Nutrition and Vitamin Supplements Learning Objectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines on Food Fortification with Micronutrients

GUIDELINES ON FOOD FORTIFICATION FORTIFICATION FOOD ON GUIDELINES Interest in micronutrient malnutrition has increased greatly over the last few MICRONUTRIENTS WITH years. One of the main reasons is the realization that micronutrient malnutrition contributes substantially to the global burden of disease. Furthermore, although micronutrient malnutrition is more frequent and severe in the developing world and among disadvantaged populations, it also represents a public health problem in some industrialized countries. Measures to correct micronutrient deficiencies aim at ensuring consumption of a balanced diet that is adequate in every nutrient. Unfortunately, this is far from being achieved everywhere since it requires universal access to adequate food and appropriate dietary habits. Food fortification has the dual advantage of being able to deliver nutrients to large segments of the population without requiring radical changes in food consumption patterns. Drawing on several recent high quality publications and programme experience on the subject, information on food fortification has been critically analysed and then translated into scientifically sound guidelines for application in the field. The main purpose of these guidelines is to assist countries in the design and implementation of appropriate food fortification programmes. They are intended to be a resource for governments and agencies that are currently implementing or considering food fortification, and a source of information for scientists, technologists and the food industry. The guidelines are written from a nutrition and public health perspective, to provide practical guidance on how food fortification should be implemented, monitored and evaluated. They are primarily intended for nutrition-related public health programme managers, but should also be useful to all those working to control micronutrient malnutrition, including the food industry. -

Vitamins a and E and Carotenoids

Fat-Soluble Vitamins & Micronutrients: Vitamins A and E and Carotenoids Vitamins A (retinol) and E (tocopherol) and the carotenoids are fat-soluble micronutrients that are found in many foods, including some vegetables, fruits, meats, and animal products. Fish-liver oils, liver, egg yolks, butter, and cream are known for their higher content of vitamin A. Nuts and seeds are particularly rich sources of vitamin E (Thomas 2006). At least 700 carotenoids—fat-soluble red and yellow pigments—are found in nature (Britton 2004). Americans consume 40–50 of these carotenoids, primarily in fruits and vegetables (Khachik 1992), and smaller amounts in poultry products, including egg yolks, and in seafoods (Boylston 2007). Six major carotenoids are found in human serum: alpha-carotene, beta-carotene, beta-cryptoxanthin, lutein, trans-lycopene, and zeaxanthin. Major carotene sources are orange-colored fruits and vegetables such as carrots, pumpkins, and mangos. Lutein and zeaxanthin are also found in dark green leafy vegetables, where any orange coloring is overshadowed by chlorophyll. Trans-Lycopene is obtained primarily from tomato and tomato products. For information on the carotenoid content of U.S. foods, see the 1998 carotenoid database created by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Nutrition Coordinating Center at the University of Minnesota (http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/Data/car98/car98.html). Vitamin A, found in foods that come from animal sources, is called preformed vitamin A. Some carotenoids found in colorful fruits and vegetables are called provitamin A; they are metabolized in the body to vitamin A. Among the carotenoids, beta-carotene, a retinol dimer, has the most significant provitamin A activity. -

Vitamin a Fact Sheet

Vitamin A Fact Sheet Why does the body need vitamin A? Vitamin A helps: *To maintain vision in dim light *To keep skin smooth and healthy *To help you grow *To help keep your insides healthy (inner linings of the mouth, ears, nose, lungs, urinary and digestive tract) What foods are good sources of vitamin A? Many orange and dark green vegetables and fruits contain carotenes, natural coloring substances, or pigments. The body can change these pigments into vitamin A. The deeper the green or orange color of the vegetable or the fruit, the more carotenes (and thus vitamin A) it contains. Green Vegetables - broccoli, asparagus, spinach, kale, chard, collards and beet, mustard, turnip or dandelion greens. Orange Fruits and Vegetables - carrots, winter squash, sweet potatoes, tomatoes, pumpkin, apricots, cantaloupes, nectarines, peaches, papaya and mangoes. Watch out! - Color is not always a way to recognize foods rich in vitamin A. Oranges, lemons, grapefruits or tangerines are orange or yellow in color but do not contain much carotene. Also, yams, in contrast to sweet potatoes, have no vitamin A value. Is vitamin A stored in my body? Yes, Vitamin A is stored in the liver, so a rich source of vitamin A does not have to be included in the diet every day. However, vitamin A foods included in the diet every day help to build the body reserve. This may be needed in the case of illness or any time when vitamin A is lacking in the diet. How much vitamin A do I need every day? Recommended intake based on the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI) for Vitamin -

Dietary Supplements Compendium Volume 1

2015 Dietary Supplements Compendium DSC Volume 1 General Notices and Requirements USP–NF General Chapters USP–NF Dietary Supplement Monographs USP–NF Excipient Monographs FCC General Provisions FCC Monographs FCC Identity Standards FCC Appendices Reagents, Indicators, and Solutions Reference Tables DSC217M_DSCVol1_Title_2015-01_V3.indd 1 2/2/15 12:18 PM 2 Notice and Warning Concerning U.S. Patent or Trademark Rights The inclusion in the USP Dietary Supplements Compendium of a monograph on any dietary supplement in respect to which patent or trademark rights may exist shall not be deemed, and is not intended as, a grant of, or authority to exercise, any right or privilege protected by such patent or trademark. All such rights and privileges are vested in the patent or trademark owner, and no other person may exercise the same without express permission, authority, or license secured from such patent or trademark owner. Concerning Use of the USP Dietary Supplements Compendium Attention is called to the fact that USP Dietary Supplements Compendium text is fully copyrighted. Authors and others wishing to use portions of the text should request permission to do so from the Legal Department of the United States Pharmacopeial Convention. Copyright © 2015 The United States Pharmacopeial Convention ISBN: 978-1-936424-41-2 12601 Twinbrook Parkway, Rockville, MD 20852 All rights reserved. DSC Contents iii Contents USP Dietary Supplements Compendium Volume 1 Volume 2 Members . v. Preface . v Mission and Preface . 1 Dietary Supplements Admission Evaluations . 1. General Notices and Requirements . 9 USP Dietary Supplement Verification Program . .205 USP–NF General Chapters . 25 Dietary Supplements Regulatory USP–NF Dietary Supplement Monographs . -

Nutritional Value of Spirulina and Its Use in the Preparation of Some Complementary Baby Food Formulas

Available online at http://journal-of-agroalimentary.ro Journal of Agroalimentary Processes and Journal of Agroalimentary Processes and Technologies Technologies 2014, 20(4), 330-350 Nutritional value of spirulina and its use in the preparation of some complementary baby food formulas Ashraf M. Sharoba Food Sci. Dept., Fac. of Agric., Moshtohor, Benha Univ., Egypt Received: 26 September 2014; Accepted:03 Octomber 2014 .____________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract In this study use the spirulina which is one of the blue-green algae rich in protein 62.84% and contains a high proportion of essential amino acids (38.46% of the protein) and a source of naturally rich in vitamins especially vitamin B complex such as vitamin B12 (175 µg / 10 g) and folic acid (9.92 mg / 100 g), which helps the growth and nutrition of the child brain, also rich in calcium and iron it containing (922.28 and 273.2 mg / 100 g, respectively) to protect against osteoporosis and blood diseases as well as a high percentage of natural fibers. So, the spirulina is useful and necessary for the growth of infants and very suitable for children, especially in the growth phase, the elderly and the visually appetite. It also, helps a lot in cases of general weakness, anemia and chronic constipation. Spirulina contain an selenium element (0.0393 mg/100 g) and many of the phytopigments such as chlorophyll and phycocyanin (1.56% and 14.647%), and those seen as a powerful antioxidant. Finally, spirulina called the ideal food for mankind and the World Health Organization considered its "super food" and the best food for the future because of its nutritional value is very high. -

Spectrumneedstm, a New Comprehensive Nutritional Therapy for Autism, Functional Conditions, and Mitochondrial Disease

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX SpectrumNeedsTM, a New Comprehensive Nutritional Therapy for Autism, Functional Conditions, and Mitochondrial Disease Richard G. Boles, M.D. Chief Medical & Scientific Officer NeuroNeeds LLC Director, CNNH NeuroGenomics Program [telemedicine] Medical Geneticist in Private Practice Faculty Advisor, MitoAction MitoAction Webinar April 6, 2018 XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Disclosure: XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Dr. Boles wears many hats XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX • Chief Medical & Scientific Officer of NeuroNeeds LLC – Present: The company that produces SpectrumNeedsTM (https://neuroneeds.com) • Medical Director for DNA Sequencing Companies – Past: 5 years at Courtagen Life Sciences; 6 months at Lineagen – Present: Loose affiliations with some companies – Roles: Test development, testing, interpretation, marketing • Researcher with prior NIH and foundation funding – Past: USC faculty for 20 years – Present: Study sequence variation that predispose towards neurodevelopmental and functional disorders • Clinician treating patients – Primary interests in functional disease (autism, cyclic vomiting) – Past: Geneticist/pediatrician 20 years at CHLA/USC – Present: In private practice since 2014 (http://molecularmitomd.com) – Present: Telemedicine as part of CNNH NeuroGenomics Program (https://cnnh.org) XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX -

Biomarkers of Nutrition for Development—Iodine Review1–4

Supplemental Material can be found at: http://jn.nutrition.org/content/suppl/2014/06/25/jn.113.18197 4.DCSupplemental.html The Journal of Nutrition Supplement: Biomarkers of Nutrition for Development (BOND) Expert Panel Reviews, Part 1 Biomarkers of Nutrition for Development—Iodine Review1–4 Fabian Rohner,5,6,15 Michael Zimmermann,7,8,15 Pieter Jooste,9,10,15 Chandrakant Pandav,11,12,15 Kathleen Caldwell,13,15 Ramkripa Raghavan,14 and Daniel J. Raiten14* 5Groundwork LLC, Crans-pre`s-Celigny,´ Switzerland; 6Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN), Geneva, Switzerland; 7Institute of Food, Nutrition and Health, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), Zurich, Switzerland; 8The International Council for the Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders (ICCIDD) Global Network, Zurich, Switzerland; 9Centre of Excellence for Nutrition, Faculty of Health Sciences, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa; 10Southern Africa Office, The ICCIDD Global Network, Capetown, South Africa; 11Centre for Community Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India; 12South Asia Office, The ICCIDD Global Network, New Delhi, India; 13National Center for Environmental Health, CDC, Atlanta, GA; and 14Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, Bethesda, MD Downloaded from Abstract The objective of the Biomarkers of Nutrition for Development (BOND) project is to provide state-of-the-art information and service with regard to selection, use, and interpretation of biomarkers of nutrient exposure, status, function, and effect. Specifically, the BOND project seeks to develop consensus on accurate assessment methodologies that are applicable to researchers (laboratory/clinical/surveillance), clinicians, programmers, and policy makers (data consumers). The BOND jn.nutrition.org project is also intended to develop targeted research agendas to support the discovery and development of biomarkers through improved understanding of nutrient biology within relevant biologic systems. -

Vitamin a Deficiency Modifies Lipid Metabolism in Rat Liver

Downloaded from British Journal of Nutrition (2007), 97, 263–272 DOI: 10.1017/S0007114507182659 q The Authors 2007 https://www.cambridge.org/core Vitamin A deficiency modifies lipid metabolism in rat liver Liliana B. Oliveros, Marı´a A. Domeniconi, Vero´nica A. Vega, Laura V. Gatica, Ana M. Brigada and Marı´a S. Gimenez* . IP address: Laboratory of Biological Chemistry, Faculty of Chemistry, Biochemistry and Pharmacy, National University of San Luis, Avenida Eje´rcito de los Andes 954, 5700 San Luis, Argentina 170.106.33.22 (Received 11 January 2006 – Revised 24 May 2006 – Accepted 8 June 2006) , on Liver fatty acid metabolism of male rats fed on a vitamin A-deficient diet for 3 months from 21 d of age was evaluated. Vitamin A restriction 01 Oct 2021 at 13:42:02 produced subclinical plasma and negligible liver retinol concentrations, compared with the control group receiving the same diet with 4000 IU vitamin A (8 mg retinol as retinyl palmitate)/kg diet. Vitamin A deficiency induced a hypolipidaemic effect by decreasing serum triacylglycerol, cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol levels. The decrease of liver total phospholipid was associated with low phosphatidylcholine synthesis observed by lower [14C]choline incorporation into phosphatidylcholine, compared with control. Also, liver fatty acid synthesis decreased, as was indicated by activity and mRNA expression of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), and incorporation of [14C]acetate into saponified lipids. A decrease of the PPARa mRNA expression was observed. Liver mitochondria of vitamin A-deficient rats showed a lower total phospholipid concentration coinciding with a decrease of the cardiolipin proportion, without changes in the other phospholipid fractions determined. -

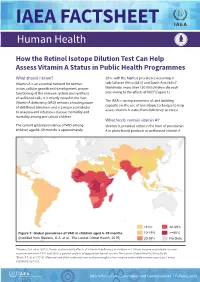

IAEA Factsheet: How the Retinol Isotope Dilution Test Can Help

IAEA FACTSHEET Human Health How the Retinol Isotope Dilution Test Can Help Assess Vitamin A Status in Public Health Programmes What should I know? 29%, with the highest prevalence occurring in Vitamin A is an essential nutrient for normal sub-Saharan Africa (48%) and South Asia (44%)1. vision, cellular growth and development, proper Worldwide, more than 150 000 children die each functioning of the immune system and synthesis year owing to the effects of VAD2 [Figure 1]. of red blood cells. It is mostly stored in the liver. The IAEA is raising awareness of, and building Vitamin A deficiency (VAD) remains a leading cause capacity on, the use of an isotopic technique to help of childhood blindness and is a major contributor assess vitamin A status from deficiency to excess. to anaemia and infectious disease morbidity and mortality among pre-school children. What foods contain vitamin A? The current global prevalence of VAD among Vitamin A, provided either in the form of provitamin children aged 6–59 months is approximately A in plant-based products or preformed vitamin A <10% 40-59% Figure 1: Global prevalence of VAD in children aged 6–59 months 10-19% >=60% (modified from Stevens, G.A. et al., The Lancet Global Health, 2015) 20-39% No Data 1Stevens, G.A. et al. (2015). Trends and mortality effects of vitamin A deficiency in children in 138 low-income and middle-income countries between 1991 and 2013: a pooled analysis of population-based surveys. The Lancet Global Health 3(9):e528-36. 2Black, R.E. -

Nutrition Journal of Parenteral and Enteral

Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition http://pen.sagepub.com/ Micronutrient Supplementation in Adult Nutrition Therapy: Practical Considerations Krishnan Sriram and Vassyl A. Lonchyna JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2009 33: 548 originally published online 19 May 2009 DOI: 10.1177/0148607108328470 The online version of this article can be found at: http://pen.sagepub.com/content/33/5/548 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: The American Society for Parenteral & Enteral Nutrition Additional services and information for Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition can be found at: Email Alerts: http://pen.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://pen.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - Aug 27, 2009 OnlineFirst Version of Record - May 19, 2009 What is This? Downloaded from pen.sagepub.com by Karrie Derenski on April 1, 2013 Review Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Volume 33 Number 5 September/October 2009 548-562 Micronutrient Supplementation in © 2009 American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 10.1177/0148607108328470 Adult Nutrition Therapy: http://jpen.sagepub.com hosted at Practical Considerations http://online.sagepub.com Krishnan Sriram, MD, FRCS(C) FACS1; and Vassyl A. Lonchyna, MD, FACS2 Financial disclosure: none declared. Preexisting micronutrient (vitamins and trace elements) defi- for selenium (Se) and zinc (Zn). In practice, a multivitamin ciencies are often present in hospitalized patients. Deficiencies preparation and a multiple trace element admixture (containing occur due to inadequate or inappropriate administration, Zn, Se, copper, chromium, and manganese) are added to par- increased or altered requirements, and increased losses, affect- enteral nutrition formulations. -

Vitamin a Deficiency Modifies Lipid Metabolism in Rat Liver

Abstract Br J Nutr. 2007 Feb;97(2):263-72. Vitamin A deficiency modifies lipid metabolism in rat liver. Oliveros LB, Domeniconi MA, Vega VA, Gatica LV, Brigada AM, Gimenez MS. Laboratory of Biological Chemistry, Faculty of Chemistry, Biochemistry and Pharmacy, National University of San Luis, Avenida Ejército de los Andes 954, 5700 San Luis, Argentina. OBJECTIVE AND METHODS: Liver fatty acid metabolism of male rats fed on a vitamin A- deficient diet for 3 months from 21 d of age was evaluated. RESULTS: Vitamin A restriction produced subclinical plasma and negligible liver retinol concentrations, compared with the control group receiving the same diet with 4000 IU vitamin A (8 mg retinol as retinyl palmitate)/kg diet. Vitamin A deficiency induced a hypolipidaemic effect by decreasing serum triacylglycerol, cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol levels. The decrease of liver total phospholipid was associated with low phosphatidylcholine synthesis observed by lower [14C]choline incorporation into phosphatidylcholine, compared with control. Also, liver fatty acid synthesis decreased, as was indicated by activity and mRNA expression of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), and incorporation of [14C]acetate into saponified lipids. A decrease of the PPARalpha mRNA expression was observed. Liver mitochondria of vitamin A-deficient rats showed a lower total phospholipid concentration coinciding with a decrease of the cardiolipin proportion, without changes in the other phospholipid fractions determined. The mitochondria fatty acid oxidation increased by 30 % of the control value and it was attributed to a high activity and mRNA expression of carnitine palmitoyltransferase-I (CPT-I). An increase in serum beta- hydroxybutyrate levels was observed in vitamin A-deficient rats. -

Disturbed Vitamin a Metabolism in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)

nutrients Review Disturbed Vitamin A Metabolism in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Ali Saeed 1,2, Robin P. F. Dullaart 3, Tim C. M. A. Schreuder 1, Hans Blokzijl 1 and Klaas Nico Faber 1,4,* 1 Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, 9713 GZ Groningen, The Netherlands; [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (T.C.M.A.S.); [email protected] (H.B.) 2 Institute of Molecular Biology & Bio-Technology, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan 60800, Pakistan 3 Department of Endocrinology, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, 9713 GZ Groningen, The Netherlands; [email protected] 4 Department of Laboratory Medicine, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, 9713 GZ Groningen, The Netherlands * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +31-(0)5-0361-2364; Fax: +31-(0)5-0361-9306 Received: 7 November 2017; Accepted: 19 December 2017; Published: 29 December 2017 Abstract: Vitamin A is required for important physiological processes, including embryogenesis, vision, cell proliferation and differentiation, immune regulation, and glucose and lipid metabolism. Many of vitamin A’s functions are executed through retinoic acids that activate transcriptional networks controlled by retinoic acid receptors (RARs) and retinoid X receptors (RXRs).The liver plays a central role in vitamin A metabolism: (1) it produces bile supporting efficient intestinal absorption of fat-soluble nutrients like vitamin A; (2) it produces retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4) that distributes vitamin A, as retinol, to peripheral tissues; and (3) it harbors the largest body supply of vitamin A, mostly as retinyl esters, in hepatic stellate cells (HSCs).