ABBOTT V. PEREZ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Alabama School Girl in Paris 1842-1844

An Alabama School Girl in Paris 1842-1844 the letters of Mary Fenwick Lewis and her family Nancyt/ M. Rohr_____ _ An Alabama School Girl in Paris, 1842-1844 The Letters of Mary Fenwick Lewis and Her Family Edited by Nancy M. Rohr An Alabama School Girl In Paris N a n c y M. Ro h r Copyright Q 2001 by Nancy M. Rohr All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission of the editor. ISPN: 0-9707368-0-0 Silver Threads Publishing 10012 Louis Dr. Huntsville, AL 35803 Second Edition 2006 Printed by Boaz Printing, Boaz, Alabama CONTENTS Preface...................................................................................................................1 EditingTechniques...........................................................................................5 The Families.......................................................................................................7 List of Illustrations........................................................................................10 I The Lewis Family Before the Letters................................................. 11 You Are Related to the Brave and Good II The Calhoun Family Before the Letters......................................... 20 These Sums will Furnish Ample Means Apples O f Gold in Pictures of Silver........................................26 III The Letters - 1842................................................................................. 28 IV The Letters - 1843................................................................................ -

John Ellis Full Biog 2018

JOHN ELLIS BULLET BIOG 2018 Formed the legendary BAZOOKA JOE Band members included Adam Ant. First Sex Pistols gig was as support to Bazooka Joe. A very influential band despite making no records. Formed THE VIBRATORS. Released 2 albums for Epic. Also played with Chris Spedding on TV and a couple of shows. REM covered a Vibrators single. Extensive touring and TV/Radio appearances including John Peel sessions. Released 2 solo singles. Played guitar in Jean-Jacques Burnel’s Euroband for UK tour. Formed RAPID EYE MOVEMENT featuring HOT GOSSIP dancers and electronics. Supported Jean-Jacques Burnel’s Euroband on UK tour. Joined Peter Gabriel Band for “China” tour and played on Gabriel’s 4th solo album. Stood in for Hugh Cornwell for 2 shows by THE STRANGLERS at the Rainbow Theatre. Album from gig released. Worked with German duo ISLO MOB on album and single. Started working with Peter Hammill eventually doing many tours and recording on 7 albums. Rejoined THE VIBRATORS for more recording and touring. Founder and press officer for the famous M11 Link Road campaign. Recorded 2 albums under the name of PURPLE HELMETS with Jean-Jacques Burnel and Dave Greenfield of THE STRANGLERS. Played additional guitar on THE STRANGLERS ‘10’ tour. Joined THE STRANGLERS as full time member. Extensive touring and recording over 10 years. Many albums released including live recording of Albert Hall show. Played many festivals across the world. Many TV and Radio appearances. Started recording series of electronic instrumental albums as soundtracks for Art exhibitions. 5 CDs released by Voiceprint. Also released WABI SABI 21©, the first of a trilogy of albums inspired by Japanese culture. -

Les Archives Du Sombre Et De L'expérimental

Guts Of Darkness Les archives du sombre et de l'expérimental avril 2006 Vous pouvez retrouvez nos chroniques et nos articles sur www.gutsofdarkness.com © 2000 - 2008 Un sommaire de ce document est disponible à la fin. Page 2/249 Les chroniques Page 3/249 ENSLAVED : Frost Chronique réalisée par Iormungand Thrazar Premier album du groupe norvégien chz le label français Osmose Productions, ce "Frost" fait suite au début du groupe avec "Vikingligr Veldi". Il s'agit de mon album favori d'Enslaved suivi de près par "Eld", on ressent une envie et une virulence incroyables dans cette oeuvre. Enslaved pratique un black metal rageur et inspiré, globalement plus violent et ténébreux que sur "Eld". Il n'y a rien à jeter sur cet album, aucune piste de remplissage. On commence après une intro aux claviers avec un "Loke" ravageur et un "Fenris" magnifique avec son riff à la Satyricon et son break ultra mélodique. Enslaved impose sa patte dès 1994, avec la très bonne performance de Trym Torson à la batterie sur cet album, qui s'en ira rejoindre Emperor par la suite. "Svarte vidder" est un grand morceau doté d'une intro symphonique, le développement est excellent, 9 minutes de bonheur musical et auditif. "Yggdrasill" se pose en interlude de ce disque, un titre calme avec voix grave, guimbarde, choeurs et l'utilisation d'une basse fretless jouée par Eirik "Pytten", le producteur de l'album: un intemrède magnifique et judicieux car l'album gagne en aération. Le disque enchaîne sur un "Jotu249lod" destructeur et un Gylfaginning" accrocheur. -

Republican Appointees and Judicial Discretion: Cases Studies from the Federal Sentencing Guidelines Era

Republican Appointees and Judicial Discretion: Cases Studies From the Federal Sentencing Guidelines Era Professor David M. Zlotnicka Senior Justice Fellow – Open Society Institute Nothing sits more uncomfortably with judges than the sense that they have all the responsibility for sentencing but little of the power to administer it justly.1 Outline of the Report This Report explores Republican-appointed district court judge dissatisfaction with the sentencing regime in place during the Sentencing Guideline era.2 The body of the Report discusses my findings. Appendix A presents forty case studies which are the product of my research.3 Each case study profiles a Republican appointee and one or two sentencings by that judge that illustrates the concerns of this cohort of judges. The body of the Report is broken down as follows: Part I addresses four foundational issues that explain the purposes and relevance of the project. Parts II and III summarizes the broad arc of judicial reaction to aThe author is currently the Distinguished Service Professor of Law, Roger Williams University School of Law, J.D., Harvard Law School. During 2002-2004, I was a Soros Senior Justice Fellow and spent a year as a Visiting Scholar at the George Washington University Law Center and then as a Visiting Professor at the Washington College of Law. I wish to thank OSI and these law schools for the support and freedom to research and write. Much appreciation is also due to Dan Freed, Ian Weinstein, Paul Hofer, Colleen Murphy, Jared Goldstein, Emily Sack, and Michael Yelnosky for their helpful c omments on earlier drafts of this Report and the profiles. -

Fighting Injustice

Fighting Injustice by Michael E. Tigar Copyright © 2001 by Michael E. Tigar All rights reserved CONTENTS Introduction 000 Prologue It Doesn’t Get Any Better Than This 000 Chapter 1 The Sense of Injustice 000 Chapter 2 What Law School Was About 000 Chapter 3 Washington – Unemployment Compensation 000 Chapter 4 Civil Wrongs 000 Chapter 5 Divisive War -- Prelude 000 Chapter 6 Divisive War – Draft Board Days and Nights 000 Chapter 7 Military Justice Is to Justice . 000 Chapter 8 Chicago Blues 000 Chapter 9 Like A Bird On A Wire 000 Chapter 10 By Any Means Necessary 000 Chapter 11 Speech Plus 000 Chapter 12 Death – And That’s Final 000 Chapter 13 Politics – Not As Usual 000 Chapter 14 Looking Forward -- Changing Direction 000 Appendix Chronology 000 Afterword 000 SENSING INJUSTICE, DRAFT OF 7/11/13, PAGE 2 Introduction This is a memoir of sorts. So I had best make one thing clear. I am going to recount events differently than you may remember them. I will reach into the stream of memory and pull out this or that pebble that has been cast there by my fate. The pebbles when cast may have had jagged edges, now worn away by the stream. So I tell it as memory permits, and maybe not entirely as it was. This could be called lying, but more charitably it is simply what life gives to each of us as our memories of events are shaped in ways that give us smiles and help us to go on. I do not have transcripts of all the cases in the book, so I recall them as well as I can. -

'Curly's Airships' in One Way Or Another

The Songstory by Judge Smith Home | Buy Now! Contents | Previous | Next CURLY'S AIRSHIPS is an epic work of words and music about the R.101 airship disaster of 1930, written in a new form of narrative rock music called songstory. This double CD involves eighteen featured performers, among whom are four of the original members of Van der Graaf Generator, including respected solo artist Peter Hammill and the composer of Curly's Airships, Judge Smith. Also participating are singer Arthur Brown (of The Crazy World), Pete Brown (of Battered Ornaments and Piblokto), Paul Roberts (of The Stranglers), John Ellis, (formerly of The Vibrators and The Stranglers), plus a 1920’s dance band, a classical Tenor, an Indian music ensemble and several cathedral organs. Six years in the making, Curly's Airships is probably one of the largest and most ambitious single pieces of rock music ever recorded. CONTACT US: To contact us on all matters, Email [email protected] Copyright © 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005 Judge Smith. All Rights Reserved World Wide. Last updated on Navigation Home | Buy Now! Contents | Previous | Next CURLY'S AIRSHIPS tells the true story of the bizarre events which led to the destruction of the world’s biggest airship, the giant dirigible R.101, on its maiden voyage to India; a tale of the incompetence and arrogance of government bureaucrats, the ruthless ambition of a powerful politician and the moral cowardice of his juniors; a story of inexplicable psychic phenomena, the thoughtless bravery of 1920s aviators and the extraordinary spell cast by the gigantic machines they flew: the giant airships, the most surreal and dreamlike means of transport ever devised. -

Study 12: Joint Ownership of Copyrights

86th congress} CO~TTEE PB~T 2d Session COPYRIGHT LAW REVISION STUDIES PREPARED FOR THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON PATENTS, TRADEMARKS, AND COPYRIGHTS OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE EIGHTY-SIXTH CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION PURBUANTTO S. Res. 240 STUDIES 11-13 12. Joint Ownership of Copyrlghta Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1960 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JAMES O. EASTLAND, Mississippi, C'1I4lrman ESTES KEFAUVER, Tennessee ALEXANDER WILEY, Wisconsin , OLIN D. JOHNSTON, South Carolina EVERETT McKINLEY DIRKSEN, IJIlnols THOMAS C. HENNINGS, JR., Missouri ROMAN L. HRUSKA, Nebraska JOHN L. McCLELLAN, Arkansas KENNETH B. KEATING, New York JOSEPH C. O'MAHONEY, Wyoming NORRIS COTTON, New Hampshire SAM J. ERVIN, JR., Nortb Carolina JOHN A. CARROLL, Colorado THOMAS J. DODD, Connecticut PHILIP A. HART, Michigan SUBCOMMITTEE ON PATENTS, TRADEMARKS, AND COPYRIGHTS JOSEPH C. O'MAHONEY, Wyoming, C'1I4lrman OLIN D. JOHNSTON, South Carolina ALEXANDER WILEY, Wisconsin PHILIP A. HART, Michigan ROBIlRT L. WRIGHT, Chief Counlel JOHN C. STIlDMAN, Aleoclate Cotl1l8el STIlPHIlN G. HAASIlR, Chief Clerk II FOREWORD This committee print is the fourth of a series of such prints of studies on Copyright Law Revision published by the Oommittee on the Judiciary Subcommittee on Patents, Trademarks and Copyrights. The studies have been prepared under the supervision of the Copyright Office of the Library of Congress with a view to considering a general revision of the copyright law (title 17, United States Code). Provisions of the present copyright law are essentially the same as those of the statutes enacted in 1909, though that statute was codified in 1947 and has been amended in a number of relatively minor respects. -

Reunification

THE OLD OUNDELIAN 2019-2020 Iain Farrington Brian Hemingway REUNIFICATION ( C 95 ) on pop ( St A 70 ) writes On the tenth anniversary of the formal and jazz, Horrible about his father, unification of Oundle School and Laxton Histories, and Paddy, the last School, Philip Sloan ( LS 71 ) gives a making classical surviving Battle of historical perspective music accessible to all Britain fighter pilot OFFICERS The Old Oundelian Club PRESIDENT: Charles Miller ( Ldr 76 ) SECRETARY, TREASURER AND LONDON DINNER SECRETARY: Jane Fenton ADDRESS: The Stables, Cobthorne, West Street, Oundle PE8 4EF. TEL: 01832 277297. EMAIL: [email protected] VICE PRESIDENTS Mary Price ( K 94 ) Hon Sec OO Women’s Hockey Alastair Irvine ( Sc 81 ) Nina Rieck ( K 95 ) Alice Rockall ( W 12 ) Chris Piper ( Sc 71 ) Email: [email protected] SPORTS SECRETARIES LIFE VICE PRESIDENTS Hon Sec Oundle Rovers CC Hon Sec Netball Nick Cheatle ( G 63 ) Chris Piper ( Sc 71 ) Rachel Hawkesford ( W 08 ) John Crabbe ( G 55 ) Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Shane Dodd ( Sn 74 ) Hon Sec OORUFC Robert Ellis ( D 65 ) Hon Sec OO Rifle Club Sam Cone ( St A 05 ) Sir Michael Pickard ( C 51 ) Charles Shelley ( S 18 ) Email: [email protected] Chris Piper ( Sc 71 ) Email: [email protected] Chris Walliker ( D 54 ) Hon Sec OO Golfing Society Hon Sec OO Rowing Club Harry Williamson ( St A 55 ) James Aston ( St A 92 ) Kristina Cowley ( L 13 ) Email: [email protected] FINANCE AND POLICY COMMITTEE Email: [email protected] Alastair Irvine ( Sc -

A Report on the Bay Area Complex Litigation Superior Courts

A Report on the Bay Area Complex Litigation Superior Courts By Frank Burke, Chandra S. Russell, Stephanie D. Biehl, Adam R. Brausa, Adrian Canzoneri, Shana Inspektor, Kapri L. Saunders, and Ashley L. Shively Winter 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW .......................................................................................1 PART II: INTERVIEW SUMMARIES .................................................................................................11 San Francisco County Superior Court .................................................................................12 Interview of Hon. Mary E. Wiss ...................................................................................13 Interview of Hon. Curtis E.A. Karnow ..........................................................................19 San Mateo County Superior Court .....................................................................................25 Interview of Hon. Marie S. Weiner ..............................................................................26 Santa Clara County Superior Court ....................................................................................35 Interview of Hon. Brian C. Walsh ...............................................................................36 Interview of Hon. Thomas E. Kuhnle ...........................................................................42 Alameda County Superior Court ........................................................................................46 Interview of Hon. -

Domingo Junta Plans New Attacks

, Weather I If *my itetfagr, Ugh 71. Pair THEDAEY tnltf*, low In the Mi. T«mt> X nw, variable clooduKU, bi(h is Red Bank Area 25,475 (be 7J». Thursday, ekxMty, be- 7 Copyright—The Red Bank Register, Inc., 1965. coming fair and warm. See DIAL 741-0010 weather, page 2. MONMOUTH COUNTY'S HOME NEWSPAPER FOR 87 YEARS Hiutd dtllr. XoaUjr Urouth nidur. Beeocl Clui Poiuj* VOL, 87, NO. 229 PUd tt Mil Bulk ind U AUlllonU Mllllnt Olflcei. TUESDAY, MAY 18, 1965 7c PER COPY PAGE ONE Domingo Junta Plans New Attacks SANTO DOMINGO, Dominican Republican (AP) — The Guzman was known to be acceptable to the rebel regime in the Dominican Republic," said Ambassador Ricardo Colombo crossing the President Peynado Bridge over the Isabella River. - Dominican junta today poised the threat of an all-out drive headed by Col. Francisco Caamano Deno. The rebels originally of Argentina. They set up a line west of the rebels near the Quisqueya baso-i against the rebels after rejecting a new peace plan offered by sought the return of Bosch and of the constitution which was Accompanying the OAS mission was Jack Hood Vaughn, an ball stadium and began pressing eastward. •: Washington. junked when the military overthrew him. assistant secretary of state for inter-American affairs who went To escape, the rebels had to hide their weapons and pass As the junta sent tanks and fresh troops with mortars and Imbert oalled Gutman a "Bosch puppet." He said he re- to Santo Domingo with Bundy. through a U.S. checkpoint into the downtown rebel area ot try : artillery against rebel holdouts in northern Santo Domingo, minded the U.S. -

Divergence Between the UK and USA 245 JOINT AUTHORSHIP in COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE: LEVY V

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\62-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 1 13-JUL-15 16:08 Divergence Between the UK and USA 245 JOINT AUTHORSHIP IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE: LEVY V. RUTLEY AND DIVERGENCE BETWEEN THE UK AND USA by ELENA COOPER* Recent scholarship has pointed to the diversity of copyright, and in- tellectual property laws more generally, in the common law world. In the place of a picture of convergence and uniformity, in The Common Law of Intellectual Property, Catherine Ng, Lionel Bently and Giuseppina D’Agostino argue that the “commonality” of intellectual property laws in common law jurisdictions has “latterly . become increasingly fractured.” As they observe, drawing together a series of essays, the cumulative effect of diversity in many aspects of intellectual property law supports the “the- sis of growing divergence in the approaches taken by the courts and legis- latures of various common law countries”; the result is “a strong case that the approaches taken in the common law countries are anything but common.”1 A copyright doctrine left unconsidered by The Common Law of Intel- lectual Property is joint authorship. A number of developments in this area point to legal variation across common law jurisdictions in recent times.2 Amongst these are judicial decisions in the UK and the U.S., *Junior Research Fellow, Trinity Hall, Cambridge and Research Fellow in Copy- right Law, History and Policy, CREATe Copyright Centre, University of Glasgow. The author benefitted from discussions that formed part of the Research Council funded project Of Authorship and Originality in particular with the other two members of the Cambridge University team, Lionel Bently and Laura Biron, and with Stefan Van Gompel while the author was a visiting scholar at IVIR, Univer- sity of Amsterdam in 2012. -

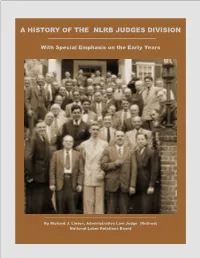

View a History of the Division of Judges (Pdf)

A HISTORY OF THE NLRB JUDGES DIVISION With Special Emphasis on the Early Years By Richard J. Linton, Administrative Law Judge (Retired) National Labor Relations Board A HISTORY OF THE NLRB JUDGES DIVISION With Special Emphasis on the Early Years BY RICHARD J. LINTON. ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE (RETIRED) NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS BOARD August 1, 2004 COVER PICTURE The cover picture is a copy of the one taken of attendees at the May 1942 Trial Examiners Conference in Annapolis, Maryland. This photograph is reproduced, and the attendees are discussed, beginning at page 58. As there explained, Phoebe Smith Ruckle, of Charleston, West Virginia, graciously supplied a copy for this paper. Her grandfather, Judge Edward Grandison Smith, is one of the judges in the picture. Credit for the inspired thought of placing a copy of the photograph on the cover goes to David B. Parker, the NLRB’s Deputy Executive Secretary. DEDICATION In grateful memory of the early-day judges of the National Labor Relations Board. They labored when the sun was high, the winds hot, and the honors few. The rest of us have followed in relative comfort, security, and respect. PUBLICATION DATE In this year of 2004, the August 1 publication date of this book is chosen to mark the 66th anniversary of the decision by the Board to switch, effective August 1, 1938, from a system of hiring most of its judges (“Trial Examiners,” then) as day laborers (“per diem” judges), to a system of employing us as regular-staff salaried employees of the Federal Government. This book was printed by the NLRB in October 2004.