countries. As a Union, IUCN seeks to influence, encourage and assist societies throughout the world to conserve the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustainable. The IUCN Global Marine Programme provides vital linkages for the Union and its members to all the IUCN activities that deal with marine issues, including projects and initiatives of the Regional offices and the six IUCN Commissions. The IUCN Global Marine Programme works on issues such as integrated coastal and marine management, fisheries, marine protected areas, large marine ecosystems, coral reefs, marine invasives and protection of high and deep seas. The Nature Conservancy The mission of The Nature Conservancy is to preserve the plants, animals and natural communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters they need to survive. The Conservancy launched the Global Marine Initiative in 2002 to protect and restore the most resilient examples of ocean and coastal ecosystems in ways that benefit marine life, local communities and economies. -

![Arxiv:1612.06398V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 19 Dec 2016 Thousands of Objects Per System (E.G., Battaglia Et Al](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9055/arxiv-1612-06398v1-astro-ph-ga-19-dec-2016-thousands-of-objects-per-system-e-g-battaglia-et-al-959055.webp)

Arxiv:1612.06398V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 19 Dec 2016 Thousands of Objects Per System (E.G., Battaglia Et Al

Draft version October 1, 2018 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 5/2/11 CRATER 2: AN EXTREMELY COLD DARK MATTER HALO Nelson Caldwell1, Matthew G. Walker2, Mario Mateo3, Edward W. Olszewski4, Sergey Koposov5, Vasily Belokurov5, Gabriel Torrealba5, Alex Geringer-Sameth2 and Christian I. Johnson1 Draft version October 1, 2018 ABSTRACT We present results from MMT/Hectochelle spectroscopy of 390 red giant candidate stars along the line of sight to the recently-discovered Galactic satellite Crater 2. Modelling the joint distribution of stellar positions, velocities and metallicities as a mixture of Crater 2 and Galactic foreground populations, we identify 62 members of Crater 2, for which we resolve line-of-sight velocity dispersion +0:3 1 ∼ +0:4 1 σvlos =2:7 0:3 km s− about mean velocity of vlos =87:5 0:4 km s− (solar rest frame). We also − +0:04h i − +0:1 resolve a metallicity dispersion σ[Fe=H]=0:22 0:03 dex about a mean of [Fe/H] = 1:98 0:1 dex that is 0:28 0:14 dex poorer than is estimated− from photometry. Despiteh Crateri − 2's relatively− large ± size (projected halflight radius Rh 1 kpc) and intermediate luminosity (MV 8), its velocity dispersion is the coldest that has been∼ resolved for any dwarf galaxy. These properties∼ − make Crater 2 the most extreme low-density outlier in dynamical as well as structural scaling relations among the Milky Way's dwarf spheroidals. Even so, under assumptions of dynamical equilibrium and negligible contamination by unresolved binary stars, the observed velocity distribution implies a gravitationally +1:2 6 +15 dominant dark matter halo, with dynamical mass 4:4 0:9 10 M and mass-to-light ratio 53 11 − × +0:5 − M =LV; enclosed within a radius of 1 kpc, where the equivalent circular velocity is 4:3 0:5 km 1 ∼ − s− . -

Pnas11741toc 3..8

October 13, 2020 u vol. 117 u no. 41 From the Cover 25609 Evolutionary history of pteropods 25327 Burn markers from Chicxulub crater 25378 Rapid warming and reef fish mortality 25601 Air pollution and mortality burden 25722 CRISPR-based diagnostic test for malaria Contents THIS WEEK IN PNAS—This week’s research highlights Cover image: Pictured are several 25183 In This Issue species of pteropods. Using phylogenomic data and fossil evidence, — Katja T. C. A. Peijnenburg et al. INNER WORKINGS An over-the-shoulder look at scientists at work reconstructed the evolutionary history of 25186 Researchers peek into chromosomes’ 3D structure in unprecedented detail pteropods to evaluate the mollusks’ Amber Dance responses to past fluctuations in Earth’s carbon cycle. All major pteropod groups QNAS—Interviews with leading scientific researchers and newsmakers diverged in the Cretaceous, suggesting resilience to ensuing periods of 25190 QnAs with J. Michael Kosterlitz increased atmospheric carbon and Farooq Ahmed ocean acidification. However, it is unlikely that pteropods ever PROFILE—The life and work of NAS members experienced carbon release rates of the current magnitude. See the article by 25192 Profile of Subra Suresh Peijnenburg et al. on pages 25609– Sandeep Ravindran 25617. Image credit: Katja T. C. A. Peijnenburg and Erica Goetze. COMMENTARIES 25195 One model to rule them all in network science? Roger Guimera` See companion article on page 23393 in issue 38 of volume 117 25198 Cis-regulatory units of grass genomes identified by their DNA methylation Peng Liu and R. Keith Slotkin See companion article on page 23991 in issue 38 of volume 117 LETTERS 25200 Not all trauma is the same Qin Xiang Ng, Donovan Yutong Lim, and Kuan Tsee Chee 25201 Reply to Ng et al.: Not all trauma is the same, but lessons can be drawn from commonalities Ethan J. -

Benthic Habitats and Biodiversity of Dampier and Montebello Marine

CSIRO OCEANS & ATMOSPHERE Benthic habitats and biodiversity of the Dampier and Montebello Australian Marine Parks Edited by: John Keesing, CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere Research March 2019 ISBN 978-1-4863-1225-2 Print 978-1-4863-1226-9 On-line Contributors The following people contributed to this study. Affiliation is CSIRO unless otherwise stated. WAM = Western Australia Museum, MV = Museum of Victoria, DPIRD = Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Study design and operational execution: John Keesing, Nick Mortimer, Stephen Newman (DPIRD), Roland Pitcher, Keith Sainsbury (SainsSolutions), Joanna Strzelecki, Corey Wakefield (DPIRD), John Wakeford (Fishing Untangled), Alan Williams Field work: Belinda Alvarez, Dion Boddington (DPIRD), Monika Bryce, Susan Cheers, Brett Chrisafulli (DPIRD), Frances Cooke, Frank Coman, Christopher Dowling (DPIRD), Gary Fry, Cristiano Giordani (Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia), Alastair Graham, Mark Green, Qingxi Han (Ningbo University, China), John Keesing, Peter Karuso (Macquarie University), Matt Lansdell, Maylene Loo, Hector Lozano‐Montes, Huabin Mao (Chinese Academy of Sciences), Margaret Miller, Nick Mortimer, James McLaughlin, Amy Nau, Kate Naughton (MV), Tracee Nguyen, Camilla Novaglio, John Pogonoski, Keith Sainsbury (SainsSolutions), Craig Skepper (DPIRD), Joanna Strzelecki, Tonya Van Der Velde, Alan Williams Taxonomy and contributions to Chapter 4: Belinda Alvarez, Sharon Appleyard, Monika Bryce, Alastair Graham, Qingxi Han (Ningbo University, China), Glad Hansen (WAM),