An Examination of Stylistic Mixture in Four Bassoon Sonatas, 1720–1760

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6 VIOLIN SONATAS Federico Del Sordo FRANKFURT 1715 Harpsichord

Valerio Losito Baroque violin 6 VIOLIN SONATAS Federico Del Sordo FRANKFURT 1715 harpsichord Telemann GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN (1681–1767) Six Sonatas for Solo Violin, 1715 6 Sonatas ‘Frankfurt 1715’ for solo violin and harpsichord “My Lord, I am not without fear in dedicating these sonatas to Your Highness. It is, Sire, that without mentioning the vivacity of your sublime mind, you also have such certain taste in this fine art, which is the only one with the advantage of begin eternal, Sonata No.1 in G minor TWV41:g1 Sonata No.4 in G TWV41:G1 though it is very hard to create in a work worthy of your approbation. My Lord, I 1. Adagio 1’43 13. Largo 1’12 flatter myself that with this gift of the first pieces that I have had published you will 2. Allegro 2‘45 14. Allegro 2’18 find acceptable my intention of recognizing in some way the favour with which you 3. Adagio 1’08 15. Adagio 2’48 have hitherto honoured me. If, my Lord, my work is thus fortunate enough to meet 4. Vivace 3’03 16. Allegro 2’30 with your pleasure, then I am assured of the support of all connoisseurs, because no one can hope to achieve such understanding as yours. The beauty of the Concertos Sonata No.2 in D TWV41:D1 Sonata No.5 in A minor TWV41:a1 that you yourself have written at such a young age is admired by all those who have 5. Allemanda, Largo 3’52 17. Allemanda, Largo 2’37 seen them, and this is a guarantee for me in my aim. -

Bassoon Solo List

If you do not see your solo: Solo level request form New Jersey Youth Symphony Solo Audition Requirements 2019-2020 Bassoon Solo List LEVEL ONE 07501 Bach,J.S. Polonaise 07502 Bach,J.S. Bourree I & II (Both) 07503 Bach,J.S./Krane,C. Bach for Bassoon (Any I) 07504 Baines,F. Introduction & Hornpipe 07505 Bakaleinikov,V. Three Pieces (Nos.1&3) 07506 Beethoven,L. Sonatina Anh.5, No. I 07507 Boyce,W./Vedeski,A. Gavotte Symphony No.4 07508 Cacavas,J. Poem 07509 Couperin,F. La Bouffonne 07510 Debussy,C./Paine,H. Sarabande 07511 Duport,J. Romance 07512 Gounod,C./Walters,H. March of a Marionette 07513 Handel Bouree from Fllute Sonata HWY 363b 07514 Haydn,J. Minuet 07515 Haydn,J. Minuet 07516 Lamb,J.(ed.) Classic Festival Solos, Vol.1 07517 Lamb,J.(ed.) Classic Festival Solos, Vol.2 (Either) 07518 Lully,J./Post,S. Gavotte in Rondeau 07519 Marcello,B./Merriman,L. Largo & Allegro 07520 Marcello,B./Merriman,L. Adagio & Allegro 07521 Massenet,J./Johnson,C. Elegy 07522 Paine,H. Scherzo 07523 Pearson,B./ Elledge,M. Standard of Excellence Festival Solos, Bk.2 (Any I) 07524 Pergolesi,G./Barnes,C. Canzona 07525 Pergolesi,G./Elkan,H. Se Tu M'ami. 07526 Phillips,H.(ed.) Eight Bel Canto Songs (Any 2) 07527 Poldini,E./Simpson,W. Poupec Valsante 07528 Ponce,M./Simpson,W. Estrellita 07529 Purcell,H./Dishinger,R. Gavotte and Hornpipe 07530 Purcell,H.Nedeski,A. Gavotte Harpsichord Suite No.5 07531 Rathaus,K. Polichinelle 07532 Ravel,M./Dishinger,R. Pavane pour une infante defunte 07533 Rose,M. -

Student Recital

Student Recital Room 106 Schaefer Fine Arts Center Gustavus Adolphus College Saturday, July 21st, 2007 9:00:AM Program » Quintet Op. 77 in G Major Antonin Dvorak (1841-1904) Angela Xie, violin Julia Johnson, violin Elizabeth Johnson, violin Bjorn Hovland, cello Matt Minteer, bass Bourrie 1 from Suite 43 inC Major Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) John Sholund, bass guitar . Preguntale a Las Estrellas Latin American Folk Song Arr, Edward Kilenyi Christine Hoffman, mezzo-soprano Galina Zisk, piano Intorno all’idol mio Marco Antonio Cesti z (1623-1669) Christine Mennicke, soprano Galina Zisk, piano a a i a We ask that all members of the audience refrain from photographing or recording the performance. Please be sure that a all cell phones, beepers, alarms, and similar devices are turned off. cm A high-fidelity recording of this performance may be ordered. A @ brochure will be available following the performance. = You are invited to attend the next events of a The 2007 Lutheran Summer Music Festival: = Student Recitals a Christ Chapel & Room 214, and Room 106 Schaefer Fine Arts Center = Gustavus Adolphus College = Saturday, July 21st, 2007 10:30 AM, 12:00 PM, and 2:30 PM | al Jazz Ensemble Concert Bjérling Recital Hall «a Schaefer Fine Arts Center e Gustavus Adolphus College Saturday, July 21st, 2007 ea 1:00 PM e Festival Orchestra Concert e Christ Chapel a Gustavus Adolphus College Saturday, July 21st, 2007 e 7:00 PM = e This concert is the thirty-eighth event of = Lutheran Summer Music Festival 2007 = = «a «= ee se «= LUTHERAN. UMIME Ro ~~__ACADEMY & FESTIVAL Collegium Musicum S. -

2002-2003 the Lynn University Philharmonia Orchestra

THE CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC Presents "THE LYNN UNIVERSITY PHILHARMONIA ORCHESTRA'' DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF RUTH NELSON KRAFT Saturday, November 9, 2002 7:30 p.rn. The Green Center Introduction - Graciela Helguero, Assistant Professor, Spanish Overture in G ("Burlesque de Quichotte") ............. Georg Philip Telemann Overture Awakening on the Windmills Sighs of Love for Princess Aline Sancho Panza Swindled Don Quixote (Trombone Concerto #2) .................................. Jan Sandstrom Introduction - A Windmill Ride To Walk Where the Bold Man Makes a Halt To Row Against a Rushing Stream To Believe in an Insane Dream To Smile Despite Unbearable Pain And Yet When You Succumb,Try to Reach this Star in the Sky Mark Hetzler, trombone INTERMISSION Don Quixote............................................................................ Richard Strauss Introduction Don Quixote - Sancho Panza Var. I: Departure; the Adventure with the Windmills Var. II: The Battle with the Sheep Var. ill: Sancho's Wishes, Peculiarities of Speech and Maxims Var. IV: The Adventure with the Procession of Penitents Var. V: Don Quixote's Vigil During the Summer Night Var. VI: Dulcinea Var. VII: Don Quixote's Ride Through the Air Var. Vill: The Trip on the Enchanted Boat Var. IX: The Attack on the Mendicant Friars Var. X: The Duel and Return Home Epilogue: Don Quixote's Mind Clears. Death of Don Quixote Johanne Perron, cello rthur eisberg, conductor Mr. Weisberg is considered to be among the world's leading bassoonists. He has played with the Houston, Baltimore, and Cleveland Orchestras, as well as with the Symphony of the Air and the New York Woodwind Quintet. As a music director, Mr. Weisberg has worked with the New Chamber Orchestra of Westchester, Orchestra de Camera (of Long Island, New York), Contemporary Chamber Ensemble, Orchestra of the 20th Century, Stony Brook Symphony, Iceland Symphony, and Ensemble 21. -

Jan Dismas Zelenka's Missae Ultimae

Jan Dismas Zelenka's Missa Dei Patris (1740): The Use of stile misto in Missa Dei Patris (ZWV 19) Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Cho, Hyunjin Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 20:42:28 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195489 JAN DISMAS ZELENKA‟S MISSA DEI PATRIS (1740): THE USE OF STILE MISTO IN MISSA DEI PATRIS (ZWV 19) by HyunJin Cho ______________________ Copyright © HyunJin Cho 2010 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2010 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by HyunJin Cho entitled Jan Dismas Zelenka‟s Missa Dei Patris (1740): The Use of stile misto in Missa Dei Patris (ZWV 19) and recommend that it be accepted as the fulfilling requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts ___________________________________________________ Date: 07/16/2010 Bruce Chamberlain ___________________________________________________ Date: 07/16/2010 Elizabeth Schauer ___________________________________________________ Date: 07/16/2010 Robert Bayless Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate‟s submission of the final copy of the document to the Graduate College. -

Apollo's Fire

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Saturday, November 9, 2013, 8pm Johann David Heinichen (1683–1789) Selections from Concerto Grosso in G major, First Congregational Church SeiH 213 Entrée — Loure Menuet & L’A ir à L’Ita lien Apollo’s Fire The Cleveland Baroque Orchestra Heinichen Concerto Grosso in C major, SeiH 211 Jeannette Sorrell, Music Director Allegro — Pastorell — Adagio — Allegro assai Francis Colpron, recorder Kathie Stewart, traverso PROGRAM Debra Nagy, oboe Olivier Brault, violin Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) “Brandenburg” Concerto No. 3 in G major, BWV 1048 Bach “Brandenburg” Concerto No. 4 in G major, BWV 1049 Allegro — Adagio — Allegro Allegro — Andante — Presto Olivier Brault, violin Bach “Brandenburg” Concerto No. 5 in D major, Francis Colpron & Kathie Stewart, recorders BWV 1050 Allegro Affettuoso The Apollo’s Fire national tour of the “Brandenburg” Concertos is made possible by Allegro a generous grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Jeannette Sorrell, harpsichord Apollo’s Fire’s CDs, including the complete “Brandenburg” Concertos, are for sale in the lobby. Olivier Brault, violin The artists will be on hand to sign CDs following the concert. Kathie Stewart, traverso INTERMISSION Cal Performances’ 2013–2014 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 16 CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES 17 PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES a mountaintop experience: extraordinary power to move, delight, and cap- Concerto No. 5 requires from the harpsi- performing concertos for the virtuoso bands of europe tivate audiences for 250 years. But what is it that chordist a level of speed in the scalar passages gives them that power—that greatness that we that far exceeds anything else in the repertoire. -

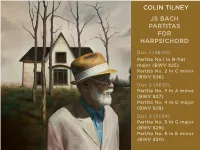

Js Bach Partitas for Harpsichord Colin Tilney

COLIN TILNEY JS BACH PARTITAS FOR HARPSICHORD Disc 1 (48:34) Partita No.1 in B-flat major (BWV 825) Partita No. 2 in C minor (BWV 826) Disc 2 (56:51) Partita No. 3 in A minor (BWV 827) Partita No. 4 in D major (BWV 828) Disc 3 (51:54) Partita No. 5 in G major (BWV 829) Partita No. 6 in E minor (BWV 830) COLIN TILNEY js bach partitas for harpsichord Disc 1 (48:34) Disc 2 (56:51) Disc 3 (51:54) Partita No.1 in B-flat major (BWV 825) Partita No. 3 in A minor (BWV 827) Partita No. 5 in G major (BWV 829) 1. 1. Præludium 2:24 Fantasia 3:17 1. Præambulum 3:14 2. 2. Allemande 4:59 Allemande 3:19 2. Allemande 2:55 3. 3. Corrente 4:09 Corrente 2:12 3. Corrente 2:49 4. Sarabande 6:16 4. Sarabande 3:54 4. Sarabande 4:11 5. Menuets 1 & 2 3:30 5. Burlesca 2:59 5. Tempo di Minuetta 2:30 6. Gigue 3:48 6. Scherzo 1:50 6. Passepied 2:24 7. Gigue 5:34 7. Gigue 3:24 Partita No. 2 in C minor (BWV 826) Partita No. 4 in D major (BWV 828) 7. Sinfonia 5:50 Partita No. 6 in E minor (BWV 830) 8. Ouverture 7:57 8. Allemande 5:32 8. Toccata 8:24 9. Allemande 6:12 9. Courante 3:34 9. Allemanda 4:33 10. Courante 5:16 10. Sarabande 3:34 10. Corrente 3:24 11. -

Grieg & Musical Life in England

Grieg & Musical Life in England LIONEL CARLEY There were, I would prop ose, four cornerstones in Grieg's relationship with English musicallife. The first had been laid long before his work had become familiar to English audiences, and the last was only set in place shortly before his death. My cornerstones are a metaphor for four very diverse and, you might well say, ve ry un-English people: a Bohemian viol inist, a Russian violinist, a composer of German parentage, and an Australian pianist. Were we to take a snapshot of May 1906, when Grieg was last in England, we would find Wilma Neruda, Adolf Brodsky and Percy Grainger all established as significant figures in English musicallife. Frederick Delius, on the other hand, the only one of thi s foursome who had actually been born in England, had long since left the country. These, then, were the four major musical personalities, each having his or her individual and intimate connexion with England, with whom Grieg established lasting friendships. There were, of course, others who com prised - if I may continue and then finally lay to rest my architectural metaphor - major building blocks in the Grieg/England edifice. But this secondary group, people like Francesco Berger, George Augener, Stop ford Augustus Brooke, for all their undoubted human charms, were firs t and foremost representatives of British institutions which in their own turn played an important role in Grieg's life: the musical establishment, publishing, and, perhaps unexpectedly religion. Francesco Berger (1834-1933) was Secretary of the Philharmonic Soci ety between 1884 and 1911, and it was the Philharmonic that had first prevailed upon the mature Grieg to come to London - in May 1888 - and to perform some of his own works in the capital. -

'Dream Job: Next Exit?'

Understanding Bach, 9, 9–24 © Bach Network UK 2014 ‘Dream Job: Next Exit?’: A Comparative Examination of Selected Career Choices by J. S. Bach and J. F. Fasch BARBARA M. REUL Much has been written about J. S. Bach’s climb up the career ladder from church musician and Kapellmeister in Thuringia to securing the prestigious Thomaskantorat in Leipzig.1 Why was the latter position so attractive to Bach and ‘with him the highest-ranking German Kapellmeister of his generation (Telemann and Graupner)’? After all, had their application been successful ‘these directors of famous court orchestras [would have been required to] end their working relationships with professional musicians [take up employment] at a civic school for boys and [wear] “a dusty Cantor frock”’, as Michael Maul noted recently.2 There was another important German-born contemporary of J. S. Bach, who had made the town’s shortlist in July 1722—Johann Friedrich Fasch (1688–1758). Like Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767), civic music director of Hamburg, and Christoph Graupner (1683–1760), Kapellmeister at the court of Hessen-Darmstadt, Fasch eventually withdrew his application, in favour of continuing as the newly- appointed Kapellmeister of Anhalt-Zerbst. In contrast, Bach, who was based in nearby Anhalt-Köthen, had apparently shown no interest in this particular vacancy across the river Elbe. In this article I will assess the two composers’ positions at three points in their professional careers: in 1710, when Fasch left Leipzig and went in search of a career, while Bach settled down in Weimar; in 1722, when the position of Thomaskantor became vacant, and both Fasch and Bach were potential candidates to replace Johann Kuhnau; and in 1730, when they were forced to re-evaluate their respective long-term career choices. -

Beyond the Storm

Pamela J. Marshall Beyond the Storm oboe collection of Poetry-Inspired Solos PREVIEWSpindrift Music Company www.spindrift.com Publishing contemporary classical music and promoting its performance and appreciation collection of Poetry-Inspired Solos Beyond the Storm by Pamela J. Marshall for oboe La Mer by Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) From Poems, 1881 A white mist drifts across the shrouds, A wild moon in this wintry sky Gleams like an angry lion's eye Out of a mane of tawny clouds. The muffled steersman at the wheel Is but a shadow in the gloom;-- And in the throbbing engine-room Leap the long rods of polished steel. The shattered storm has left its trace Upon this huge and heaving dome, For the thin threads of yellow foam Float on the waves like ravelled lace. PREVIEWSpindrift Music Company www.spindrift.com aer "La Mer" by Oscar Wilde Beyond the Storm Pamela J. Marshall Andante misterioso, con licenza q = 86 Oboe p p mp pp mp pp 2 p pp mp 4 (like a throbbing engine) 5 (as if two voices, staccato notes extremely clipped) 11 mp pp 15 18 mp pp pp 21 pp mp 26 mp 27 PREVIEW Copyright © 2007 Pamela J. Marshall 28 mf 29 f 33 mf 38 p mp 43 mf 48 mp 51 pp 54 mp p 57 p mf 61 PREVIEWmp 64 p ppp 2 Spindrift Music Company Publishing contemporary classical music and promoting its performance and appreciation 38 Dexter Road Lexington MA 02420-3304 USA 781-862-0884 [email protected] www.spindrift.com Selected Music by Pamela J. -

The Trombone Sonatas of Richard A. Monaco Viii

3T7? No. THE TROMBONE SONATAS OF RICHARD A. MONACO DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By John A. Seidel, B.S., M.M. Denton, Texas December, 19 88 Seidel, John A., The Trombone Sonatas of Richard A. Monaco, A Lecture Recital, Together with Three Recitals of Selected Works by J.S. Bach, Paul Creston, G.F. Handel, Paul Hindemith, Vincent Persichetti, and Others. Doctor of Musical Arts in Trombone Performance, December, 1988, 43 pp., 24 musical examples, bibliography, 28 titles. This lecture-recital investigated the music of Richard A. Monaco, especially the two sonatas for trombone (1958 and 1985). Monaco (1930-1987) was a composer, trombonist and conductor whose instrumental works are largely unpublished and relatively little known. In the lecture, a fairly extensive biographical chapter is followed by an examination of some of Monaco's early influences, particularly those in the music of Hunter Johnson and Robert Palmer, professors of Monaco's at Cornell University. Later style characteristics are discussed in a chapter which examines the Divertimento for Brass Quintet (1977), the Duo for Trumpet and Piano (1982), and the Second Sonata for Trombone and Piano (1985). The two sonatas for trombone are compared stylistically and for their position of importance in the composer's total output. The program included a performance of both sonatas in their entirety. Tape recordings of all performances submitted as dissertation requirements are on deposit in the library of the University of North Texas. -

III CHAPTER III the BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – Flamboyant, Elaborately Ornamented A. Characteristic

III CHAPTER III THE BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – flamboyant, elaborately ornamented a. Characteristics of Baroque Music 1. Unity of Mood – a piece expressed basically one basic mood e.g. rhythmic patterns, melodic patterns 2. Rhythm – rhythmic continuity provides a compelling drive, the beat is more emphasized than before. 3. Dynamics – volume tends to remain constant for a stretch of time. Terraced dynamics – a sudden shift of the dynamics level. (keyboard instruments not capable of cresc/decresc.) 4. Texture – predominantly polyphonic and less frequently homophonic. 5. Chords and the Basso Continuo (Figured Bass) – the progression of chords becomes prominent. Bass Continuo - the standard accompaniment consisting of a keyboard instrument (harpsichord, organ) and a low melodic instrument (violoncello, bassoon). 6. Words and Music – Word-Painting - the musical representation of specific poetic images; E.g. ascending notes for the word heaven. b. The Baroque Orchestra – Composed of chiefly the string section with various other instruments used as needed. Size of approximately 10 – 40 players. c. Baroque Forms – movement – a piece that sounds fairly complete and independent but is part of a larger work. -Binary and Ternary are both dominant. 2. The Concerto Grosso and the Ritornello Form - concerto grosso – a small group of soloists pitted against a larger ensemble (tutti), usually consists of 3 movements: (1) fast, (2) slow, (3) fast. - ritornello form - e.g. tutti, solo, tutti, solo, tutti solo, tutti etc. Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 Title on autograph score: Concerto 2do à 1 Tromba, 1 Flauto, 1 Hautbois, 1 Violino concertati, è 2 Violini, 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo.