Silvius Leopold Weiss the Complete London Manuscript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

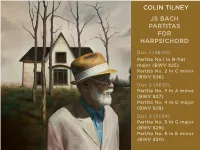

Js Bach Partitas for Harpsichord Colin Tilney

COLIN TILNEY JS BACH PARTITAS FOR HARPSICHORD Disc 1 (48:34) Partita No.1 in B-flat major (BWV 825) Partita No. 2 in C minor (BWV 826) Disc 2 (56:51) Partita No. 3 in A minor (BWV 827) Partita No. 4 in D major (BWV 828) Disc 3 (51:54) Partita No. 5 in G major (BWV 829) Partita No. 6 in E minor (BWV 830) COLIN TILNEY js bach partitas for harpsichord Disc 1 (48:34) Disc 2 (56:51) Disc 3 (51:54) Partita No.1 in B-flat major (BWV 825) Partita No. 3 in A minor (BWV 827) Partita No. 5 in G major (BWV 829) 1. 1. Præludium 2:24 Fantasia 3:17 1. Præambulum 3:14 2. 2. Allemande 4:59 Allemande 3:19 2. Allemande 2:55 3. 3. Corrente 4:09 Corrente 2:12 3. Corrente 2:49 4. Sarabande 6:16 4. Sarabande 3:54 4. Sarabande 4:11 5. Menuets 1 & 2 3:30 5. Burlesca 2:59 5. Tempo di Minuetta 2:30 6. Gigue 3:48 6. Scherzo 1:50 6. Passepied 2:24 7. Gigue 5:34 7. Gigue 3:24 Partita No. 2 in C minor (BWV 826) Partita No. 4 in D major (BWV 828) 7. Sinfonia 5:50 Partita No. 6 in E minor (BWV 830) 8. Ouverture 7:57 8. Allemande 5:32 8. Toccata 8:24 9. Allemande 6:12 9. Courante 3:34 9. Allemanda 4:33 10. Courante 5:16 10. Sarabande 3:34 10. Corrente 3:24 11. -

Keyboard Music

Prairie View A&M University HenryMusic Library 5/18/2011 KEYBOARD CD 21 The Women’s Philharmonic Angela Cheng, piano Gillian Benet, harp Jo Ann Falletta, conductor Ouverture (Fanny Mendelssohn) Piano Concerto in a minor, Op. 7 (Clara Schumann) Concertino for Harp and Orchestra (Germaine Tailleferre) D’un Soir Triste (Lili Boulanger) D’un Matin de Printemps (Boulanger) CD 23 Pictures for Piano and Percussion Duo Vivace Sonate für Marimba and Klavier (Peter Tanner) Sonatine für drei Pauken und Klavier (Alexander Tscherepnin) Duettino für Vibraphon und Klavier, Op. 82b (Berthold Hummel) The Flea Market—Twelve Little Musical Pictures for Percussion and Piano (Yvonne Desportes) Cross Corners (George Hamilton Green) The Whistler (Green) CD 25 Kaleidoscope—Music by African-American Women Helen Walker-Hill, piano Gregory Walker, violin Sonata (Irene Britton Smith) Three Pieces for Violin and Piano (Dorothy Rudd Moore) Prelude for Piano (Julia Perry) Spring Intermezzo (from Four Seasonal Sketches) (Betty Jackson King) Troubled Water (Margaret Bonds) Pulsations (Lettie Beckon Alston) Before I’d Be a Slave (Undine Smith Moore) Five Interludes (Rachel Eubanks) I. Moderato V. Larghetto Portraits in jazz (Valerie Capers) XII. Cool-Trane VII. Billie’s Song A Summer Day (Lena Johnson McLIn) Etude No. 2 (Regina Harris Baiocchi) Blues Dialogues (Dolores White) Negro Dance, Op. 25 No. 1 (Nora Douglas Holt) Fantasie Negre (Florence Price) CD 29 Riches and Rags Nancy Fierro, piano II Sonata for the Piano (Grazyna Bacewicz) Nocturne in B flat Major (Maria Agata Szymanowska) Nocturne in A flat Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. 19 in C Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. 8 in D Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. -

The Form of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites Daniel E. Prindle University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Prindle, Daniel E., "The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 636. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/636 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2011 Master of Music in Music Theory © Copyright by Daniel E. Prindle 2011 All Rights Reserved ii THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________ Gary Karpinski, Chair _____________________________________ Miriam Whaples, Member _____________________________________ Brent Auerbach, Member ___________________________________ Jeffrey Cox, Department Head Department of Music and Dance iii DEDICATION To Michelle and Rhys. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the generous sacrifice made by my family. -

Harpsichord Suite in a Minor by Élisabeth Jacquet De La Guerre

Harpsichord Suite in A Minor by Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre Arranged for Solo Guitar by David Sewell A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved November 2019 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Frank Koonce, Chair Catalin Rotaru Kotoka Suzuki ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2019 ABSTRACT Transcriptions and arrangements of works originally written for other instruments have greatly expanded the guitar’s repertoire. This project focuses on a new arrangement of the Suite in A Minor by Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre (1665–1729), which originally was composed for harpsichord. The author chose this work because the repertoire for the guitar is critically lacking in examples of French Baroque harpsichord music and also of works by female composers. The suite includes an unmeasured harpsichord prelude––a genre that, to the author’s knowledge, has not been arranged for the modern six-string guitar. This project also contains a brief account of Jacquet de la Guerre’s life, discusses the genre of unmeasured harpsichord preludes, and provides an overview of compositional aspects of the suite. Furthermore, it includes the arrangement methodology, which shows the process of creating an idiomatic arrangement from harpsichord to solo guitar while trying to preserve the integrity of the original work. A summary of the changes in the current arrangement is presented in Appendix B. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my great appreciation to Professor Frank Koonce for his support and valuable advice during the development of this research, and also to the members of my committee, Professor Catalin Rotaru and Dr. -

Inquiry Into J.S. Bach's Method of Reworking in His Composition of the Concerto for Keyboard, Flute and Violin, Bwv 1044, and Its

INQUIRY INTO J.S. BACH'S METHOD OF REWORKING IN HIS COMPOSITION OF THE CONCERTO FOR KEYBOARD, FLUTE AND VIOLIN, BWV 1044, AND ITS CHRONOLOGY by DAVID JAMES DOUGLAS B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1994 A THESIS IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES School of Music We accept this thesis as conforming tjjfe required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 1997 © David James Douglas, 1997 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of ZH t/S fC The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date . DE-6 (2788) Abstract Bach's Concerto for Keyboard, Flute, and Violin with Orchestra in A minor, BWV 1044, is a very interesting and unprecedented case of Bach reworking pre-existing keyboard works into three concerto movements. There are several examples of Bach carrying out the reverse process with his keyboard arrangements of Vivaldi, and other composers' concertos, but the reworking of the Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 894, into the outer movements of BWV 1044, and the second movement of the Organ Sonata in F major, BWV 527, into the middle movement, appears to be unique among Bach's compositional activity. -

Baroque and Classical Style in Selected Organ Works of The

BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL STYLE IN SELECTED ORGAN WORKS OF THE BACHSCHULE by DEAN B. McINTYRE, B.A., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee Accepted Dearri of the Graduate jSchool December, 1998 © Copyright 1998 Dean B. Mclntyre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for the general guidance and specific suggestions offered by members of my dissertation advisory committee: Dr. Paul Cutter and Dr. Thomas Hughes (Music), Dr. John Stinespring (Art), and Dr. Daniel Nathan (Philosophy). Each offered assistance and insight from his own specific area as well as the general field of Fine Arts. I offer special thanks and appreciation to my committee chairperson Dr. Wayne Hobbs (Music), whose oversight and direction were invaluable. I must also acknowledge those individuals and publishers who have granted permission to include copyrighted musical materials in whole or in part: Concordia Publishing House, Lorenz Corporation, C. F. Peters Corporation, Oliver Ditson/Theodore Presser Company, Oxford University Press, Breitkopf & Hartel, and Dr. David Mulbury of the University of Cincinnati. A final offering of thanks goes to my wife, Karen, and our daughter, Noelle. Their unfailing patience and understanding were equalled by their continual spirit of encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT ix LIST OF TABLES xi LIST OF FIGURES xii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES xiii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xvi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 11. BAROQUE STYLE 12 Greneral Style Characteristics of the Late Baroque 13 Melody 15 Harmony 15 Rhythm 16 Form 17 Texture 18 Dynamics 19 J. -

Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Johann Sebastian Bach Born March 21, 1685, Eisenach, Thuringia, Germany. Died July 28, 1750, Leipzig, Germany. Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068 Although the dating of Bach’s four orchestral suites is uncertain, the third was probably written in 1731. The score calls for two oboes, three trumpets, timpani, and harpsichord, with strings and basso continuo. Performance time is approximately twenty -one minutes. The Chicago Sympho ny Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Bach’s Third Orchestral Suite were given at the Auditorium Theatre on October 23 and 24, 1891, with Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on May 15 , 16, 17, and 20, 2003, with Jaime Laredo conducting. The Orchestra first performed the Air and Gavotte from this suite at the Ravinia Festival on June 29, 1941, with Frederick Stock conducting; the complete suite was first performed at Ravinia on August 5 , 1948, with Pierre Monteux conducting, and most recently on August 28, 2000, with Vladimir Feltsman conducting. When the young Mendelssohn played the first movement of Bach’s Third Orchestral Suite on the piano for Goethe, the poet said he could see “a p rocession of elegantly dressed people proceeding down a great staircase.” Bach’s music was nearly forgotten in 1830, and Goethe, never having heard this suite before, can be forgiven for wanting to attach a visual image to such stately and sweeping music. Today it’s hard to imagine a time when Bach’s name meant little to music lovers and when these four orchestral suites weren’t considered landmarks. -

PROGRAM NOTES Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 1 in C

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Johann Sebastian Bach Born March 21, 1685, Eisenach, Thuringia, Germany. Died July 28, 1750, Leipzig, Germany. Orchestral Suite No. 1 in C Major, BWV 1066 The dating of Bach’s four orche stral suites is uncertain. The first and fourth are the earliest, both composed around 1725. Suite no. 1 calls for two oboes and bassoon, with strings and continuo . Performance time is approximately twenty -one minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s fir st subscription concert performances of Bach’s First Orchestral Suite were given at Orchestra Hall on February 22 and 23, 1951, with Rafael Kubelík conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on May 15, 16, and 17, 2003, with D aniel Barenboim conducting. Today it’s hard to imagine a time when Bach’s name meant little to music lovers, and when his four orchestral suites weren’t considered landmarks. But in the years immediately following Bach’s death in 1750, public knowledge o f his music was nil, even though other, more cosmopolitan composers, such as Handel, who died only nine years later, remained popular. It’s Mendelssohn who gets the credit for the rediscovery of Bach’s music, launched in 1829 by his revival of the Saint Ma tthew Passion in Berlin. A great deal of Bach’s music survives, but incredibly, there’s much more that didn’t. Christoph Wolff, today’s finest Bach biographer, speculates that over two hundred compositions from the Weimar years are lost, and that just 15 to 20 percent of Bach’s output from his subsequent time in Cöthen has survived. -

J. S. Bach's Six Unaccompanied Cello Suites: What Did Bach Want?

1 J. S. Bach’s Six Unaccompanied Cello Suites: What did Bach Want? Brooke Mickelson Composers of the Baroque period are known to have maintained a level of detachment from their music, writing scores absent of many now commonplace musical notations. This creates a problem for modern musicians who want to understand the composer’s vision. This analysis is driven by a call to understand Bach’s intended style for the six cello suites, debunking main controversies over the cello suites’ composition and discussing how its style features can be portrayed in performance. The Bachs and Origins of the Cello Suites The Bachs were a German family of amateur musicians who played in the church and the community. Johann Sebastian’s career began in this Bach tradition, playing organ in Lutheran churches, and he was one of a few family members to become a professional. He showed exceptional talent in improvisation and composition, and around age 20 became the church organist for the court in Weimar. In this first period, he composed organ and choral music for church services and events. 1 Looking for a change, Bach moved to become capellmeister (music director) for the court in Cöthen, where the prince was an amateur musician attempting to bring music into his court. This is considered his “instrumental period” because of Bach’s greater output of instrumental music to please the prince. Scholars believe that he composed the violin sonatas and partitas and the cello suites in this period. Finally, he moved to Leipzig to work as cantor (choir master) of Saint Thomas’s Church. -

Exploring the Limits: the Tonal, the Gestural, and the Allegorical in Bach’S Musical Offering 1

Understanding Bach, 1, 19-38 © Bach Network UK 2006 Exploring the Limits: the Tonal, the Gestural, and the Allegorical in Bach’s 1 Musical Offering RUTH HACOHEN Analogies and alternatives Analogies are powerful cognitive mechanisms for adapting, constructing, and generating knowledge. Their power lies in their ability to transfer structured information from a familiar to an unfamiliar domain, helping us to explore new contexts, craft new tools, and accustom ourselves to new experiences. An elaborate scheme of relations, functions, and trajectories, studied in relation to a certain object, programme, or process, enables us ‘to see through’ an opaque target, while articulating its logic and form. Explicating the tacit, analogies often bounce back on their original, ‘modelling’ object, revealing in it, through comparative wisdom, unfathomed configurations and hidden tendencies. Analogies thus resemble metaphors, but are more deliberate and systematic, open to criticism as well as revision. 2 As object, programme, and process, music has always been a fertile ground for fruitful and compelling analogies. Whether scientific, linguistic, or emotional, analogies have assisted in the perception and conception of musical strategies and structures. At the same time internal musical schemes have been replanted onto the original modelling realms, facilitating in them new modes of understanding 1 This article was completed at a distance of few kilometres from Potsdam, during my stay at the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin, in the academic year 2004-05. I am grateful to Galit Hasan- Rokem and to Lydia Liu for their inspiring comments on this paper. 2 The literature on this subject, in relation to cognition and science, is vast. -

Brandenburg Concerto No. 3, 3Rd Movement

BRANDENBURG CONCERTO No. 3 rd (3 movement: “Allegro”) 2 J. S. Bach (1718) BRANDENBURG CONCERTO NO. 3 3rd movement, “Allegro” By Johann Sebastian Bach (Germany) Baroque (ca. 1718) LESSON INTRODUCTION Important Terms and Concepts ∗ Concerto grosso: a type of piece in which multiple soloists perform with an orchestra ∗ Major scale: A scale is an ordered succession of pitches, arranged in a specific pattern of whole (W) or half (H) steps. A major scale follows the pattern WWHWWWH and is often sung as “Do Re Mi Fa Sol La Ti Do” ∗ Tempo: the speed of music o Adagio: slow, stately, leisurely o Allegro: quickly BEHIND THE MUSIC Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 – 1782) is widely considered to be one of the most important composers in the history of Western music. His father was a The Discovery concerts on respected violinist and January 26 - 27, 2017, will violist, but both his feature J. S. Bach’s “Air “ from mother and father died Symphonic Suite No. 3. when he was around 10 Register your class for this free concert today!! years old. Bach moved in with his brother, who was a professional church organist, and in the Amplify Curriculum: copyright 2016 Shreveport Symphony Orchestra www.shreveportsymphony.com 3 following years, he studied organ, clavichord, violin, and composition of music. Bach later served for the courts, where he was obligated to compose a great deal of instrumental music: hundreds of pieces for solo keyboard, concertos, orchestral dance suites, and more! In a tribute to the Duke of Brandenburg in 1721, Bach created the "Brandenburg Concertos.” These concertos represent a popular music style of the Baroque era, the concerto grosso, in which a group of soloists play with a small orchestra. -

'Modern Baroque'

‘Modern Baroque’ ‘Approaches and Attitudes to Baroque Music Performance on the Saxophone’ Jonathan Byrnes 4080160 Masters of Music Projecto Cientifico IV ESMAE 2010 1 Contents Page ‘Introduction’ (Prelude) 4 ‘Education’ (Allemande) 7 ‘Performance’ (Courante) 12 ‘Morality – Responsibility and Reasons.’ (Sarabande) 18 ‘Transcription or adaptation’ – note for note transcription (Minuet I) 36 ‘Transcription or adaptation’ – adaptation (Minuet II) 58 Conclusion (Gigue) 70 ‘Bibliography’ 73 ‘Discography’ 77 ‘Internet Resourses’ 78 2 Thank you. This Masters Thesis would not have been possible without the help and assistance from the people below. I would like to thank them sincerely for all their guidence and support. Sofia Lourenço, Henk Van Twillert, Fernando Ramos, Gilberto Bernardes, Madelena Soveral, Dr. Cecília, Filipe Fonseca, Luís Lima, Nicholas Russoniello, Cláudio Dioguardi, Cármen Nieves, Alexander Brito, Donny McKenzie, Andy Harper, Thom Chapman, Alana Blackburn, Paul Leenhouts, Harry White, And of course my family. Without these people, I am sure I would not have achieved this work. 3 1. Introduction (Prelude) Baroque music has been part of the saxophone repertoire in one form or another since the instruments creation, as it so happened to coincide with the Baroque revival. ‘It was Mendelssohn's promotion of the St Matthew Passion in 1829 which marked the first public "revival" of Bach and his music’ 1, either through studies or repertoire the music of the baroque period has had an important role in the development of the majority of all saxophonists today. However the question remains. What function does this music have for a modern instrumentalist and how should this music be used or performed by a saxophonist? Many accolades have been given of saxophone performances of Baroque music.