Dance Topics I: Music and Dance in the Ancien Régime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

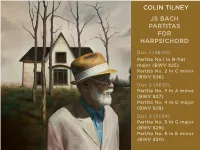

Js Bach Partitas for Harpsichord Colin Tilney

COLIN TILNEY JS BACH PARTITAS FOR HARPSICHORD Disc 1 (48:34) Partita No.1 in B-flat major (BWV 825) Partita No. 2 in C minor (BWV 826) Disc 2 (56:51) Partita No. 3 in A minor (BWV 827) Partita No. 4 in D major (BWV 828) Disc 3 (51:54) Partita No. 5 in G major (BWV 829) Partita No. 6 in E minor (BWV 830) COLIN TILNEY js bach partitas for harpsichord Disc 1 (48:34) Disc 2 (56:51) Disc 3 (51:54) Partita No.1 in B-flat major (BWV 825) Partita No. 3 in A minor (BWV 827) Partita No. 5 in G major (BWV 829) 1. 1. Præludium 2:24 Fantasia 3:17 1. Præambulum 3:14 2. 2. Allemande 4:59 Allemande 3:19 2. Allemande 2:55 3. 3. Corrente 4:09 Corrente 2:12 3. Corrente 2:49 4. Sarabande 6:16 4. Sarabande 3:54 4. Sarabande 4:11 5. Menuets 1 & 2 3:30 5. Burlesca 2:59 5. Tempo di Minuetta 2:30 6. Gigue 3:48 6. Scherzo 1:50 6. Passepied 2:24 7. Gigue 5:34 7. Gigue 3:24 Partita No. 2 in C minor (BWV 826) Partita No. 4 in D major (BWV 828) 7. Sinfonia 5:50 Partita No. 6 in E minor (BWV 830) 8. Ouverture 7:57 8. Allemande 5:32 8. Toccata 8:24 9. Allemande 6:12 9. Courante 3:34 9. Allemanda 4:33 10. Courante 5:16 10. Sarabande 3:34 10. Corrente 3:24 11. -

Baroque and Classical Style in Selected Organ Works of The

BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL STYLE IN SELECTED ORGAN WORKS OF THE BACHSCHULE by DEAN B. McINTYRE, B.A., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee Accepted Dearri of the Graduate jSchool December, 1998 © Copyright 1998 Dean B. Mclntyre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for the general guidance and specific suggestions offered by members of my dissertation advisory committee: Dr. Paul Cutter and Dr. Thomas Hughes (Music), Dr. John Stinespring (Art), and Dr. Daniel Nathan (Philosophy). Each offered assistance and insight from his own specific area as well as the general field of Fine Arts. I offer special thanks and appreciation to my committee chairperson Dr. Wayne Hobbs (Music), whose oversight and direction were invaluable. I must also acknowledge those individuals and publishers who have granted permission to include copyrighted musical materials in whole or in part: Concordia Publishing House, Lorenz Corporation, C. F. Peters Corporation, Oliver Ditson/Theodore Presser Company, Oxford University Press, Breitkopf & Hartel, and Dr. David Mulbury of the University of Cincinnati. A final offering of thanks goes to my wife, Karen, and our daughter, Noelle. Their unfailing patience and understanding were equalled by their continual spirit of encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT ix LIST OF TABLES xi LIST OF FIGURES xii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES xiii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xvi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 11. BAROQUE STYLE 12 Greneral Style Characteristics of the Late Baroque 13 Melody 15 Harmony 15 Rhythm 16 Form 17 Texture 18 Dynamics 19 J. -

Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano Amy Jun Ming Chin Minnesota State University - Mankato

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects 2012 Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano Amy Jun Ming Chin Minnesota State University - Mankato Follow this and additional works at: http://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Chin, Amy Jun Ming, "Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano" (2012). Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects. Paper 195. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano By Amy J. Chin Program Notes Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music In Piano Performance Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota April 2012 Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano Amy Jun Ming Chin This program notes has been examined and approved by the following members of the program notes committee. Dr. David Viscoli, Advisor Dr.Linda B. Duckett Dr. Karen Boubel Preface The purpose of this paper is to offer a biographical background of the composers, and historical and theoretical analysis of the works performed in my Master’s recital. This will assist the listener to better understand the music performed. Acknowledgements I would like to thank members of my examining committee, Dr. -

Lunchtime Concert Slava Grigoryan Guitar Sharon Grigoryan Cello

Sharon Grigoryan has been the cellist with the Australian String Quartet since 2013, and has been invited to be Guest Principal Cellist with the Melbourne, Adelaide and Tasmanian Symphony Orchestras. She is the current Artistic Director of the Barossa, Baroque and Beyond music festival, which recently completed its fifth year. In 2019 Sharon curated a chamber music series, Live at the Quartet Bar, for the Adelaide Festival Centre, and made her debut as a radio presenter on ABC Classic. Regarded as a wizard of the guitar, Slava Grigoryan has forged a prolific reputation as a classical guitar virtuoso. Born in Kazakhstan, he immigrated with his family to Australia in 1981 and began studying the guitar with his violinist father Edward at the age of 6. By the time he was 17 he was signed to the Sony Classical Label. His relationship with Sony Classical, ABC Classic in Australia, ECM in Germany and his own label Which Way Music has led to the release of over 30 solo and collaborative albums – four of which have won ARIA Awards – spanning a vast range of musical genres. Since 2009 Slava has been the Artistic Director of the Adelaide Guitar Festival. Lunchtime Concert Slava Grigoryan guitar Sharon Grigoryan cello Friday 25 September, 1:10pm Throughout, Bach’s contrapuntal genius shows in his ability to project multiple PROGRAM voices and implied harmonies with what is often considered a single-line Jobiniana No. 4 Sergio Assad instrument. Maurice Ravel’s Pièce en forme de Habanera was actually originally written as a Sarabande from Cello Suite No. -

Johann Sebastian Bach and the Fortepiano

Johann Sebastian Bach and the Fortepiano The keyboard music of J.S. Bach (Johann Sebastian Bach, 1685-1750 was mostly intended for the harpsichord. At that time, this instrument had a central position in the musical world, and had reached a state of high perfection. However, because it used a plucked string mechanism, it was not possible to express nuances on the keyboard, by playing loud or soft. The clavichord, on the other hand, another very popular instrument instrument, functioned by striking the strings, thus making different expressive nuances possible. Unfortunately, this instrument had a small range, and an extremely discreet sonority, which makes for a particularly confidential usage: it could hardly be used for public concerts. For that reason, the idea arose of replacing the plucked string system of the harpsichord with another, newly developed mechanism using hammers, which would strike the strings and thus make it possible to play with different dynamics. This was the system developed by Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655-1731), circa 1700 in Florence, Tuscany. Over the years, he developed and perfected his invention to a level of complexity which made his instruments expensive. Simplifications were made soon afterwards, only for the complex designs of Cristofori to reappear later in yet more highly developed pianos. This is a sure sign of his exceptional creativity. The simplified mechanism was introduced by Gottfried Silbermann (1683-1753), a well-known German organ builder, who had shown an interest in Cristofori’s new piano. During the mid-1730s, Silbermann had presented his simplified instrument to J.S. Bach, who was at that time not well pleased; he is said to have complained about the pinched sound in the high notes, and the heavy touch required. -

2020 Bach Festival: Rules, Guidelines, and Agreement

page 1 of 8 2020 Bach Festival: Rules, Guidelines, and Agreement Overview The Seattle International Piano Festival (SIPF) is proud to present for the eleventh annual Bach Festival (online edition) for pianists and stringed instruments of any nationality, featuring works by Johann Sebastian Bach, as well as other Baroque masters. This year’s event will be exclusively online. This competitive event was created to provide performing opportunities for those who wish to share their love of Bach’s revered music and to provide performers with constructive feedback from performing and teaching masters. Participants will receive educational evaluations by performing for adjudicators, and a chance to receive medals and certificates. We are honored to continue the tradition of the annual Bach Festival by its original founder, Jennifer Bowman, and hope to preserve her artistic vision. The festival has always been a wonderful educational and artistic opportunity for pianists and violinists in Washington and Oregon, and our mission is to see that it becomes an anticipated event each year. This festival sets forth narrowly defined age groups and specific genre groups so that participants may be fairly judged, and generously decorated. Those familiar with previous years should note that the only change from last year’s Bach Festival is the inclusion of a Baroque Keyboard Masters performance category. As always, the application form is available electronically: application form Festival Date For 2020, the Bach Festival is conducted on the basis of submitted video links. See video submissions below for details about preparing performances for submission. The deadline for submission is 11:59 pm, Thursday, October 22, 2020. -

Silvius Leopold Weiss the Complete London Manuscript

Silvius Leopold Weiss The Complete London Manuscript Extensive Liner Notes 1 95070 Weiss 2 The London Manuscript unveiled 12 Analysis Conclusions By Michel Cardin ©2005, updated 2014 1. Analysis Conclusions 2. General Context 3. Description of the works 4. Appendix 1 : The late Baroque lute seen trough S.L.Weiss 5. Appendix 2 : Ornamentation and examples 6. Appendix 3 : The slur concept in the late Baroque tablatures The ideas that were developing during my twelve-year artistic and musicological project devoted to the London Manuscript by Silvius Leopold Weiss (1687-1750) brought me to the following conclusions that I could put up on historical and practical verifications. My hope is that these few precisions will bring observers a bit closer to the original intentions. Other musicians and analysts are of course working to find more details of interpretation. My thanks go to the persons who nourished my research by their important discoveries: Douglas Alton Smith, Tim Crawford, Markus Lutz, Frank Legl, Claire Madl, and many others that I cannot mention here. The 12 topics presented below are a synthesis of the most important aspects described in a broader context of tonalities, sources, technical and aesthetical implications in my General context and Description of the works articles. The points here summarised are: 1. Unity and chronology 2. Quality of the works, importance of basses and ornamentation 3. Musical care and editorial negligence 4. Pieces replaced in their context 5. Other composers’ works and dubious works 6. Instrumental polyvalence 7. Works for the non-theorbated lute 8. The added preludes 9. Two categories of minuets and bourrees 10. -

Texte Bach-Gester GB

THE PARTITAS (BWV 825-830) or Clavir-Übung / comprised of preludes, allemandes, courantes, sarabandes, gigues, minuets and other galanteries, to entertain enthusiasts of Johann Sebastian Bach… Opus I, published by the composer in 1731. In the Tradition of a Genre When J.S. Bach undertook composition of the first part of Clavierübung (« keyboard practice »), he had just been appointed in the spring of 1723 to the position of Cantor at Saint Thomas’s and Director Musices in Leipzig. There, he would find himself extremely active: in addition to composing cantatas for Sunday and passions, as well as teaching at Thomasschule, he completed the “French” Suites (circa 1725) which followed on from an impressive collection of “English” Suites for the harpsichord (c. 1723), Suites, Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin, solo cello and solo flute, and the Six “Trios for Keyboard and Violin,” now called “Sonatas for Harpsichord and Violin.” Right in the middle of such intense activity, Bach embarked upon his “great work,” his “Opus 1,” in the sphere of keyboard music and the genre of the French-styled suite, going by the Italian term of partita. As a matter of fact, Bach was preceded by his reputation as a virtuoso and unrivaled improviser on the organ and harpsichord. He had just completed the distinguished educational works of Inventions & Sinfonias comprising two and three parts (1720-23), and the first part of the Well- Tempered Clavier (1722). His activity was focused on all areas of composition and teaching, in keeping with the example set by his illustrious colleagues, Johann Kuhnau, Johann Caspar Ferdinand Fischer, Georg Philipp Telemann, Johann Mattheson, Christoph Graupner and Georg Friedrich Handel, who had issued various publications for an ever-growing, enlightened public of enthusiasts. -

Dance Suite: Comparative Study of Johann Sebastian Bach’S French Overture and Béla Bartók’S Dance Suite

DANCE SUITE: COMPARATIVE STUDY OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH’S FRENCH OVERTURE AND BÉLA BARTÓK’S DANCE SUITE BY JAYOUNG KIM Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music, Indiana University December, 2014! ! ! Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee _____________________________________ Menahem Pressler Chairperson, Research Director _____________________________________ Edmund Battersby _____________________________________ Luba Edlina-Dubinsky ! ii! TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ……………………….………………………………..…….. iii LIST OF EXAMPLES ……………………………...………………………………….. iv INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………………. 1 Chapter I. DANCE, MUSIC AND DANCE SUITE ……………………………………. 3 1. Dance …………………………………………………………………………. 3 2. Music for dance and Dance suite …………………………………….……….. 4 Chapter II. JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH’S FRENCH OVERTURE …………………. 8 1. Background …………………………………………………………………… 8 2. National Influence of the time ………………………………………………... 9 3. Orchestral Suite vs French Overture ............................................................... 11 4. French Overture Analysis …………………………………………………... 14 Chapter III. BÉLA BARTÓK AND DANCE SUITE ………………………………….. 22 1. Background ………………………………………………………………….. 22 2. Dance Suite Analysis on national influence ………………………………… 25 3. Orchestral Dance Suite vs Piano transcription ………………………………. 35 CONCLUSION ………………………………………………………………………… 40 BIBLIOGRAPY ………………………………………………………………………... 42 ! iii! LIST OF EXAMPLES Example 2-1: Johann Sebastian Bach Clavier-bücklein, Volume 1, Preface …….. 11 Example 2-2: J. S. Bach Orchestral Suite, BWV. 1069, Overture, mm. 1-4 …….. 14 Example 2-3: J. S. Bach French Overture, Overture, mm. 1-3 …………………... 15 Example 2-4: Manuscript copy of the French Overture in C minor, mm. 1-3 …… 16 Example 2-5: J. S. Bach French Overture, Courante, mm. 1-3 …………………... 17 Example 2-6: J. S. Bach French Overture, Gavotte I, mm. -

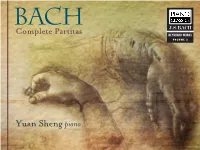

Yuan Sheng Piano JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750)

Bach J.S.BACH Complete Partitas KEYBOARD WORKS VOLUME 2 Yuan Sheng piano JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750) Partita No. 1 in B-Flat Major, Partita No.3 in A Minor, BWV 827 Bach at 40 BWV 825 20. Fantasia 2’08 In 1725 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) was a middle-aged man with 1. Praeludium 1’46 21. Allemande 2’46 an important position since 1723 as Cantor of the legendary choir school of 2. Allemande 3’51 22. Corrente 3’25 St. Thomas Church in Leipzig. He had a formidable reputation as a brilliant 3. Corrente 2’57 23. Sarabande 4’38 keyboardist and an impressive body of compositions, sacred and secular, 4. Sarabande 5’35 24. Burlesca 2’17 for keyboard, chamber ensembles, and orchestra as well as voices. Yet, 5. Menuet I&II 3’09 25. Scherzo 1’10 unlike his most eminent contemporaries with international reputations 6. Giga 2’02 26. Gigue 3’15 (such Handel and Telemann, François Couperin and Rameau, and Corelli, Torelli, and Vivaldi, to name some whose work was known to Bach), Partita No.2 in C Minor, BWV 826 Partita No.5 in G Major, BWV 829 Bach’s music—because it was not published--was essentially unknown 7. Sinfonia 4’16 27. Praeambulum 2’38 beyond the immediate circle of his family, students, and colleagues, or the 8. Allemande 4’37 28. Allemande 4’20 congregations who heard his church music. By 1725, this included not only 9. Courante 2’21 29. Corrente 1’50 most of the keyboard music familiar today—the English and French Suites, 10. -

An Examination of Stylistic Mixture in Four Bassoon Sonatas, 1720–1760

An Examination of Stylistic Mixture in Four Bassoon Sonatas, 1720–1760 A document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2017 by Yi-Chen Chiu B.A., University of Taipei, 2003 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, PhD ABSTRACT The bassoon sonatas written between 1720 and 1760 reflect a turning point both in the instrument’s construction and in compositional style. The newly invented baroque bassoon replaced the older dulcian with greater virtuosic capability. Thanks to these improvements, composers began to view the bassoon as a solo instrument and write music specifically for it. This time period also witnessed a preference for stylistic synthesis, a blending of Italian and French style as well as the old Baroque and the new style galant. This document discusses the significance of the emerging new baroque bassoon. It examines the elements of the mixed styles in the context of formal structure, texture, tonality, harmonic content, and melodic and rhythmic writing. Finally, it evaluates the idiomatic writing that is still challenging for modern bassoonists. Sonatas by Johann Friedrich Fasch, Georg Philipp Telemann, Luigi Merci, and Antoine Dard serve as the main focus for examination. In the end, my document will hopefully shed some light on our understanding of bassoon sonatas in the middle half of the eighteenth century and the stylistic diversity that developed over time. ii Copyright © 2017 by Yi-Chen Chiu All rights reserved. -

Le Concert Des Nations

Cal Performances Presents Program Friday, February 27, 2009, 8pm Charles Avison (1709–1770) Concerto IX in Seven Parts, done from the First Congregational Church Harpsichord Lessons by Domenico Scarlatti Largo — Con Spirito — Siciliana — Allegro Le Concert des Nations Antonio Rodriguez de Hita (1725–1787) Música Sinfonica para los Ministriles (1751) Despacio cantable — Andante — Les Goûts Réunis (1670–1780) Pastoral — Allegro Luigi Boccherini (1743–1805) La Musica notturna di Madrid (1780) PROGRAM Le campane di l’Ave Maria — Il tamburo dei Soldati Minuetto dei Ciechi “con mala grazia” Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632–1687) Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme Suite Il Rosario Largo assai — Allegro — Marche pour la Cérémonie des Turcs Largo come prima 1st Air des Espagnols — 2nd Air des Espagnols Passa calle Allegro vivo — Il tamburo Gavotte — Canarie Ritirata Maestoso L’entrée des Scaramouches Chaconne des Scaramouches Le Concert des Nations Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber (1644–1704) Battalia à 10 Das liederliche Schwärmen, Mars, die Schlacht, Manfredo Kraemer concertino undt Lamento der Verwundten, mit Arien Riccardo Minasi violin I imitirt und Baccho dedieirt Mauro Lopez violin II Isabel Serrano, Alba Roca violins Sonata Laura Johnson violin & viola Die liederliche Gesellschaft von allerley Humor Angelo Bartoletti, Gianni da Rosa viols Presto — Der Mars — Presto Jordi Savall viola da gamba Aria — Die Schlacht Balasz Mate, Antoine Ladrette cellos Lamento der Verwundten Musquetirer Xavier Puertas violone Enrique Solinis guitar & theorb0 Luca Guglielmi harpsichord Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713) Concerto IV in Re maggiore (1712) David Mayoral percussion Adagio — Allegro Adagio — Vivace Jordi Savall, director Allegro — Allegro North American representation for Jordi Savall and Le Concert des Nations: INTERMISSION Jon Aaron, Aaron Concert Artists, Inc., New York, New York, www.aaronconcert.com.