Select Committee on Judicial Interpretation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Policy Report Texas Fact Book 2010

Texas Fact Book 2010 Legislative Budget Board LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD EIGHTY-FIRST TEXAS LEGISLATURE 2009 – 2010 DAVID DEWHURST, JOINT CHAIR Lieutenant Governor JOE STRAUS, JOINT CHAIR Representative District 121, San Antonio Speaker of the House of Representatives STEVE OGDEN Senatorial District 5, Bryan Chair, Senate Committee on Finance ROBERT DUNCAN Senatorial District 28, Lubbock JOHN WHITMIRE Senatorial District 15, Houston JUDITH ZAFFIRINI Senatorial District 21, Laredo JIM PITTS Representative District 10, Waxahachie Chair, House Committee on Appropriations RENE OLIVEIRA Representative District 37, Brownsville Chair, House Committee on Ways and Means DAN BRANCH Representative District 108, Dallas SYLVESTER TURNER Representative District 139, Houston JOHN O’Brien, Director COVER PHOTO COURTESY OF HOUSE PHOTOGRAPHY CONTENTS STATE GOVERNMENT STATEWIDE ELECTED OFFICIALS . 1 MEMBERS OF THE EIGHTY-FIRST TEXAS LEGISLATURE . 3 The Senate . 3 The House of Representatives . 4 SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES . 8 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEES . 10 BASIC STEPS IN THE TEXAS LEGISLATIVE PROCESS . 14 TEXAS AT A GLANCE GOVERNORS OF TEXAS . 15 HOW TEXAS RANKS Agriculture . 17 Crime and Law Enforcement . 17 Defense . 18 Economy . 18 Education . 18 Employment and Labor . 19 Environment and Energy . 19 Federal Government Finance . 20 Geography . 20 Health . 20 Housing . 21 Population . 21 Science and Technology . 22 Social Welfare . 22 State and Local Government Finance . 22 Transportation . 23 Border Facts . 24 STATE HOLIDAYS, 2010 . 25 STATE SYMBOLS . 25 POPULATION Texas Population Compared with the U .s . 26 Texas and the U .s . Annual Population Growth Rates . 27 Resident Population, 15 Most Populous States . 28 Percentage Change in Population, 15 Most Populous States . 28 Texas Resident Population, by Age Group . -

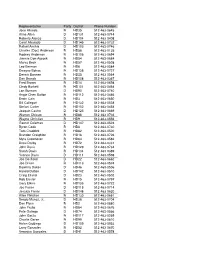

82Nd Leg Members

Representative Party District Phone Number Jose Aliseda R HD35 512-463-0645 Alma Allen D HD131 512-463-0744 Roberto Alonzo D HD104 512-463-0408 Carol Alvarado D HD145 512-463-0732 Rafael Anchia D HD103 512-463-0746 Charles (Doc) Anderson R HD56 512-463-0135 Rodney Anderson R HD106 512-463-0694 Jimmie Don Aycock R HD54 512-463-0684 Marva Beck R HD57 512-463-0508 Leo Berman R HD6 512-463-0584 Dwayne Bohac R HD138 512-463-0727 Dennis Bonnen R HD25 512-463-0564 Dan Branch R HD108 512-463-0367 Fred Brown R HD14 512-463-0698 Cindy Burkett R HD101 512-463-0464 Lon Burnam D HD90 512-463-0740 Angie Chen Button R HD112 512-463-0486 Erwin Cain R HD3 512-463-0650 Bill Callegari R HD132 512-463-0528 Stefani Carter R HD102 512-463-0454 Joaquin Castro D HD125 512-463-0669 Warren Chisum R HD88 512-463-0736 Wayne Christian R HD9 512-463-0556 Garnet Coleman D HD147 512-463-0524 Byron Cook R HD8 512-463-0730 Tom Craddick R HD82 512-463-0500 Brandon Creighton R HD16 512-463-0726 Myra Crownover R HD64 512-463-0582 Drew Darby R HD72 512-463-0331 John Davis R HD129 512-463-0734 Sarah Davis R HD134 512-463-0389 Yvonne Davis D HD111 512-463-0598 Joe Deshotel D HD22 512-463-0662 Joe Driver R HD113 512-463-0574 Dawnna Dukes D HD46 512-463-0506 Harold Dutton D HD142 512-463-0510 Craig Eiland D HD23 512-463-0502 Rob Eissler R HD15 512-463-0797 Gary Elkins R HD135 512-463-0722 Joe Farias D HD118 512-463-0714 Jessica Farrar D HD148 512-463-0620 Allen Fletcher R HD130 512-463-0661 Sergio Munoz, Jr. -

Interim Report to the 82Nd Texas Legislature

InterIm report to the 82nd texas LegisLature House Committee on State affairS December 2010 ______________________________________________________________________________ HOUSE COMMITTEE ON STATE AFFAIRS TEXAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES INTERIM REPORT 2010 BURT R. SOLOMONS CHAIRMAN LESLEY FRENCH COMMITTEE CLERK/GENERAL COUNSEL ROBERT ORR DEPUTY COMMITTEE CLERK/POLICY ANALYST ALFRED BINGHAM LEGAL INTERN ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ COMMITTEE ON STATE AFFAIRS TEXAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES P.O. BOX 2910 • AUSTIN, TEXAS 78768-2910 CAPITOL EXTENSION E2.108 • (512) 463-0814 September 27th, 2010 The Honorable Joe Straus Speaker, Texas House of Representatives Texas State Capitol, Rm. 2W.13 Austin, Texas 78701 Dear Mr. Speaker and Fellow Members: The Committee on State Affairs of the Eighty-First Legislature hereby submits its interim report for consideration by the Eighty-Second Legislature. Respectfully submitted, _______________________ Burt Solomons, Chair _______________________ _______________________ Rep. José Menéndez, Vice-Chair Rep. Byron Cook _______________________ _______________________ Rep. Tom Craddick Rep. David Farabee _______________________ _______________________ Rep. Pete Gallego Rep. Charlie Geren ______________________ _______________________ Rep. Patricia Harless Rep. Harvey Hilderbran ______________________ _______________________ Rep. Delwin Jones Rep. Eddie Lucio III _______________________ -

Policy Report Texas Fact Book 2008

Texas Fact Book 2 0 0 8 L e g i s l a t i v e B u d g e t B o a r d LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD EIGHTIETH TEXAS LEGISLATURE 2007 – 2008 DAVID DEWHURST, JOINT CHAIR Lieutenant Governor TOM CRADDICK, JOINT CHAIR Representative District 82, Midland Speaker of the House of Representatives STEVE OGDEN Senatorial District 5, Bryan Chair, Senate Committee on Finance ROBERT DUNCAN Senatorial District 28, Lubbock JOHN WHITMIRE Senatorial District 15, Houston JUDITH ZAFFIRINI Senatorial District 21, Laredo WARREN CHISUM Representative District 88, Pampa Chair, House Committee on Appropriations JAMES KEFFER Representative District 60, Eastland Chair, House Committee on Ways and Means FRED HILL Representative District 112, Richardson SYLVESTER TURNER Representative District 139, Houston JOHN O’Brien, Director COVER PHOTO COURTESY OF SENATE MEDIA CONTENTS STATE GOVERNMENT STATEWIDE ELECTED OFFICIALS . 1 MEMBERS OF THE EIGHTIETH TEXAS LEGISLATURE . 3 The Senate . 3 The House of Representatives . 4 SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES . 8 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEES . 10 BASIC STEPS IN THE TEXAS LEGISLATIVE PROCESS . 14 TEXAS AT A GLANCE GOVERNORS OF TEXAS . 15 HOW TEXAS RANKS Agriculture . 17 Crime and Law Enforcement . 17 Defense . 18 Economy . 18 Education . 18 Employment and Labor . 19 Environment and Energy . 19 Federal Government Finance . 20 Geography . 20 Health . 20 Housing . 21 Population . 21 Social Welfare . 22 State and Local Government Finance . 22 Technology . 23 Transportation . 23 Border Facts . 24 STATE HOLIDAYS, 2008 . 25 STATE SYMBOLS . 25 POPULATION Texas Population Compared with the U .s . 26 Texas and the U .s . Annual Population Growth Rates . 27 Resident Population, 15 Most Populous States . -

Appendix a – List of Recipients

Preliminary Engineering / Environmental Impact Statement Northwest Corridor LRT Line to Irving and DFW Airport Appendix A – List of Recipients FEDERAL AGENCIES Michael A. McMullen, Stakeholder Manager, Transportation Security Administration Ralston Cox, Administration Director, Advisory Council on Historic Preservation Donald R. Sutherland, NEPA Coordinator, Bureau of Indian Affairs Ann B. Aldrich, Group Manager, Planning, Assessment, and Community Support, Bureau of Land Management Dirk Kempthorne, Secretary of Interior, Department of the Interior Willie Taylor, Director, Office of Environmental Policy and Compliance, Department of the Interior William E. Peterson, Regional Director, Federal Emergency Management Agency Region 6 Sal Deocampo, District Engineer, Federal Highway Administration, Texas Division David Visney, Regional Manager, Federal Railroad Administration Leighton W. Waters, Acting Regional Administrator, General Service Administration, Region 7 Don Babers, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Dallas Office Colonel John R. Minahan, Commander, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Fort Worth District Wayne Lea, Chief, Regulatory Branch, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Fort Worth District Rear Admiral Robert Duncan, District Commander, U.S. Coast Guard, 8th District Richard Greene, Administrator, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 6 Carl Edlund, Division Director, Multimedia Planning and Permitting Division, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 6 Michael Jansky, EIS Review Coordinator, Compliance Assurance -

Legislative Staff

Page 2 House Research Organization Table of Contents House of Representatives .................... 3 House Committees ............................. 13 Senate ................................................ 16 Senate Committees ............................ 19 Other State Numbers ......................... 21 Page 3 House Research Organization House of Representatives ALLEN, Alma A. E1.216 BERMAN, Leo E2. 908 Phone: 463-0744 Phone: 463-0584 Fax: 463-5896 Fax: 463-3217 Chief of staff .................................Annabell Lopez Chief of staff .................................Gloria Rogers Legislative aides ...........................Marye Dean Legislative aide ............................Patrick Dudley Teresa LeNoir Legislative interns ........................Keith Alaniz Claudia Madrigal ALLEN, Ray GN.7 Kirby McLain Phone: 463-0694 Fax: 463-1130 BLAKE, Roy Jr. E2. 404 Legislative aide ............................Lauren Thomas Phone: 463-0556 Administrative aide .......................Theresa Huchingson Fax: 463-5896 Policy director ...............................Marsha McLane Legislative director .......................Michele Moore Administrative director ..................Josh Robinson ALONZO, Roberto R. E2.910 Legislative aide ............................Pam Dixon Phone: 463-0408 Fax: 463-1817 BOHAC, Dwayne E2.414 Chief of staff .................................Jesse R. Bernal Phone: 463-0727 Administrative aide .......................Denyce E. Deadrick Fax: 463-0681 Legislative aide ............................Luis Martinez Chief -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 02-102 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- JOHN GEDDES LAWRENCE AND TYRONE GARNER, Petitioners, v. STATE OF TEXAS, Respondent. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Writ Of Certiorari To The Court Of Appeals Of Texas, Fourteenth District --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE TEXAS LEGISLATORS, REPRESENTATIVE WARREN CHISUM, ET AL., IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- SCOTT ROBERTS KELLY SHACKELFORD 1206 Oakwood Trail Counsel of Record Southlake, Texas 76092 HIRAM S. SASSER III (817) 424-3923 LIBERTY LEGAL INSTITUTE 903 18th Street, Suite 230 Plano, Texas 75074 (972) 423-3131 ================================================================ COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. (800) 225-6964 OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831 Amici are: Texas Legislators: Representative Warren Chisum; Representative Will Hartnet, Chair, House Committee on Judicial Affairs; Representative Diane Delisi; Representative Mary Denny; Representative Rob Eissler; Representative Mike Flynn; Representative Toby Goodman; Representative Mike Hamilton; Representative Anna Mowery; Representative Beverly Wooley; Representative Geanie Morrison; Representative Phil King; Representative Carl Isett; Representative Charlie Howard; Representative Leo Berman; Representative Dwayne Bohac; Representative -

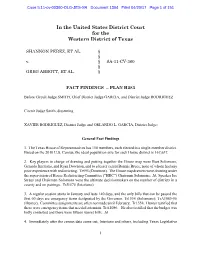

Fact Findings on Plan H283

Case 5:11-cv-00360-OLG-JES-XR Document 1364 Filed 04/20/17 Page 1 of 151 In the United States District Court for the Western District of Texas SHANNON PEREZ, ET AL. § § v. § SA-11-CV-360 § GREG ABBOTT, ET AL. § FACT FINDINGS – PLAN H283 Before Circuit Judge SMITH, Chief District Judge GARCIA, and District Judge RODRIGUEZ Circuit Judge Smith, dissenting XAVIER RODRIGUEZ, District Judge and ORLANDO L. GARCIA, District Judge: General Fact Findings 1. The Texas House of Representatives has 150 members, each elected in a single-member district. Based on the 2010 U.S. Census, the ideal population size for each House district is 167,637. 2. Key players in charge of drawing and putting together the House map were Burt Solomons, Gerardo Interiano, and Ryan Downton, and to a lesser extent Bonnie Bruce, none of whom had any prior experience with redistricting. Tr995 (Downton). The House mapdrawers were drawing under the supervision of House Redistricting Committee (“HRC”) Chairman Solomons. Id. Speaker Joe Straus and Chairman Solomons were the ultimate decisionmakers on the number of districts in a county and on pairings. TrJ1575 (Interiano). 3. A regular session starts in January and lasts 140 days, and the only bills that can be passed the first 60 days are emergency items designated by the Governor. Tr1558 (Solomons); TrA1085-86 (Hunter). Committee assignments are often not made until February. Tr1558. Hunter testified that there were emergency items that needed attention. TrA1086. He also testified that the budget was hotly contested and there were fifteen sunset bills. Id. 4. -

Salsa2journal 1..20

HOUSE JOURNAL EIGHTY-FIRST LEGISLATURE, REGULAR SESSION PROCEEDINGS FIRST DAY Ð TUESDAY, JANUARY 13, 2009 In accordance with the laws and Constitution of the State of Texas, the members-elect of the house of representatives assembled this day in the hall of the house of representatives in the city of Austin at 12 noon. The Honorable Hope Andrade, secretary of state of the State of Texas, called the House of Representatives of the Eighty-First Legislature of the State of Texas to order. The invocation was offered by Archbishop Daniel Nicholas Cardinal DiNardo of Galveston-Houston, as follows: Almighty and compassionate Lord, you have revealed your glory to all nations and have care for all. We humbly thank you for this land, our state, a land rich in resources but above all rich in its many people. May we be a people mindful of your love and kindness. Save us from violence, discord and confusion, from pride and arrogance, and from every evil way. God of power and might, wisdom and justice, through you authority is rightly administered, laws are enacted, and judgement is decreed. Let the light of your divine wisdom direct the deliberations of this legislature and shine forth in all its proceedings and laws framed for our rule and governance. May this house of representatives seek to preserve the common good and continue to bring us the blessings of liberty and equality. Assist with your spirit of counsel and fortitude the speaker and all representatives, that their administration be conducted in right judgment and be eminently useful to the citizens of this state. -

Liberals and Conservatives in the 2011 Texas House of Representatives

JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY RICE UNIVERSITY LIBERALS AND CONSERVATIVES IN THE 2011 TEXAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES BY MARK P. JONES, PH.D. FELLOW IN POLITICAL SCIENCE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY RICE UNIVERSITY SEPTEMBER 22, 2011 The 2011 Texas House of Representatives THESE PAPERS WERE WRITTEN BY A RESEARCHER (OR RESEARCHERS) WHO PARTICIPATED IN A BAKER INSTITUTE RESEARCH PROJECT. WHEREVER FEASIBLE, THESE PAPERS ARE REVIEWED BY OUTSIDE EXPERTS BEFORE THEY ARE RELEASED. HOWEVER, THE RESEARCH AND VIEWS EXPRESSED IN THESE PAPERS ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL RESEARCHER(S), AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT THE VIEWS OF THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY. © 2011 BY THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY OF RICE UNIVERSITY THIS MATERIAL MAY BE QUOTED OR REPRODUCED WITHOUT PRIOR PERMISSION, PROVIDED APPROPRIATE CREDIT IS GIVEN TO THE AUTHOR AND THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY. 2 The 2011 Texas House of Representatives I. Introduction Political scientists have long used roll call votes cast by members of the U.S. Congress to plot the legislators on the liberal-conservative dimension along which most legislative politics in our nation’s capital (as well as in Austin) now takes place.1 Here, drawing on the data provided by roll call votes held during the combined 2011 regular and first special legislative sessions (January-June), I provide similar information for the members of the Texas House of Representatives. These data provide a window from which to view only one facet of a representative’s activities in Austin, and should thus be considered as one of many tools utilized by citizens to evaluate their elected officials. -

The November 2008 Texas Ballot

The November 2008 Texas Ballot This post-primary look at the ballots includes Republicans, Democrats, and Libertarians (who will choose their candidates at their state convention). Incumbents names are in bold. Here's how the Texas Weekly Index (TWI) works: It's the average difference between statewide Republicans and statewide Democrats in contested elections in 2004 and 2006, by district. If it's red, or a negative number, Republicans did better in that district; if it's blue or a positive number, Democrats did better. It's not meant to predict results, but to give you a quick look at recent political history in each district. Copyright 2008 Texas Weekly Texas Statewide Races - 2008 Office/District TWI Republicans Democrats Libertarians Scott Jameson, Plano; Jon U.S. Senate -16.9 John Cornyn, San Antonio Rick Noriega, Houston Roland, Austin; Yvonne Adams Schick, Spicewood Railroad -16.9 Michael Williams, Austin Mark Thompson, Hamilton David Floyd, Austin Commission Texas Supreme Court, Chief -16.9 Wallace Jefferson, Austin Jim Jordan, Dallas Tom Oxford, Beaumont Justice Texas Supreme -16.9 Dale Wainwright, Austin Sam Houston, Houston David Smith, Henderson Court, Place 7 Texas Supreme -16.9 Phil Johnson, Austin Linda Yañez, Edinburg Drew Shirley, Round Rock Court, Place 8 Texas Court of Criminal -16.9 Tom Price, Richardson Susan Strawn, Houston Matthew Eilers, Universal City Appeals, Place 3 Texas Court of Criminal -16.9 Paul Womack, Georgetown J.R. Molina, Fort Worth Dave Howard, Round Rock Appeals, Place 4 Texas Court of William Bryan -

82Nd Legislative Session Staff Report Session Overview • Session Began January 11, 2011 and Concluded After 140 Days on May 30,2011

82nd Legislative Session Staff Report Session Overview • Session began January 11, 2011 and concluded after 140 days on May 30,2011. • Staff Representatives: Bruce Glasscock, Frank Turner, & Mark Israelson; ▫ Assisted by Sherry Jackson. • City Legislative Program Key Issues : ▫ Revenue ▫ Home rule authority ▫ Unfunded mandates ▫ Economic development ▫ Transportation ▫ Civil Service ▫ Water • City Actions: ▫ Take positions on bills: for, against, neutral, no-impact or follow (vehicles); ▫ Provide Testimony, letters, e-mail or phone calls; ▫ Work with key partners including Texas Municipal League (TML) and legislative delegation. Thanks to the Plano Delegation Senate House of Representatives Representative Burt Representative Van Representative Jerry Solomons Senator Florence Taylor Madden Shapiro House District 65 House District 66 House District 67 Senate District 8 Representative Ken Representative Jody Paxton Laubenberg House District 70 House District 89 3/01/11 3 82nd Legislative Session Bills • In the 2011 session, lawmakers filed fewer bills than in recent previous Total sessions. Total Bills Bills City-Related City-Related Year Introduced Passed Bills Introduced Bills Passed • 6,303 bills and proposed 1993 4,560 1,089 800+ 140+ constitutional amendments were filed. 1995 5,147 1,101 800+ 140+ • Compared to the 7,609 bills in 2009, 1997 5,741 1,502 1,100+ 130+ this was a decrease of more than 20 %. 1999 5,908 1,638 1,230+ 130+ • TML tracked almost 1,500 bills that 2001 5,712 1,621 1,200+ 150+ could have affected city authority. 2003 5,754 1,403 1,200+ 110+ • November 8 – March 11: 50 bills per 2005 5,369 1,397 1,200+ 105+ calendar day.