Eugene Drucker in Recital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

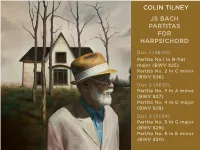

Js Bach Partitas for Harpsichord Colin Tilney

COLIN TILNEY JS BACH PARTITAS FOR HARPSICHORD Disc 1 (48:34) Partita No.1 in B-flat major (BWV 825) Partita No. 2 in C minor (BWV 826) Disc 2 (56:51) Partita No. 3 in A minor (BWV 827) Partita No. 4 in D major (BWV 828) Disc 3 (51:54) Partita No. 5 in G major (BWV 829) Partita No. 6 in E minor (BWV 830) COLIN TILNEY js bach partitas for harpsichord Disc 1 (48:34) Disc 2 (56:51) Disc 3 (51:54) Partita No.1 in B-flat major (BWV 825) Partita No. 3 in A minor (BWV 827) Partita No. 5 in G major (BWV 829) 1. 1. Præludium 2:24 Fantasia 3:17 1. Præambulum 3:14 2. 2. Allemande 4:59 Allemande 3:19 2. Allemande 2:55 3. 3. Corrente 4:09 Corrente 2:12 3. Corrente 2:49 4. Sarabande 6:16 4. Sarabande 3:54 4. Sarabande 4:11 5. Menuets 1 & 2 3:30 5. Burlesca 2:59 5. Tempo di Minuetta 2:30 6. Gigue 3:48 6. Scherzo 1:50 6. Passepied 2:24 7. Gigue 5:34 7. Gigue 3:24 Partita No. 2 in C minor (BWV 826) Partita No. 4 in D major (BWV 828) 7. Sinfonia 5:50 Partita No. 6 in E minor (BWV 830) 8. Ouverture 7:57 8. Allemande 5:32 8. Toccata 8:24 9. Allemande 6:12 9. Courante 3:34 9. Allemanda 4:33 10. Courante 5:16 10. Sarabande 3:34 10. Corrente 3:24 11. -

Keyboard Music

Prairie View A&M University HenryMusic Library 5/18/2011 KEYBOARD CD 21 The Women’s Philharmonic Angela Cheng, piano Gillian Benet, harp Jo Ann Falletta, conductor Ouverture (Fanny Mendelssohn) Piano Concerto in a minor, Op. 7 (Clara Schumann) Concertino for Harp and Orchestra (Germaine Tailleferre) D’un Soir Triste (Lili Boulanger) D’un Matin de Printemps (Boulanger) CD 23 Pictures for Piano and Percussion Duo Vivace Sonate für Marimba and Klavier (Peter Tanner) Sonatine für drei Pauken und Klavier (Alexander Tscherepnin) Duettino für Vibraphon und Klavier, Op. 82b (Berthold Hummel) The Flea Market—Twelve Little Musical Pictures for Percussion and Piano (Yvonne Desportes) Cross Corners (George Hamilton Green) The Whistler (Green) CD 25 Kaleidoscope—Music by African-American Women Helen Walker-Hill, piano Gregory Walker, violin Sonata (Irene Britton Smith) Three Pieces for Violin and Piano (Dorothy Rudd Moore) Prelude for Piano (Julia Perry) Spring Intermezzo (from Four Seasonal Sketches) (Betty Jackson King) Troubled Water (Margaret Bonds) Pulsations (Lettie Beckon Alston) Before I’d Be a Slave (Undine Smith Moore) Five Interludes (Rachel Eubanks) I. Moderato V. Larghetto Portraits in jazz (Valerie Capers) XII. Cool-Trane VII. Billie’s Song A Summer Day (Lena Johnson McLIn) Etude No. 2 (Regina Harris Baiocchi) Blues Dialogues (Dolores White) Negro Dance, Op. 25 No. 1 (Nora Douglas Holt) Fantasie Negre (Florence Price) CD 29 Riches and Rags Nancy Fierro, piano II Sonata for the Piano (Grazyna Bacewicz) Nocturne in B flat Major (Maria Agata Szymanowska) Nocturne in A flat Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. 19 in C Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. 8 in D Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. -

The Form of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites Daniel E. Prindle University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Prindle, Daniel E., "The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 636. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/636 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2011 Master of Music in Music Theory © Copyright by Daniel E. Prindle 2011 All Rights Reserved ii THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________ Gary Karpinski, Chair _____________________________________ Miriam Whaples, Member _____________________________________ Brent Auerbach, Member ___________________________________ Jeffrey Cox, Department Head Department of Music and Dance iii DEDICATION To Michelle and Rhys. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the generous sacrifice made by my family. -

New on Naxos | MAY 2012

25years NEW ON The World’s Leading ClassicalNA MusicXO LabelS MAY 2012 This Month’s Other Highlights © 2012 Naxos Rights International Limited • Contact Us: [email protected] www.naxos.com • www.classicsonline.com • www.naxosmusiclibrary.com NEW ON NAXOS | MAY 2012 8.572823 Playing Time: 76:43 7 47313 28237 1 © Bruna Rausa Alessandro Marangoni Mario CASTELNUOVO-TEDESCO (1895-1968) Piano Concerto No 1 in G minor, Op 46 Piano Concerto No 2 in F major, Op 92 Four Dances from ‘Love’s Labour’s Lost’, Op 167* Alessandro Marangoni, piano Malmö Symphony Orchestra • Andrew Mogrelia * First Performance and Recording Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s two Piano Concertos form a contrasting pair. Concerto No. 1, written in 1927, is a vivid and witty example of his romantic spirit, exquisite melodies and rich yet transparent orchestration. Concerto No. 2, composed a decade later, is a darker, more dramatic and virtuosic work. The deeply-felt and dreamlike slow movement and passionate finale are tinged with bleak moments of somber agitation, suggestive of unfolding tragic events with the imminent introduction of the Fascist Racial Laws that led Castelnuovo-Tedesco to seek exile in the USA in 1939. The Four Dances from ‘Love’s Labour’s Lost’, part of the composer’s recurring fascination for the art of Shakespeare, are atmospheric, richly characterised and hugely enjoyable. This is their first performance and recording. After winning national and international awards, Alessandro Marangoni has appeared throughout Europe and America, as a soloist and as a © Zu Zweit chamber musician, collaborating with some of Italy’s leading performers. -

Harpsichord Suite in a Minor by Élisabeth Jacquet De La Guerre

Harpsichord Suite in A Minor by Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre Arranged for Solo Guitar by David Sewell A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved November 2019 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Frank Koonce, Chair Catalin Rotaru Kotoka Suzuki ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2019 ABSTRACT Transcriptions and arrangements of works originally written for other instruments have greatly expanded the guitar’s repertoire. This project focuses on a new arrangement of the Suite in A Minor by Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre (1665–1729), which originally was composed for harpsichord. The author chose this work because the repertoire for the guitar is critically lacking in examples of French Baroque harpsichord music and also of works by female composers. The suite includes an unmeasured harpsichord prelude––a genre that, to the author’s knowledge, has not been arranged for the modern six-string guitar. This project also contains a brief account of Jacquet de la Guerre’s life, discusses the genre of unmeasured harpsichord preludes, and provides an overview of compositional aspects of the suite. Furthermore, it includes the arrangement methodology, which shows the process of creating an idiomatic arrangement from harpsichord to solo guitar while trying to preserve the integrity of the original work. A summary of the changes in the current arrangement is presented in Appendix B. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my great appreciation to Professor Frank Koonce for his support and valuable advice during the development of this research, and also to the members of my committee, Professor Catalin Rotaru and Dr. -

Inquiry Into J.S. Bach's Method of Reworking in His Composition of the Concerto for Keyboard, Flute and Violin, Bwv 1044, and Its

INQUIRY INTO J.S. BACH'S METHOD OF REWORKING IN HIS COMPOSITION OF THE CONCERTO FOR KEYBOARD, FLUTE AND VIOLIN, BWV 1044, AND ITS CHRONOLOGY by DAVID JAMES DOUGLAS B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1994 A THESIS IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES School of Music We accept this thesis as conforming tjjfe required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 1997 © David James Douglas, 1997 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of ZH t/S fC The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date . DE-6 (2788) Abstract Bach's Concerto for Keyboard, Flute, and Violin with Orchestra in A minor, BWV 1044, is a very interesting and unprecedented case of Bach reworking pre-existing keyboard works into three concerto movements. There are several examples of Bach carrying out the reverse process with his keyboard arrangements of Vivaldi, and other composers' concertos, but the reworking of the Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 894, into the outer movements of BWV 1044, and the second movement of the Organ Sonata in F major, BWV 527, into the middle movement, appears to be unique among Bach's compositional activity. -

Baroque and Classical Style in Selected Organ Works of The

BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL STYLE IN SELECTED ORGAN WORKS OF THE BACHSCHULE by DEAN B. McINTYRE, B.A., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee Accepted Dearri of the Graduate jSchool December, 1998 © Copyright 1998 Dean B. Mclntyre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for the general guidance and specific suggestions offered by members of my dissertation advisory committee: Dr. Paul Cutter and Dr. Thomas Hughes (Music), Dr. John Stinespring (Art), and Dr. Daniel Nathan (Philosophy). Each offered assistance and insight from his own specific area as well as the general field of Fine Arts. I offer special thanks and appreciation to my committee chairperson Dr. Wayne Hobbs (Music), whose oversight and direction were invaluable. I must also acknowledge those individuals and publishers who have granted permission to include copyrighted musical materials in whole or in part: Concordia Publishing House, Lorenz Corporation, C. F. Peters Corporation, Oliver Ditson/Theodore Presser Company, Oxford University Press, Breitkopf & Hartel, and Dr. David Mulbury of the University of Cincinnati. A final offering of thanks goes to my wife, Karen, and our daughter, Noelle. Their unfailing patience and understanding were equalled by their continual spirit of encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT ix LIST OF TABLES xi LIST OF FIGURES xii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES xiii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xvi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 11. BAROQUE STYLE 12 Greneral Style Characteristics of the Late Baroque 13 Melody 15 Harmony 15 Rhythm 16 Form 17 Texture 18 Dynamics 19 J. -

Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Johann Sebastian Bach Born March 21, 1685, Eisenach, Thuringia, Germany. Died July 28, 1750, Leipzig, Germany. Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068 Although the dating of Bach’s four orchestral suites is uncertain, the third was probably written in 1731. The score calls for two oboes, three trumpets, timpani, and harpsichord, with strings and basso continuo. Performance time is approximately twenty -one minutes. The Chicago Sympho ny Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Bach’s Third Orchestral Suite were given at the Auditorium Theatre on October 23 and 24, 1891, with Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on May 15 , 16, 17, and 20, 2003, with Jaime Laredo conducting. The Orchestra first performed the Air and Gavotte from this suite at the Ravinia Festival on June 29, 1941, with Frederick Stock conducting; the complete suite was first performed at Ravinia on August 5 , 1948, with Pierre Monteux conducting, and most recently on August 28, 2000, with Vladimir Feltsman conducting. When the young Mendelssohn played the first movement of Bach’s Third Orchestral Suite on the piano for Goethe, the poet said he could see “a p rocession of elegantly dressed people proceeding down a great staircase.” Bach’s music was nearly forgotten in 1830, and Goethe, never having heard this suite before, can be forgiven for wanting to attach a visual image to such stately and sweeping music. Today it’s hard to imagine a time when Bach’s name meant little to music lovers and when these four orchestral suites weren’t considered landmarks. -

PROGRAM NOTES Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 1 in C

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Johann Sebastian Bach Born March 21, 1685, Eisenach, Thuringia, Germany. Died July 28, 1750, Leipzig, Germany. Orchestral Suite No. 1 in C Major, BWV 1066 The dating of Bach’s four orche stral suites is uncertain. The first and fourth are the earliest, both composed around 1725. Suite no. 1 calls for two oboes and bassoon, with strings and continuo . Performance time is approximately twenty -one minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s fir st subscription concert performances of Bach’s First Orchestral Suite were given at Orchestra Hall on February 22 and 23, 1951, with Rafael Kubelík conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on May 15, 16, and 17, 2003, with D aniel Barenboim conducting. Today it’s hard to imagine a time when Bach’s name meant little to music lovers, and when his four orchestral suites weren’t considered landmarks. But in the years immediately following Bach’s death in 1750, public knowledge o f his music was nil, even though other, more cosmopolitan composers, such as Handel, who died only nine years later, remained popular. It’s Mendelssohn who gets the credit for the rediscovery of Bach’s music, launched in 1829 by his revival of the Saint Ma tthew Passion in Berlin. A great deal of Bach’s music survives, but incredibly, there’s much more that didn’t. Christoph Wolff, today’s finest Bach biographer, speculates that over two hundred compositions from the Weimar years are lost, and that just 15 to 20 percent of Bach’s output from his subsequent time in Cöthen has survived. -

Dance Topics I: Music and Dance in the Ancien Régime

Dance Topics I: Music and Dance in the Ancien Régime Lawrence M. Zbikowski University of Chicago, Department of Music [this is a draft of a contribution to the Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory, ed. Danuta Mirka, which is presently under review] In 1777, Johann Philipp Kirnberger paused in the production of his monumental Die Kunst des reinen Satzes in der Musik to publish a Recueil d’airs de danse caractéristiques. On the one hand, the relationship between the modest dances of Kirnberger’s collection and the careful, methodical setting out of the art of strict musical composition is not immediately evident, as the two seem to belong to rather different intellectual registers. On the other hand, there is evidence that, for Kirnberger, the relationship between the two works was quite intimate. As the preface to the Recueil makes clear, the twenty-odd dances gathered by Kirnberger were meant to set out for the young musician the characteristic features of different dance types, as he believed familiarity with these was essential to understanding musical organization. In order to acquire the necessary qualities for a good performance, the musician can do nothing better than diligently play all sorts of characteristic dances. Each dance has its own rhythm, its passages of the same length, its accents on particular places in each measure; one thus easily recognizes them, and becomes accustomed, through playing them often, to attribute to each its particular rhythm, and to mark its patterns of measures and accents, so that one recognizes easily, in a long piece of music, the rhythms, sections and accents, so different from each other and so mixed up together. -

Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano Amy Jun Ming Chin Minnesota State University - Mankato

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects 2012 Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano Amy Jun Ming Chin Minnesota State University - Mankato Follow this and additional works at: http://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Chin, Amy Jun Ming, "Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano" (2012). Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects. Paper 195. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano By Amy J. Chin Program Notes Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music In Piano Performance Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota April 2012 Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano Amy Jun Ming Chin This program notes has been examined and approved by the following members of the program notes committee. Dr. David Viscoli, Advisor Dr.Linda B. Duckett Dr. Karen Boubel Preface The purpose of this paper is to offer a biographical background of the composers, and historical and theoretical analysis of the works performed in my Master’s recital. This will assist the listener to better understand the music performed. Acknowledgements I would like to thank members of my examining committee, Dr. -

Lunchtime Concert Slava Grigoryan Guitar Sharon Grigoryan Cello

Sharon Grigoryan has been the cellist with the Australian String Quartet since 2013, and has been invited to be Guest Principal Cellist with the Melbourne, Adelaide and Tasmanian Symphony Orchestras. She is the current Artistic Director of the Barossa, Baroque and Beyond music festival, which recently completed its fifth year. In 2019 Sharon curated a chamber music series, Live at the Quartet Bar, for the Adelaide Festival Centre, and made her debut as a radio presenter on ABC Classic. Regarded as a wizard of the guitar, Slava Grigoryan has forged a prolific reputation as a classical guitar virtuoso. Born in Kazakhstan, he immigrated with his family to Australia in 1981 and began studying the guitar with his violinist father Edward at the age of 6. By the time he was 17 he was signed to the Sony Classical Label. His relationship with Sony Classical, ABC Classic in Australia, ECM in Germany and his own label Which Way Music has led to the release of over 30 solo and collaborative albums – four of which have won ARIA Awards – spanning a vast range of musical genres. Since 2009 Slava has been the Artistic Director of the Adelaide Guitar Festival. Lunchtime Concert Slava Grigoryan guitar Sharon Grigoryan cello Friday 25 September, 1:10pm Throughout, Bach’s contrapuntal genius shows in his ability to project multiple PROGRAM voices and implied harmonies with what is often considered a single-line Jobiniana No. 4 Sergio Assad instrument. Maurice Ravel’s Pièce en forme de Habanera was actually originally written as a Sarabande from Cello Suite No.