Arxiv:1807.10772V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 27 Jul 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter Constellations

Winter Constellations *Orion *Canis Major *Monoceros *Canis Minor *Gemini *Auriga *Taurus *Eradinus *Lepus *Monoceros *Cancer *Lynx *Ursa Major *Ursa Minor *Draco *Camelopardalis *Cassiopeia *Cepheus *Andromeda *Perseus *Lacerta *Pegasus *Triangulum *Aries *Pisces *Cetus *Leo (rising) *Hydra (rising) *Canes Venatici (rising) Orion--Myth: Orion, the great hunter. In one myth, Orion boasted he would kill all the wild animals on the earth. But, the earth goddess Gaia, who was the protector of all animals, produced a gigantic scorpion, whose body was so heavily encased that Orion was unable to pierce through the armour, and was himself stung to death. His companion Artemis was greatly saddened and arranged for Orion to be immortalised among the stars. Scorpius, the scorpion, was placed on the opposite side of the sky so that Orion would never be hurt by it again. To this day, Orion is never seen in the sky at the same time as Scorpius. DSO’s ● ***M42 “Orion Nebula” (Neb) with Trapezium A stellar nursery where new stars are being born, perhaps a thousand stars. These are immense clouds of interstellar gas and dust collapse inward to form stars, mainly of ionized hydrogen which gives off the red glow so dominant, and also ionized greenish oxygen gas. The youngest stars may be less than 300,000 years old, even as young as 10,000 years old (compared to the Sun, 4.6 billion years old). 1300 ly. 1 ● *M43--(Neb) “De Marin’s Nebula” The star-forming “comma-shaped” region connected to the Orion Nebula. ● *M78--(Neb) Hard to see. A star-forming region connected to the Orion Nebula. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Evolution of Star Clusters in Time-Variable Tidal Fields

Evolution of Star Clusters in Time-Variable Tidal Fields A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Ernest N. Mamikonyan in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 12, 2013 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 TypesofStarClusters............................ 2 1.1.1 GlobularClusters .......................... 3 1.1.2 OpenClusters............................ 4 1.2 Mass Function: From Young to Globular . 5 2 Arbitrary Tidal Acceleration 8 2.1 ApproximatingTidalEffects. 9 2.1.1 Tidal Acceleration Tensor . 10 2.2 Stellar Dynamics with KIRA ........................ 11 2.2.1 CircularOrbitinPoint-MassPotential . 14 2.3 GalaxyMergerSimulations . 16 2.3.1 TidalHistories............................ 19 2.4 N-BodySimulations ............................ 24 2.4.1 N-BodyUnits ............................ 26 2.4.2 Scaling ................................ 26 3 Mass Loss Model 30 i 3.1 Accelerated Two-Body Relaxation . 30 3.2 FluctuationsintheJacobiRadius. 34 3.3 Results .................................... 36 3.4 Discussion.................................. 37 3.4.1 Limitations ............................. 40 4 Globular Cluster Mass Functions 44 4.1 MassFunctionEvolution . 47 4.2 Results .................................... 48 4.2.1 SinkParticles ............................ 48 4.2.2 DiskParticles ............................ 50 4.2.3 HaloParticles ............................ 55 5 Conclusions and Future Work 57 Appendix A Implementation of Tidal Fields in KIRA 63 Appendix B Computing Tidal Acceleration from GADGET Output 66 ii List of Figures 1.1 Infrared image of the globular cluster Omega Centauri. It is the most massive cluster in the Galaxy and thought to be a remnant of a dwarf galaxy absorbed by the Milky Way. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/ NOAO/AURA/NSF)............................. 3 1.2 The Pleiades open cluster in the infrared. It is one of the most well- known and spectacular objects in the Galaxy. -

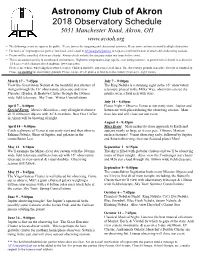

2018 Observatory Schedule

Astronomy Club of Akron 2018 Observatory Schedule 5031 Manchester Road, Akron, OH www.acaoh.org – The following events are open to the public. Please join us for stargazing and educational activities. Please arrive on time to avoid headlight distraction. – For notice of “impromptu star parties” not listed, send e-mail to [email protected] to request e-mail notification of unscheduled observing sessions. – Events will be cancelled if skies are cloudy. Always check website for star party status two hours before event. – This is an outdoor activity in an unheated environment. Nighttime temperatures drop rapidly, even during summer. A general rule of thumb is to dress for 15 degrees colder than predicted nighttime low temperature. – Please respect those who bring their own telescopes. Children should be supervised at all times. The observatory grounds is no place for toys or tomfoolery. – Please, no smoking on observatory grounds. Please, no use of cell phones or tablets in observatory (to preserve night vision). March 17 – 7:45pm July 7 – 9:00pm View the Great Orion Nebula & the beautiful star clusters of The Ring Nebula is a stunning sight in the 16” observatory Auriga through the 16” observatory telescope and view telescope; placed in the Milky Way, observers can see the Pleiades, Hyades, & Beehive Cluster through the 100mm nebula set in a field rich with stars. wide field telescope. Sky Tour: Winter Constellations July 14 – 8:45pm April 7 – 8:00pm Planet Night – Observe Venus at star party start. Jupiter and Special Event: Messier Marathon – stay all night to observe Saturn are well-placed during the observing session. -

Celebrating the Wonder of the Night Sky

Celebrating the Wonder of the Night Sky The heavens proclaim the glory of God. The skies display his craftsmanship. Psalm 19:1 NLT Celebrating the Wonder of the Night Sky Light Year Calculation: Simple! [Speed] 300 000 km/s [Time] x 60 s x 60 m x 24 h x 365.25 d [Distance] ≈ 10 000 000 000 000 km ≈ 63 000 AU Celebrating the Wonder of the Night Sky Milkyway Galaxy Hyades Star Cluster = 151 ly Barnard 68 Nebula = 400 ly Pleiades Star Cluster = 444 ly Coalsack Nebula = 600 ly Betelgeuse Star = 643 ly Helix Nebula = 700 ly Helix Nebula = 700 ly Witch Head Nebula = 900 ly Spirograph Nebula = 1 100 ly Orion Nebula = 1 344 ly Dumbbell Nebula = 1 360 ly Dumbbell Nebula = 1 360 ly Flame Nebula = 1 400 ly Flame Nebula = 1 400 ly Veil Nebula = 1 470 ly Horsehead Nebula = 1 500 ly Horsehead Nebula = 1 500 ly Sh2-106 Nebula = 2 000 ly Twin Jet Nebula = 2 100 ly Ring Nebula = 2 300 ly Ring Nebula = 2 300 ly NGC 2264 Nebula = 2 700 ly Cone Nebula = 2 700 ly Eskimo Nebula = 2 870 ly Sh2-71 Nebula = 3 200 ly Cat’s Eye Nebula = 3 300 ly Cat’s Eye Nebula = 3 300 ly IRAS 23166+1655 Nebula = 3 400 ly IRAS 23166+1655 Nebula = 3 400 ly Butterfly Nebula = 3 800 ly Lagoon Nebula = 4 100 ly Rotten Egg Nebula = 4 200 ly Trifid Nebula = 5 200 ly Monkey Head Nebula = 5 200 ly Lobster Nebula = 5 500 ly Pismis 24 Star Cluster = 5 500 ly Omega Nebula = 6 000 ly Crab Nebula = 6 500 ly RS Puppis Variable Star = 6 500 ly Eagle Nebula = 7 000 ly Eagle Nebula ‘Pillars of Creation’ = 7 000 ly SN1006 Supernova = 7 200 ly Red Spider Nebula = 8 000 ly Engraved Hourglass Nebula -

The Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram Help Sheet

School of Physics and Astronomy Edgbaston Birmingham B15 2TT The Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram Help Sheet Setting up the Telescope What is the wavelength range of an optical telescope? Approx. 400 - 700 nm Locating the Star Cluster Observing the sky from the Northern hemisphere, which star remains fixed in the sky whilst the other stars rotate around it? In which direction do they rotate? North Star/Pole Star/Polaris Stars rotate anticlockwise around Polaris Observing the Star Cluster - Stellar Observation What is the difference between the apparent magnitude and the absolute magnitude of a star? The apparent magnitude is how bright the star appears from Earth. The absolute magnitude is how bright the star would appear if it was 10pc away from Earth. Part 1 - Distance to the Star Cluster What is the distance to the star cluster in lightyears? 136 pc = 444 lightyears Conversion: 1 pc = 3.26 lightyears Why might the distance to the cluster you have calculated differ from the literature value? Uncertainty in fit of ZAMS (due to outlying stars, for example), hence uncertainty in distance modulus and hence distance. Part 2 - Age of the Star Cluster Why might there be an uncertainty in the age of the cluster determined by this method? Uncertainty in fit of isochrone; with 2 or 3 parameters to fit it can be difficult to reproduce the correct shape. Also problem with outlying stars, as explained in the manual. How does the age you have calculated compare to the age of the universe? Age of universe ~ 13.8 GYr Part 3 - Comparison of Star Clusters Consider the shape of the CMD for the Hyades. -

Star Map 01 January 2021

Night sky map January 2021 STAR BRIGHTNESS Zero or brighter st 1 magnitude nd 2 Andromeda Galaxy 3rd 4th Hyades M1Hyades - Crab Nebula M45 - Pleiades Mars P First Quarter Moon on the 21st Orion’s belt M42 - Orion Nebula The “Saucepan” M2 Fomalhaut Mercury P Jupiter P Saturn P Tarantula Nebula 47 Tucanae False Cross Carina Nebula Southern Cross Chart Key Diamond Cross Bright star Pointers Faint star Ecliptic MOON PHASE Milky Way Last quarter 06th P Planet New Moon 13th LMC or Large Magellanic Cloud First quarter 21st SMC or Small Magellanic Cloud Full Moon 29th THE CHART HIGHLIGHTS IN JANUARY 2021 This star chart shows the stars and constellations visible in the The best time to view the Moon with a small night sky for Sydney, Melbourne, Canberra and Hobart in telescope or pair of binoculars is a few days either January at about 8:30pm (Daylight Savings Time), or 7:30pm side of its first quarter phase on the 21st of January. (Local Standard Time) for Perth and Brisbane. For Darwin and Mars is high in the northern sky after sunset in the similar northerly locations, the chart will still apply, but some constellation of Aries (the Ram). Prominent in the stars will be lost off the southern edge while extra stars will be sky this month, are the constellations of Canis visible to the north. Stars down to a brightness or magnitude Major (the Great Dog) which includes Sirius – the limit of 4.5 are shown on the star chart. To use this star chart, brightest star in the sky and Orion (the Hunter), rotate the chart so that the direction you are facing (north, which includes the recognisable southern south, east or west) is shown at the bottom. -

The Pleiades: the Celestial Herd of Ancient Timekeepers

The Pleiades: the celestial herd of ancient timekeepers. Amelia Sparavigna Dipartimento di Fisica, Politecnico di Torino C.so Duca degli Abruzzi 24, Torino, Italy Abstract In the ancient Egypt seven goddesses, represented by seven cows, composed the celestial herd that provides the nourishment to her worshippers. This herd is observed in the sky as a group of stars, the Pleiades, close to Aldebaran, the main star in the Taurus constellation. For many ancient populations, Pleiades were relevant stars and their rising was marked as a special time of the year. In this paper, we will discuss the presence of these stars in ancient cultures. Moreover, we will report some results of archeoastronomy on the role for timekeeping of these stars, results which show that for hunter-gatherers at Palaeolithic times, they were linked to the seasonal cycles of aurochs. 1. Introduction Archeoastronomy studies astronomical practices and related mythologies of the ancient cultures, to understand how past peoples observed and used the celestial phenomena and what was the role played by the sky in their cultures. This discipline is then a branch of the cultural astronomy, an interdisciplinary field that relates astronomical phenomena to current and ancient cultures. It must then be distinguished from the history of astronomy, because astronomy is a culturally specific concept and ancient peoples may have been related to the sky in different way [1,2]. Archeoastronomy is considered as a quite new interdisciplinary science, rooted in the Stonehenge studies of 1960s by the astronomer Gerald Hawkins, who tested Stonehenge alignments by computer, and concluded that these stones marked key dates in the megalithic calendar [3]. -

Hyades Star Cluster and the New Comets Abstract. We Examined The

Proceedings 49-th International student's conferences "Physics of Space", Kourovka, Ural Federal University (UrFU), 2020. Hyades star cluster and the New comets M. D. Sizova1, E. S. Postnikova1, A. P. Demidov2, N. V. Chupina1, S. V. Vereshchagin1 1Institute of Astronomy, Russian Academy of Sciences, Pyatnitskaya str., 48, 119017 Moscow, Russia 2Central Aerological Observatory, Pervomayskaya str., 3, 141700 Dolgoprudny, Moscow region, Russia [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract. We examined the influence of the Hyades star cluster on the possibility of the appearance of long-period comets in the Solar system. It is known that the Hyades cluster is extended along the spatial orbit on tens of parsecs. To our estimations, 0.85 million years ago, there was a close approach of the cluster to the Sun of 24.8 pc. The approach of one of the cluster stars to the Sun at the minimally known distance of about 6.9 pc was 1.6 million years ago. The main part of the cluster was close to the Sun from 1 to 2 million years ago. Such proximity is not essential for the impact on the dynamics of small bodies in the external part of the Oort cloud, although the view may change after additional study of the cluster structure. Possible orbits perihelion displacements of the small bodies of the outer part of the Oort cloud make some of them in observable comets region. Introduction. The data obtained by Gaia mission allows us to study previously inaccessible details of the structure of stellar systems. -

Caldwell Catalogue - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Caldwell catalogue - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Log in / create account Article Discussion Read Edit View history Caldwell catalogue From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page Contents The Caldwell Catalogue is an astronomical catalog of 109 bright star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies for observation by amateur astronomers. The list was compiled Featured content by Sir Patrick Caldwell-Moore, better known as Patrick Moore, as a complement to the Messier Catalogue. Current events The Messier Catalogue is used frequently by amateur astronomers as a list of interesting deep-sky objects for observations, but Moore noted that the list did not include Random article many of the sky's brightest deep-sky objects, including the Hyades, the Double Cluster (NGC 869 and NGC 884), and NGC 253. Moreover, Moore observed that the Donate to Wikipedia Messier Catalogue, which was compiled based on observations in the Northern Hemisphere, excluded bright deep-sky objects visible in the Southern Hemisphere such [1][2] Interaction as Omega Centauri, Centaurus A, the Jewel Box, and 47 Tucanae. He quickly compiled a list of 109 objects (to match the number of objects in the Messier [3] Help Catalogue) and published it in Sky & Telescope in December 1995. About Wikipedia Since its publication, the catalogue has grown in popularity and usage within the amateur astronomical community. Small compilation errors in the original 1995 version Community portal of the list have since been corrected. Unusually, Moore used one of his surnames to name the list, and the catalogue adopts "C" numbers to rename objects with more Recent changes common designations.[4] Contact Wikipedia As stated above, the list was compiled from objects already identified by professional astronomers and commonly observed by amateur astronomers. -

Survival Rates of Planets in Open Clusters: the Pleiades, Hyades, and Praesepe Clusters M

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. ms c ESO 2019 April 12, 2019 Survival rates of planets in open clusters: The Pleiades, Hyades, and Praesepe clusters M. S. Fujii1 and Y. Hori2,3 1 Department of Astronomy, Graduate School of Science, The University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 1130033, Japan e-mail: [email protected] 2 Astrobiology Center, 2-21-1 Osawa, Mitaka, Tokyo 1818588, Japan 3 National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, 2-21-1 Osawa, Mitaka, Tokyo 1818588, Japan e-mail: [email protected] Received November xx, 2018; accepted xxxx xx, 2018 ABSTRACT Context. In clustered environments, stellar encounters can liberate planets from their host stars via close encounters. Although the detection probability of planets suggests that the planet population in open clusters resembles that in the field, only a few dozen planet-hosting stars have been discovered in open clusters. Aims. We explore the survival rates of planets against stellar encounters in open clusters similar to the Pleiades, Hyades, and Praesepe and embedded clusters. Methods. We performed a series of N-body simulations of high-density and low-density open clusters, open clusters that grow via mergers of subclusters, and embedded clusters. We semi-analytically calculated the survival rate of planets in star clusters up to ∼1 Gyr using relative velocities, masses, and impact parameters of intruding stars. Results. Less than 1.5 % of close-in planets within 1 AU and at most 7 % of planets with 1–10 AU are ejected by stellar encounters in clustered environments after the dynamical evolution of star clusters. -

Mass Effect on the Lithium Abundance Evolution of Open Clusters: Hyades, NGC 752, and M 67 M

A&A 590, A94 (2016) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201527583 & c ESO 2016 Astrophysics Mass effect on the lithium abundance evolution of open clusters: Hyades, NGC 752, and M 67 M. Castro1, T. Duarte1, G. Pace2, and J.-D. do Nascimento Jr.1; 3 1 Departamento de Física Teórica e Experimental, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, 59072-970 Natal, RN, Brazil e-mail: [email protected] 2 Instituto de Astrofísica e Ciência do Espaço, Universidade do Porto, Rua das Estrelas, 4150-762 Porto, Portugal 3 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA Received 16 October 2015 / Accepted 12 March 2016 ABSTRACT Lithium abundances in open clusters provide an effective way of probing mixing processes in the interior of solar-type stars and convection is not the only mixing mechanism at work. To understand which mixing mechanisms are occurring in low-mass stars, we test non-standard models, which were calibrated using the Sun, with observations of three open clusters of different ages, the Hyades, NGC 752, and M 67. We collected all available data, and for the open cluster NGC 752, we redetermine the equivalent widths and the lithium abundances. Two sets of evolutionary models were computed, one grid of only standard models with microscopic diffusion and one grid with rotation-induced mixing, at metallicity [Fe/H] = 0.13, 0.0, and 0.01 dex, respectively, using the Toulouse-Geneva evolution code. We compare observations with models in a color–magnitude diagram for each cluster to infer a cluster age and a stellar mass for each cluster member.