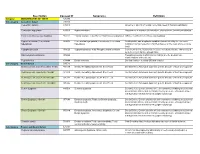

Nasopharyngeal Tube – Clinical Practice Guideline EVIDENCE TABLE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Primary Care Pediatrician and the Care of Children with Cleft Lip And/Or Cleft Palate Charlotte W

CLINICAL REPORT Guidance for the Clinician in Rendering Pediatric Care The Primary Care Pediatrician Charlotte W. Lewis, MD, MPH, FAAP, a Lisa S. Jacob, DDS, MS, b Christoph U. andLehmann, MD, the FAAP, FACMI, Care c SECTION ON ORALof HEALTH Children With Cleft Lip and/or Cleft Palate Orofacial clefts, specifically cleft lip and/or cleft palate (CL/P), are among the abstract most common congenital anomalies. CL/P vary in their location and severity and comprise 3 overarching groups: cleft lip (CL), cleft lip with cleft palate (CLP), and cleft palate alone (CP). CL/P may be associated with one of many syndromes that could further complicate a child’s needs. Care of patients aDivision of General Pediatrics and Hospital Medicine, Department of with CL/P spans prenatal diagnosis into adulthood. The appropriate timing Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine and Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, Washington; bGeorgetown Pediatric and order of specific cleft-related care are important factors for optimizing Dentistry and Orthodontics, Georgetown, Texas; and Departments of cBiomedical Informatics and Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University Medical outcomes; however, care should be individualized to meet the specific needs Center, Nashville, Tennessee of each patient and family. Children with CL/P should receive their specialty All three authors participated extensively in developing, researching, cleft-related care from a multidisciplinary cleft or craniofacial team with and writing the manuscript and revising it based on reviewers’ comments; Dr Lehmann made additional revisions after review by the sufficient patient and surgical volume to promote successful outcomes. board of directors. The primary care pediatrician at the child’s medical home has an essential This document is copyrighted and is property of the American role in making a timely diagnosis and referral; providing ongoing health Academy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors. -

Soonerstart Automatic Qualifying Syndromes and Conditions 001

SoonerStart Automatic Qualifying Syndromes and Conditions 001 Abetalipoproteinemia 272.5 002 Acanthocytosis (see Abetalipoproteinemia) 272.5 003 Accutane, Fetal Effects of (see Fetal Retinoid Syndrome) 760.79 004 Acidemia, 2-Oxoglutaric 276.2 005 Acidemia, Glutaric I 277.8 006 Acidemia, Isovaleric 277.8 007 Acidemia, Methylmalonic 277.8 008 Acidemia, Propionic 277.8 009 Aciduria, 3-Methylglutaconic Type II 277.8 010 Aciduria, Argininosuccinic 270.6 011 Acoustic-Cervico-Oculo Syndrome (see Cervico-Oculo-Acoustic Syndrome) 759.89 012 Acrocephalopolysyndactyly Type II 759.89 013 Acrocephalosyndactyly Type I 755.55 014 Acrodysostosis 759.89 015 Acrofacial Dysostosis, Nager Type 756.0 016 Adams-Oliver Syndrome (see Limb and Scalp Defects, Adams-Oliver Type) 759.89 017 Adrenoleukodystrophy, Neonatal (see Cerebro-Hepato-Renal Syndrome) 759.89 018 Aglossia Congenita (see Hypoglossia-Hypodactylia) 759.89 019 Albinism, Ocular (includes Autosomal Recessive Type) 759.89 020 Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Brown Type (Type IV) 759.89 021 Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Tyrosinase Negative (Type IA) 759.89 022 Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Tyrosinase Positive (Type II) 759.89 023 Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Yellow Mutant (Type IB) 759.89 024 Albinism-Black Locks-Deafness 759.89 025 Albright Hereditary Osteodystrophy (see Parathyroid Hormone Resistance) 759.89 026 Alexander Disease 759.89 027 Alopecia - Mental Retardation 759.89 028 Alpers Disease 759.89 029 Alpha 1,4 - Glucosidase Deficiency (see Glycogenosis, Type IIA) 271.0 030 Alpha-L-Fucosidase Deficiency (see Fucosidosis) -

Research Article

z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 10, Issue, 07, pp.71222-71228, July, 2018 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE THE TONGUE SPEAKS A LOT OF HEALTH. 1,*Dr. Firdous Shaikh, 2Dr. Sonia Sodhi, 3Dr Zeenat Fatema Farooqui and 4Dr. Lata Kale 1PG Student, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, CSMSS Dental College and Hospital, Aurangabad 2Professor, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, CSMSS Dental College and Hospital, Aurangabad 3Fatema Farooqui, Chief Medical Officer, Sri Ram Homeopathic Clinic and Research Center, Solapur 4Professor and Head, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, CSMSS Dental College and Hospital, Aurangabad ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: Multifunctional organ of the human body without a bone yet strong is the tongue. It mainly consists Received 26th April, 2018 of the functional portion of muscle mass, mucosa, fat and the specialized tissue of taste i.e. the Received in revised form papillae. Diseases may either result from internal/ systemic causes of extrinsic causes like trauma, 14th May, 2018 infection, etc. A new method for classification has been proposed in this review for diseases of Accepted 09th June, 2018 tongue. This review mainly focuses on encompassing almost each aspect that the body reflects via its th Published online 30 July, 2018 mirror in mouth, the tongue. Key Words: Tongue, Diseases of Tongue, Discoloration of Tongue, Oral health, Hairy Tongue. Copyright © 2018, Firdous Shaikh et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Oral Health Abnormalities in Children Born with Macrosomia Established During Mixed Dentition Period

© Wydawnictwo Aluna Wiadomości Lekarskie 2019, tom LXXII, nr 5 cz I PRACA ORYGINALNA ORIGINAL ARTICLE ORAL HEALTH ABNORMALITIES IN CHILDREN BORN WITH MACROSOMIA ESTABLISHED DURING MIXED DENTITION PERIOD Olga V. Garmash KHARKIV NATIONAL MEDICAL UNIVERSITY, KHARKIV, UKRAINE ABSTRACT Introduction: The prevalence of soft tissue and hard tooth tissuediseases in the oral cavity and the morphofunctional disorders of craniofacial complex, require attention ofspecialistsin various branches of medicine. Scientists began to pay attention to metabolic and other violations that have occurred in the fetal development and led to the occurrence of certain changes in the dental status of the child. The aim of thisresearch is to study the features of the dental health condition in the children of Northeast of Ukraine, who were born with macrosomia during the period of mixed dentition. The study takes into account intrauterine body length growth acceleration, intrauterine obesity or well-balanced acceleration of both the body weight and length gain. Materials and methods: Thirty 6.5–11-year-old children with fetal macrosomia were examined (MainGroup). A Comparison Group was comprised of sixteen children, whose weight-height parameters at birth were normal (fetal normosomia). All children in the Main group were split into four subgroups in accordance with weight-height parameters at birth using the V. I. Grischenko and his co-authors’ harmonious coefficient. The evaluation of the hygiene status of the oral cavity, the dental caries intensity evaluation, and the quantitative analysis of minor salivary gland secretion have been performed. The prevalence of dentoalveolar abnormalities was evaluated. Results: The highest values of caries intensity were recorded in macrosomic-at-birth children born with harmonious (well-balanced) intrauterine development, with intrauterine obesity and increased body length, or with intrauterine obesity and an average body length. -

Lieshout Van Lieshout, M.J.S

EXPLORING ROBIN SEQUENCE Manouk van Lieshout Van Lieshout, M.J.S. ‘Exploring Robin Sequence’ Cover design: Iliana Boshoven-Gkini - www.agilecolor.com Thesis layout and printing by: Ridderprint BV - www.ridderprint.nl ISBN: 978-94-6299-693-9 Printing of this thesis has been financially supported by the Erasmus University Rotterdam. Copyright © M.J.S. van Lieshout, 2017, Rotterdam, the Netherlands All rights reserved. No parts of this thesis may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission of the author or when appropriate, the corresponding journals Exploring Robin Sequence Verkenning van Robin Sequentie Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnificus Prof.dr. H.A.P. Pols en volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties. De openbare verdediging zal plaatsvinden op woensdag 20 september 2017 om 09.30 uur door Manouk Ji Sook van Lieshout geboren te Seoul, Korea PROMOTIECOMMISSIE Promotoren: Prof.dr. E.B. Wolvius Prof.dr. I.M.J. Mathijssen Overige leden: Prof.dr. J.de Lange Prof.dr. M. De Hoog Prof.dr. R.J. Baatenburg de Jong Copromotoren: Dr. K.F.M. Joosten Dr. M.J. Koudstaal TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Chapter I: General introduction 9 Chapter II: Robin Sequence, A European survey on current 37 practice patterns Chapter III: Non-surgical and surgical interventions for airway 55 obstruction in children with Robin Sequence AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION Chapter IV: Unravelling Robin Sequence: Considerations 79 of diagnosis and treatment Chapter V: Management and outcomes of obstructive sleep 95 apnea in children with Robin Sequence, a cross-sectional study Chapter VI: Respiratory distress following palatal closure 111 in children with Robin Sequence QUALITY OF LIFE Chapter VII: Quality of life in children with Robin Sequence 129 GENERAL DISCUSSION AND SUMMARY Chapter VIII: General discussion 149 Chapter IX: Summary / Nederlandse samenvatting 169 APPENDICES About the author 181 List of publications 183 Ph.D. -

Plastic Surgery Essentials for Students Handbook to All Third Year Medical Students Concerned with the Effect of the Outcome on the Entire Patient

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PLASTIC SURGEONS YOUNG PLASTIC SURGEONS STEERING COMMITTEE Lynn Jeffers, MD, Chair C. Bob Basu, MD, Vice Chair Eighth Edition 2012 Essentials for Students Workgroup Lynn Jeffers, MD Adam Ravin, MD Sami Khan, MD Chad Tattini, MD Patrick Garvey, MD Hatem Abou-Sayed, MD Raman Mahabir, MD Alexander Spiess, MD Howard Wang, MD Robert Whitfield, MD Andrew Chen, MD Anureet Bajaj, MD Chris Zochowski, MD UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION COMMITTEE OF THE PLASTIC SURGERY EDUCATIONAL FOUNDATION First Edition 1979 Ruedi P. Gingrass, MD, Chairman Martin C. Robson, MD Lewis W.Thompson, MD John E.Woods, MD Elvin G. Zook, MD Copyright © 2012 by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons 444 East Algonquin Road Arlington Heights, IL 60005 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-9859672-0-8 i INTRODUCTION PREFACE This book has been written primarily for medical students, with constant attention to the thought, A CAREER IN PLASTIC SURGERY “Is this something a student should know when he or she finishes medical school?” It is not designed to be a comprehensive text, but rather an outline that can be read in the limited time Originally derived from the Greek “plastikos” meaning to mold and reshape, plastic surgery is a available in a burgeoning curriculum. It is designed to be read from beginning to end. Plastic specialty which adapts surgical principles and thought processes to the unique needs of each surgery had its beginning thousands of years ago, when clever surgeons in India reconstructed individual patient by remolding, reshaping and manipulating bone, cartilage and all soft tissues. -

2016-Chapter-143-Oropharyngeal-Growth-And-Malformations-PPSM-6E-1.Pdf

To protect the rights of the author(s) and publisher we inform you that this PDF is an uncorrected proof for internal business use only by the author(s), editor(s), reviewer(s), Elsevier and typesetter Toppan Best-set. It is not allowed to publish this proof online or in print. This proof copy is the copyright property of the publisher and is confidential until formal publication. Chapter c00143 Oropharyngeal Growth and Skeletal Malformations 143 Stacey Dagmar Quo; Benjamin T. Pliska; Nelly Huynh Chapter Highlights p0010 • Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) is marked by manifestations has not been determined. The varying degrees of collapsibility of the length and volume of the airway increase until pharyngeal airway. The hard tissue boundaries the age of 20 years, at which time there is a of the airway dictate the size and therefore the variable period of stability, followed by a slow responsiveness of the muscles that form this decrease in airway size after the fifth decade of part of the upper airway. Thus, the airway is life. The possibility of addressing the early forms shaped not only by the performance of the of this disease with the notions of intervention pharyngeal muscles to stimulation but also by and prevention can change the landscape the surrounding skeletal framework. of care. u0015 • The upper and lower jaws are key components • Correction of specific skeletal anatomic u0025 of the craniofacial skeleton and the deficiencies can improve or eliminate SDB determinants of the anterior wall of the upper symptoms in both children and adults. It is airway. The morphology of the jaws can be possible that the clinician may adapt or modify negatively altered by dysfunction of the upper the growth expression, although the extent of airway during growth and development. -

Abstracts of the XXI Brazilian Congress of Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology

Vol. 117 No. 2 February 2014 Abstracts of the XXI Brazilian Congress of Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology ORAL PRESENTATIONS GERMANO, MÁRCIA CRISTINA DA COSTA MIGUEL, ÉRICKA JANINE DANTAS DA SILVEIRA. UNIVERSIDADE AO-01 - MAXILLARY OSTEOSARCOMA INITIALLY FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE. RESEMBLING PERIAPEX DENTAL INJURY: CLINICAL Renal osteodystrophy represents the musculoskeletal mani- CASE REPORT. JOANA DOURADO MARTINS, JARIELLE festations resulting from metabolic abnormalities in patients with OLIVEIRA MASCARENHAS ANDRADE, JULIANA ARAUJO chronic renal failure (CRF). Woman, 23, reported a hard, asymp- LIMA DA SILVA, ALESSANDRA LAIS PINHO VALENTE, tomatic, expansive mass present for 4 years on the right side of the MÁRCIO CAMPOS OLIVEIRA, MICHELLE MIRANDA face that was causing airway compromise and facial disfigurement. LOPES FALCÃO, VALÉRIA SOUZA FREITAS. UNI- Her history included idiopathic CRF, and she had been receiving VERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE FEIRA DE SANTANA. hemodialysis for 10 years. During this period she developed sec- Maxillary osteosarcoma is a rare and aggressive bone tumor ondary hyperparathyroidism that was managed with total para- that can initially resemble a periapical lesion. Man, 42, came to the thyroidectomy. Computed tomography revealed marked osseous Oral Lesions Reference Center at UEFS complaining of “tooth expansion on the right side of the maxilla and discrete expansion numbness and swollen gums” and loss of sensation in the anterior on the right side of mandible and cranial base. The clinical diag- teeth. His history included previous endodontic emergency treat- nosis was brown tumor. Incisional biopsy led to a diagnosis of ment of units 1.1 and 2.1. The extraoral examination demonstrated renal osteodystrophy. -

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition Category ABNORMALITIES OF TEETH 426390 Subcategory Cementum Defect 399115 Cementum aplasia 346218 Absence or paucity of cellular cementum (seen in hypophosphatasia) Cementum hypoplasia 180000 Hypocementosis Disturbance in structure of cementum, often seen in Juvenile periodontitis Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia 958771 Familial multiple cementoma; Florid osseous dysplasia Diffuse, multifocal cementosseous dysplasia Hypercementosis (Cementation 901056 Cementation hyperplasia; Cementosis; Cementum An idiopathic, non-neoplastic condition characterized by the excessive hyperplasia) hyperplasia buildup of normal cementum (calcified tissue) on the roots of one or more teeth Hypophosphatasia 976620 Hypophosphatasia mild; Phosphoethanol-aminuria Cementum defect; Autosomal recessive hereditary disease characterized by deficiency of alkaline phosphatase Odontohypophosphatasia 976622 Hypophosphatasia in which dental findings are the predominant manifestations of the disease Pulp sclerosis 179199 Dentin sclerosis Dentinal reaction to aging OR mild irritation Subcategory Dentin Defect 515523 Dentinogenesis imperfecta (Shell Teeth) 856459 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield I 977473 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield II 976722 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; -

EUROCAT Syndrome Guide

JRC - Central Registry european surveillance of congenital anomalies EUROCAT Syndrome Guide Definition and Coding of Syndromes Version July 2017 Revised in 2016 by Ingeborg Barisic, approved by the Coding & Classification Committee in 2017: Ester Garne, Diana Wellesley, David Tucker, Jorieke Bergman and Ingeborg Barisic Revised 2008 by Ingeborg Barisic, Helen Dolk and Ester Garne and discussed and approved by the Coding & Classification Committee 2008: Elisa Calzolari, Diana Wellesley, David Tucker, Ingeborg Barisic, Ester Garne The list of syndromes contained in the previous EUROCAT “Guide to the Coding of Eponyms and Syndromes” (Josephine Weatherall, 1979) was revised by Ingeborg Barisic, Helen Dolk, Ester Garne, Claude Stoll and Diana Wellesley at a meeting in London in November 2003. Approved by the members EUROCAT Coding & Classification Committee 2004: Ingeborg Barisic, Elisa Calzolari, Ester Garne, Annukka Ritvanen, Claude Stoll, Diana Wellesley 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Definitions 6 Coding Notes and Explanation of Guide 10 List of conditions to be coded in the syndrome field 13 List of conditions which should not be coded as syndromes 14 Syndromes – monogenic or unknown etiology Aarskog syndrome 18 Acrocephalopolysyndactyly (all types) 19 Alagille syndrome 20 Alport syndrome 21 Angelman syndrome 22 Aniridia-Wilms tumor syndrome, WAGR 23 Apert syndrome 24 Bardet-Biedl syndrome 25 Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (EMG syndrome) 26 Blepharophimosis-ptosis syndrome 28 Branchiootorenal syndrome (Melnick-Fraser syndrome) 29 CHARGE -

Developmental Disorders of the Dentition: an Update OPHIR D

American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C (Seminars in Medical Genetics) 163C:318–332 (2013) ARTICLE Developmental Disorders of the Dentition: An Update OPHIR D. KLEIN, SNEHLATA OBEROI, ANN HUYSSEUNE, MARIA HOVORAKOVA, MIROSLAV PETERKA, AND RENATA PETERKOVA Dental anomalies are common congenital malformations that can occur either as isolated findings or as part of a syndrome. This review focuses on genetic causes of abnormal tooth development and the implications of these abnormalities for clinical care. As an introduction, we describe general insights into the genetics of tooth development obtained from mouse and zebrafish models. This is followed by a discussion of isolated as well as syndromic tooth agenesis, including Van der Woude syndrome (VWS), ectodermal dysplasias (EDs), oral‐facial‐ digital (OFD) syndrome type I, Rieger syndrome, holoprosencephaly, and tooth anomalies associated with cleft lip and palate. Next, we review delayed formation and eruption of teeth, as well as abnormalities in tooth size, shape, and form. Finally, isolated and syndromic causes of supernumerary teeth are considered, including cleidocranial dysplasia and Gardner syndrome. © 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. KEY WORDS: mouse; zebrafish; teeth; hypodontia; supernumerary teeth; craniofacial; syndrome How to cite this article: Klein OD, Oberoi S, Huysseune A, Hovorakova M, Peterka M, Peterkova R. 2013. Developmental disorders of the dentition: An update. Am J Med Genet Part C Semin Med Genet 163C:318–332. INTRODUCTION with craniofacial developmental abnor- diagnostic findings in a number of Genetic causes have been identified for malities. Congenitally missing teeth syndromes. Additionally, mutations in both isolated tooth malformations and are seen in a host of syndromes, and several genes have been associated with for the dental anomalies seen in patients supernumerary teeth are also central both hypodontia and orofacial clefting Grant sponsor: NIH; Grant numbers: DP2‐OD00719, R01‐DE021420. -

Bbm:978-1-4614-8681-7/1.Pdf

Index A Babygram , 86 ABO incompatibility , 70 Balanitis , 65 Absence seizures , 16 Balanoposthitis , 66 Abstract reasoning , 19 Barotrauma , 111 Acrocyanosis , 40 Beckwith’s syndrome , 86 ADD. See Attention-defi cit disorder (ADD) Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome , 44, 75 ADHD. See Attention-defi cit hyperactivity Bilateral ankle clonus , 40 disorder (ADHD) Bilateral cryptorchidism , 33 Adrenal hyperplasia , 32 Biliary atresia , 39 Adrenal insuffi ciency , 36 Bili levels , 46 Alpha fetoprotein (AFP) , 45 Bilirubin , 48 Anatomical/obstructive problems , 38 Biophysical profi le , 45 Androgen insensitivity syndrome , 32 Birth hypoxia , 41 Androgen receptors , 32 Birth-related clavicle fracture , 45 Androgens , 32 Birth weight , 2 Anemia , 65, 71 Bladder exstrophy , 118 Anencephaly , 108 Body surface area (BSA) , 29 Antenatal steroids , 60 Body weight , 29 Aortic stenosis , 63 Bolus , 35 Apgar score , 40 Botulinum , 66 Aplasia cutis , 134 Brachial plexus injury , 44 Apnea , 40 Breast abscess/mastitis , 67 Apt , 38 Breast-fed jaundice , 47 Arthrogryposis , 83 Breast feeding , 33, 36 Aspiration , 35 Breast milk , 36 Association , 84 Bronchopulmonary dysplasia , 58 Atrial septal defects , 65 Brown fat , 29 Attentional disorders , 15 Bruxism , 21 Attention-defi cit disorder (ADD) , 14 BSA. See Body surface area (BSA) Attention-defi cit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) , 14 Automatisms , 16 C Caloric requirements , 39 Caput succedaneum , 135 B Cephalohematoma , 78, 135 Babble , 2 Cerebral bruit , 99 Babinski refl ex , 25 CHARGE , 85 C.M. Houser, Pediatric Development