E-Print © BERG PUBLISHERS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2010

International I F L A Preservation PP AA CC o A Newsletter of the IFLA Core Activity N . 52 News on Preservation and Conservation December 2010 Tourism and Preservation: Some Challenges INTERNATIONAL PRESERVATION Tourism and Preservation: No 52 NEWS December 2010 Some Challenges ISSN 0890 - 4960 International Preservation News is a publication of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) Core 6 Activity on Preservation and Conservation (PAC) The Economy of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Conservation that reports on the preservation Valéry Patin activities and events that support efforts to preserve materials in the world’s libraries and archives. 12 IFLA-PAC Bibliothèque nationale de France Risks Generated by Tourism in an Environment Quai François-Mauriac with Cultural Heritage Assets 75706 Paris cedex 13 France Miloš Drdácký and Tomáš Drdácký Director: Christiane Baryla 18 Tel: ++ 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 70 Fax: ++ 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 80 Cultural Heritage and Tourism: E-mail: [email protected] A Complex Management Combination Editor / Translator Flore Izart The Example of Mauritania Tel: ++ 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 71 Jean-Marie Arnoult E-mail: fl [email protected] Spanish Translator: Solange Hernandez Layout and printing: STIPA, Montreuil 24 PAC Newsletter is published free of charge three times a year. Orders, address changes and all The Challenge of Exhibiting Dead Sea Scrolls: other inquiries should be sent to the Regional Story of the BnF Exhibition on Qumrân Manuscripts Centre that covers your area. 3 See -

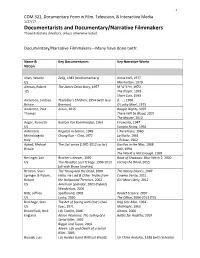

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

Ecopsychology

E u r o p e a n J o u r n a l o f Ecopsychology Special Issue: Ecopsychology and the psychedelic experience Edited by: David Luke Volume 4 2013 European Journal of Ecopsychology EDITOR Paul Stevens, The Open University, UK ASSOCIATE EDITORS Martin Jordan, University of Brighton, UK Martin Milton, University of Surrey, UK Designed and formatted using open source software. EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Matthew Adams, University of Brighton, UK Meg Barker, The Open University, UK Jonathan Coope, De Montfort University, UK Lorraine Fish, UK Jamie Heckert, Anarchist Studies Network John Hegarty, Keele University, UK Alex Hopkinson, Climate East Midlands, UK David Key, Footprint Consulting, UK Alex Lockwood, University of Sunderland, UK David Luke, University of Greenwich, UK Jeff Shantz, Kwantlen Polytechnic University, Canada FOCUS & SCOPE The EJE aims to promote discussion about the synthesis of psychological and ecological ideas. We will consider theoretical papers, empirical reports, accounts of therapeutic practice, and more personal reflections which offer the reader insight into new and original aspects of the interrelationship between humanity and the rest of the natural world. Topics of interest include: • Effects of the natural environment on our emotions and wellbeing • How psychological disconnection relates to the current ecological crisis • Furthering our understanding of psychological, emotional and spiritual relationships with nature For more information, please see our website at http://ecopsychology-journal.eu/ or contact us via email: -

6X9 End of World Msalphabetical

THE END OF THE WORLD PROJECT Edited By RICHARD LOPEZ, JOHN BLOOMBERG-RISSMAN AND T.C. MARSHALL “Good friends we have had, oh good friends we’ve lost, along the way.” For Dale Pendell, Marthe Reed, and Sudan the white rhino TABLE OF CONTENTS Editors’ Trialogue xiii Overture: Anselm Hollo 25 Etel Adnan 27 Charles Alexander 29 Will Alexander 42 Will Alexander and Byron Baker 65 Rae Armantrout 73 John Armstrong 78 DJ Kirsten Angel Dust 82 Runa Bandyopadhyay 86 Alan Baker 94 Carlyle Baker 100 Nora Bateson 106 Tom Beckett 107 Melissa Benham 109 Steve Benson 115 Charles Bernstein 117 Anselm Berrigan 118 John Bloomberg-Rissman 119 Daniel Borzutzky 128 Daniel f Bradley 142 Helen Bridwell 151 Brandon Brown 157 David Buuck 161 Wendy Burk 180 Olivier Cadiot 198 Julie Carr / Lisa Olstein 201 Aileen Cassinetto and C. Sophia Ibardaloza 210 Tom Cohen 214 Claire Colebrook 236 Allison Cobb 248 Jon Cone 258 CA Conrad 264 Stephen Cope 267 Eduardo M. Corvera II (E.M.C. II) 269 Brenda Coultas 270 Anne Laure Coxam 271 Michael Cross 276 Thomas Rain Crowe 286 Brent Cunningham 297 Jane Dalrymple-Hollo 300 Philip Davenport 304 Michelle Detorie 312 John DeWitt 322 Diane Di Prima 326 Suzanne Doppelt 334 Paul Dresman 336 Aja Couchois Duncan 346 Camille Dungy 355 Marcella Durand 359 Martin Edmond 370 Sarah Tuss Efrik and Johannes Göransson 379 Tongo Eisen-Martin 397 Clayton Eshleman 404 Carrie Etter 407 Steven Farmer 409 Alec Finlay 421 Donna Fleischer 429 Evelyn Flores 432 Diane Gage 438 Jeannine Hall Gailey 442 Forrest Gander 448 Renée Gauthier 453 Crane Giamo 454 Giant Ibis 459 Alex Gildzen 460 Samantha Giles 461 C. -

Chauvet Cave: Man's First Masterpiece

ARDÈCHE CAVES few kilometres from the village of Vallon-Pont- So here I am, the last journalist to be allowed in before the d’Arc, the hub of the Gorges de l’Ardèche, lies gala opening in April. My minder is Élisabeth Cayrel, who put France’s most ambitious tourist project for decades together the proposal to have the Chauvet cave declared A– a €55 million replica of a prehistoric cave, a Unesco World Heritage site, a feat achieved in June 2014. painstakingly re-creating one of the most extraordinary finds of She has already given me the facts, the numbers and the gossip: our times. The architects Fabre-Speller wanted the building to how the name Caverne du Pont-d’Arc was chosen to distinguish be subsumed in the environment, which explains why, to reach the replica from the Grotte Chauvet after negotiations with it from the car park, I must stroll under the shade of green oaks Jean-Marie Chauvet to license his name broke down; how and saunter through wild boxwood bushes and juniper shrubs. a troop of chemists is re-creating the humidity and musty smell Like many great discoveries, chance played a big role. of the ancient sealed cave; or how a 3D scan has ensured that On 18 December, 1994, three cavers – Jean-Marie Chauvet, the geomorphology of the original has been fully reproduced. Éliette Brunel and Christian Hillaire – noticed a small cavity With a surface area of 3,500 square metres – around one-third 80 centimetres by 30 centimetres in the cliffs of the Cirque that of the real cave – and 439 reproductions out of the 450 d’Estre in the Ardèche département. -

Journal of Arts & Humanities

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 08, Issue 12, 2019: 01-10 Article Received: 31-10-2019 Accepted: 25-11-2019 Available Online: 14-12-2019 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v8i12.1780 From Cave to Screen: A Study of the Shamanic Origins of Filmmaking Lila Moore1 ABSTRACT This article is a study of the shamanic origins of cinema and the processes and elements involved in filmmaking and film viewing that recall shamanic and ritualistic practices. It interweaves several studies alongside theoretical and creative concepts concerning the shamanic origins of art and film, starting with Werner Herzog’s statement from his film Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010) that the Chauvet Cave art constitutes a proto-cinema. In this study, a comparative analysis of the archetypal structure of the cave’s proto-cinema and the basic structure of Australian Aboriginal rituals demonstrates that they share common characteristics. These characteristics are associated with the contemporary cinematic apparatus. Moreover, Herzog’s approach to the cave art as a cinematic shaman initiating the film’s viewers is detailed in order to demonstrate the parallels between the shamanic and ritualistic technology and features of the cave art and the modern technology and awareness involved in moving images, filmmaking and film viewing. David Lewis-Williams’ neuropsychological model of altered states of consciousness as a basis for our understanding of Upper Paleolithic cave art allows further articulations of the characteristics of the shamanic experience as generated by the aesthetics of the cinematic medium. In addition, the article implies that exploration of the interrelations of contemporary cinematic aesthetics and ancient shamanic depictions may trigger further insights on the evolution of human creativity and aesthetic forms through the integration of technological and spiritual means and expressions. -

Cave of Forgotten Dreams

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 15 Issue 1 April 2011 Article 2 April 2011 Cave of Forgotten Dreams Jeremy Biles The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Biles, Jeremy (2011) "Cave of Forgotten Dreams," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 15 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol15/iss1/2 This Film Review is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cave of Forgotten Dreams Abstract This is a film review of Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010). This film er view is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol15/iss1/2 Biles: Cave of Forgotten Dreams “All caves are sacred,” historian of religions Doris Heyden has written. Uncanny in their mingling of fascination and fear, caves exemplify the mysterium tremendum et fascinans that Rudolf Otto famously identified as the experience of the sacred. And caves are symbols of birth and death, passages between worlds— at once wombs and tombs. Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams, filmed magnificently in 3D, explores and evokes the sacred dimensions of the Cave of Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc, located along the Ardèche River in southern France. Discovered in 1994 by a trio of speleologists headed by Jean-Marie Chauvet, this winding subterranean labyrinth spans the space of a football field. -

Still Einstellung: Stillmoving Imagenesis Jon Inge Faldalen

Still Einstellung: Stillmoving Imagenesis Jon Inge Faldalen Discourse, Volume 35, Number 2, Spring 2013, pp. 228-247 (Article) Published by Wayne State University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/546677 Access provided by UNIVERSITY OF THE ARTS, LONDON (18 Apr 2017 14:52 GMT) Still Einstellung: Stillmoving Imagenesis Jon Inge Faldalen Persons do not mirror themselves in run- ning water—they mirror themselves in still water. Only what is still can still the stillness of other things. —Confucius [T]he artist was so overwhelmed by the splendor of the Buddha that he could not draw when looking at him directly. When the situation was presented to the Bud- dha, he said, “Let us go together to the bank of a clear and limpid pool”; where- upon the Buddha sat himself by the bank of the pool, while the artist sketched his drawing based upon the reflection on the water’s surface. This particular style became known as “the image of the Sage taken from (a reflection in) water.” —Lama Gega O Thou who changest not, abide with me. —Henry Francis Lyte, “Abide with Me,” 1847 Discourse, 35.2, Spring 2013, pp. 228–247. Copyright © 2014 Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201-1309. ISSN 1522-5321. Still Einstellung 229 Reflections and shadows—drawn lightly on the fluid or fixed sur- faces of water and rock—dissolve the dichotomy of still versus mov- ing images, provoking a third concept: stillmoving imagenesis, or a simultaneous becoming of still and moving images. From Narcis- sus to Nosferatu, reflections and shadows have been discussed as significant others of things in myth, religion, philosophy, art, sci- ence, and popular culture. -

Drawings of Representational Images by Upper

Drawings of Representational Images by Upper Paleolithic Humans and their Absence in Neanderthals Reflect Historical Differences in Hunting Wary Game Author(s): Richard G. Coss Source: Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture, Vol. 1, No. 2 (Fall 2017), pp. 15-38 Published by: Academic Studies Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.26613/esic.1.2.46 Accessed: 13-07-2018 21:34 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.26613/esic.1.2.46?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Academic Studies Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture This content downloaded from 99.113.71.51 on Fri, 13 Jul 2018 21:34:54 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms ESIC 2017 DOI: 10.26613/esic/1.2.46 Drawings of Representational Images by Upper Paleolithic Humans and their Absence in Neanderthals Reflect Historical Differences in Hunting Wary Game Richard G. Coss Abstract One characteristic of the transition from the Middle Paleolithic to the Upper Paleolithic in Europe was the emergence of representational charcoal drawings and engravings by Aurignacian and Gravettian artists. -

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Drawings of representational images by upper paleolithic humans and their absence in neanderthals reflect historical differences in hunting wary game Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0042x9vr Journal Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture, 1(2) ISSN 2472-9884 Author Coss, RG Publication Date 2017-09-01 DOI 10.26613/esic.1.2.46 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Drawings of Representational Images by Upper Paleolithic Humans and their Absence in Neanderthals Reflect Historical Differences in Hunting Wary Game Author(s): Richard G. Coss Source: Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture, Vol. 1, No. 2 (Fall 2017), pp. 15-38 Published by: Academic Studies Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.26613/esic.1.2.46 Accessed: 13-07-2018 21:34 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.26613/esic.1.2.46?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Academic Studies Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture This content downloaded from 99.113.71.51 on Fri, 13 Jul 2018 21:34:54 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms ESIC 2017 DOI: 10.26613/esic/1.2.46 Drawings of Representational Images by Upper Paleolithic Humans and their Absence in Neanderthals Reflect Historical Differences in Hunting Wary Game Richard G. -

3D Moving Images As Cartographies of Time

7. Surface Explorations: 3D Moving Images as Cartographies of Time Nanna Verhoeff Abstract In this essay, I examine how the trope of navigation in 3D moving images can work towards an intimate and haptic encounter with other times and other places. The particular navigational construction of space in time in 3D moving images can be considered a cartography of time. This is a haptic cartography of exploration of the surfaces on which this encounter takes place. Taking Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010) as a theoretical object, the main question addressed is how the creative exploration of new visualization technologies—from rock painting and principles of animation to 3D moving images—entails an epistemological inquiry into, and statements about, the power of images, technologies of vision, and the media cartographies they make. Keywords: Surface, cartography; navigation; 3D, animation; haptic visuality Explorations Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), a 3D documentary about the prehistoric cave paintings in Chauvet in the south of France, raises questions about the relationship between image, technology, and epistemol- ogy. The film shows striking and vibrant Paleolithic drawings, mostly of animals, from more than 30,000 years ago. The depiction of galloping herds of animals is characterized by a high sense of motion, and the bulges and contours of the rocky surface create a striking effect of three-dimensionality to the images. By navigating through the space, the film camera charts the spatial structure of the cave with its labyrinth of corridors, walls, niches, Sæther, S.Ø. and S.T. Bull (eds.), Screen Space Reconfigured. -

The Documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams: Activities in Teacher Training in Physics

The Documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams: Activities in Teacher Training in Physics Aldo Aoyagui Gomes Pereira Professor at the Federal Institute of Education, Science, and Technology of Sao Paulo – Piracicaba campus E-mail: [email protected] Maria José Pereira Monteiro de Almeida Professor of the Graduate Program in Education and Science and Mathematics Teaching at the University of Campinas E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: In this study, we engaged four Resumo: Neste trabalho desenvolvemos undergraduate students of a physics course um conjunto de atividades com quatro in a set of activities using the documentary licenciandos de um curso de física uti- Cave of forgotten dreams, produced and lizando o documentário A caverna dos directed in 2010 by Werner Herzog. In these sonhos esquecidos, do diretor alemão activities, we discussed how the carbon-14 Werner Herzog, produzido em 2010. Nes- dating of the cave paintings depicted in sas atividades, discutimos por que o uso the documentary has influenced the field of da datação por carbono 14 nas pinturas archaeology. In addition, we problematized rupestres retratadas no documentário cau- some aspects of the students’ interpreta- sou impacto na área arqueológica. Além tion of the images and narrative of the disso, problematizamos alguns elementos documentary. The information analyzed was da leitura de imagens e a narrativa desse collected through video recordings and the documentário. A coleta de informações written production of the undergraduates. se deu por meio de gravações em vídeo The analysis was based on the concepts and e da produção escrita dos licenciandos. A principles of Discourse Analysis as appear análise foi realizada a partir de princípios in texts of Eni Orlandi published in Brazil.