Cave of Forgotten Dreams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art in the Stone Age Terminology

Art in the Stone Age Terminology ● Paleolithic- (Greek) ○ Paleo-Old ○ Lithos-Stone. ○ 40,000-9,000BCE ○ Characteristics, Hunter Gatherer, Caves. Migration ● Mesolithic, ○ Meso-Middle ○ Lithos- Stone Age ○ 10,000-5,000 bce ○ Characteristics, Beginnings of Cities, Dog Domestication, Transition to agricultural and animal domestication ● Neolithic, ○ Neo-New ○ Lithos-Stone ○ 8,000-2300 BCE ○ Development of Cities, Animal Husbandry Herding, Agriculture, People Began to stay in one place Mistakes in Art History The saying Goes.. “History is Written by the victors.” Niccolo Machiavelli Mercator Map Projection. https://youtu.be/KUF_Ckv8HbE http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo- way/2016/01/21/463835225/discovery-of- ancient-massacre-suggests-war-predated- settlements Radio Carbon Dating https://youtu.be/54e5Bz7m3do A process Archaeologists use among others to estimate how long ago an artifact was made. Makapansgat Face Pebble resembling a face, Makapansgat, ca. 3,000,000 bce. This pebble of one of the earliest examples of representation of the human form. Apollo 11 Cave Animal facing left, from the Apollo 11 Cave, Namibia, ca. 23,000bce. Charcoal on stone, 5”x4.25”. State Museum of Namibia, Windhoek. Scientists between 1969-1972 scientists working in the Apollo 11 Cave in Namibia found seven fragments of painted stone plaques, transportable. The approximate date of the charcoal from the archeological layer containing the Namibian plaques is 23,000bce. Hohlenstein-Stadel Human with feline (Lion?) head, from Hohlenstein-Stadel Germany, ca 40,000- 35,000BCE Appox 12” in length this artifact was carved from ivory from a mammoth tusk This object was originally thought to be of 30,000bce, was pushed back in time due to additional artifacts found later on the same excavation layer. -

The Janus-Faced Dilemma of Rock Art Heritage

The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion Mélanie Duval, Christophe Gauchon To cite this version: Mélanie Duval, Christophe Gauchon. The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, Taylor & Francis, In press, 10.1080/13505033.2020.1860329. hal-03078965 HAL Id: hal-03078965 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03078965 Submitted on 21 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Duval Mélanie, Gauchon Christophe, 2021. The Janus-faced dilemma of rock art heritage management in Europe: a double dialectic process between conservation and public outreach, transmission and exclusion, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, doi.org/10.1080/13505033.2020.1860329 Authors: Mélanie Duval and Christophe Gauchon Mélanie Duval: *Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA), Université Savoie Mont Blanc (USMB), CNRS, Environnements, Dynamics and Territories of Mountains (EDYTEM), Chambéry, France; * Rock Art Research Institute GAES, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. Christophe Gauchon: *Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA), Université Savoie Mont Blanc (USMB), CNRS, Environnements, Dynamics and Territories of Mountains (EDYTEM), Chambéry, France. -

December 2010

International I F L A Preservation PP AA CC o A Newsletter of the IFLA Core Activity N . 52 News on Preservation and Conservation December 2010 Tourism and Preservation: Some Challenges INTERNATIONAL PRESERVATION Tourism and Preservation: No 52 NEWS December 2010 Some Challenges ISSN 0890 - 4960 International Preservation News is a publication of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) Core 6 Activity on Preservation and Conservation (PAC) The Economy of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Conservation that reports on the preservation Valéry Patin activities and events that support efforts to preserve materials in the world’s libraries and archives. 12 IFLA-PAC Bibliothèque nationale de France Risks Generated by Tourism in an Environment Quai François-Mauriac with Cultural Heritage Assets 75706 Paris cedex 13 France Miloš Drdácký and Tomáš Drdácký Director: Christiane Baryla 18 Tel: ++ 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 70 Fax: ++ 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 80 Cultural Heritage and Tourism: E-mail: [email protected] A Complex Management Combination Editor / Translator Flore Izart The Example of Mauritania Tel: ++ 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 71 Jean-Marie Arnoult E-mail: fl [email protected] Spanish Translator: Solange Hernandez Layout and printing: STIPA, Montreuil 24 PAC Newsletter is published free of charge three times a year. Orders, address changes and all The Challenge of Exhibiting Dead Sea Scrolls: other inquiries should be sent to the Regional Story of the BnF Exhibition on Qumrân Manuscripts Centre that covers your area. 3 See -

Abstracts of Reports and Posters

Abstracts of Reports and Posters Amira Adaileh The Magdalenian site of Bad Kösen-Lengefeld The open air site of Bad Kösen-Lengefeld is located in Sachsen-Anhalt, Eastern Germany. It was discov- ered in the mid 1950´s in the immediate vicinity of the famous Magdalenian site of Saaleck. Since that time, archaeologists collected over 2000 lithic artifacts during systematical surveys. The technological and typological analyses of the lithic artifacts confirmed the assignment of Bad Kösen-Lengefeld to a late Magdalenian. Furthermore, the investigation of the surface collections brought forward information about the character of this camp site, the duration of its occupation and the pattern of raw material procure- ment. The fact that Bad Kösen-Lengefeld is located in a region with more than 100 Magdalenian sites fostered a comparison of the lithic inventory with other Magdalenian assemblages. Thus, allowing to spec- ify the position of the Lengefeld collection within the chorological context of the Magdalenian in Eastern Germany. Jehanne Affolter, Ludovic Mevel Raw material circulation in northern french alps and Jura during lateglacial interstadial : method, new data and paleohistoric implication Since fifteen years the study of the characterization and origin of flint resources used by Magdalenian and Azilian groups in northern French Alps and Jura have received significant research work. Diverse and well distributed spatially, some of these resources were used and disseminated throughout the late Upper Paleolithic. Which changes do we observe during the Magdalenian then for the Azilian? The results of petrographic analysis and techno-economic analysis to several archaeological sites allow us to assess dia- chronic changes in economic behavior of these people and discuss the significance of these results. -

'Large-Scale Mitogenomic Analysis

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2019 Large-scale mitogenomic analysis of the phylogeography of the Late Pleistocene cave bear Gretzinger, Joscha ; Molak, Martyna ; Reiter, Ella ; Pfrengle, Saskia ; Urban, Christian ; Neukamm, Judith ; Blant, Michel ; Conard, Nicholas J ; Cupillard, Christophe ; Dimitrijević, Vesna ; Drucker, Dorothée G ; Hofman-Kamińska, Emilia ; Kowalczyk, Rafał ; Krajcarz, Maciej T ; Krajcarz, Magdalena ; Münzel, Susanne C ; Peresani, Marco ; Romandini, Matteo ; Rufí, Isaac ; Soler, Joaquim ; Terlato, Gabriele ; Krause, Johannes ; Bocherens, Hervé ; Schuenemann, Verena J Abstract: The cave bear (Ursus spelaeus) is one of the Late Pleistocene megafauna species that faced extinction at the end of the last ice age. Although it is represented by one of the largest fossil records in Europe and has been subject to several interdisciplinary studies including palaeogenetic research, its fate remains highly controversial. Here, we used a combination of hybridisation capture and next generation sequencing to reconstruct 59 new complete cave bear mitochondrial genomes (mtDNA) from 14 sites in Western, Central and Eastern Europe. In a Bayesian phylogenetic analysis, we compared them to 64 published cave bear mtDNA sequences to reconstruct the population dynamics and phylogeography dur- ing the Late Pleistocene. We found five major mitochondrial DNA lineages resulting in a noticeably more complex biogeography of the European lineages during the last 50,000 years than previously assumed. Furthermore, our calculated effective female population sizes suggest a drastic cave bear population de- cline starting around 40,000 years ago at the onset of the Aurignacian, coinciding with the spread of anatomically modern humans in Europe. -

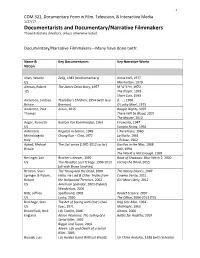

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

Dating Aurignacian Rock Art in Altxerri B Cave (Northern Spain)

Journal of Human Evolution 65 (2013) 457e464 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol Not only Chauvet: Dating Aurignacian rock art in Altxerri B Cave (northern Spain) C. González-Sainz a, A. Ruiz-Redondo a,*, D. Garate-Maidagan b, E. Iriarte-Avilés c a Instituto Internacional de Investigaciones Prehistóricas de Cantabria (IIIPC), Avenida de los Castros s/n, 39005 Santander, Spain b CREAP Cartailhac-TRACES-UMR 5608, University de Toulouse-Le Mirail, 5 allées Antonio Machado, 31058 Toulouse Cedex 9, France c Laboratorio de Evolución Humana, Dpto. CC. Históricas y Geografía, University de Burgos, Plaza de Misael Bañuelos s/n, Edificio IþDþi, 09001 Burgos, Spain article info abstract Article history: The discovery and first dates of the paintings in Grotte Chauvet provoked a new debate on the origin and Received 29 May 2013 characteristics of the first figurative Palaeolithic art. Since then, other art ensembles in France and Italy Accepted 2 August 2013 (Aldène, Fumane, Arcy-sur-Cure and Castanet) have enlarged our knowledge of graphic activity in the early Available online 3 September 2013 Upper Palaeolithic. This paper presents a chronological assessment of the Palaeolithic parietal ensemble in Altxerri B (northern Spain). When the study began in 2011, one of our main objectives was to determine the Keywords: age of this pictorial phase in the cave. Archaeological, geological and stylistic evidence, together with Upper Palaeolithic radiometric dates, suggest an Aurignacian chronology for this art. The ensemble in Altxerri B can therefore Radiocarbon dating Cantabrian region be added to the small but growing number of sites dated in this period, corroborating the hypothesis of fi Cave painting more complex and varied gurative art than had been supposed in the early Upper Palaeolithic. -

Musical Origins and the Stone Age Evolution of Flutes

Musical Origins and the Stone Age Evolution of Flutes When we, modern humans, emerged from Africa and colonized Europe Jelle Atema 45,000 years ago, did we have flutes in fist and melodies in mind? Email: [email protected] Introduction Music is an intensely emotional subject and the origins of music have fascinated Postal: people for millennia, going back to early historic records. An excellent review can Boston University be found in “Dolmetsch Online” (http://www.dolmetsch.com/musictheory35. Biology Department htm). Intense debates in the late 19th and early 20th century revolved around the 5 Cummington Street origins of speech and music and which came first. Biologist Charles Darwin, befit- Boston, MA 02215 ting his important recognition of evolution by sexual selection, considered that music evolved as a courtship display similar to bird song; he also felt that speech derived from music. Musicologist Spencer posited that music derived from the emotional content of human speech. The Darwin–Spencer debate (Kivy, 1959) continues unresolved. During the same period the eminent physicist Helmholtz- following Aristotle-studied harmonics of sound and felt that music distinguished itself from speech by its “fixed degree in the scale” (Scala = stairs, i.e. discrete steps) as opposed to the sliding pitches (“glissando”) typical of human speech. As we will see, this may not be such a good distinction when analyzing very early musi- cal instruments with our contemporary bias toward scales. More recent symposia include “The origins of music” (Wallin et al., 2000) and “The music of nature and the nature of music” (Gray et al., 2001). -

KMBT C554e-20150630165533

Recent Research on Paleolithic Arts in Europe and the Multimedia Database Cesar Gonzalez Sai 民 Roberto Cacho Toca Department Department of Historical Sciences. University of Cantabria. Avda. Los Castros s/n. 39005. SANTANDER (Spain) e-mail: e-mail: [email protected] I [email protected] Summary. In In this article the authors present the Multimedia Photo YR Database, made by Texnai, Inc. (Tokyo) and the the Department of Historical Sciences of the University of Cantabria (Spain) about the paleolithic art in northern northern Spain. For this purpose, it ’s made a short introduction to the modem knowledge about the European European paleolithic art (35000 ・1 1500 BP), giving special attention to the last research trends and, in which way, the new techniques (computers, digital imaging, database, physics ... ) are now improving the knowledge about this artistic works. Finally, is made a short explanation about the Multimedia Photo YR Database Database and in which way, these databases can improve, not only research and teaching, but also it can promote in the authorities and people the convenience of an adequate conservation and research of these artistic artistic works. Key Words: Multimedia Database, Paleolithic Art, Europe, North Spain, Research. 1. 1. Introduction. The paleolithic European art. Between approximately 35000 and 11500 years BP, during the last glacial phases, the European continent continent saw to be born a first artistic cycle of surprising surprising aesthetic achievements. The expressive force force reached in the representation of a great variety of of wild animals, with some very simple techniques, techniques, has been rarely reached in the history of the the western a此 We find this figurative art in caves, caves, rock-shelters and sites in the open air, and at the the same time, on very di 仔erent objects of the daily li た (pendants, spatulas, points ofjavelin, harpoons, perforated perforated baton, estatues or simple stone plates). -

Homo Aestheticus’

Conceptual Paper Glob J Arch & Anthropol Volume 11 Issue 3 - June 2020 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Shuchi Srivastava DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2020.11.555815 Man and Artistic Expression: Emergence of ‘Homo Aestheticus’ Shuchi Srivastava* Department of Anthropology, National Post Graduate College, University of Lucknow, India Submission: May 30, 2020; Published: June 16, 2020 *Corresponding author: Shuchi Srivastava, Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, National Post Graduate College, An Autonomous College of University of Lucknow, Lucknow, India Abstract Man is a member of animal kingdom like all other animals but his unique feature is culture. Cultural activities involve art and artistic expressions which are the earliest methods of emotional manifestation through sign. The present paper deals with the origin of the artistic expression of the man, i.e. the emergence of ‘Homo aestheticus’ and discussed various related aspects. It is basically a conceptual paper; history of art begins with humanity. In his artistic instincts and attainments, man expressed his vigour, his ability to establish a gainful and optimistictherefore, mainlyrelationship the secondary with his environmentsources of data to humanizehave been nature. used for Their the behaviorsstudy. Overall as artists findings was reveal one of that the man selection is artistic characteristics by nature suitableand the for the progress of the human species. Evidence from extensive analysis of cave art and home art suggests that humans have also been ‘Homo aestheticus’ since their origins. Keywords: Man; Art; Artistic expression; Homo aestheticus; Prehistoric art; Palaeolithic art; Cave art; Home art Introduction ‘Sahityasangeetkalavihinah, Sakshatpashuh Maybe it was the time when some African apelike creatures to 7 million years ago, the first human ancestors were appeared. -

Sorting the Ibex from the Goats in Portugal Robert G

Sorting the ibex from the goats in Portugal Robert G. Bednarik An article by António Martinho Baptista (2000) in the light-weight rock art magazine Adoranten1 raises a number of fascinating issues about taxonomy. The archaeological explanations so far offered for a series of rock art sites in the Douro basin of northern Portugal and adjacent parts of Spain contrast with the scientific evidence secured to date from these sites. This includes especially archaeozoological, geomorphological, sedimentary, palaeontological, dating and especially analytical data from the art itself. For instance one of the key arguments in favour of a Pleistocene age of fauna depicted along the Côa is the claim that ibex became extinct in the region with the end of the Pleistocene. This is obviously false. Not only do ibex still occur in the mountains of the Douro basin—even if their numbers have been decimated—they existed there throughout the Holocene. More relevantly, the German achaeozoologist T. W. Wyrwoll (2000) has pointed out that all the ibex-like figures in the Côa valley resemble Capra ibex lusitanica or victoriae. The Portuguese ibex, C. i. lusitanica, became extinct only in 1892, and not as Zilhão (1995) implies at the end of the Pleistocene. The Gredos ibex (C. i. victoriae) still survives in the region. The body markings depicted on one of the Côa zoomorphs, a figure from Rego da Vide, resemble those found on C. i. victoriae so closely that this typical Holocene sub-species rather than a Pleistocene sub-species (notably Capra ibex pyrenaica) is almost certainly depicted (Figure 1). -

|||GET||| Introduction to Human Evolution a Bio-Cultural Approach

INTRODUCTION TO HUMAN EVOLUTION A BIO- CULTURAL APPROACH (FIRST EDITION) 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Gillian Crane-Kramer | 9781631898662 | | | | | The Biocultural Evolution Blog See Article History. Viewed zoologically, we humans are Homo sapiensa culture-bearing upright-walking species that lives on the ground and very likely first evolved in Africa aboutyears ago. See also: Evolution of primates. The ulnar opposition—the contact between the thumb and the tip of the little finger of the same hand—is unique to the genus Homo[53] including Neanderthals, the Sima de los Huesos hominins and anatomically modern humans. The biocultural-feedback concept helps us to place this finding in a bigger framework of human evolution. This, coupled with pathological dwarfism, could have resulted in a significantly diminutive human. Add to cart. In Africa in the Early Pleistocene, 1. August 22, Retrieved The main find was a skeleton believed to be a woman of about 30 years Introduction to Human Evolution A Bio-Cultural Approach (First Edition) 1st edition age. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. In devising such scenarios and filling in the human family bush, researchers must consult a large and diverse array of fossils, and they must also employ refined excavation methods and records, geochemical dating techniques, and data from other specialized fields such as geneticsecology and paleoecology, and ethology animal behaviour —in short, all the tools of the multidisciplinary science of paleoanthropology. An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy. It is also possible that one or more of these species are ancestors of another branch of African apes, or that they represent a shared ancestor between hominins and other apes.