SPC Fisheries Newsletter #138 (May-August 2012)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Vanuatu's Draft National Ocean Policy Consultations

Report on Vanuatu’s Draft National Ocean Policy Consultations Our Ocean Our Culture Our People 2 | Report on Vanuatu’s Draft National Ocean Policy Consultations 2016 Report on Vanuatu’s Consultations regarding the Draft National Ocean Policy As at 27 April 2016 By the Ocean Sub Committee of the National Committee on Maritime Boundary Delimitation, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Acknowledgements This document has been prepared by the Ocean Sub Committee of the National Committee for Maritime Boundary Delimitation with the assistance of the Ministry of Tourism. We thank the MACBIO project (implemented by GIZ with technical support from IUCN and SPREP; funded by BMUB) for their support. We thank the government staff who contributed to the National Consultations, Live and Learn Vanuatu for their administrative support. We are especially grateful to the communities, government staff and other stakeholders throughout the country who contributed their ideas and opinions to help ensure the future of Vanuatu’s ocean. MACBIO Marine and Coastal Biodiversity Management in Pacific Island Countries Report on Vanuatu’s Draft National Ocean Policy Consultations 2016 | 3 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY __________________________________________________________________________6 1 Introduction _______________________________________________________________________________ 7 2 Methods ___________________________________________________________________________________8 3 Using the input from consultations ________________________________________________________ -

Subject/ Area: Vanuatu at the Speed We Cruise, It Will Take Us More Than

Subject/ Area: Vanuatu At the speed we cruise, it will take us more than one season to cover Vanuatu! During this past 4 months, we explored the Southern part of Vanuatu: Tanna, Aniwa, Erromango and Efate. The ultimate cruising guide for Vanuatu is the Rocket Guide (nicknamed Tusker guide, from the first sponsor - www.cruising-vanuatu.com). With charts, aerial photos and sailing directions to most anchorages, you will have no problem making landings. We also used Bob Tiews & Thalia Hearns Vanuatu cruising guide and Miz Mae’s Vanuatu guide. Those 3 reference guides and previous letters in the SSCA bulletins will help you planning a great time in Vanuatu! CM 93 electronic charts are slightly off so do not rely blindly on them! At time of writing, 100 vatu (vt) was about $1 US. Tanna: Having an official port of entry, this island was our first landfall, as cruising NW to see the Northern islands will be easier than the other way around! Port Resolution: We arrived in Port Resolution early on Lucky Thursday…lucky because that is the day of the week that the Customs and Immigration officials come the 2 1/2 hour, 4-wheel drive across from Lenakel. We checked in at no extra cost, and avoided the expense of hiring a transport (2000 vatu RT). We met Werry, the caretaker of the Port Resolution “yacht club”, donated a weary Belgian flag for his collection, and found out about the volcano visit, tours, and activities. Stanley, the son of the Chief, is responsible for relations with the yachts, and he is the tour guide or coordinator of the tours that yachties decide to do. -

Cook Islands

PACIFIC PORTS DIRECTORY 2014 Port Information List Country Ports Page AMERICAN SAMOA 5 Pago Pago 8 COOK ISLANDS 11 Arutanga (Aitutaki) 14 Avatiu (Rarotonga) 17 FIJI 21 Malau (Labasa) 24 Lautoka 26 Levuka 28 Savusavu 29 Suva 32 FRENCH POLYNESIA 37 Bora-Bora 40 Papeete 41 FEDERATED STATES OF MICRONESIA 45 Chuuk 48 Kosrae 50 Pohnpei 51 Yap 53 GUAM 57 Apra 60 KIRIBATI 65 Betio (Tarawa) 68 MARSHALL ISLANDS 71 Kwajalein 74 Majuro 75 NAURU 79 Nauru 81 NEW CALEDONIA 85 Babouillat 88 Baie Ugue 89 Kouaoua 91 1 PACIFIC PORTS DIRECTORY 2014 Country Ports Page Nepoui 92 Noumea 94 Poro 96 Thio 97 PALAU 101 Malakal 104 PAPUA NEW GUINEA 107 Aitape 118 Alotau 119 Buka 120 Daru 121 Kavieng 123 Kieta 124 Kimbe 126 Lae 127 Lorengau 129 Madang 130 Oro Bay 132 Port Moresby 133 Rabaul 134 Vanimo 136 Wewak 137 SAMOA 141 Apia 143 SOLOMON ISLANDS 147 Allardyce Harbour 150 Aola Bay 151 Gizo 152 Honiara 154 Malloco Bay 155 Noro 157 Tonga 161 ss Nuku’alofa 164 2 PACIFIC PORTS DIRECTORY 2014 Country Ports Page Pangai 165 Port Neiafu (Vava;u) 167 TUVALU 171 Funafuti 173 VANUATU 177 Port Vila 180 Port Luganville (Santo) 182 WALLIS & FUTUNA 185 Leava 188 Mata’Utu 189 Information on Quarantine can be viewed on page 192 Fiji Ports CorPoration Limited invites you to Fiji We provide: • Competitive Tariff Structure • Efficient cargo handling • Safe port and anchorage • Reliable, and friendly ports service • Cost effective storage facilities • Excellent wharf infrastructure FIJI PORTS CORPORATION LIMITED Muaiwalu House, Lot 1 Tofua street, Walu Bay, Suva P O Box 780, Suva, Fiji Island • Telephone: (679) 331 2700 Facsimile: (679) 330 0064 • Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.fijiports.com.fj 3 PACIFIC PORTS DIRECTORY 2014 4 PACIFIC PORTS DIRECTORY 2014 AMERICAN SAMOA Subject Information 1 Location 14 deg 18 min South 170 deg 42 min West 2 Capital city Pago Pago (Tutuila Island) 3 Currency US dollar (US$). -

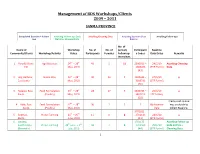

Management of BDS Workshops/Clients 2009 – 2011

Management of BDS Workshops/Clients 2009 – 2011 SANMA PROVINCE Completed Baseline + Follow Awaiting Follow ups Data Awaiting Cleaning Data Awaiting Baseline Data Awaiting Follow ups ups Entries+ Cleaning Data Entries. No. of Name of Workshop No. of No. of (actual) Participant Baseline Community/Clients Workshop/Activity Dates Participants Females Follow up s Codes Data Dates Remarks Interviews. 1. Fanafo/Stone Agri Business 24th – 28th 43 5 11 230001S – 24/5/10 Awaiting Cleaning Hill May, 2010 230043S (ETF Forms) Data. (43) 2. Hog Harbour, Home Stay 24th – 28th 30 22 7 330044S – 27/5/10 ↓ East Santo May, 2010 330073S (ETF Forms) (30) 3. Natawa, East Feed Formulation 25th – 28th 28 17 7 340074S – 25/5/10 ↓ Santo (Poultry) May, 2010 340101S ETF Forms) (28) Fremy said no one 4. Kole, East Feed Formulation 27th – 28th 30 ? ? ? No Baseline was available to Santo (Poultry) May, 2010 data collect Baseline. 370102S – 5. Bodmas, Prawn Farming 21st – 25th 11 0 2 370112S 24/6/10 ↓ Santo June, 2010 (11) (ETF Forms) 6. Ipayato, 370113S – Awaiting Follow up South Santo Prawn Farming 28th June – 2nd 44 7 6 370156S 29/6/10 Data entries + (Kerevalis) July, 2010 (44) (ETF Forms) Cleaning Data. 1 17th – 18th 7. Malo Plantation June, 2010 12 ? ? ? No Baseline MEO not aware of Management data this training. Awaiting Follow up 8. Tassiriki, Agri Business 27th Sept. – 1st 33 18 3 580157S – 30/9/10 Data entries + South Santo Oct. 2010 580189S Cleaning Data. (33) 9. Port Orly, East Food Preparation 13th – 19th 23 20 5 610190S – 15/9/10 Awaiting Cleaning Santo Sept. -

Tanna Island - Wikipedia

Tanna Island - Wikipedia Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Tanna Island From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates : 19°30′S 169°20′E Tanna (also spelled Tana) is an island in Tafea Main page Tanna Contents Province of Vanuatu. Current events Random article Contents [hide] About Wikipedia 1 Geography Contact us 2 History Donate 3 Culture and economy 3.1 Population Contribute 3.2 John Frum movement Help 3.3 Language Learn to edit 3.4 Economy Community portal 4 Cultural references Recent changes Upload file 5 Transportation 6 References Tools 7 Filmography Tanna and the nearby island of Aniwa What links here 8 External links Related changes Special pages Permanent link Geography [ edit ] Page information It is 40 kilometres (25 miles) long and 19 Cite this page Wikidata item kilometres (12 miles) wide, with a total area of 550 square kilometres (212 square miles). Its Print/export highest point is the 1,084-metre (3,556-foot) Download as PDF summit of Mount Tukosmera in the south of the Geography Printable version island. Location South Pacific Ocean Coordinates 19°30′S 169°20′E In other projects Siwi Lake was located in the east, northeast of Archipelago Vanuatu Wikimedia Commons the peak, close to the coast until mid-April 2000 2 Wikivoyage when following unusually heavy rain, the lake Area 550 km (210 sq mi) burst down the valley into Sulphur Bay, Length 40 km (25 mi) Languages destroying the village with no loss of life. Mount Width 19 km (11.8 mi) Bislama Yasur is an accessible active volcano which is Highest elevation 1,084 m (3,556 ft) Български located on the southeast coast. -

Beachfront Resort

Vanuatu YOUR DIVING HOLIDAY SPECIALIST Dive Adventures Vanuatu Vanuatu is an archipelago of 83 coral and volcanic islands sprinkled across 450,000 square kilometres of the South Pacific Ocean. This untouched paradise is only a few flying hours from the east coast of Australia. Its’ closest neighbours are: Fiji to the east, New Caledonia to the south and the Solomon Islands to the north. Formally known as the New Hebrides, the group of islands was declared a condominium in 1906 with the British Queen of French President, joint heads of state. ©Kirklandphotos.com As the economy grew the Melanesian people became more active in their own politics and began dreaming of independence. In 1980 the dream became reality with the first President of the Republic being elected and Vanuatu, meaning “our land”, was born. Happy Ni Vanuatu children General Information: Climate: Summer: November to March average temperatures of 28°C . Winter: April to October average temperatures of 23°C . Water Temperature: Varies from 21°C-27°C. The People: Mostly Melanesian, known as Ni Vanuatu Language:The official language of Vanuatu is Bislama (Pidgin English) English and French and are also widely spoken. Currency: The Vatu is the local currency. Australian dollars and most of the major credit cards, are accepted at mainland hotels, resorts and restaurants. Outer islands will vary. Electricity: 220-240 volts 50Hz. Dress: Light casual clothing, a sweater for the cooler evenings. Clothing should not be too brief, especially when worn outside the hotel perimeters. Medical: Malaria precautions may be necessary when visiting some of Vanuatu offers the visitor a diversity of experiences. -

Fragum Vanuatuense Spec. Nov., a Small New Fragum from the Central Indo-West Pacific (Bivalvia, Cardiidae)

B2015-16:Basteria-2015 11/20/2015 3:15 PM Page 114 Fragum vanuatuense spec. nov., a small new Fragum from the Central Indo-West Pacific (Bivalvia, Cardiidae) Jan Johan ter Poorten Field Museum of Natural History , Department of Zoology (Invertebrates) , 1400 S. Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605-2496, U.S.A. Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, NL-2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands; [email protected] (Kirkendale, 2009; Herrera et al ., 2015). Lacking more Fragum vanuatuense spec. nov. (Cardiidae) is described elaborate DNA data and a formal taxonomic revision, from various localities in the central Indo-West Pacific. the classification of Fragum species remains problem - It represents the smallest Fragum and is compared atic . At present, the World Register of Marine Species with F. grasi Ter Poorten, 2009 and F. sueziense (Issel, (WoRMS) recognizes eight accepted species (Ter 114 1869), both occurring partly sympatric with F. vanuat - Poorten & Bouchet, 2015), six of which were dealt uense spec. nov. Figures of the juvenile growth stages with by Ter Poorten (2009), treating the Cardiidae of of six Fragum species are given for comparison . the 2004 Panglao Marine Biodiversity Project and the Panglao 2005 Deep-Sea Cruise. The present study is Key words: Bivalvia, Cardiidae, Indo-Pacific, Recent, taxonomy, largely based on Fragum material of another large new species, distribution scale expedition: the 2006 Santo Marine Biodiversity Survey to Espiritu Santo, Vanuatu (SANTO 2006) that yielded a total of six Fragum species. Collection re - Introduction search makes clear that small Fragum species have been largely neglected and often have been lumped The genus Fragum Röding, 1798 , is widely distributed together with larger, more well known species or have in the Indo-Pacific, invariably occupying shallow been left unidentified. -

Vanuatu's 2020 Humanitarian Emergencies and Women's

Vanuatu’s 2020 Humanitarian Emergencies and Women’s Experiences: Responses by the Vanuatu Women’s Centre Tropical Cyclone Harold caused devastation throughout Penama, Sanma and Malampa province in April 2020 August 2020 Supported by the Pacific Partnership to End Violence Against Women and Girls (Pacific Partnership) 2 Contents Introduction: the humanitarian context ................................................................................................. 4 VWC’s emergency response activities: mobile counselling and relief distribution ................................ 5 Community experiences and responses ................................................................................................. 7 Women’s and girls’ experiences and gender equality issues ............................................................... 11 Conclusions, lessons learned and recommendations to other agencies .............................................. 13 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the Vanuatu Women’s Centre (VWC) and is based on discussions at a mini-retreat with VWC and Branch staff in July 2020, and mobile counselling reports from VWC and Branch staff to areas affected by the 2020 emergencies. The humanitarian response activities described in this report were funded by the following donors: VWC’s core national program is funded by the Australian Aid Program, including some of the humanitarian response activities described in this report. VWC is supported by UN Women funding from the Pacific Partnership to End Violence Against Women and Girls (Pacific Partnership) Programme, funded primarily by the European Union with targeted support from the Governments of Australia and New Zealand and cost-sharing with UN Women. Oxfam Vanuatu has recently become a funding partner and is providing support for activities in Malampa province, including VWC’s response to Tropical Cyclone Harold. Disclaimer: This publication has been produced with the financial support of the European Union and the Governments of Australia and New Zealand, and UN Women. -

Benthic Algal and Seagrass Communities from Santo Island in Relation to Habitat Diversity

in BOUCHET P., LE GUYADER H. & PASCAL O. (Eds), The Natural History of Santo. MNHN, Paris; IRD, Marseille; PNI, Paris. 572 p. (Patrimoines naturels; 70). Algal and Seagrass Communities from Santo Island in Relation to Habitat Diversity Claude E. Payri The coral reef communities of Vanuatu five species from Santo, i.e. Cymodocea rotundata, have been little studied and nothing Halodule uninervis, H. pinifolia, Halophila ovalis and has been previously published on Thalassia hemprechii. the benthic algal flora from Espiritu Santo Island. Some marine algae The present algal flora and seagrass investigation of from Vanuatu have been found in Santo was conducted during August 2006 as part of the British Museum collections (BM) the "Santo 2006 expedition". This work is a com- and are mainly Sargassum species and panion study to that of the Solomons and Fiji and is Turbinaria ornata. In their report on intended to provide data for ongoing biogeographic Vanuatu’s marine resources, Done and work within the West and Central Pacific. Benthic Navin (1990) mentioned Halimeda opuntia as occurring in most of the Extensive surveys have been carried out in most sites investigated and noted the high encrustation of the habitats recognized in the southern part of of coralline algae in exposed sites. More work has Santo Island and in the Luganville area, including been done on seagrass communities; earlier authors islands, shorelines, reef flats, channels and deep reported a total of nine species from Vanuatu including outer reef slopes. SAMPLING SITES AND METHODS The 42 sites investigated are shown in figure 409 species list for the southern part of Santo. -

0=AFRICAN Geosector

3= AUSTRONESIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 301 35= MANUSIC covers the "Manus+ New-Britain" reference area, part of the Papua New Guinea 5 "Oceanic" affinity within the "Austronesian" intercontinental phylozone affinity; comprising 9 sets of languages (= 82 outer languages) spoken by communities in Australasia, on Manus, New Ireland, New Britain and other adjacent islands of Papua New Guinea: 35-A WUVULU+ SEIMAT 35-B SISI+ BALUAN 35-C TUNGAG+ KUANUA 35-D NAKANAI+ VITU 35-E LAMOGAI+ AMARA* 35-F SOLONG+ AVAU* 35-G KAPORE+ MANGSENG* 35-H MAENG+ UVOL* 35-I TUMOIP 35-A WUVULU+ SEIMAT set 35-AA WUVULU+ AUA chain 35-AAA WUVULU+ AUA net 35-AAA-a Wuvulu+ Aua aua+ viwulu, viwulu+ aua Admiralty islands: Wuvulu+ Aua islands Papua New Guinea (Manus) 3 35-AAA-aa wuvulu viwulu, wuu Wuvulu, Maty islan Papua New Guinea (Manus) 2 35-AAA-ab aua Aua, Durour islan Papua New Guinea (Manus) 2 35-AB SEIMAT+ KANIET chain 35-ABA SEIMAT net NINIGO 35-ABA-a Seimat ninigo Admiralty islands: Ninigo islands Papua New Guinea (Manus) 2 35-ABA-aa sumasuma Sumasuma island Papua New Guinea (Manus) 35-ABA-ab mai Mai island Papua New Guinea (Manus) 35-ABA-ac ahu Ahu islan Papua New Guinea (Manus) 35-ABA-ad liot Liot islan Papua New Guinea (Manus) 35-ABB KANIET* net ¶extinct since 1950 X 35-ABB-a Kaniet-'Thilenius' Admiralty islands: Kaniet, Anchorite, Sae+ Suf islands Papua New Guinea (Manus) 0 35-ABB-aa kaniet-'thilenius' Thilenius's kaniet Papua New Guinea (Manus) 0 35-ABB-b Kaniet-'Smythe' Admiralty islands: Kaniet, Anchorite, Sae+ Suf islands Papua New Guinea (Manus) 0 35-ABB-ba kaniet-'smythe' Smythe's kaniet Papua New Guinea (Manus) 0 35-B SISI+ BALUAN set MANUS 35-BA SISI+ LEIPON chain manus-NW. -

Poirieria 09-10

VOL. 9. PART 1. JUNE 1977* CONCHOLOGY SECTION AUCKLAND INSTITUTE & MUSEUM . POIRIERIA Vol 9 Part 1 June 1977 JALCIS ( PICTOBALCIS ) APTICULATA (Sowerby) While the shells of our small, very slender species of the genus Bale is are invariably white - sometimes porcellanous and sometimes glossy - we seem to have gained fairly recently a species which is delightfully different. This is Pictobalcis articulata ., first recorded from New South Wales, and now not infrequently collected in beach drifts from Cape Maria .to at least as far South as Whangaruru. The first examples recorded in New Zealand were collected in 1971. The subgenus was apparently erected to contain those species which sport a colour pattern, and articulata has a very pleasing one - a central band of chestnut from which narrow chevrons extend from both sides , reaching almost to the sutures, Size of Cape Maria specimen. ' while from each varix runs a vertical stripe on the base of the shell. Ground colour is porcellanous white. The largest examples I have seen came from Cape Maria van Diemen and measured just over '30mm x which is considerably larger than the type specimen from Australia. The molluscs belonging to this genus are parasitic - mostly on echinoderms, but v;e dOj in fact, know very little about the hosts of our own New Zealand. species , most of which are no more than 5 or 6 ram in length. * * * * * A NOTE ON DREDGING OFF TOLAGA BAY R, M. Lee On a recent dredging trip off Tolaga Bay, where I live, I hopefully tried a- new location about four miles offshore in 26 - 28 fathoms on mud and sand bottom. -

National Integrated Coastal Management Framework and Implementation Strategy for Vanuatu

National Integrated Coastal Management Framework and Implementation Strategy for Vanuatu A National Approach to Cooperative Integrated Coastal Management 4 December 2010 1 Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations Executive Summary NATIONAL INTEGRATED COASTAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK 1. INTRODUCTION 7 1.1 Coastal Resources of Vanuatu 7 1.2 Coastal Environment Issues 9 1.3 Development of a NICMF 2. COASTAL ZONE PRESSURES 13 2.1 Coastal Development 14 2.2 Coastal Fisheries 14 2.3 Tourism 16 2.4 Land Based Impacts 17 2.5 Marine and Maritime Activities 18 2.6 Climate Change and Sea Level Rise 18 13. NATIONAL INTEGRATED COASTAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK 21 3.1 Scope 21 3.2 Vision Statement 21 3.3 Mission Statement 21 3.4 Goal 22 3.5 Objectives 22 3.6 Institutions and Organizations Involved in Coastal Management 22 3.7 Existing Legislation and Policies 23 3.8 Implementation of the NICMF 25 NATIONAL INTEGRATED COASTAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK 26 IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY 1. National Issues 26 2. National Roles and Responsibilities 26 3. Tools and Strategies Available for ICM 27 4. National Implementation Strategy for ICM 31 5. Developing Area ICM Plans 32 6. Integrating the NICMF 35 7. Capacity Building 35 8. Monitoring and Evaluation 36 9. Next Steps 38 Resources Consulted 39 2 National Coastal Management Framework for Vanuatu Acronyms and abbreviations ACIAR Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research CCM Cooperative Coastal Management CMT customary marine tenure system COLP Code of Logging Practice COT crown of thorn starfish CRISP Coral