Other Matters Then Pend- Ing; and Such Emergency Matters As May Be Submitted by the Governor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Policy Report Texas Fact Book 2010

Texas Fact Book 2010 Legislative Budget Board LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD EIGHTY-FIRST TEXAS LEGISLATURE 2009 – 2010 DAVID DEWHURST, JOINT CHAIR Lieutenant Governor JOE STRAUS, JOINT CHAIR Representative District 121, San Antonio Speaker of the House of Representatives STEVE OGDEN Senatorial District 5, Bryan Chair, Senate Committee on Finance ROBERT DUNCAN Senatorial District 28, Lubbock JOHN WHITMIRE Senatorial District 15, Houston JUDITH ZAFFIRINI Senatorial District 21, Laredo JIM PITTS Representative District 10, Waxahachie Chair, House Committee on Appropriations RENE OLIVEIRA Representative District 37, Brownsville Chair, House Committee on Ways and Means DAN BRANCH Representative District 108, Dallas SYLVESTER TURNER Representative District 139, Houston JOHN O’Brien, Director COVER PHOTO COURTESY OF HOUSE PHOTOGRAPHY CONTENTS STATE GOVERNMENT STATEWIDE ELECTED OFFICIALS . 1 MEMBERS OF THE EIGHTY-FIRST TEXAS LEGISLATURE . 3 The Senate . 3 The House of Representatives . 4 SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES . 8 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEES . 10 BASIC STEPS IN THE TEXAS LEGISLATIVE PROCESS . 14 TEXAS AT A GLANCE GOVERNORS OF TEXAS . 15 HOW TEXAS RANKS Agriculture . 17 Crime and Law Enforcement . 17 Defense . 18 Economy . 18 Education . 18 Employment and Labor . 19 Environment and Energy . 19 Federal Government Finance . 20 Geography . 20 Health . 20 Housing . 21 Population . 21 Science and Technology . 22 Social Welfare . 22 State and Local Government Finance . 22 Transportation . 23 Border Facts . 24 STATE HOLIDAYS, 2010 . 25 STATE SYMBOLS . 25 POPULATION Texas Population Compared with the U .s . 26 Texas and the U .s . Annual Population Growth Rates . 27 Resident Population, 15 Most Populous States . 28 Percentage Change in Population, 15 Most Populous States . 28 Texas Resident Population, by Age Group . -

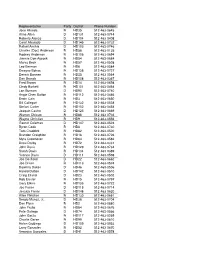

82Nd Leg Members

Representative Party District Phone Number Jose Aliseda R HD35 512-463-0645 Alma Allen D HD131 512-463-0744 Roberto Alonzo D HD104 512-463-0408 Carol Alvarado D HD145 512-463-0732 Rafael Anchia D HD103 512-463-0746 Charles (Doc) Anderson R HD56 512-463-0135 Rodney Anderson R HD106 512-463-0694 Jimmie Don Aycock R HD54 512-463-0684 Marva Beck R HD57 512-463-0508 Leo Berman R HD6 512-463-0584 Dwayne Bohac R HD138 512-463-0727 Dennis Bonnen R HD25 512-463-0564 Dan Branch R HD108 512-463-0367 Fred Brown R HD14 512-463-0698 Cindy Burkett R HD101 512-463-0464 Lon Burnam D HD90 512-463-0740 Angie Chen Button R HD112 512-463-0486 Erwin Cain R HD3 512-463-0650 Bill Callegari R HD132 512-463-0528 Stefani Carter R HD102 512-463-0454 Joaquin Castro D HD125 512-463-0669 Warren Chisum R HD88 512-463-0736 Wayne Christian R HD9 512-463-0556 Garnet Coleman D HD147 512-463-0524 Byron Cook R HD8 512-463-0730 Tom Craddick R HD82 512-463-0500 Brandon Creighton R HD16 512-463-0726 Myra Crownover R HD64 512-463-0582 Drew Darby R HD72 512-463-0331 John Davis R HD129 512-463-0734 Sarah Davis R HD134 512-463-0389 Yvonne Davis D HD111 512-463-0598 Joe Deshotel D HD22 512-463-0662 Joe Driver R HD113 512-463-0574 Dawnna Dukes D HD46 512-463-0506 Harold Dutton D HD142 512-463-0510 Craig Eiland D HD23 512-463-0502 Rob Eissler R HD15 512-463-0797 Gary Elkins R HD135 512-463-0722 Joe Farias D HD118 512-463-0714 Jessica Farrar D HD148 512-463-0620 Allen Fletcher R HD130 512-463-0661 Sergio Munoz, Jr. -

STANDING COMMITTEES of the HOUSE Agriculture

STANDING COMMITTEES OF THE HOUSE [Democrats in roman; Republicans in italic; Resident Commissioner and Delegates in boldface] [Room numbers beginning with H are in the Capitol, with CHOB in the Cannon House Office Building, with LHOB in the Longworth House Office Building, with RHOB in the Rayburn House Office Building, with H1 in O’Neill House Office Building, and with H2 in the Ford House Office Building] Agriculture 1301 Longworth House Office Building, phone 225–2171, fax 225–8510 http://agriculture.house.gov meets first Wednesday of each month Collin C. Peterson, of Minnesota, Chair Tim Holden, of Pennsylvania. Bob Goodlatte, of Virginia. Mike McIntyre, of North Carolina. Terry Everett, of Alabama. Bob Etheridge, of North Carolina. Frank D. Lucas, of Oklahoma. Leonard L. Boswell, of Iowa. Jerry Moran, of Kansas. Joe Baca, of California. Robin Hayes, of North Carolina. Dennis A. Cardoza, of California. Timothy V. Johnson, of Illinois. David Scott, of Georgia. Sam Graves, of Missouri. Jim Marshall, of Georgia. Jo Bonner, of Alabama. Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, of South Dakota. Mike Rogers, of Alabama. Henry Cuellar, of Texas. Steve King, of Iowa. Jim Costa, of California. Marilyn N. Musgrave, of Colorado. John T. Salazar, of Colorado. Randy Neugebauer, of Texas. Brad Ellsworth, of Indiana. Charles W. Boustany, Jr., of Louisiana. Nancy E. Boyda, of Kansas. John R. ‘‘Randy’’ Kuhl, Jr., of New York. Zachary T. Space, of Ohio. Virginia Foxx, of North Carolina. Timothy J. Walz, of Minnesota. K. Michael Conaway, of Texas. Kirsten E. Gillibrand, of New York. Jeff Fortenberry, of Nebraska. Steve Kagen, of Wisconsin. Jean Schmidt, of Ohio. -

2012 Election Preview: the Projected Impact on Congressional Committees

2012 Election Preview: the Projected Impact on Congressional Committees K&L Gates LLP 1601 K Street Washington, DC 20006 +1.202.778.9000 October 2012 Table of Contents Table of Contents 1-2 Introduction 3 House Key Code 4 House Committee on Administration 5 House Committee on Agriculture 6 House Committee on Appropriations 7 House Committee on Armed Services 8 House Committee on the Budget 9 House Committee on Education and the Workforce 10 House Committee on Energy and Commerce 11 House Committee on Ethics 12 House Committee on Financial Services 13 House Committee on Foreign Affairs 14 House Committee on Homeland Security 15 House Committee on the Judiciary 16 House Committee on Natural Resources 17 House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform 18 House Committee on Rules 19 House Committee on Science, Space and Technology 20 House Committee on Small Business 21 House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure 22 House Committee on Veterans' Affairs 23 House Committee on Ways and Means 24 House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence 25 © 2012 K&L Gates LLP Page 1 Senate Key Code 26 Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry 27 Senate Committee on Appropriations 28 Senate Committee on Armed Services 29 Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs 30 Senate Committee on the Budget 31 Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation 32 Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources 33 Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works 34 Senate Committee on Finance 35 Senate Committee on Foreign -

District 16 District 142 Brandon Creighton Harold Dutton Room EXT E1.412 Room CAP 3N.5 P.O

Elected Officials in District E Texas House District 16 District 142 Brandon Creighton Harold Dutton Room EXT E1.412 Room CAP 3N.5 P.O. Box 2910 P.O. Box 2910 Austin, TX 78768 Austin, TX 78768 (512) 463-0726 (512) 463-0510 (512) 463-8428 Fax (512) 463-8333 Fax 326 ½ N. Main St. 8799 N. Loop East Suite 110 Suite 305 Conroe, TX 77301 Houston, TX 77029 (936) 539-0028 (713) 692-9192 (936) 539-0068 Fax (713) 692-6791 Fax District 127 District 143 Joe Crab Ana Hernandez Room 1W.5, Capitol Building Room E1.220, Capitol Extension Austin, TX 78701 Austin, TX 78701 (512) 463-0520 (512) 463-0614 (512) 463-5896 Fax 1233 Mercury Drive 1110 Kingwood Drive, #200 Houston, TX 77029 Kingwood, TX 77339 (713) 675-8596 (281) 359-1270 (713) 675-8599 Fax (281) 359-1272 Fax District 144 District 129 Ken Legler John Davis Room E2.304, Capitol Extension Room 4S.4, Capitol Building Austin, TX 78701 Austin, TX 78701 (512) 463-0460 (512) 463-0734 (512) 463-0763 Fax (512) 479-6955 Fax 1109 Fairmont Parkway 1350 NASA Pkwy, #212 Pasadena, 77504 Houston, TX 77058 (281) 487-8818 (281) 333-1350 (713) 944-1084 (281) 335-9101 Fax District 145 District 141 Carol Alvarado Senfronia Thompson Room EXT E2.820 Room CAP 3S.06 P.O. Box 2910 P.O. Box 2910 Austin, TX 78768 Austin, TX 78768 (512) 463-0732 (512) 463-0720 (512) 463-4781 Fax (512) 463-6306 Fax 8145 Park Place, Suite 100 10527 Homestead Road Houston, TX 77017 Houston, TX (713) 633-3390 (713) 649-6563 (713) 649-6454 Fax Elected Officials in District E Texas Senate District 147 2205 Clinton Dr. -

Values Voter Handbook H H H H

2H 0 H1H2 VALUES VOTER HANDBOOK H H H H iVOTE VALUES.ORG 100 DAYS TO IMPACT THE NATION INSIDE: – PRESIDENTIAL VOTER GUIDE – Which presidential candidate represents your Values? – CONGRESSIONAL SCORECARD – Do your senators and representative deserve your vote? ® The stakes in the 2012 election could not be higher. With policies emanating from Washington DC that challenge our historic understanding of religious liberty and force millions of Americans to violate their religious beliefs—the implications of this election are hard to overstate. So which path will Americans choose, and more importantly, how should Christians be involved? 1. Be Informed At Family Research Council we believe it is incumbent upon Americans of religious conviction to be informed and engaged citizens. Voting our values is one important and tangible way that we bear witness to our faith and serve our fellow man. To help you better understand the policies affecting your faith, family and freedom, and the many candidates who stand poised to play a role in shaping those policies, we are pleased to present our 2012 Values Voter Handbook. We designed this resource to provide you with all the information you need to cast an informed, values based vote this election cycle for those candidates running for federal office. This booklet combines both our Presidential Voter Guide and our Congressional Vote Scorecard with documentation to show where the major candidates stand on the issues and how your elected representatives voted in the 1st session of the 112th Congress. 2. Vote Your Values Up and down the ticket, men and women are seeking your vote for local, state and federal offices.But do they merit your support? Before you prayerfully cast your vote, join with Americans from across the nation and declare that you will be a Values Champion this fall, and only support those candidates who share and advocate for your cherished values: Protect Life ~ Honor Marriage ~ Respect Religious Liberty Make the Values Champion pledge by going online at iVoteValues.org. -

Letter to Congressional Black Caucus

December 4, 2020 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Kevin McCarthy Speaker of the House Minority Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives H-232, U.S. Capitol H-204, U.S. Capitol Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader McCarthy: As members of the Congressional Black Caucus, we want to thank you for your efforts to ensure access to health care for patients and to ensure that physicians and specialists around the country have been able to continue operations during this pandemic. However, we are becoming increasingly concerned about looming cuts facing many specialists, which are expected to go into effect beginning on January 1, 2021. On December 1, 2020, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) published the final rule for the CY2021 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, which increased rates for the office-based evaluation and management (E/M) code set in CY2021. Due to the requirement for budget neutrality, this will result in sizable cuts for over thirty healthcare specialties. While we are supportive of the increases for the office-based E/M code set, the resulting cuts are ill-conceived in the middle of a pandemic. Even without these cuts, too many practices are struggling, even as patients need access to health care now more than ever. We are aware of solutions to either waive budget neutrality requirements (H.R. 8505) or to hold specialists harmless (H.R. 8702). While not perfect, either of these solutions would give healthcare specialists the financial security they need to weather the COVID-19 pandemic. -

April 29, 2020 the Honorable Greg Abbott Governor of Texas P.O. Box

April 29, 2020 The Honorable Greg Abbott Governor of Texas P.O. Box 12428 Austin, TX 78711 Delivered via Email Dear Governor Abbott: Long-term care facilities like nursing homes, state supported living centers, and group homes are now the epicenters of the COVID-19 pandemic. While media outlets have rightly focused on the deaths in nursing homes across the country, people with disabilities and older adults face increased risks in all institutional and congregate settings. Like nursing homes, there have been similar outbreaks and deaths in our state supported living centers, state hospitals, and group homes. Our state government can and must do more to protect our most vulnerable Texans. That is why we respectfully request the following critical measures to defend our elderly Texans, Texans with disabilities, and the Texans on the frontline serving these communities. • Immediate additional funding through an emergency Texas Medicaid rate increase for long-term and intermediate care facilities to help cover increased costs for direct-care staff wages and personal protective equipment (PPE); • Greater transparency in the reporting of COVID-19 deaths and cases in nursing home facilities, state supported living centers, state hospitals, and group homes; • Mandatory available COVID-19 testing for every employee and resident of a nursing home facility, state supported living centers, state hospitals, or group home in Texas. Thank you for your consideration of our request, and ensuring Texas protects our most vulnerable. Please do not hesitate -

Researching Alzheimer's Disease Among Underserved Texans

Researching Alzheimer’s Disease among Underserved Texans Sid E. O’Bryant, PhD Director, Rural Health Research F. Marie Hall Institute for Rural & Community Health Assistant Professor Department of Neurology Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Lubbock, Texas 1 Demographics of Texas • Texas is rich in ethnic, cultural, and geographic diversity • As of 2008 – Hispanic/Latino = 37% of TX population – African American = 12% of TX population • Rural = 17% of population 2 Why is it important to study Alzheimer’s Disease among Texans of Hispanic Origin? • As of 2008, Texas was home to 8.9 million Hispanics – 48% of all Hispanics in U.S. reside in either Texas or California – Nearly one quarter of Texas population is Mexican American – 97% of Starr County is Hispanic – All top 10 U.S. counties for highest Hispanic populations are in Texas • The Texas Hispanic population is younger than the non-Hispanic population – Hispanics are the fastest aging population in Texas – Therefore, the numbers of Hispanic Texans developing Alzheimer’s disease will continue to grow rapidly • There are cultural barriers that need to be addressed – Term “dementia” – Obtaining informant reports 3 Why is it important to study Alzheimer’s Disease among Texans of Hispanic Origin? • Hispanic elders present for initial examination to dementia specialty clinics later during the course of Alzheimer’s disease • There is evidence suggesting that Hispanics may develop the disease at a younger age • It is possible that different biological mechanisms drive Alzheimer’s disease between ethnic/racial groups – In Hispanics, diabetes may be stronger driving factor • There is very little research on Alzheimer’s disease among Hispanic populations (or Mexican Americans), despite the fact that this is the largest ethnic minority group in the U.S. -

IDEOLOGY and PARTISANSHIP in the 87Th (2021) REGULAR SESSION of the TEXAS LEGISLATURE

IDEOLOGY AND PARTISANSHIP IN THE 87th (2021) REGULAR SESSION OF THE TEXAS LEGISLATURE Mark P. Jones, Ph.D. Fellow in Political Science, Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy July 2021 © 2021 Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy This material may be quoted or reproduced without prior permission, provided appropriate credit is given to the author and the Baker Institute for Public Policy. Wherever feasible, papers are reviewed by outside experts before they are released. However, the research and views expressed in this paper are those of the individual researcher(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Baker Institute. Mark P. Jones, Ph.D. “Ideology and Partisanship in the 87th (2021) Regular Session of the Texas Legislature” https://doi.org/10.25613/HP57-BF70 Ideology and Partisanship in the 87th (2021) Regular Session of the Texas Legislature Executive Summary This report utilizes roll call vote data to improve our understanding of the ideological and partisan dynamics of the Texas Legislature’s 87th regular session. The first section examines the location of the members of the Texas Senate and of the Texas House on the liberal-conservative dimension along which legislative politics takes place in Austin. In both chambers, every Republican is more conservative than every Democrat and every Democrat is more liberal than every Republican. There does, however, exist substantial ideological diversity within the respective Democratic and Republican delegations in each chamber. The second section explores the extent to which each senator and each representative was on the winning side of the non-lopsided final passage votes (FPVs) on which they voted. -

105Th Congress 293

TEXAS 105th Congress 293 TWENTY-SEVENTH DISTRICT SOLOMON P. ORTIZ, Democrat, of Corpus Christi, TX; born in Robstown, TX, on June 3, 1938; attended Robstown High School; attended Del Mar College, Corpus Christi; officers certificate, Institute of Applied Science, Chicago, IL, 1962; officers certificate, National Sheriffs Training Institute, Los Angeles, CA, 1977; served in U.S. Army, Sp4c. 1960±62; insurance agent; Nueces County constable, 1965±68; Nueces County commissioner, 1969±76; Nueces County sheriff, 1977±82; member: Congressional Hispanic Caucus (chairman, 102nd Congress); Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute (chairman of the board, 102nd Congress); Army Cau- cus; Depot Caucus; Sheriffs' Association of Texas, National Sheriffs' Association, Corpus Christi Rotary Club, American Red Cross, United Way; honors: Who's Who among Hispanic Americans; Man of the Year, International Order of Foresters (1981); Conservation Legislator of the Year for the Sportsman Clubs of Texas (1986), Boss of the Year by the American Busi- nesswomen Association (1980); National Government Hispanic Business Advocate, U.S. His- panic Chamber of Commerce (1992); Leadership Award, Latin American Management Associa- tion (1991); National Security Leadership Award, American Security Council (1992); Tree of Life Award, Jewish National Fund (1987); two children: Yvette and Solomon, Jr.; elected on November 2, 1982 to the 98th Congress; reelected to each succeeding Congress. Office Listings 2136 Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515±4327 ....................... 225±7742 Administrative Assistant.ÐFlorencio H. Rendon. FAX: 226±1134 Executive Assistant/Scheduling.ÐJoe Galindo. Deputy Chief of Staff.ÐVickie Plunkett. Press Secretary.ÐCathy Travis. Suite 510, 3649 Leopard, Corpus Christi, TX 78408 ................................................. (512) 883±5868 Suite 200, 3505 Boca Chica Boulevard, Brownsville, TX 78521 ............................. -

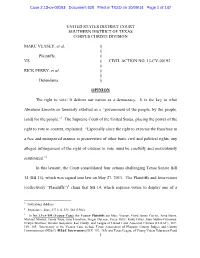

Case 2:13-Cv-00193 Document 628 Filed in TXSD on 10/09/14 Page 1 of 147

Case 2:13-cv-00193 Document 628 Filed in TXSD on 10/09/14 Page 1 of 147 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS CORPUS CHRISTI DIVISION MARC VEASEY, et al, § § Plaintiffs, § VS. § CIVIL ACTION NO. 13-CV-00193 § RICK PERRY, et al, § § Defendants. § OPINION The right to vote: It defines our nation as a democracy. It is the key to what Abraham Lincoln so famously extolled as a “government of the people, by the people, [and] for the people.”1 The Supreme Court of the United States, placing the power of the right to vote in context, explained: “Especially since the right to exercise the franchise in a free and unimpaired manner is preservative of other basic civil and political rights, any alleged infringement of the right of citizens to vote must be carefully and meticulously scrutinized.”2 In this lawsuit, the Court consolidated four actions challenging Texas Senate Bill 14 (SB 14), which was signed into law on May 27, 2011. The Plaintiffs and Intervenors (collectively “Plaintiffs”)3 claim that SB 14, which requires voters to display one of a 1 Gettysburg Address. 2 Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 562 (1964). 3 In No. 13-cv-193 (Veasey Case), the Veasey Plaintiffs are Marc Veasey, Floyd James Carrier, Anna Burns, Michael Montez, Penny Pope, Jane Hamilton, Sergio DeLeon, Oscar Ortiz, Koby Ozias, John Mellor-Crummey, Evelyn Brickner, Gordon Benjamin, Ken Gandy, and League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC). D.E. 109, 385. Intervenors in the Veasey Case include Texas Association of Hispanic County Judges and County Commissioners (HJ&C) (HJ&C Intervenors) (D.E.