Arxiv:1612.06398V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 19 Dec 2016 Thousands of Objects Per System (E.G., Battaglia Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Change in the Recent Lunar Impact Flux Required Based On

Geophysical Research Letters RESEARCH LETTER No Change in the Recent Lunar Impact Flux Required Based 10.1029/2018GL077254 on Modeling of Impact Glass Spherule Age Distributions Key Points: • An excess of young lunar impact glass Ya-Huei Huang1 , David A. Minton1, Nicolle E. B. Zellner2 , Masatoshi Hirabayashi3 , spherules <500 Ma likely results from 4 5 limited sampling depths where lunar James E. Richardson , and Caleb I. Fassett soils were collected • Sampling biases can explain the 1Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Science, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2Department of excess of young spherules, rather than Physics, Albion College, Albion, MI, USA, 3Department of Aerospace Engineering, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA, a significant change in the impact flux 4Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, AZ, USA, 5NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, AL, USA in the last 500 Ma • Using lunar impact glass spherule ages to constrain the impact flux may 40 39 be less biased if collected beyond the Abstract The distributions of Ar/ Ar-derived ages of impact glass spherules in lunar regolith uppermost lunar surface samples show an excess at <500 Ma relative to older ages. It has not been well understood whether this excess of young ages reflects an increase in the recent lunar impact flux or is due to a bias in the samples. Supporting Information: We developed a model to simulate the production, transport, destruction, and sampling of lunar glass • Supporting Information S1 spherules. A modeled bias is seen when either (1) the simulated sampling depth is 10 cm, consistent with the typical depth from which Apollo soil samples were taken, or (2) when glass occurrence in the ejecta is > Correspondence to: limited to 10 crater radii from the crater, consistent with terrestrial microtektite observations. -

BEYOND Alumni Share How the Gordon and Judy Dutile Honors Program Has Prepared Them for a Lifetime of Excellence

A B O V E &BEYOND Alumni share how the Gordon and Judy Dutile Honors Program has prepared them for a lifetime of excellence INSIDE: 2015 PRESIDENT’S REPORT PB SBUlife Winter 2015 www.SBUniv.edu SBUlife 1 >> Be Social Read what students are sharing about SBU. sbu is the best; they brought We had a FANTASTIC visit day to- puppies to the union for us to play day with 90+ on campus! Thanks with #sbuniv for making the time to come! (via @elizaburris on Instagram) #futurebearcats #SBUniv @ SBU_Kim Awesome job @SBUbearcatsWBB!! We are so proud of you girls!! Great win!! #bearcatroar #SBUniv @Dewey_Dogger Love this university. Being sur- rounded by so many people who have a deep desire to serve Jesus is truly incredible. #SBUniv @sward2013 In honor of finals and first semester being over, #tbt to when we first became a family. #woodythird #woodygott #sbuniv (via @mary_rose_18 on Instagram) Good morning, SBU. #sbuniv #jantermsnotsobad #midwestisbest (via @courtney_kliment on Instagram) Check out “The Hub” – Southwest Baptist University’s social media mash-up site showcasing what people are saying about SBU online. Go to social.SBUniv.edu to see Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and news release postings all in one place. And be sure to use #SBUniv when you post about SBU on social media and you may see your post featured on “The Hub” as well! Be social with SBU on Twitter, Facebook, 2 SBUlife Google+ and Instagram. #SBUniv Winter 2015 www.SBUniv.edu SBUlife 3 SBUlife Magazine of Southwest Baptist University Winter 2016 10th Anniversary of the Gordon and Judy Dutile Honors Program 2 5 Questions with Diana Gallamore 4 Guess Who? 22 SBU News 23 Keeping in Touch 24 Volume 101 Issue 1 ADDRESS CHANGE SBUlife highlights the University’s mission: to be USPS 507-500 POSTMASTER: Send address changes to a Christ-centered, caring academic community SBU 1600 University Avenue, preparing students to be servant leaders in a global PRESIDENT Bolivar, MO 65613-2597 society. -

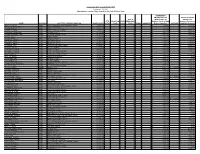

Public Act 097-0256 2018-2019.Pdf

Community Unit School District 300 Public Act 097-256 Administrator Teacher Salary Report for 2018-2019 School Year RETIREMENT ENHANCEMENTS OTHER BENEFITS SICK & (Board Paid TRS (Board Paid FTE VACATION FLEX PERSONAL Employee Portion, HRA Insurance Premiums, NAME POSITION JOB TITLE - PRIMARY POSITION BASE SALARY TOTAL DAYS DAYS DAYS BONUS ANNUITIES Retiree Deposits) MILEAGE HSA&HRA Deposits) ABOY, CRISTINA LEAD ELEM Kindergarten Dual Language Teacher $ 70,301.02 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,950.08 $ 5,723.59 ABRAHAM, CATHERINE LEAD Speech Pathologist $ 57,672.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,285.39 $ 33.60 ADAME, SHILOH LEAD MS Language Arts Teacher $ 65,022.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,672.24 $ 13,263.17 ADAMS, BELINDA LEAD Behavior Disorder Teacher $ 70,301.02 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,950.08 $ 19,970.00 ADAMSON, STEPHANIE LEAD MS Math Teacher $ 52,852.00 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,031.71 $ 19,874.36 ADAMS-WHITSON, VICKI LEAD Cross Catergorical Teacher $ 51,817.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 2,977.23 $ 6,079.03 ADKINS, HOLLY LEAD Media Teacher $ 44,292.00 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 2,581.18 $ 33.60 ADLER, LEIGH LEAD School Counselor $ 89,264.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 4,948.14 $ 19,962.08 AGARWAL, MEENU LEAD MS ESL Teacher $ 58,802.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,344.87 $ 192.72 AGENEAU, CARIE LEAD HS French Teacher $ 51,875.02 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 2,980.29 $ 5,763.19 AGENEAU, EMMA LEAD HS Spanish Teacher $ 50,859.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 2,926.81 $ 5,763.19 AGENLIAN, JULI LEAD ELEM Second Grade Teacher $ 58,892.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,349.60 $ 19,802.96 AGUILAR, NICOLE LEAD MS ESL Teacher $ 60,070.01 1 0 0 14 0 0 $ 3,411.60 $ 13,263.17 AGUINAGA, -

Magnetized Impact Craters

Icarus xxx (2011) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Predicted and observed magnetic signatures of martian (de)magnetized impact craters ⇑ Benoit Langlais a, , Erwan Thébault b a CNRS UMR 6112, Université de Nantes, Laboratoire de Planétologie et Géodynamique, 2 Rue de la Houssinière, F-44000 Nantes, France b CNRS UMR 7154, Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, Équipe de Géomagnétisme, 1 Rue Cuvier, F-75005 Paris, France article info abstract Article history: The current morphology of the martian lithospheric magnetic field results from magnetization and Received 3 May 2010 demagnetization processes, both of which shaped the planet. The largest martian impact craters, Hellas, Revised 6 January 2011 Argyre, Isidis and Utopia, are not associated with intense magnetic fields at spacecraft altitude. This is Accepted 6 January 2011 usually interpreted as locally non- or de-magnetized areas, as large impactors may have reset the mag- Available online xxxx netization of the pre-impact material. We study the effects of impacts on the magnetic field. First, a care- ful analysis is performed to compute the impact demagnetization effects. We assume that the pre-impact Keywords: lithosphere acquired its magnetization while cooling in the presence of a global, centered and mainly Mars, Surface dipolar magnetic field, and that the subsequent demagnetization is restricted to the excavation area cre- Mars, Interior Impact processes ated by large craters, between 50- and 500-km diameter. Depth-to-diameter ratio of the transient craters Magnetic fields is set to 0.1, consistent with observed telluric bodies. Associated magnetic field is computed between 100- and 500-km altitude. -

Facility Facility Address Visn Name Title Telephone # Email

Prosthetics and Sensory Aids Service -- National Staff Directory Facility TELEPHONE FACILITY FACILITY ADDRESS VISN NAME TITLE EMAIL FAX# Number # Birmingham, Alabama VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, POSEY, Teresa Chief of Prosthetics (205) 933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x6942 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, McCULLOUGH, Cynthia Administrative Assistant (205) 933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x6040 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, WILLIS, Janice Program Support Assistant (205) 933-8101 Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 x4508 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, GUYTON, Phyllis Purchasing Agent (205) 933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x3262 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, HARDING, Rachel Contract Specialist (205) 933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x6091 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, LAWSON, Shelia Purchasing Agent (205) 933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x5359 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, McRAE, Marcia Lead Purchasing Agent (205) 933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x6940 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, NGU, Tina Purchasing Agent (205) 933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x5435 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, O'REE, Ollie Purchasing Agent (205) 933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x6590 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, CHAPMAN, Davida Purchasing Agent (205)933- Alabama 35233 521 VISN 7 [email protected] (205) 558-4811 8101x5088 VAMC, Birmingham, Alabama 700 South 19th Street, Birmingham, WILLIAMS, Seth J. -

Pnas11741toc 3..8

October 13, 2020 u vol. 117 u no. 41 From the Cover 25609 Evolutionary history of pteropods 25327 Burn markers from Chicxulub crater 25378 Rapid warming and reef fish mortality 25601 Air pollution and mortality burden 25722 CRISPR-based diagnostic test for malaria Contents THIS WEEK IN PNAS—This week’s research highlights Cover image: Pictured are several 25183 In This Issue species of pteropods. Using phylogenomic data and fossil evidence, — Katja T. C. A. Peijnenburg et al. INNER WORKINGS An over-the-shoulder look at scientists at work reconstructed the evolutionary history of 25186 Researchers peek into chromosomes’ 3D structure in unprecedented detail pteropods to evaluate the mollusks’ Amber Dance responses to past fluctuations in Earth’s carbon cycle. All major pteropod groups QNAS—Interviews with leading scientific researchers and newsmakers diverged in the Cretaceous, suggesting resilience to ensuing periods of 25190 QnAs with J. Michael Kosterlitz increased atmospheric carbon and Farooq Ahmed ocean acidification. However, it is unlikely that pteropods ever PROFILE—The life and work of NAS members experienced carbon release rates of the current magnitude. See the article by 25192 Profile of Subra Suresh Peijnenburg et al. on pages 25609– Sandeep Ravindran 25617. Image credit: Katja T. C. A. Peijnenburg and Erica Goetze. COMMENTARIES 25195 One model to rule them all in network science? Roger Guimera` See companion article on page 23393 in issue 38 of volume 117 25198 Cis-regulatory units of grass genomes identified by their DNA methylation Peng Liu and R. Keith Slotkin See companion article on page 23991 in issue 38 of volume 117 LETTERS 25200 Not all trauma is the same Qin Xiang Ng, Donovan Yutong Lim, and Kuan Tsee Chee 25201 Reply to Ng et al.: Not all trauma is the same, but lessons can be drawn from commonalities Ethan J. -

2021 PISD Attendancezone M

G Paradise Valley Dr l e Ola Ln Whisenant Dr Lake Highlands Dr Harvest Run Dr Loma Alta Dr n Lone Star Ct 1 Miners Creek Rd 2 3 Robincreek Ln 4 5 W 6 R S 7 8 9 10 11 12 Halyard Dr a J A e o r g u Rivercrest Blvd O D s s Cool Springs Dr n C i n D Royal Troon Dr e n g Dr l t r Rivercrest Blvd r a Whitney Ct r c Moonlight T o a Hagen Dr l Dr D Fannin Ct t c e R C e R d u Blondy Jhune Trl y L r w m h Dr Stinson Dr Barley Plac D io D Fieldstone Dr l Rd Patagonian Pl w o r w P n en i e D a e l o i i l Autumn Lake Dr a l Warren Pkwy v a N Crossing Dr rv i f e n be idg Hunters l im R Frosted Green Ln L C Village Way T l w t M i h k n r r c e r r r c n e e r P n a Creek Ct D b e k d m w S l e h n i y L p t i u D 1 Rattle Run Dr k T L o r e M Burnet Dr f W r Daisy Dr r r Citrus Way G d Trl Timberbend r Austin Dr D o Artemis Ct o o a e e d y ac Macrocarpa Rd dl t Anns D d e Est r ak t e C W e Dr Legacy w onste Pebblebrook Dr d e o r C B Savann g r a Heather Glen Dr r ll r r R s a v D C d D D a i Hillcrest Rd a t Saint Mary Dr l h o o Braxton Ln D r w p b o i Wills Point Dr Oakland Hills Dr L r o Lake Ridge Dr ri k t Skyvie u 316 h R a i L C Way r L N White Porch Rd Dr y n O Knott Ct e s Rid Lime Cv i d n r g o e e d Katrina Path Aransas Dr Duval Dr n L k d Vidalia Ln Temp t s Co e Cir Citrus Way b t o e R ra D W M c ws i a r N Malone Rd R e W e n re t Kingswoo Blo e Windsor Rdg i e D r D t fo n o ndy Jhun B Dr Shallowater r N Watters Rd S l r til ra k Shadetree Ln s PLANO y L o r B z apsta R w a n Haystack Dr C n e d o Cutter Ln d w D Cedardale -

Ecological and Life History Factors Influence Habitat and Tool Use in Wild Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops Sp.)

ECOLOGICAL AND LIFE HISTORY FACTORS INFLUENCE HABITAT AND TOOL USE IN WILD BOTTLENOSE DOLPHINS (TURSIOPS SP.) A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biology By Eric Michael Patterson, B.S. Washington, DC December 7, 2012 Copyright 2011 by Eric Michael Patterson All Rights Reserved ii ECOLOGICAL AND LIFE HISTORY FACTORS INFLUENCE HABITAT AND TOOL USE IN WILD BOTTLENOSE DOLPHINS (TURSIOPS SP.) Eric Michael Patterson, B.S. Thesis Advisor: Janet Mann, Ph.D. ABSTRACT While it has long been known that individual animals behave quite distinctively from other conspecifics, only recently has this intraspecific behavioral variation itself been the subject of investigation rather than a nuisance in statistical analyses. As research amounts, it is becoming ever more apparent that the ecology of individuals can have real and measurable biological consequences. Previous studies have documented pronounced inter-individual variation in foraging behaviors in Shark Bay wild bottlenose dolphins, which often coincide with individual specialization. In this dissertation I examine how individuals’ phenotypic characteristics relate to their foraging behavior, habitat use, and ranging. In Chapter 1 I explore habitat and ranging for adult male and female bottlenose dolphins. Dolphins show marked intraspecific variation in both habitat use and ranging, which partially relates to foraging tactic, sex, and season. However, some variation cannot be explained by any obvious phenotypic or ecological factors, highlighting the importance of individual level analyses, especially for conservation and management. In Chapter 2 I examine the underlying basis of one foraging tactic involving tool use: sponge foraging. -

![Arxiv:2007.05011V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 17 Aug 2020 Laboration Et Al](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7525/arxiv-2007-05011v2-astro-ph-ga-17-aug-2020-laboration-et-al-1607525.webp)

Arxiv:2007.05011V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 17 Aug 2020 Laboration Et Al

Draft version August 19, 2020 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX63 Revised and new proper motions for confirmed and candidate Milky Way dwarf galaxies Alan W. McConnachie1 and Kim A. Venn2 1NRC Herzberg Astronomy and Astrophysics, 5071 West Saanich Road, Victoria, B.C., Canada, V9E 2E7 2Physics & Astronomy Department, University of Victoria, 3800 Finnerty Rd, Victoria, B.C., Canada, V8P 5C2 ABSTRACT A new derivation of systemic proper motions of Milky Way satellites is presented, and applied to 59 confirmed or candidate dwarf galaxy satellites using Gaia Data Release 2. This constitutes all known Milky Way dwarf galaxies (and likely candidates) as of May 2020 except the Magellanic Clouds, the Canis Major and Hydra 1 stellar overdensities, and the tidally disrupting Bootes III and Sagittarius dwarf galaxies. We derive systemic proper motions for the first time for Indus 1, DES J0225+0304, Cetus 2, Pictor 2 and Leo T, but note that the latter three rely on photometry that is of poorer quality than for the rest of the sample. We cannot resolve a signal for Bootes 4, Cetus 3, Indus 2, Pegasus 3, or Virgo 1. Our method is inspired by the maximum likelihood approach of Pace & Li(2019) and examines simultaneously the spatial, color-magnitude, and proper motion distribution of sources. Systemic proper motions are derived without the need to identify confirmed radial velocity members, although the proper motions of these stars, where available, are incorporated into the analysis through a prior on the model. The associated uncertainties on the systemic proper motions are on average a factor of ∼ 1:4 smaller than existing literature values. -

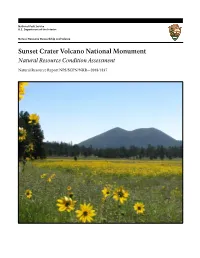

Natural Resource Condition Assessment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument Natural Resource Condition Assessment Natural Resource Report NPS/SCPN/NRR—2018/1837 ON THIS PAGE Desert globemallow. Photo Credit: NPS ON THE COVER A view of yellow sunflowers with Sunset Crater Volcano in the background. Photo Credit: NPS Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument Natural Resource Condition Assessment Natural Resource Report NPS/SCPN/NRR—2018/1837 Author Name(s) Lisa Baril1, Patricia Valentine-Darby1, Kimberly Struthers1, Paul Whitefield2 , Kirk Anderson3, Mark Brunson1 1Utah State University Department of Environment and Society Logan, Utah 2National Park Service Flagstaff Area National Monuments Flagstaff, Arizona 3Museum of Northern Arizona Flagstaff, Arizona Editing and Design Kimberly Struthers1 December 2018 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15445-2 — Mercury Edited by Sean C

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15445-2 — Mercury Edited by Sean C. Solomon , Larry R. Nittler , Brian J. Anderson Index More Information INDEX 253 Mathilde, 196 BepiColombo, 46, 109, 134, 136, 138, 279, 314, 315, 366, 403, 463, 2P/Encke, 392 487, 488, 535, 544, 546, 547, 548–562, 563, 564, 565 4 Vesta, 195, 196, 350 BELA. See BepiColombo: BepiColombo Laser Altimeter 433 Eros, 195, 196, 339 BepiColombo Laser Altimeter, 554, 557, 558 gravity assists, 555 activation energy, 409, 412 gyroscope, 556 adiabat, 38 HGA. See BepiColombo: high-gain antenna adiabatic decompression melting, 38, 60, 168, 186 high-gain antenna, 556, 560 adiabatic gradient, 96 ISA. See BepiColombo: Italian Spring Accelerometer admittance, 64, 65, 74, 271 Italian Spring Accelerometer, 549, 554, 557, 558 aerodynamic fractionation, 507, 509 Magnetospheric Orbiter Sunshield and Interface, 552, 553, 555, 560 Airy isostasy, 64 MDM. See BepiColombo: Mercury Dust Monitor Al. See aluminum Mercury Dust Monitor, 554, 560–561 Al exosphere. See aluminum exosphere Mercury flybys, 555 albedo, 192, 198 Mercury Gamma-ray and Neutron Spectrometer, 554, 558 compared with other bodies, 196 Mercury Imaging X-ray Spectrometer, 558 Alfvén Mach number, 430, 433, 442, 463 Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter, 552, 553, 554, 555, 556, 557, aluminum, 36, 38, 147, 177, 178–184, 185, 186, 209, 559–561 210 Mercury Orbiter Radio Science Experiment, 554, 556–558 aluminum exosphere, 371, 399–400, 403, 423–424 Mercury Planetary Orbiter, 366, 549, 550, 551, 552, 553, 554, 555, ground-based observations, 423 556–559, 560, 562 andesite, 179, 182, 183 Mercury Plasma Particle Experiment, 554, 561 Andrade creep function, 100 Mercury Sodium Atmospheric Spectral Imager, 554, 561 Andrade rheological model, 100 Mercury Thermal Infrared Spectrometer, 366, 554, 557–558 anorthosite, 30, 210 Mercury Transfer Module, 552, 553, 555, 561–562 anticline, 70, 251 MERTIS. -

Meteorite Impacts, Earth, and the Solar System

Traces of Catastrophe A Handbook of Shock-Metamorphic Effects in Terrestrial Meteorite Impact Structures Bevan M. French Research Collaborator Department of Mineral Sciences, MRC-119 Smithsonian Institution Washington DC 20560 LPI Contribution No. 954 i Copyright © 1998 by LUNAR AND PLANETARY INSTITUTE The Institute is operated by the Universities Space Research Association under Contract No. NASW-4574 with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Material in this volume may be copied without restraint for library, abstract service, education, or personal research purposes; however, republication of any portion thereof requires the written permission of the Insti- tute as well as the appropriate acknowledgment of this publication. Figures 3.1, 3.2, and 3.5 used by permission of the publisher, Oxford University Press, Inc. Figures 3.13, 4.16, 4.28, 4.32, and 4.33 used by permission of the publisher, Springer-Verlag. Figure 4.25 used by permission of the publisher, Yale University. Figure 5.1 used by permission of the publisher, Geological Society of America. See individual captions for reference citations. This volume may be cited as French B. M. (1998) Traces of Catastrophe:A Handbook of Shock-Metamorphic Effects in Terrestrial Meteorite Impact Structures. LPI Contribution No. 954, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. 120 pp. This volume is distributed by ORDER DEPARTMENT Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113, USA Phone:281-486-2172 Fax:281-486-2186 E-mail:[email protected] Mail order requestors will be invoiced for the cost of shipping and handling. Cover Art.“One Minute After the End of the Cretaceous.” This artist’s view shows the ancestral Gulf of Mexico near the present Yucatán peninsula as it was 65 m.y.