Integrating Economic and Sociological Approaches to International Relations?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Me, Myself & Mine: the Scope of Ownership

ME, MYSELF & MINE The Scope of Ownership _________________________________ PETER MARTIN JAWORSKI _________________________________ May, 2012 Committee: Fred Miller (Chair) David Shoemaker, Steven Wall, Daniel Jacobson, Neil Englehart ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is an attempt to defend the following thesis: The scope of legitimate ownership claims is much more narrow than what Lockean liberals have traditionally thought. Firstly, it is more narrow with respect to the particular claims that are justified by Locke’s labour- mixing argument. It is more difficult to come to own things in the first place. Secondly, it is more narrow with respect to the kinds of things that are open to the ownership relation. Some things, like persons and, maybe, cultural artifacts, are not open to the ownership relation but are, rather, fit objects for the guardianship, in the case of the former, and stewardship, in the case of the latter, relationship. To own, rather than merely have a property in, some object requires the liberty to smash, sell, or let spoil the object owned. Finally, the scope of ownership claims appear to be restricted over time. We can lose our claims in virtue of a change in us, a change that makes it the case that we are no longer responsible for some past action, like the morally interesting action required for justifying ownership claims. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Much of this work has benefited from too many people to list. However, a few warrant special mention. My committee, of course, deserves recognition. I’m grateful to Fred Miller for his many, many hours of pouring over my various manuscripts and rough drafts. -

Political Science 270 Mechanisms of International Relations

Political Science 270 Mechanisms of International Relations Hein Goemans Course Information: Harkness 337 Spring 2016 Office Hours: Wed. 2 { 3 PM 16:50{19:30 Wednesday [email protected] Meliora 203 The last fifteen years or so saw a major revolution in the social sciences. Instead of trying to discover and test grand \covering laws" that have universal validity and tremendous scope| think Newton's gravity or Einstein's relativity|the social sciences are in the process of switch- ing to more narrow and middle-range theories and explanations, often referred to as causal mechanisms. Recently, however, a new so-called \behavioral" approach { often but not always complementary { is currently sweeping the field. Since mechanisms remain the core theoretical building blocks in our field, we will continue to focus on them. In the bulk of this course students will be introduced to a range of such causal mechanisms with applications in international relations. Although these causal mechanisms can loosely be described in prose, explicit formalization { e.g., math { allows for a much deeper and richer understanding of the phenomena of study. In other words, formalization enables simplification and thus a better understanding of what is \really" going on. To set us on that path, we begin with some very basic rational choice fundamentals to introduce you to formal models in a rigorous way to show the power and potential of this approach. In other words, there will be some *gasp* Algebra. For much of the very brief but essential introduction to game theory we will use William Spaniel's Channel (http://gametheory101.com/courses/game-theory-101/, also on YouTube), as well as his cheap but very highly rated introductory book Game Theory 101: The Complete Textbook available at Amazon (http://www.amazon.com). -

Making Sense of State Socialization

Review of International Studies (2001), 27, 415–433 Copyright © British International Studies Association Making sense of state socialization KAI ALDERSON Abstract. At present, International Relations scholars use the metaphor of ‘state socializ- ation’ in mutually incompatible ways, embarking from very different starting points and arriving at a bewildering variety of destinations. There is no consensus on what state socializ- ation is, who it affects, or how it operates. This article seeks to chart this relatively unmapped concept by defining state socialization, differentiating it from similar concepts, and exploring what the study of state socialization can contribute to important and longstanding theoretical debates in the field of international relations. Introduction Norms are gaining ground in the study of International Relations.1 Not only are they the focus of extensive conceptual and theoretical work, but international norms are increasingly seen as weight-bearing elements of explanatory theories in issue- areas ranging from national security to the study of international organization.2 Regime theory continues to generate an extraordinarily fecund research pro- gramme,3 and its central insight—that relations among competitive sovereign states are shot through with norms of cooperation—links contemporary scholarship to long-standing reflections on the nature of the international.4 Constructivist scholars, for their part, argue that social norms offer a radical alternative to interest- and power-based accounts of international politics.5 1 As readily attested by the contributions to the recent fiftieth anniversary edition of International Organization, 52: 4 (1998). See, in particular, contributions by Peter J. Katzenstein, Robert O. Keohane and Stephen D. Krasner (esp. -

Adam Przeworski: Capitalism, Democracy and Science

ADAM PRZEWORSKI: CAPITALISM, DEMOCRACY AND SCIENCE Interview with Adam Przeworski conducted and edited by Gerardo L. Munck February 24, 2003, New York, New York Prepared for inclusion in Gerardo L. Munck and Richard Snyder, Passion, Craft, and Method in Comparative Politics. Training and Intellectual Formation: From Poland to the United States Q: How did you first get interested in studying politics? What impact did growing up in Poland have on your view of politics? A: Given that I was born in May of 1940, nine months after the Germans had invaded and occupied Poland, any political event, even a minor one, was immediately interpreted in terms of its consequences for one’s private life. All the news was about the war. I remember my family listening to clandestine radio broadcasts from the BBC when I was three or four years old. After the war, there was a period of uncertainty, and then the Soviet Union basically took over. Again, any rumbling in the Soviet Union, any conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States, was immediately seen in terms of its consequences for our life. It was like this for me until I first left for the US in 1961, right after the Berlin Wall went up. One’s everyday life was permeated with international, macro-political events. Everything was political. But I never thought of studying politics. For one thing, in Europe at that time there really was no political science. What we had was a German and Central European tradition that was called, translating from German, “theory of the state and law.” This included Carl Schmitt and Hans Kelsen, the kind of stuff that was taught normally at law schools. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. A LeftLeft----LibertarianLibertarian Theory of Rights Arabella Millett Fisher PhD University of Edinburgh 2011 Contents Abstract....................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................v Declaration.................................................................................................................. vi Introduction..................................................................................................................1 Part I: A Libertarian Theory of Justice...................................................................11 -

The Culture of National Security the Culture of National Security: Norms and Identity in World Politics Peter J

The Culture of National Security The Culture of National Security: Norms and Identity in World Politics Peter J. Katzenstein New York COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS 1996 Bibliographic Data Preface Contributors 1.Introduction: Alternative Perspectives on National Security Peter J. Katzenstein 2.Norms, Identity, and Culture in National Security Ronald L. Jepperson, Alexander Wendt, and Peter J. Katzenstein Part I. Norms and National Security 3.Status, Norms, and the Proliferation of Conventional Weapons: An Institutional Theory Approach Dana P. Eyre and Mark C. Suchman 4.Norms and Deterrence: The Nuclear and Chemical Weapons Taboos Richard Price and Nina Tannenwald http://www.ciaonet.org/book/katzenstein/index.html (1 of 2) [8/9/2002 1:46:59 PM] The Culture of National Security 5.Constructing Norms of Humanitarian Intervention Martha Finnemore 6.Culture and French Military Doctrine Before World War II Elizabeth Kier 7.Cultural Realism and Strategy in Maoist China Alastair Iain Johnston Part II. Identity and National Security 8. Identity, Norms, and National Security: The Soviet Foreign Policy Revolution and the End of the Cold War Robert G. Herman 9. Norms, Identity, and National Security in Germany and Japan Thomas U. Berger 10.Collective Identity in a Democratic Community: The Case of NATO Thomas Risse-Kappen 11.Identity and Alliances in the Middle East Michael N. Barnett Part III. Implications and Conclusions 12.Norms, Identity, and Their Limits: A Theoretical Reprise Paul Kowert and Jeffrey Legro 13.Conclusion: National Security in a Changing World Peter J. Katzenstein Pagination [an error occurred while processing this directive] http://www.ciaonet.org/book/katzenstein/index.html (2 of 2) [8/9/2002 1:46:59 PM] The Culture of National Security The Culture of National Security: Norms and Identity in World Politics, by Peter J. -

What Egalitarianism Requires: an Interview with John E. Roemer

Erasmus Journal for Philosophy and Economics, Volume 13, Issue 2, Winter 2020, pp. 127–176. https://doi.org/10.23941/ejpe.v13i2.530 What Egalitarianism Requires: An Interview with John E. Roemer JOHN E. ROEMER (Washington, 1945) is the Elizabeth S. and A. Varick Stout Professor of Political Science and Economics at Yale University, where he has taught since 2000. Before joining Yale, he had taught at the University of California, Davis, since 1974. He is also a Fellow of the Econ- ometric Society, and has been a Fellow of the Guggenheim Foundation, and the Russell Sage Foundation. Roemer completed his undergraduate studies in mathematics at Harvard in 1966, and his graduate studies in economics at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1974. Roemer’s work spans the domains of economics, philosophy, and po- litical science, and, most often, applies the tools of general equilibrium and game theory to problems of political economy and distributive jus- tice—problems often stemming from the discussions among political phi- losophers in the second half of the twentieth century. Roemer is one of the founders of the Anglo-Saxon tradition of analytical Marxism, particu- larly in economics, and a member of the September Group—together with Gerald A. Cohen and Jon Elster, among others—since its beginnings in the early 1980s. Roemer is most known for his pioneering work on various types of exploitation, including capitalist and Marxian exploitation (for example, A General Theory of Exploitation and Class, 1982a), for his ex- tensive writings on Marxian economics and philosophy (for example, An- alytical Foundations of Marxian Economic Theory, 1981, and Free to Lose: An Introduction to Marxist Economic Philosophy, 1988a), for his numerous writings on socialism (for example, A Future for Socialism, 1994b), and for his work on the concept and measurement of equality of opportunity (for example, Equality of Opportunity, 1998a). -

Marxism and the Continuing Irrelevance of Normative Theory (Reviewing G

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2002 Marxism and the Continuing Irrelevance of Normative Theory (reviewing G. A. Cohen, If You're an Egalitarian, How Come You're So Rich? (2000)) Brian Leiter Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Brian Leiter, "Marxism and the Continuing Irrelevance of Normative Theory (reviewing G. A. Cohen, If You're an Egalitarian, How Come You're So Rich? (2000))," 54 Stanford Law Review 1129 (2002). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEW Marxism and the Continuing Irrelevance of Normative Theory Brian Leiter* IF YOU'RE AN EGALITARIAN, How COME YOU'RE SO RICH? By G. A. Cohen. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000. 237 pp. $18.00. I. INTRODUCTION G. A. Cohen, the Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory at Oxford, first came to international prominence with his impressive 1978 book on Marx's historical materialism,1 a volume which gave birth to "analytical Marxism."'2 Analytical Marxists reformulated, criticized, and tried to salvage central features of Marx's theories of history, ideology, politics, and economics. They did so not only by bringing a welcome argumentative rigor and clarity to the exposition of Marx's ideas, but also by purging Marxist thinking of what we may call its "Hegelian hangover," that is, its (sometimes tacit) commitment to Hegelian assumptions about matters of both philosophical substance and method. -

Constitutionalism in Eastern Europe: an Introduction Author(S): Jon Elster Source: the University of Chicago Law Review, Vol

Constitutionalism in Eastern Europe: An Introduction Author(s): Jon Elster Source: The University of Chicago Law Review, Vol. 58, No. 2, Approaching Democracy: A New Legal Order for Eastern Europe, (Spring, 1991), pp. 447-482 Published by: The University of Chicago Law Review Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1599963 Accessed: 10/06/2008 15:42 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=uclr. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org ARTICLES Constitutionalism in Eastern Europe: An Introduction Jon Elstert Since 1989, seven countries in Eastern Europe have under- taken the transition from one-party rule to constitutional democ- racy: Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Yugoslavia. -

The Lawyer's Role(S) in Deliberative Democracy*

THE LAWYER'S ROLE(S) IN DELIBERATIVE DEMOCRACY* Carrie Menkel-Meadow** "[Lawyers] serve as arbiters between the citizens."1 I. INTRODUCTION: DEMOCRATIC THEORY, PRACTICE AND LAWYERS As legal theorists and academics we are drawn to grand meta-narratives about governing institutions, democracies, political theories and the role of law, citizens and elites in helping us to understand what are the best normative sys- tems for us to use in governing ourselves. As a legal pragmatist and sometimes legal clinician and practitioner, I have long been concerned with how our grand theories operate in the empirical world. Can we make democratic theories really work? What are the conditions that foster democratic participation or good "democratic discourse" as current political theory describes it? What might be the role of the lawyer in constructing and facilitating "optimal" or "productive" democratic discourse? Are current institutions and current role enactments up to the task of fostering democracy or should we consider new forms of institutions and new legal and political roles? What challenges do new institutions and new roles present to our older, deeply structured institutions and roles - such as the Constitution, the political party system, the separation of powers, federalism and the adversary system? As a conflict resolution theorist and practitioner, I have noted that the empirical world has changed greatly from the times in which most of our legal and political institutions were conceptualized and created. Political and legal issues are now often multi-partied and multi-issued,2 suggesting that older con- * © 2005 Carrie Menkel-Meadow ** Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center; Director, Georgetown-Hewlett Program in Conflict Resolution and Legal Problem Solving; Chair, CPR-Georgetown Commission on Ethics and Standards in ADR. -

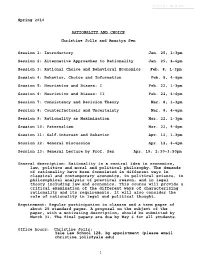

Rationality and Choice

Spring 2010 RATIONALITY AND CHOICE Christine Jolls and Amartya Sen Session 1: Introductory Jan. 25, 1-3pm Session 2: Alternative Approaches to Rationality Jan. 25, 4-6pm Session 3: Rational Choice and Behavioral Economics Feb. 8, 1-3pm Session 4: Behavior, Choice and Information Feb. 8, 4-6pm Session 5: Heuristics and Biases: I Feb. 22, 1-3pm Session 6: Heuristics and Biases: II Feb. 22, 4-6pm Session 7: Consistency and Decision Theory Mar. 8, 1-3pm Session 8: Counterfactuals and Uncertainty Mar. 8, 4-6pm Session 9: Rationality as Maximization Mar. 22, 1-3pm Session 10: Paternalism Mar. 22, 4-6pm Session 11: Self-interest and Behavior Apr. 12, 1-3pm Session 12: General Discussion Apr. 12, 4-6pm Session 13: General Lecture by Prof. Sen Apr. 19, 2:30-3:50pm General description: Rationality is a central idea in economics, law, politics and moral and political philosophy. The demands of rationality have been formulated in different ways in classical and contemporary economics, in political science, in philosophical analysis of practical reason, and in legal theory including law and economics. This course will provide a critical examination of the different ways of characterizing rationality and its requirements. It will also consider the role of rationality in legal and political thought. Requirement: Regular participation in classes and a term paper of about 25 standard pages. A proposal on the subject of the paper, with a motivating description, should be submitted by March 31. The final papers are due by May 6 for all students. Office hours: Christine Jolls: Yale Law School 128, by appointment (please email [email protected]) 1 Amartya Sen: Mondays 11-12, Littauer Center 205, no appointment needed Tuesdays 11-12, Littauer Center 205, by appointment (please call 5-1871) General readings: The following books may be used as general reference: Richard Thaler, Quasi Rational Economics. -

Sociological Theory 2020

UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD Department of Sociology Sociological Theory Honour School of Philosophy, Politics, and Economics (218) Honour School of History and Politics (218) Honour School of Human Sciences (5b) Academic Year 2021/22 In this paper you will investigate a variety of theoretical perspectives on social life. Some perspectives examine how social structures are built up from individual action, whether driven by evolutionary psychology, decided by rational choice, or motivated by meaningful values. Others identify the emergent properties of social life, ranging from face-to-face interaction to social networks to systems of oppression. You will use these perspectives to investigate substantive problems. Why do social norms change? How do some groups manage to solve problems of collective action? What similarities exist between states and mafias? Throughout, you will learn how the insights of classical sociologists are being advanced in contemporary research. Convenor Dr Michael Biggs ([email protected]) Tutors Mr Kasimir Dederichs, Nuffield Mr Mathis Ebbinghaus, Nuffield Mr Clemens Jarnach, Green Templeton Ms Brittany Klug, Wolfson Dr Jonathan Lusthaus, Nuffield Prof Lois McNay, Somerville Ms Scarlett Ng, St Antony’s Dr André Nilsen, Hertford Dr Amanda Palmer, Harris Manchester Mr Ran Ren, St Anne’s Mr Yoav Roll, Nuffield Syllabus Theoretical perspectives which may include rational choice; evolutionary psychology; interpersonal interaction; social integration and networks; functionalism. Substantive problems which may include stratification; gender; nationalism, race and ethnicity; collective action; norms; ideology; economic development; gangs and organized crime. Candidates will be expected to use theories to explain substantive problems. Teaching Dr Michael Biggs gives 8 lectures on Theoretical Perspectives in Michaelmas Term.