Ecopsychology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2010

International I F L A Preservation PP AA CC o A Newsletter of the IFLA Core Activity N . 52 News on Preservation and Conservation December 2010 Tourism and Preservation: Some Challenges INTERNATIONAL PRESERVATION Tourism and Preservation: No 52 NEWS December 2010 Some Challenges ISSN 0890 - 4960 International Preservation News is a publication of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) Core 6 Activity on Preservation and Conservation (PAC) The Economy of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Conservation that reports on the preservation Valéry Patin activities and events that support efforts to preserve materials in the world’s libraries and archives. 12 IFLA-PAC Bibliothèque nationale de France Risks Generated by Tourism in an Environment Quai François-Mauriac with Cultural Heritage Assets 75706 Paris cedex 13 France Miloš Drdácký and Tomáš Drdácký Director: Christiane Baryla 18 Tel: ++ 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 70 Fax: ++ 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 80 Cultural Heritage and Tourism: E-mail: [email protected] A Complex Management Combination Editor / Translator Flore Izart The Example of Mauritania Tel: ++ 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 71 Jean-Marie Arnoult E-mail: fl [email protected] Spanish Translator: Solange Hernandez Layout and printing: STIPA, Montreuil 24 PAC Newsletter is published free of charge three times a year. Orders, address changes and all The Challenge of Exhibiting Dead Sea Scrolls: other inquiries should be sent to the Regional Story of the BnF Exhibition on Qumrân Manuscripts Centre that covers your area. 3 See -

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

Evolution and Executive Functions: Why Our Toolboxes Are Empty

Revista Española de Neuropsicología 4, 4:351-377 (2002) Copyright© 2002 de REN ISSN: 1139-9872 Evolution and executive functions: Why our toolboxes are empty Roy Sugarman PhD Royal Adelaide Hospital: Glenside Campus Dept of Psychiatry, Adelaide University Abstract: Despite the recent findings with regard to our origins as human primates, we still struggle to find tools that evaluate executive functioning adequately and reliably. Despite some evidence of ecological validity, our toolboxes remain largely empty. With regard to how we produce common behaviours by using individually distinct, multiple areas of focus, each brain is individual. In a sense, not many complex, human, behaviours follow a normal distribution. This work traces the probable origins of executive functioning in humans in a social context, defining in passing the nature of human self-regulation. A discussion follows which integrates these ideas within a second order, cybernetic neuroepistemology of human thought and emotion, and questions the logical paradox of assuming that isolated cortical areas such as the frontal lobes generate executive functions in a linear progression. A brief exploration follows with regard to the nature of human consciousness, and the difficulties in measuring such a homeostatic mechanism as executive function. Using alcohol related brain changes, and cross-cultural issues as exemplars, an attempt is made to define a neuroepistemology for understanding the dynamic interplay between executive function and consciousness. Key words: Brain´s Evolution, executive functioning. Evolución y funciones ejecutivas: por qué nuestras cajas de herramientas estan vacías Resumen: A pesar de los recientes hallazgos en relación a nuestros orígenes como humanos primates, aún luchamos para encontrar instrumentos que evalúen el funcionamiento ejecutivo adecuadamente y de manera fiable. -

Proceedings of the Inaugural Meeting Ofais Sigprag Par Agerfalk Uppsala University, [email protected]

Association for Information Systems AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) All Sprouts Content Sprouts 9-1-2010 Proceedings of the Inaugural Meeting ofAIS SIGPrag Par Agerfalk Uppsala University, [email protected] Mark Aakhus Rutgers University, [email protected] Mikael Lind Viktoria Institute, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://aisel.aisnet.org/sprouts_all Recommended Citation Agerfalk, Par; Aakhus, Mark; and Lind, Mikael, " Proceedings of the Inaugural Meeting ofAIS SIGPrag" (2010). All Sprouts Content. 253. http://aisel.aisnet.org/sprouts_all/253 This material is brought to you by the Sprouts at AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). It has been accepted for inclusion in All Sprouts Content by an authorized administrator of AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Working Papers on Information Systems ISSN 1535-6078 Proceedings of the Inaugural Meeting of AIS SIGPrag Pär Ãgerfalk Uppsala University, Sweden Mark Aakhus Rutgers University, USA Mikael Lind Viktoria Institute, Sweden Abstract The Special Interest Group on Pragmatist IS Research (SIGPrag) was approved by the Association for Information Systems (AIS) council at its June 2008 meeting in Gallway. The motivation for this initiative is the growing recognition of the importance of theorizing the IT artifact and its organizational and societal context from a pragmatic and action-oriented perspective. SIGPragâs mission is to provide a much-needed centre of gravity and to facilitate exchange of ideas and further development of this area of IS scholarship. In summary, pragmatist IS research rests on the following set of assumptions: ⢠Human life is a life of activity. -

E-Print © BERG PUBLISHERS

Time and Mind: The Journal of “But the Image Wants Archaeology, Danger”: Georges Consciousness and Culture Bataille, Werner Volume 5—Issue 1 March 2012 Herzog, and Poetical pp. 33–52 Response to Paleoart DOI: 10.2752/175169712X13182754067386 Reprints available directly Barnaby Dicker and Nick Lee from the publishers Photocopying permitted by licence only Barnaby Dicker teaches at UCA Farnham and is Historiographic Officer at the International Project Centre © Berg 2012 for Research into Events and Situations (IPCRES), Swansea Metropolitan University. His research revolves around conceptual and material innovations in and through graphic technologies and arts. [email protected] Nick Lee is studying for a PhD in the Media Arts Department, Royal Holloway, University of London, which examines the epistemological basis for Marcel Duchamp’s abandonment of painting. He also teaches at the department. [email protected] E-PrintAbstract The high-profile theatrical release of Werner Herzog’s feature-lengthPUBLISHERS documentary filmCave of Forgotten Dreams in Spring 2011 invites reflection on the way in which paleoart is and has been engaged with at a cultural level. By Herzog’s own account, the film falls on the side of poetry, rather than science. This article considers what is at stake in a “poetical” engagement with the scientific findings concerning paleoart and argues that such approaches harbor value for humanity’s understanding of its own history. To this end, Herzog’s work is brought into BERGdialogue with Georges Bataille’s writing on paleoart, in particular, Lascaux—a precedent of poetical engagement. Keywords: Georges Bataille, Werner Herzog, Chauvet © cave, Lascaux Cave, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, poetical methodologies, disciplinary limits, lens-based media Time and Mind Volume 5—Issue 1—March 2012, pp. -

Andrew B. Newberg Page 1 Curriculum Vitae

Andrew B. Newberg Page 1 Curriculum Vitae Andrew B. Newberg, M.D. Education: 8/84-5/88 B.A. Haverford College Haverford, PA 19034 8/88-5/93 M.D. University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine Philadelphia, PA 19104 Postgraduate Training and Fellowship Appointments: 6/93-6/94 Internship in Internal Medicine, Graduate Hospital, Philadelphia, PA 19134 7/94-6/96 Residency in Internal Medicine, Graduate Hospital, Philadelphia, PA 19134 7/96-6/97 Chief Resident, in Internal Medicine, Graduate Hospital, Philadelphia, PA 19134 7/97-6/98 Fellow, Division of Nuclear Medicine, Department of Radiology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA 19104 7/97-1/98 Chief Fellow, Division of Nuclear Medicine, Department of Radiology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA 19104 Faculty Appointments: 7/94-6/97 Assistant Instructor, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine 7/98-11/99 Clinical Assistant Professor of Radiology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine 7/97-7/99 Instructor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine 12/99-6/06 Assistant Professor of Radiology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine 6/03-10/10 Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine 10/05-10/10 Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Religious Studies, University of Pennsylvania, School of Arts and Sciences 7/06-10/10 Associate Professor of Radiology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine 10/10-present Professor of Emergency Medicine, Thomas Jefferson University and Hospital 10/10-present Professor of Radiology, Thomas Jefferson University and Hospital 7/15-present Adjunct Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania, School of Arts and Sciences Hospital and Administrative Appointments: Andrew B. -

Religion in an Age of Science by Ian Barbour

Religion in an Age of Science return to religion-online 47 Religion in an Age of Science by Ian Barbour Ian G. Barbour is Professor of Science, Technology, and Society at Carleton College, Northefiled, Minnesota. He is the author of Myths, Models and Paradigms (a National Book Award), Issues in Science and Religion, and Science and Secularity, all published by HarperSanFrancisco. Published by Harper San Francisco, 1990. This material was prepared for Religion Online by Ted and Winnie Brock. (ENTIRE BOOK) An excellent and readable summary of the role of religion in an age of science. Barbour's Gifford Lectures -- the expression of a lifetime of scholarship and deep personal conviction and insight -- including a clear and helpful analysis of process theology. Preface What is the place of religion in an age of science? How can one believe in God today? What view of God is consistent with the scientific understanding of the world? My goals are to explore the place of religion in an age of science and to present an interpretation of Christianity that is responsive to both the historical tradition and contemporary science. Part 1: Religion and the Methods of Science Chapter 1: Ways of Relating Science and Religion A broad description of contemporary views of the relationship between the methods of science and those of religion: Conflict, Independence, Dialogue, and Integration. Chapter 2: Models and Paradigms This chapter examines some parallels between the methods of science and those of religion: the interaction of data and theory (or experience and interpretation); the historical character of the interpretive community; the use of models; and the influence of paradigms or programs. -

The Neuroscientific Study of Religious and Spiritual Phenomena: Or Why God Doesn’T Use Biostatistics

THE NEUROSCIENTIFIC STUDY OF RELIGIOUS AND SPIRITUAL PHENOMENA: OR WHY GOD DOESN’T USE BIOSTATISTICS by Andrew B. Newberg and Bruce Y. Lee Abstract. With the rapidly expanding field of neuroscience re- search exploring religious and spiritual phenomena, there have been many perspectives as to the validity, importance, relevance, and need for such research. In this essay we review the studies that have con- tributed to our current understanding of the neuropsychology of re- ligious phenomena. We focus on methodological issues to determine which areas have been weaknesses and strengths in the current stud- ies. This area of research also poses important theological and episte- mological questions that require careful consideration if both the religious and scientific elements are to be appropriately respected. The best way to evaluate this field is to determine the methodologi- cal issues that currently affect the field and explore how best to ad- dress such issues so that future investigations can be as robust as possible and can become more mainstream in both the religious and the scientific arenas. Keywords: health; methodology; religion; spirituality. With the rapidly expanding field of research exploring religious and spiri- tual phenomena, there have been many perspectives as to the validity, im- portance, relevance, and need for such research. There is also the ultimate issue of how such research should be interpreted with regard to epistemo- logical questions. The best way to evaluate this field is to determine the methodological issues that currently affect the field and explore how best Andrew B. Newberg, M.D., is assistant professor of radiology and psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania Health System, 110 Donner Building, H.U.P., 3400 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail [email protected]. -

Comments on Donald T. Campbell's

Contents W. Callebaut/R. Riedl 2 Preface Donald T. Campbell 5 From Evolutionary Epistemology Via Selection Theory to a Sociology of Scientific Validity Linnda R. Caporael 39 Vehicles of Knowledge: Artifacts and Social Groups W. D. Christensen/C. A. Hooker 44 Selection Theory, Organization and the Development of Knowledge Andy J. Clark 49 Evolutionary Epistemology and the Scientific Method Ed Constant 55 Comments on Donald T. Campbell’s “From Evolutionary Epistemology Via Selection Theory to a Sociology of Scientific Validity” Steve Fuller 58 Campbell’s Failed Cultural Materialism Francis Heylighen 63 Objective, Subjective, and Intersubjective Selectors of Knowledge Aharon Kantorovich 68 The Rationality of Innovation and the Scientific Community as a Carrier of Knowledge Elias L. Khalil 71 Can Artificial Selection Remedy the Failing of Natural Section with Regard to Scientific Validation? Kyung-Man Kim 75 D. T. Campbell’s Social Epistemology of Science Marc De Mey 81 Vision as Paradigm: From VTE to Cognitive Science Erhard Oeser 85 The Two-stage Model of Evolutionary Epistemology Henry Plotkin 89 Knowledge and Adapted Biological Structures Massimo Stanzione 92 Campbell, Hayek and Kautsky on Societal Evolution Franz M. Wuketits 98 Four (or Five?) Types of Evolutionary Epistemology Evolution and Cognition: ISSN: 0938-2623 Published by: Konrad Lorenz Institut für Evolutions- und Kognitionsforschung, Adolf-Lorenz-Gasse 2, A-3422 Alten- Impressum berg/Donau. Tel.: 0043-2242-32390; Fax: 0043-2242-323904; e-mail: [email protected]; World Wide Web: http://www.kla.univie.ac.at/ Chairman: Ru- pert Riedl Managing Editor: Manfred Wimmer Layout: Alexander Riegler Aim and Scope: “Evolution and Cognition” is an interdisciplinary forum devoted to all aspects of research on cognition in animals and humans. -

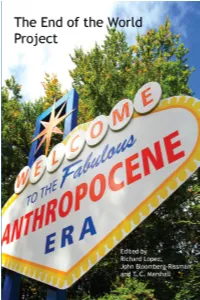

6X9 End of World Msalphabetical

THE END OF THE WORLD PROJECT Edited By RICHARD LOPEZ, JOHN BLOOMBERG-RISSMAN AND T.C. MARSHALL “Good friends we have had, oh good friends we’ve lost, along the way.” For Dale Pendell, Marthe Reed, and Sudan the white rhino TABLE OF CONTENTS Editors’ Trialogue xiii Overture: Anselm Hollo 25 Etel Adnan 27 Charles Alexander 29 Will Alexander 42 Will Alexander and Byron Baker 65 Rae Armantrout 73 John Armstrong 78 DJ Kirsten Angel Dust 82 Runa Bandyopadhyay 86 Alan Baker 94 Carlyle Baker 100 Nora Bateson 106 Tom Beckett 107 Melissa Benham 109 Steve Benson 115 Charles Bernstein 117 Anselm Berrigan 118 John Bloomberg-Rissman 119 Daniel Borzutzky 128 Daniel f Bradley 142 Helen Bridwell 151 Brandon Brown 157 David Buuck 161 Wendy Burk 180 Olivier Cadiot 198 Julie Carr / Lisa Olstein 201 Aileen Cassinetto and C. Sophia Ibardaloza 210 Tom Cohen 214 Claire Colebrook 236 Allison Cobb 248 Jon Cone 258 CA Conrad 264 Stephen Cope 267 Eduardo M. Corvera II (E.M.C. II) 269 Brenda Coultas 270 Anne Laure Coxam 271 Michael Cross 276 Thomas Rain Crowe 286 Brent Cunningham 297 Jane Dalrymple-Hollo 300 Philip Davenport 304 Michelle Detorie 312 John DeWitt 322 Diane Di Prima 326 Suzanne Doppelt 334 Paul Dresman 336 Aja Couchois Duncan 346 Camille Dungy 355 Marcella Durand 359 Martin Edmond 370 Sarah Tuss Efrik and Johannes Göransson 379 Tongo Eisen-Martin 397 Clayton Eshleman 404 Carrie Etter 407 Steven Farmer 409 Alec Finlay 421 Donna Fleischer 429 Evelyn Flores 432 Diane Gage 438 Jeannine Hall Gailey 442 Forrest Gander 448 Renée Gauthier 453 Crane Giamo 454 Giant Ibis 459 Alex Gildzen 460 Samantha Giles 461 C. -

Chauvet Cave: Man's First Masterpiece

ARDÈCHE CAVES few kilometres from the village of Vallon-Pont- So here I am, the last journalist to be allowed in before the d’Arc, the hub of the Gorges de l’Ardèche, lies gala opening in April. My minder is Élisabeth Cayrel, who put France’s most ambitious tourist project for decades together the proposal to have the Chauvet cave declared A– a €55 million replica of a prehistoric cave, a Unesco World Heritage site, a feat achieved in June 2014. painstakingly re-creating one of the most extraordinary finds of She has already given me the facts, the numbers and the gossip: our times. The architects Fabre-Speller wanted the building to how the name Caverne du Pont-d’Arc was chosen to distinguish be subsumed in the environment, which explains why, to reach the replica from the Grotte Chauvet after negotiations with it from the car park, I must stroll under the shade of green oaks Jean-Marie Chauvet to license his name broke down; how and saunter through wild boxwood bushes and juniper shrubs. a troop of chemists is re-creating the humidity and musty smell Like many great discoveries, chance played a big role. of the ancient sealed cave; or how a 3D scan has ensured that On 18 December, 1994, three cavers – Jean-Marie Chauvet, the geomorphology of the original has been fully reproduced. Éliette Brunel and Christian Hillaire – noticed a small cavity With a surface area of 3,500 square metres – around one-third 80 centimetres by 30 centimetres in the cliffs of the Cirque that of the real cave – and 439 reproductions out of the 450 d’Estre in the Ardèche département. -

1 Neural Connectivity of the Creative Mind Psyche Loui Setareh O'brien

Neural Connectivity of the Creative Mind Psyche Loui Setareh O’Brien Samuel Sontag Wesleyan University March 17, 2015 1 Abstract Human creativity contributes to the engagement, achievement, and subjective well-being of individuals. While historiometric and psychometric studies have defined multiple areas for creativity research, a neuroscientific understanding of how the human brain subserves creativity is only beginning to be realized. This chapter reviews the literature on the neuroscience of creativity, with special foci on how different components of creative cognition and domains of perception relate to the structural and functional connectivity of the human brain, and how these patterns of brain connectivity can inform interventions that foster creativity and innovation. Keywords Creativity, neuroimaging, structural connectivity, functional connectivity, creative cognition, perception, intervention 2 Introduction What would the world be like without creativity? Surely, the fundamentally human drive to create something wholly new and useful has catalyzed great achievements in history. Creativity contributes to the adaptation, growth, and pleasure of communities, and plays an important role in the well-being of individuals. Creativity can allow us to lose ourselves in engaging activities, to achieve success by developing innovative solutions to problems, and to make social contributions that provide satisfaction and meaning in our lives. These ends—engagement, achievement, and meaning—are considered to be among the key components of the flourishing life (Seligman 2011). More specifically, research studies suggest that creativity may be positively correlated with measures of happiness and subjective well-being (Pannells & Claxton, 2008; Tamannaeifar & Motaghedifard, 2014). As positive psychology embraces the use of scientific inquiry to increase happiness and improve well-being, the movement would be incomplete without a thorough investigation of this core human strength (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Simonton, 2002).