One of the Most Useful Accessories an Amateur Can Possess Is One of the Ubiquitous Optical Filters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stsci Newsletter: 1997 Volume 014 Issue 01

January 1997 • Volume 14, Number 1 SPACE TELESCOPE SCIENCE INSTITUTE Highlights of this issue: • AURA science and functional awards to Leitherer and Hanisch — pages 1 and 23 • Cycle 7 to be extended — page 5 • Cycle 7 approved Newsletter program listing — pages 7-13 Astronomy with HST Climbing the Starburst Distance Ladder C. Leitherer Massive stars are an important and powerful star formation events in sometimes dominant energy source for galaxies. Even the most luminous star- a galaxy. Their high luminosity, both in forming regions in our Galaxy are tiny light and mechanical energy, makes on a cosmic scale. They are not them detectable up to cosmological dominated by the properties of an distances. Stars ~100 times more entire population but by individual massive than the Sun are one million stars. Therefore stochastic effects times more luminous. Except for stars prevail. Extinction represents a severe of transient brightness, like novae and problem when a reliable census of the supernovae, hot, massive stars are Galactic high-mass star-formation the most luminous stellar objects in history is atempted, especially since the universe. massive stars belong to the extreme Massive stars are, however, Population I, with correspondingly extremely rare: The number of stars small vertical scale heights. Moreover, formed per unit mass interval is the proximity of Galactic regions — roughly proportional to the -2.35 although advantageous for detailed power of mass. We expect to find very studies of individual stars — makes it few massive stars compared to, say, difficult to obtain integrated properties, solar-type stars. This is consistent with such as total emission-line fluxes of observations in our solar neighbor- the ionized gas. -

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants As Tracers of Planet Formation

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants as Tracers of Planet Formation Thesis by Marta Levesque Bryan In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California 2018 Defended May 1, 2018 ii © 2018 Marta Levesque Bryan ORCID: [0000-0002-6076-5967] All rights reserved iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to thank Heather Knutson, who I had the great privilege of working with as my thesis advisor. Her encouragement, guidance, and perspective helped me navigate many a challenging problem, and my conversations with her were a consistent source of positivity and learning throughout my time at Caltech. I leave graduate school a better scientist and person for having her as a role model. Heather fostered a wonderfully positive and supportive environment for her students, giving us the space to explore and grow - I could not have asked for a better advisor or research experience. I would also like to thank Konstantin Batygin for enthusiastic and illuminating discussions that always left me more excited to explore the result at hand. Thank you as well to Dimitri Mawet for providing both expertise and contagious optimism for some of my latest direct imaging endeavors. Thank you to the rest of my thesis committee, namely Geoff Blake, Evan Kirby, and Chuck Steidel for their support, helpful conversations, and insightful questions. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to collaborate with Brendan Bowler. His talk at Caltech my second year of graduate school introduced me to an unexpected population of massive wide-separation planetary-mass companions, and lead to a long-running collaboration from which several of my thesis projects were born. -

Ioptron AZ Mount Pro Altazimuth Mount Instruction

® iOptron® AZ Mount ProTM Altazimuth Mount Instruction Manual Product #8900, #8903 and #8920 This product is a precision instrument. Please read the included QSG before assembling the mount. Please read the entire Instruction Manual before operating the mount. If you have any questions please contact us at [email protected] WARNING! NEVER USE A TELESCOPE TO LOOK AT THE SUN WITHOUT A PROPER FILTER! Looking at or near the Sun will cause instant and irreversible damage to your eye. Children should always have adult supervision while observing. 2 Table of Content Table of Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 1. AZ Mount ProTM Altazimuth Mount Overview...................................................................................... 5 2. AZ Mount ProTM Mount Assembly ........................................................................................................ 6 2.1. Parts List .......................................................................................................................................... 6 2.2. Identification of Parts ....................................................................................................................... 7 2.3. Go2Nova® 8407 Hand Controller .................................................................................................... 8 2.3.1. Key Description ....................................................................................................................... -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Skywatch Number 67 (New Series) : Two Eyes

Amateur Astronomy WITH AN ATTITUDE from Chaos Manor South! Rod Mollise’s March-April 2003 Volume 12, Issue 2 “A Newsletter for the Truly Outbound!” Skywatch Number 67 (New Series) : two eyes. Only when it’s time to look <[email protected]> through a telescope do we squint Great, Huge one closed and look at the universe Inside this Issue: through a single peeper. This is SUPERSIZED uncomfortable, and, since our brain is used to getting the input from two eyes, we lose detail. A binoviewer is How I Learned to Stop Issue! the supposed cure. It’s a device that Worrying and Love uses prisms to take the light coming 1 Binoviewers! from your lenses and mirrors, split it, and direct the image into two Lucy Looks Skyward! How I learned to eyepieces. Put one of these on your 2 scope and you can view the Stop Worrying wonders of the heavens through two The EyeOpener! eyes as nature intended. 3 and Love Too bad this idea didn’t seem to MX7C Conversion! work well—at least not for me. Many 4 Binoviewers were the times I’d been offered the Confessions of an Astromart chance to use a binoviewer, given it Junkie! a try, and come away shaking my Denkmeier Optical, Inc. 5 head at the idea anybody could like 100 Pinehurst Road one of these things. Didn’t seem to Berlin, MD 21811 Lunar Software! matter which brand I tried, either, Information:(410)208-6014 Toll-Free 6 including expensive TeleVues and Order Line: (866)340-4578 AP branded units. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Correlations Between the Stellar, Planetary, and Debris Components of Exoplanet Systems Observed by Herschel⋆

A&A 565, A15 (2014) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201323058 & c ESO 2014 Astrophysics Correlations between the stellar, planetary, and debris components of exoplanet systems observed by Herschel J. P. Marshall1,2, A. Moro-Martín3,4, C. Eiroa1, G. Kennedy5,A.Mora6, B. Sibthorpe7, J.-F. Lestrade8, J. Maldonado1,9, J. Sanz-Forcada10,M.C.Wyatt5,B.Matthews11,12,J.Horner2,13,14, B. Montesinos10,G.Bryden15, C. del Burgo16,J.S.Greaves17,R.J.Ivison18,19, G. Meeus1, G. Olofsson20, G. L. Pilbratt21, and G. J. White22,23 (Affiliations can be found after the references) Received 15 November 2013 / Accepted 6 March 2014 ABSTRACT Context. Stars form surrounded by gas- and dust-rich protoplanetary discs. Generally, these discs dissipate over a few (3–10) Myr, leaving a faint tenuous debris disc composed of second-generation dust produced by the attrition of larger bodies formed in the protoplanetary disc. Giant planets detected in radial velocity and transit surveys of main-sequence stars also form within the protoplanetary disc, whilst super-Earths now detectable may form once the gas has dissipated. Our own solar system, with its eight planets and two debris belts, is a prime example of an end state of this process. Aims. The Herschel DEBRIS, DUNES, and GT programmes observed 37 exoplanet host stars within 25 pc at 70, 100, and 160 μm with the sensitiv- ity to detect far-infrared excess emission at flux density levels only an order of magnitude greater than that of the solar system’s Edgeworth-Kuiper belt. Here we present an analysis of that sample, using it to more accurately determine the (possible) level of dust emission from these exoplanet host stars and thereafter determine the links between the various components of these exoplanetary systems through statistical analysis. -

GU Monocerotis: a High-Mass Eclipsing Overcontact Binary in the Young Open Cluster Dolidze 25? J

A&A 590, A45 (2016) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201628224 & c ESO 2016 Astrophysics GU Monocerotis: A high-mass eclipsing overcontact binary in the young open cluster Dolidze 25? J. Lorenzo1, I. Negueruela1, F. Vilardell2, S. Simón-Díaz3; 4, P. Pastor5, and M. Méndez Majuelos6 1 Departamento de Física, Ingeniería de Sistemas y Teoría de la Señal, Escuela Politécnica Superior, Universidad de Alicante, Carretera de San Vicente del Raspeig s/n, 03690 San Vicente del Raspeig, Alicante, Spain e-mail: [email protected] 2 Institut d’Estudis Espacials de Catalunya, Edifici Nexus, c/ Capitá, 2−4, desp. 201, 08034 Barcelona, Spain 3 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, Vía Láctea s/n, 38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 4 Departamento de Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna, Facultad de Física y Matemáticas, Avda. Astrofísico Francisco Sánchez s/n, 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 5 Departamento de Lenguajes y Sistemas Informáticos, Universidad de Alicante, Apdo. 99, 03080 Alicante, Spain 6 Departamento de Ciencias, IES Arroyo Hondo, c/ Maestro Manuel Casal 2, 11520 Rota, Cádiz, Spain Received 30 January 2016 / Accepted 3 March 2016 ABSTRACT Context. The eclipsing binary GU Mon is located in the star-forming cluster Dolidze 25, which has the lowest metallicity measured in a Milky Way young cluster. Aims. GU Mon has been identified as a short-period eclipsing binary with two early B-type components. We set out to derive its orbital and stellar parameters. Methods. We present a comprehensive analysis, including B and V light curves and 11 high-resolution spectra, to verify the orbital period and determine parameters. -

Binocular Double Star Logbook

Astronomical League Binocular Double Star Club Logbook 1 Table of Contents Alpha Cassiopeiae 3 14 Canis Minoris Sh 251 (Oph) Psi 1 Piscium* F Hydrae Psi 1 & 2 Draconis* 37 Ceti Iota Cancri* 10 Σ2273 (Dra) Phi Cassiopeiae 27 Hydrae 40 & 41 Draconis* 93 (Rho) & 94 Piscium Tau 1 Hydrae 67 Ophiuchi 17 Chi Ceti 35 & 36 (Zeta) Leonis 39 Draconis 56 Andromedae 4 42 Leonis Minoris Epsilon 1 & 2 Lyrae* (U) 14 Arietis Σ1474 (Hya) Zeta 1 & 2 Lyrae* 59 Andromedae Alpha Ursae Majoris 11 Beta Lyrae* 15 Trianguli Delta Leonis Delta 1 & 2 Lyrae 33 Arietis 83 Leonis Theta Serpentis* 18 19 Tauri Tau Leonis 15 Aquilae 21 & 22 Tauri 5 93 Leonis OΣΣ178 (Aql) Eta Tauri 65 Ursae Majoris 28 Aquilae Phi Tauri 67 Ursae Majoris 12 6 (Alpha) & 8 Vul 62 Tauri 12 Comae Berenices Beta Cygni* Kappa 1 & 2 Tauri 17 Comae Berenices Epsilon Sagittae 19 Theta 1 & 2 Tauri 5 (Kappa) & 6 Draconis 54 Sagittarii 57 Persei 6 32 Camelopardalis* 16 Cygni 88 Tauri Σ1740 (Vir) 57 Aquilae Sigma 1 & 2 Tauri 79 (Zeta) & 80 Ursae Maj* 13 15 Sagittae Tau Tauri 70 Virginis Theta Sagittae 62 Eridani Iota Bootis* O1 (30 & 31) Cyg* 20 Beta Camelopardalis Σ1850 (Boo) 29 Cygni 11 & 12 Camelopardalis 7 Alpha Librae* Alpha 1 & 2 Capricorni* Delta Orionis* Delta Bootis* Beta 1 & 2 Capricorni* 42 & 45 Orionis Mu 1 & 2 Bootis* 14 75 Draconis Theta 2 Orionis* Omega 1 & 2 Scorpii Rho Capricorni Gamma Leporis* Kappa Herculis Omicron Capricorni 21 35 Camelopardalis ?? Nu Scorpii S 752 (Delphinus) 5 Lyncis 8 Nu 1 & 2 Coronae Borealis 48 Cygni Nu Geminorum Rho Ophiuchi 61 Cygni* 20 Geminorum 16 & 17 Draconis* 15 5 (Gamma) & 6 Equulei Zeta Geminorum 36 & 37 Herculis 79 Cygni h 3945 (CMa) Mu 1 & 2 Scorpii Mu Cygni 22 19 Lyncis* Zeta 1 & 2 Scorpii Epsilon Pegasi* Eta Canis Majoris 9 Σ133 (Her) Pi 1 & 2 Pegasi Δ 47 (CMa) 36 Ophiuchi* 33 Pegasi 64 & 65 Geminorum Nu 1 & 2 Draconis* 16 35 Pegasi Knt 4 (Pup) 53 Ophiuchi Delta Cephei* (U) The 28 stars with asterisks are also required for the regular AL Double Star Club. -

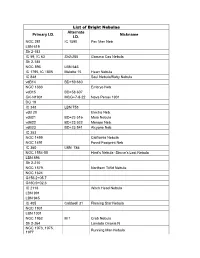

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var. -

Ioptron CEM40 Center-Balanced Equatorial Mount

iOptron®CEM40 Center-Balanced Equatorial Mount Instruction Manual Product CEM40 (#7400A series) and CEM40EC (#7400ECA series, as shown) Please read the included CEM40 Quick Setup Guide (QSG) BEFORE taking the mount out of the case! This product is a precision instrument. Please read the included QSG before assembling the mount. Please read the entire Instruction Manual before operating the mount. You must hold the mount firmly when disengaging the gear switches. Otherwise personal injury and/or equipment damage may occur. Any worm system damage due to improper operation will not be covered by iOptron’s limited warranty. If you have any questions please contact us at [email protected] WARNING! NEVER USE A TELESCOPE TO LOOK AT THE SUN WITHOUT A PROPER FILTER! Looking at or near the Sun will cause instant and irreversible damage to your eye. Children should always have adult supervision while using a telescope. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 3 1. CEM40 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 5 2. CEM40 Overview ................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1. Parts List ......................................................................................................................................... -

Line-Profile Variations of Stochastically Excited

A&A 515, A43 (2010) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/200912777 & c ESO 2010 Astrophysics Line-profile variations of stochastically excited oscillations in four evolved stars S. Hekker1,2,3 and C. Aerts2,4 1 School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK e-mail: [email protected] 2 Instituut voor Sterrenkunde, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200 D, 3001 Leuven, Belgium 3 Royal Observatory of Belgium, Ringlaan 3, 1180 Brussels, Belgium 4 Department of Astrophysics, IMAP, University of Nijmegen, PO Box 9010, 6500 GL Nijmegen, The Netherlands Received 29 June 2009 / Accepted 8 February 2010 ABSTRACT Context. Since solar-like oscillations were first detected in red-giant stars, the presence of non-radial oscillation modes has been de- bated. Spectroscopic line-profile analysis was used in the first attempt to perform mode identification, which revealed that non-radial modes are observable. Despite the fact that the presence of non-radial modes could be confirmed, the degree or azimuthal order could not be uniquely identified. Here we present an improvement to this first spectroscopic line-profile analysis. Aims. We aim to study line-profile variations in stochastically excited solar-like oscillations of four evolved stars to derive the az- imuthal order of the observed mode and the surface rotational frequency. Methods. Spectroscopic line-profile analysis is applied to cross-correlation functions, using the Fourier parameter fit method on the amplitude and phase distributions across the profiles. Results. For four evolved stars, β Hydri (G2IV), Ophiuchi (G9.5III), η Serpentis (K0III) and δ Eridani (K0IV) the line-profile vari- ations reveal the azimuthal order of the oscillations with an accuracy of ±1.