NOTES on the PROGRAM by Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

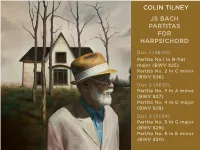

Js Bach Partitas for Harpsichord Colin Tilney

COLIN TILNEY JS BACH PARTITAS FOR HARPSICHORD Disc 1 (48:34) Partita No.1 in B-flat major (BWV 825) Partita No. 2 in C minor (BWV 826) Disc 2 (56:51) Partita No. 3 in A minor (BWV 827) Partita No. 4 in D major (BWV 828) Disc 3 (51:54) Partita No. 5 in G major (BWV 829) Partita No. 6 in E minor (BWV 830) COLIN TILNEY js bach partitas for harpsichord Disc 1 (48:34) Disc 2 (56:51) Disc 3 (51:54) Partita No.1 in B-flat major (BWV 825) Partita No. 3 in A minor (BWV 827) Partita No. 5 in G major (BWV 829) 1. 1. Præludium 2:24 Fantasia 3:17 1. Præambulum 3:14 2. 2. Allemande 4:59 Allemande 3:19 2. Allemande 2:55 3. 3. Corrente 4:09 Corrente 2:12 3. Corrente 2:49 4. Sarabande 6:16 4. Sarabande 3:54 4. Sarabande 4:11 5. Menuets 1 & 2 3:30 5. Burlesca 2:59 5. Tempo di Minuetta 2:30 6. Gigue 3:48 6. Scherzo 1:50 6. Passepied 2:24 7. Gigue 5:34 7. Gigue 3:24 Partita No. 2 in C minor (BWV 826) Partita No. 4 in D major (BWV 828) 7. Sinfonia 5:50 Partita No. 6 in E minor (BWV 830) 8. Ouverture 7:57 8. Allemande 5:32 8. Toccata 8:24 9. Allemande 6:12 9. Courante 3:34 9. Allemanda 4:33 10. Courante 5:16 10. Sarabande 3:34 10. Corrente 3:24 11. -

Franz Schubert's Impromptus D. 899 and D. 935: An

FRANZ SCHUBERT’S IMPROMPTUS D. 899 AND D. 935: AN HISTORICAL AND STYLISTIC STUDY A doctoral document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2005 by Ina Ham M.M., Cleveland Institute of Music, 1999 M.M., Seoul National University, 1996 B.M., Seoul National University, 1994 Committee Chair: Dr. Melinda Boyd ABSTRACT The impromptu is one of the new genres that was conceived in the early nineteenth century. Schubert’s two sets of impromptus D. 899 and D. 935 are among the most important examples to define this new genre and to represent the composer’s piano writing style. Although his two sets of four impromptus have been favored in concerts by both the pianists and the audience, there has been a lack of comprehensive study of them as continuous sets. Since the tonal interdependence between the impromptus of each set suggests their cyclic aspects, Schubert’s impromptus need to be considered and be performed as continuous sets. The purpose of this document is to provide useful resources and performance guidelines to Schubert’s two sets of impromptus D. 899 and D. 935 by examining their historical and stylistic features. The document is organized into three chapters. The first chapter traces a brief history of the impromptu as a genre of piano music, including the impromptus by Jan Hugo Voŕišek as the first pieces in this genre. -

Andras Schiff Franz Schubert Sonatas & Impromptus

Andras Schiff Franz Schubert Sonatas & Impromptus -• ECM NEW SERIES Franz Schubert Vier Impromptus D 899 Sonate in c-Moll D 958 Drei Klavierstücke D 946 Sonate in A-Dur D 959 Andräs Schiff Fortepiano Franz Schubert (1797-1828) II 1-4 Vier Impromptus D899 1-3 Drei Klavierstücke D 946 Allegro molto moderato in c-Moll 9:32 Allegro assai in es-Moll 9:12 Allegro in Es-Dur 4:39 Allegretto in Es-Dur 11 :46 Andante in Ges-Dur 4:59 Allegro in C-Dur 5:31 Allegretto in As-Dur 7: 21 4-7 Sonate in A-Dur D959 5-8 Sonate in c-Moll D958 Allegro 15:45 Allegro 10:35 Andantino 7:13 Adagio 7:00 Scherzo. Allegro vivace - Trio 5:30 Menuett. Allegretto - Trio 3:04 Rondo. Allegretto 12:35 Allegro 9:13 Beethoven's sphere "Secretly, I hope to be able to make something of myself, but who can do any thing after Beethoven?" Schubert's remark, allegedly made to his childhood friendJosef von Spaun, gives us an indication of how strongly he feit himself to be in the shadow of the great composer he was too inhibited ever to approach. For his part, Beethoven cannot have been unaware of Schubert's presence in Vienna. The younger composer's first piano sonata to appear in print - the Sonata in A minor D 845 - bore a dedication to Beethoven's most generous and ardent pa tron, Archduke Rudolph of Austria. Moreover, the work was favourably reviewed in the Leipzig Al/gemeine musikalische Zeitung - a journal which Beethoven is known to have read. -

The Functions of Harmonic Motives in Schubert's Sonata Forms1 Brian

The Functions of Harmonic Motives in Schubert’s Sonata Forms1 Brian Black Schubert’s sonata forms often seem to be animated by some hidden process that breaks to the surface at significant moments, only to subside again as suddenly and enigmatically as it first appeared. Such intrusions usually highlight a specific harmonic motive—either a single chord or a larger multi-chord cell—each return of which draws in the listener, like a veiled prophecy or the distant recall of a thought from the depths of memory. The effect is summed up by Joseph Kerman in his remarks on the unsettling trill on Gß and its repeated appearances throughout the first movement of the Piano Sonata in Bß major, D. 960: “But the figure does not develop, certainly not in any Beethovenian sense. The passage... is superb, but the figure remains essentially what it was at the beginning: a mysterious, impressive, cryptic, Romantic gesture.”2 The allusive way in which Schubert conjures up recurring harmonic motives stamps his music with the mystery and yearning that are the hallmarks of his style. Yet these motives amount to much more than oracular pronouncements, arising without any apparent cause and disappearing without any tangible effect. Quite the contrary—they are actively involved in the unfolding of the 1 This article is dedicated to William E. Caplin. I would also like to thank two of my colleagues at the University of Lethbridge, Deanna Oye and Edward Jurkowski, for their many helpful suggestions during the article’s preparation. 2 Joseph Kerman “A Romantic Detail in Schubert’s Schwanengesang,” in Walter Frisch (ed.), Schubert: Critical and Analytical Perspectives, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986): 59. -

Franz Schubert

FRANZ SCHUBERT Foreword . 3 About the Composer . 3 Contents Schubert’s Piano Music . 3 About This Edition . 4 About the Music . 5 Moments Musicaux, Op . 94 (D . 780) . 5 Impromptus, Op . 90 (D . 899) . 7 Impromptus, Op . 142 (D . 935) . 9 Recommended Reading . 12 Recommended Listening . 12 Acknowledgments . 12 MOMENTS MUSICAUX, Op . 94 (D . 780) No . 1 (C major) . 13 No . 2 (A-flat major) . 16 No . 3 (F minor) . 20 No . 4 (C-sharp minor) . 22 No . 5 (F minor) . 26 No . 6 (A-flat major) . 29 IMPROMPTUS, Op . 90 (D . 899) No . 1 (C minor) . 32 No . 2 (E-flat major) . 43 No . 3 (G-flat major) . 49 No . 4 (A-flat major) . 57 IMPROMPTUS, Op . 142 (D . 935) No . 1 (F minor) . 68 No . 2 (A-flat major) . 83 No . 3 (B-flat major) . 88 No . 4 (F minor) . 99 2 Moments Musicaux, Op. 94 Impromptus, Opp. 90 & 142 Edited by Murray Baylor SCHUBERT’S PIANO MUSIC Schubert’s music seems to fall between Classical and Foreword Romantic classifications—perhaps between that of Beethoven and Chopin . Although he first became known in Vienna as a composer of lieder, the piano was his instrument, and he wrote some of his finest music for piano solo and piano duet . The kind of instrument he played, however, usually called a fortepiano, was ABOUT THE COMPOSER very different from a modern Steinway . In the Kunsthis- torische Museum in Vienna, there is a well-maintained Of the many famous composers who lived and worked piano that he once owned . Its compass is from the F an in Vienna, Europe’s most musical city, Franz Schubert octave below the bass staff to the F two octaves above was the only one who made his home there from birth the treble—six octaves in all . -

Baroque and Classical Style in Selected Organ Works of The

BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL STYLE IN SELECTED ORGAN WORKS OF THE BACHSCHULE by DEAN B. McINTYRE, B.A., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee Accepted Dearri of the Graduate jSchool December, 1998 © Copyright 1998 Dean B. Mclntyre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for the general guidance and specific suggestions offered by members of my dissertation advisory committee: Dr. Paul Cutter and Dr. Thomas Hughes (Music), Dr. John Stinespring (Art), and Dr. Daniel Nathan (Philosophy). Each offered assistance and insight from his own specific area as well as the general field of Fine Arts. I offer special thanks and appreciation to my committee chairperson Dr. Wayne Hobbs (Music), whose oversight and direction were invaluable. I must also acknowledge those individuals and publishers who have granted permission to include copyrighted musical materials in whole or in part: Concordia Publishing House, Lorenz Corporation, C. F. Peters Corporation, Oliver Ditson/Theodore Presser Company, Oxford University Press, Breitkopf & Hartel, and Dr. David Mulbury of the University of Cincinnati. A final offering of thanks goes to my wife, Karen, and our daughter, Noelle. Their unfailing patience and understanding were equalled by their continual spirit of encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT ix LIST OF TABLES xi LIST OF FIGURES xii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES xiii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xvi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 11. BAROQUE STYLE 12 Greneral Style Characteristics of the Late Baroque 13 Melody 15 Harmony 15 Rhythm 16 Form 17 Texture 18 Dynamics 19 J. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

Dance Topics I: Music and Dance in the Ancien Régime

Dance Topics I: Music and Dance in the Ancien Régime Lawrence M. Zbikowski University of Chicago, Department of Music [this is a draft of a contribution to the Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory, ed. Danuta Mirka, which is presently under review] In 1777, Johann Philipp Kirnberger paused in the production of his monumental Die Kunst des reinen Satzes in der Musik to publish a Recueil d’airs de danse caractéristiques. On the one hand, the relationship between the modest dances of Kirnberger’s collection and the careful, methodical setting out of the art of strict musical composition is not immediately evident, as the two seem to belong to rather different intellectual registers. On the other hand, there is evidence that, for Kirnberger, the relationship between the two works was quite intimate. As the preface to the Recueil makes clear, the twenty-odd dances gathered by Kirnberger were meant to set out for the young musician the characteristic features of different dance types, as he believed familiarity with these was essential to understanding musical organization. In order to acquire the necessary qualities for a good performance, the musician can do nothing better than diligently play all sorts of characteristic dances. Each dance has its own rhythm, its passages of the same length, its accents on particular places in each measure; one thus easily recognizes them, and becomes accustomed, through playing them often, to attribute to each its particular rhythm, and to mark its patterns of measures and accents, so that one recognizes easily, in a long piece of music, the rhythms, sections and accents, so different from each other and so mixed up together. -

Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano Amy Jun Ming Chin Minnesota State University - Mankato

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects 2012 Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano Amy Jun Ming Chin Minnesota State University - Mankato Follow this and additional works at: http://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Chin, Amy Jun Ming, "Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano" (2012). Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects. Paper 195. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano By Amy J. Chin Program Notes Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music In Piano Performance Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota April 2012 Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano Amy Jun Ming Chin This program notes has been examined and approved by the following members of the program notes committee. Dr. David Viscoli, Advisor Dr.Linda B. Duckett Dr. Karen Boubel Preface The purpose of this paper is to offer a biographical background of the composers, and historical and theoretical analysis of the works performed in my Master’s recital. This will assist the listener to better understand the music performed. Acknowledgements I would like to thank members of my examining committee, Dr. -

HPPAD Advanced Levels A1 A2 Advanced 1

HPPAD Advanced Levels A1 A2 Advanced 1 TECHNIQUE: Scales: All Major and minor scales (in three forms as in Intermediate levels), 4 octaves parallel, HT All Major Scales, 2 octaves Contrary Chromatic Scale 4 octaves Hands Together, starting on any note Chords: I-IV-I-V7-I Cadence in root position and first inversion; bass line, pedal Tonic Triad Inversions blocked and broken, HT (see Intermediate 2) Arpeggios: All Major and Minor scales keys, in root position and 1st inversion, 4 octaves HT Sight Level of Difficulty Time Approximate Keys reading: signature length Intermediate 1 2 3 4 6 Eight Major and minor keys up to three repertoire 4 4 4 8 measures sharps or three flats REPERTOIRE: 2 pieces required; 3 pieces optional; Inclusion of a Sonatina/Sonata movement, is highly recommended; assessment of repertoire performances will be memory neutral Bach, French Suites, easier selections; Two-Part Inventions Mozart, Sonata K.545; Beethoven, Sonata Op. 49 No. 1 Schubert, Scherzo in B Flat Major, selections from Impromptus and Moment Musicaux Schumann, Children’s Sonata op. 118; Grieg, Lyric Pieces, more advanced Chopin, Polonaises in g minor and B Flat Major, Preludes Op. 28, easier selections Kabalevsky, Rondos, Op. 60 (selections); McDowell, Woodland Sketches, Op. 51 Mendelssohn, Songs without Words, Op. 30, selections (N. 3, 6) Schumann, Op. 124, selections (Fantastic Dance) Prokofiev, Music for Children, Op. 65, more difficult selections Other comparable material Advanced 2 TECHNIQUE: Scales: All Majors and minors, 4 octaves -

Lunchtime Concert Slava Grigoryan Guitar Sharon Grigoryan Cello

Sharon Grigoryan has been the cellist with the Australian String Quartet since 2013, and has been invited to be Guest Principal Cellist with the Melbourne, Adelaide and Tasmanian Symphony Orchestras. She is the current Artistic Director of the Barossa, Baroque and Beyond music festival, which recently completed its fifth year. In 2019 Sharon curated a chamber music series, Live at the Quartet Bar, for the Adelaide Festival Centre, and made her debut as a radio presenter on ABC Classic. Regarded as a wizard of the guitar, Slava Grigoryan has forged a prolific reputation as a classical guitar virtuoso. Born in Kazakhstan, he immigrated with his family to Australia in 1981 and began studying the guitar with his violinist father Edward at the age of 6. By the time he was 17 he was signed to the Sony Classical Label. His relationship with Sony Classical, ABC Classic in Australia, ECM in Germany and his own label Which Way Music has led to the release of over 30 solo and collaborative albums – four of which have won ARIA Awards – spanning a vast range of musical genres. Since 2009 Slava has been the Artistic Director of the Adelaide Guitar Festival. Lunchtime Concert Slava Grigoryan guitar Sharon Grigoryan cello Friday 25 September, 1:10pm Throughout, Bach’s contrapuntal genius shows in his ability to project multiple PROGRAM voices and implied harmonies with what is often considered a single-line Jobiniana No. 4 Sergio Assad instrument. Maurice Ravel’s Pièce en forme de Habanera was actually originally written as a Sarabande from Cello Suite No. -

Emanuel Ax, Piano

Sunday, January 22, 2017, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Emanuel Ax, piano PROGRAM Franz SCHUBERT (1797 –1828) Four Impromptus, D. 935 (Op. 142) No. 1 in F minor No. 2 in A-flat Major No. 3 in B-flat Major No. 4 in F minor Frédéric CHOPIN (1810 –1849) Impromptus No. 1 in A-flat Major, Op. 29 No. 2 in F-sharp Major, Op. 36 No. 3 in G-flat Major, Op. 51 Fantaisie-Impromptu in C-sharp minor, Op. 66 INTERMISSION SCHUBERT Klavierstück No. 2 in E-flat Major, D. 946 CHOPIN Sonata No. 3 in B minor, Op. 58 Allegro maestoso Scherzo: Molto vivace Largo Finale: Presto non tanto Funded, in part, by the Koret Foundation, this performance is part of Cal Performances’ 2016/17 Koret Recital Series, which brings world-class artists to our community. Additional support made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsors Diana Cohen and Bill Falik. Steinway Piano PROGRAM NOTES Four Impromptus, D. 935 (Op. 142) C Major, the last three piano sonatas, the String Franz Schubert Quintet, the two piano trios, the Impromp tus— On January 31, 1827, Franz Schubert turned 30. that he created during the last months of his He had been following a bohemian existence brief life. in Vienna for over a decade, making barely Schubert began his eight pieces titled more than a pittance from the sale and per - Impromptu in the summer and autumn of formance of his works, and living largely off 1827; they were completed by December. He the generosity of his friends, a devoted band of did not invent the title.