Indigenous Languages in Parliamentary Debate, Legislation and Statutory Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ready Lajamanu Emerged of Families Going Without Food and Some It’S Hurting

FREE November 2016 VOLUME 6. NUMBER 3. PG. ## MARLENE’S FUTURE P.22 IS IN HER HANDS ROYAL COMMISSION WATARRKA POKIES? BREAK OUT YEAR FOR WORRIES WIYA! PRISONER TEAM P. 4 PG. # P. 5 PG. # P. 26 ISSN 1839-5279ISSN NEWS EDITORIAL Want our trust? This time, keep your promises. Land Rights News Central Australia is published by the Central Land Council three We’ll hold you to these election promises: times a year. Aboriginal Hand control to local organisations, develop The Central Land Council workforce training plans and leadership courses with 27 Stuart Hwy organisations them and provide “outposted” public servants to help. Alice Springs Housing $1.1 billion over 10 years for 6500 “additional NT 0870 living spaces”, locally controlled tenancy management and repairs and maintenance, tel: 89516211 capacity development support for local housing www.clc.org.au organisations. email [email protected] Outstations Increase Homelands Extra funding and work with outstation organisations to provide jointly funded Contributions are welcome new houses. As opposition leader, Michael Gunner pleaded with CLC delegates to give Labor a chance to regain their trust. Education Create community led schools with local boards, plan education outcomes for each school region SUBSCRIPTIONS THE MOST extensive return recognises the critically with communities, back community decisions about bilingual education, expand Families as Land Rights News Central of local decision making to important role that control Aboriginal communities since over life circumstances plays First Teachers program, $8 million for nurse Australia subscriptions are self-government, overseen by in improving indigenous home visits of pre-schoolers, support parent $22 per year. -

To Download As

i ii DRIVING DISUNITY The Business Council against Aboriginal community LINDY NOLAN SoE Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide iii Spirit of Eureka publications PO Box 612, Port Adelaide D.C., South Australia 5015 Published by Spirit of Eureka 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Lindy Nolan All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronical, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written per- mission of the publishers of this book. ISBN: 978-0-6481365-0-7 (paperback) 978-0-6481365-1-4 (e-pdf) Printed and bound in Australia by Bullprint, Unit 5, 175 Briens Road Northmead NSW 2152 spiritofeureka.org.au iv About the author Lindy Nolan is a former high school teacher, a union activist and advocate for public education. She served as Custodian and Executive member of the NSW Teachers Federation while remaining a classroom teacher. v Acknowledgements I approached researching and writing this booklet using a scientific method, try- ing to disprove an initial theory that, because profit driven corporations were becoming ever richer and more powerful, and had a terrible track record of tax avoidance, of environmental damage and of running roughshod over Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, they were likely to be up to no good in Abo- riginal communities. I failed in this endeavour. The facts supporting the original theory speak for themselves. Some of the evidence comes from those who stand against the narrative that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples themselves are responsible for the gap between their life expectancy, educational achievement, health and that of others on this continent. -

Northern Territory Election 19 August 2020

Barton Deakin Brief: Northern Territory Election 19 August 2020 Overview The Northern Territory election is scheduled to be held on Saturday 22 August 2020. This election will see the incumbent Labor Party Government led by Michael Gunner seeking to win a second term against the Country Liberal Party Opposition, which lost at the 2016 election. Nearly 40 per cent of Territorians have already cast their vote in pre-polling ahead of the ballot. The ABC’s election analyst Antony Green said that a swing of 3 per cent would deprive the Government of its majority. However, it is not possible to calculate how large the swing against the Government would need to be to prevent a minority government. This Barton Deakin brief provides a snapshot of what to watch in this Territory election on Saturday. Current composition of the Legislative Assembly The Territory has a single Chamber, the Legislative Assembly, which is composed of 25 members. Currently, the Labor Government holds 16 seats (64 per cent), the Country Liberal Party Opposition holds two seats (8 per cent), the Territory Alliance holds three seats (12 per cent), and there are four independents (16 per cent). In late 2018, three members of the Parliamentary Labor Party were dismissed for publicly criticising the Government’s economic management after a report finding that the budget was in “structural deficit”. Former Aboriginal Affairs Minister Ken Vowles, Jeff Collins, and Scott McConnell were dismissed. Mr Vowles later resigned from Parliament and was replaced at a by-election in February 2020 by former Richmond footballer Joel Bowden (Australian Labor Party). -

Electoral Milestones for Indigenous Australians

Electoral milestones for Indigenous Australians Updated: 8 April 2019 Electoral milestones for Indigenous Australians Date Milestone Time Aboriginal society was governed by customary lore before handed down by the creative ancestral beings. memory Captain Cook claimed the eastern half of the 1770 Australian continent for Great Britain. The first fleet arrives in Botany Bay, beginning the British colonisation of Australia. The British 1788 government did not recognise or acknowledge traditional Aboriginal ownership of the land. British sovereignty extended to cover the whole of Australia – everyone born in Australia, including 1829 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, became a British subject by birth. First parliamentary elections in Australia (for New South Wales Legislative Council) were held. The 1843 right to vote was limited to men with a freehold valued at £200 or a householder paying rent of £20 per year. The Australian colonies become self governing – all adult (21 years) male British subjects were entitled to vote in South Australia from 1856, in Victoria from 1850 + 1857, New South Wales from 1858, and Tasmania from 1896 including Indigenous people. Queensland gained self-government in 1859 and Western Australia in 1890, but these colonies denied Indigenous people the vote. Queensland Elections Act excluded all Indigenous 1885 people from voting. Western Australian law denied the vote to 1893 Indigenous people. All adult females in South Australia, including 1895 Indigenous females, won the right to vote. Commonwealth Constitution came into effect, giving the newly-created Commonwealth Parliament the authority to pass federal voting laws. Section 41 prohibited the Commonwealth Parliament from 1901 denying federal voting rights to any individual who, at the time of the Commonwealth Parliament’s first law on federal voting (passed the following year), was entitled to vote in a state election. -

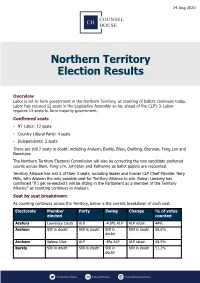

Northern Territory Election Results

24 Aug 2020 Northern Territory Election Results Overview Labor is set to form government in the Northern Territory, as counting of ballots continues today. Labor has secured 12 seats in the Legislative Assembly so far, ahead of the CLP’s 3. Labor requires 13 seats to form majority government. Confirmed seats • NT Labor: 12 seats • Country Liberal Party: 4 seats • Independents: 2 seats There are still 7 seats in doubt, including Araluen, Barkly, Blain, Braitling, Brennan, Fong Lim and Namatjira. The Northern Territory Electoral Commission will also be correcting the two candidate preferred counts across Blain, Fong Lim, Johnston and Katherine as ballot papers are recounted. Territory Alliance has lost 2 of their 3 seats, including leader and former CLP Chief Minister Terry Mills, with Araluen the only possible seat for Territory Alliance to win. Robyn Lambley has confirmed “if I get re-elected I will be sitting in the Parliament as a member of the Territory Alliance” as counting continues in Araluen. Seat by seat breakdown: As counting continues across the Territory, below is the current breakdown of each seat. Electorate Member Party Swing Change % of votes elected counted Arafura Lawrence Costa ALP -4.0% ALP ALP retain 44% Araluen Still in doubt Still in doubt Still in Still in doubt 68.6% doubt Arnhem Selena Uibo ALP -8% ALP ALP retain 48.9% Barkly Still in doubt Still in doubt Still in Still in doubt 51.2% doubt Blain Still in doubt Still in doubt Still in doubt Still in doubt 65% Braitling Still in doubt Still in doubt Still in doubt -

Treaty in the Northern Territory

TREATY IN THE NORTHERN TERRITORY WHAT IS TREATY? HISTORY OF TREATY IN THE NORTHERN TERRITORY WHERE ARE WE UP TO? Find out more antar.org.au/treaty What is Treaty? Treaty can be used to describe a range of agreements between states, nations, governments or people. Treaty can include a single treaty, an overarching treaty with separate side agreements, or multiple treaties with the Northern Territory Government and different Aboriginal groups throughout the Territory. However the Northern Territory may need multiple treaties to be relevant for the lives of individuals and their communities. There may be more than one treaty and more than one Aboriginal group that is a party to a treaty. The Northern Territory’s Government has advised they will openly discuss with Territorians about what treaty means to them and progress a treaty between Aboriginal Territorians and the Government. Discussions with Aboriginal people will determine how they are represented in the treaty making process. “We as a nation must come face to face with our dark and traumatic history. We must confront the impact of A treaty or treaties will set the foundation for colonisation and begin the process of acknowledgment, future agreements between Aboriginal people recognition and healing... Anyone who has listened to and the NT. Treaties can provide the me talk publicly knows that I am concerned with what I call ‘unfinished business’. A Treaty is a good place to opportunity of allowing both parties to negotiate start with addressing this unfinished business” and agree on rights and responsibilities to Professor Mick Dodson, NT Treaty Commissioner establish a long lasting relationship between Photo: Mick Dodson, now NT Treaty Commissioner, pictured in 2001 with the Sea of Hands. -

To Nuclear Waste

= FREE April 2016 VOLUME 6. NUMBER 1. TENANTSPG. ## HIT THE ROOF ABOUT REMOTE HOUSING FAILURE BIG ELECTION YEAR 2016 “NO” TO NUKE DUMP CRICKETERS SHINE P. 5 PG. # P. 6 PG. # P. 30 ISSN 1839-5279ISSN NEWS EDITORIAL Land Rights News Central Australia is published by the Central Land Council three Pressure rises as remote tenants take government to court times a year. AS A SECOND central The Central Land Council Australian community has 27 Stuart Hwy launched legal action against the Northern Territory Alice Springs government and an Alice NT 0870 Springs town camp is following tel: 89516211 suit, the Giles government is under increasing pressure to www.clc.org.au change how it manages remote email [email protected] community and town camp Contributions are welcome houses. Almost a third of Papunya households lodged claims for compensation through SUBSCRIPTIONS the Northern Territory Civil Land Rights News Central Administrative Tribunal in Australia subscriptions are March, over long delays in $20 per year. emergency repairs. A week later, half of the LRNCA is distributed free Larapinta Valley Town Camp Santa Teresa tenant Annie Young says the state of houses in her community has never been worse. to Aboriginal organisations tenants notified the housing and communities in Central department of 160 overdue water all over the front yard, sort told ABC Alice Springs. “Compensation is an Australia repairs, following a survey of like a swamp area,” Katie told “There’s some sort of inertia entitlement under the To subscribe email: by the Central Australian ABC. Some had wires exposed, or blockage in the system that [Residential Tenancies] Act,” [email protected] Aboriginal Legal Aid Service air conditioners not working, when tenants report things he told ABC Alice Springs. -

1 Family Violence in Aboriginal Australian Communities: Causes

1 Family Violence in Aboriginal Australian Communities: Causes and Potential Solutions Political Science Thesis April 25th 2014 Eden Littrell ‘14 I would like to express my gratitude to Carolyn Whyte, Director of Criminal Research and the Statistics Unit in the Northern Territory, and Kevin Schnepel, Lecturer at the University of Sydney, for a couple very informative email conversations. I would also like to thank Professor William Joseph for his advice and my father, Charles Littrell, for proof reading and emotional support. Last, but not least, thank you to my thesis advisor, Professor Lois Wasserspring, for her advice, support and constant feedback throughout this past year. 2 Prologue This thesis is an investigation into why family violence in Aboriginal Australian communities is so severe, and an examination of ways in which this violence might be decreased. I engage with the two competing narratives around violence in Aboriginal communities. The political left typically tells a story about the legacy of violent colonization, and the consequent need to improve Aboriginal legal rights. On the political right the narrative is less well defined, but the argument typically focuses on the importance of personal responsibility, or on the role of traditional culture in creating violence. I argue that competition between these narratives is harmful for actually reducing family violence, and that we should pursue evidence-based policy, such as alcohol restrictions, in addition to trialing and evaluating new policies. In Chapter 1, I briefly outline the higher rates of family violence in Indigenous communities. I also summarize the history of Aboriginal Australians and the contemporary argument around Aboriginal Australians and violence. -

Labor-Ind Seats CLP-Ind Seats % % 53.9

Northern Territory Electoral Pendulum 2020 Labor 14 Independent 1 CLP 8 Independent 2 Total 15 Majority 5 Total 10 Labor-Ind Seats CLP-Ind Seats % % 25 24.3 Nightcliff Nelson (CLP) 22.8 25 20 20 23 19.3 Sanderson 21 17.7 Arnhem 19 17.3 Wanguri 17 16.6 Johnston Spillett (CLP) 15.1 23 SWING TO LABOR PARTY TO SWING 15 16.3 Gwoja SWING TO COUNTRY LIBERAL PARTY COUNTRY TO SWING 13 16.1 Mulka (Ind) 11 16.0 Casuarina 15 15 Goyder (Ind) 14.4 21 Araluen (Ind) 12.7 19 10 10 9 9.8 Karama 7 9.6 Fannie Bay 8 8 5 7.9 Drysdale 4 4 3 3 2 1 1 2 Arafura C Katherine (CLP) L 3.6 P 3 - I n Braitling (CLP) d Brennan (CLP) Fong Lim Namatjira (CLP) M Daly (CLP) a 2.7 Barkly (CLP) jo Port Darwin 2.4 r it y 1 2.1 17 1.3 3 1.3 Blain L 1.2 a b 0.4 15 o 0.1 r - 13 I 0.2 nd M 11 53.9% Labor aj 46.1% CLP o 9 r 7 ity 5 KEY 3.6 Swing required to take seat 3 Majority in seats Result of general election, 22 August 2020 Northern Territory : Two-Party Preferred Votes by Division, 22 August 2020 Division Labor Votes % CLP Votes % %Swing to CLP %Swing Needed Winner Arafura 1,388 53.57 1,203 46.43 3.2 3.6 Lawrence Costa (Labor) Araluen⁽a⁾ 1,630 37.35 2,734 62.65 3.0 12.7 Robyn Lambley (Ind) Arnhem⁽b⁾ 1,977 67.61 947 32.39 -5.2 17.7 Selena Uibo (Labor) Barkly 1,717 49.90 1,724 50.10 16.0 0.1 Steve Edgington (CLP) Blain 2,095 50.16 2,082 49.84 -1.5 0.2 Mark Turner (Labor) Braitling 2,141 48.71 2,254 51.29 4.4 1.3 Joshua Burgoyne (CLP) Brennan 2,138 48.81 2,242 51.19 3.8 1.2 Marie-Clare Boothby (CLP) Casuarina 3,035 65.96 1,566 34.04 -4.6 16.0 Lauren Moss (Labor) Daly 1,890 48.79 -

Northern Gas Pipeline Project ECONOMIC and SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Jemena Northern Gas Pipeline Pty Ltd Northern Gas Pipeline Supplement to the Draft Environmental Impact Statement APPENDIX D ECONOMIC & SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT Public NOVEMBER 2016 This page has been intentionally left blank Supplement to the Draft Environmental Impact Statement for Jemena Northern Gas Pipeline Public— November 2016 © Jemena Northern Gas Pipeline Pty Ltd Northern Gas Pipeline Project ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT PUBLIC Circle Advisory Pty Ltd PO Box 5428, Albany WA 6332 ACN 161 267 250 ABN 36 161 267 250 T: +61 (0) 419 835 704 F: +61 (0) 9891 6102 E: [email protected] www.circleadvisory.com.au DOCUMENT CONTROL RECORD Document Number NGP_PL002 Project Manager James Kernaghan Author(s) Jane Munday, James Kernaghan, Martin Edwards, Fadzai Matambanadzo, Ben Garwood. Approved by Russell Brooks Approval date 8 November 2016 DOCUMENT HISTORY Version Issue Brief Description Reviewer Approver Date A 12/9/16 Report preparation by authors J Kernaghan B 6/10/16 Authors revision after first review J Kernaghan C 7/11/16 Draft sent to client for review J Kernaghan R Brooks (Jemena) 0 8/11/16 Issued M Rullo R Brooks (Jemena (Jemena) Recipients are responsible for eliminating all superseded documents in their possession. Circle Advisory Pty Ltd. ACN 161 267 250 | ABN 36 161 267 250 Address: PO Box 5428, Albany Western Australia 6332 Telephone: +61 (0) 419 835 704 Facsimile: +61 8 9891 6102 Email: [email protected] Web: www.circleadvisory.com.au Circle Advisory Pty Ltd – NGP ESIA Report 1 Preface The authors would like to acknowledge the support of a wide range of people and organisations who contributed as they could to the overall effort in assessing the potential social and economic impacts of the Northern Gas Pipeline. -

Mckeown and Rob Lundie, with Guy Woods *

Conscience Votes in the Federal Parliament since 1996 # Deirdre McKeown and Rob Lundie, with Guy Woods * Introduction In August 2002 we published a Parliamentary Library paper on conscience votes in federal, state and some overseas parliaments. 1 Conscience votes, like instances of crossing the floor, are difficult to find in Hansard, particularly before 1981 when we are forced to rely on hardcopy. In compiling the list of conscience votes we relied on references in House of Representatives Practice . We intend to publish an updated version of our paper when the 41 st parliament ends. Since 2002 we have found some additional procedural conscience votes and have revised some votes included in the original list in House of Representatives Practice . In this paper we consider aspects of conscience votes in the period since 1996. We do not attempt to draw conclusions but rather to track patterns in these votes that have occurred under the Howard government. The aspects considered include voting patterns of party leaders and the party vote, the vote of women, the media and conscience votes and dilemmas facing MPs in these votes. Definitions In our original paper we used the term ‘free vote’ to describe ‘the rare vote in parliament, in which members are not obliged by the parties to follow a party line, but vote according to their own moral, political, religious or social beliefs’.2 # This article has been double blind refereed to academic standards. * Politics and Public Administration Section, Parliamentary Library; Tables prepared by Guy Woods, Statistics and Mapping Section, Parliamentary Library 1 Deirdre McKeown and Rob Lundie, ‘Free votes in Australian and some overseas parliaments’, Current Issues Brief , No. -

NINTH ASSEMBLY 16Th October 2001 to 5 May 2005 INDEX MINUTES

Index to Minutes of Proceedings - 16th October 2001 to 5 May 2005 Ninth Assembly LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY NINTH ASSEMBLY 16th October 2001 to 5 May 2005 INDEX TO MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS AND PAPERS TABLED Consolidated Index to Minutes of Proceedings 16 October 2001 to 5 May 2005 Index Reference Summary by Sitting Day and Minutes Page Minutes Day Date Bound Volume Page 1 - 16 1 16 October 2001 LXIII 17 - 22 2 17 October 2001 LXIII 23 – 29 3 18 October 2001 LXIII 31 – 34 4 23October 2001 LXIII 35 – 39 5 24 October 2001 LXIII 41 - 46 6 25 October 2001 LXIII 47 - 54 7 27 November 2001 LXIII 55 - 61 8 28 November 2001 LXIII 63 - 68 9 29 November 2001 LXIII 69 – 77 10 26 February 2002 LXIV 79 - 88 11 27 February 2002 LXIV 89 – 94 12 28 February 2002 LXIV 95 – 101 13 5 March 2002 LXIV 103 – 108 14 6 March 2002 LXIV 109 - 113 15 7 March 2002 LXIV 115 – 120 16 14 May 2002 LXIV 121 – 125 17 15 May 2002 LXIV 127 – 130 18 16 May 2002 LXIV 131 - 134 19 21 May 2002 LXIV 135 - 139 20 22 May 2002 LXIV 141 - 152 21 23 May 2002 LXIV 153 - 160 22 18 June 2002 LXV 161 - 167 23 19 June 2002 LXV 169 - 178 24 20 June 2002 LXV 179 – 182 25 13 August 2002 LXV 183 – 187 26 14 August 2002 LXV 189 – 193 27 15 August 2002 LXV 195 – 204 28 20 August 2002 LXV 205 – 208 29 21 August 2002 LXV 209 – 212 30 22 August 2002 LXV 213 – 216 31 17 September 2002 LXV 217 - 220 32 19 September 2002 LXV 221 – 228 33 8 October 2002 LXVI 229 – 237 34 9 October 2002 LXVI 239 – 245 35 10 October 2002 LXVI 247 – 249 36 15 October 2002 LXVI 251 – 254 37 16 October