The Essercizii Musici: a Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6 VIOLIN SONATAS Federico Del Sordo FRANKFURT 1715 Harpsichord

Valerio Losito Baroque violin 6 VIOLIN SONATAS Federico Del Sordo FRANKFURT 1715 harpsichord Telemann GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN (1681–1767) Six Sonatas for Solo Violin, 1715 6 Sonatas ‘Frankfurt 1715’ for solo violin and harpsichord “My Lord, I am not without fear in dedicating these sonatas to Your Highness. It is, Sire, that without mentioning the vivacity of your sublime mind, you also have such certain taste in this fine art, which is the only one with the advantage of begin eternal, Sonata No.1 in G minor TWV41:g1 Sonata No.4 in G TWV41:G1 though it is very hard to create in a work worthy of your approbation. My Lord, I 1. Adagio 1’43 13. Largo 1’12 flatter myself that with this gift of the first pieces that I have had published you will 2. Allegro 2‘45 14. Allegro 2’18 find acceptable my intention of recognizing in some way the favour with which you 3. Adagio 1’08 15. Adagio 2’48 have hitherto honoured me. If, my Lord, my work is thus fortunate enough to meet 4. Vivace 3’03 16. Allegro 2’30 with your pleasure, then I am assured of the support of all connoisseurs, because no one can hope to achieve such understanding as yours. The beauty of the Concertos Sonata No.2 in D TWV41:D1 Sonata No.5 in A minor TWV41:a1 that you yourself have written at such a young age is admired by all those who have 5. Allemanda, Largo 3’52 17. Allemanda, Largo 2’37 seen them, and this is a guarantee for me in my aim. -

Dynamicsanddissonance: Theimpliedharmonictheoryof

Intégral 30 (2016) pp. 67–80 Dynamics and Dissonance: The Implied Harmonic Theory of J. J. Quantz by Evan Jones Abstract. Chapter 17, Section 6 of Quantz’s Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traver- siere zu spielen (1752) includes a short original composition entitled “Affettuoso di molto.” This piece features an unprecedented variety of dynamic markings, alternat- ing abruptly from loud to soft extremes and utilizing every intermediate gradation. Quantz’s discussion of this example provides an analytic context for the dynamic markings in the score: specific levels of relative amplitude are prescribed for particu- lar classes of harmonic events, depending on their relative dissonance. Quantz’s cat- egories anticipate Kirnberger’s distinction between essential and nonessential dis- sonance and closely coincide with even later conceptions as indicated by the various chords’ spans on the Oettingen–Riemann Tonnetz and on David Temperley’s “line of fifths.” The discovery of a striking degree of agreement between Quantz’s prescrip- tions for performance and more recent theoretical models offers a valuable perspec- tive on eighteenth-century musical intuitions and suggests that today’s intuitions might not be very different. Keywords and phrases: Quantz, Versuch, Affettuoso di molto, thoroughbass, disso- nance, dynamics, Kirnberger, Temperley, line of fifths, Tonnetz. 1. Dynamic Markings in Quantz’s ing. Like similarly conceived publications by C. P. E. Bach, “Affettuoso di molto” Leopold Mozart, and others, however, Quantz’s treatise en- gages -

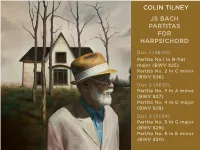

Js Bach Partitas for Harpsichord Colin Tilney

COLIN TILNEY JS BACH PARTITAS FOR HARPSICHORD Disc 1 (48:34) Partita No.1 in B-flat major (BWV 825) Partita No. 2 in C minor (BWV 826) Disc 2 (56:51) Partita No. 3 in A minor (BWV 827) Partita No. 4 in D major (BWV 828) Disc 3 (51:54) Partita No. 5 in G major (BWV 829) Partita No. 6 in E minor (BWV 830) COLIN TILNEY js bach partitas for harpsichord Disc 1 (48:34) Disc 2 (56:51) Disc 3 (51:54) Partita No.1 in B-flat major (BWV 825) Partita No. 3 in A minor (BWV 827) Partita No. 5 in G major (BWV 829) 1. 1. Præludium 2:24 Fantasia 3:17 1. Præambulum 3:14 2. 2. Allemande 4:59 Allemande 3:19 2. Allemande 2:55 3. 3. Corrente 4:09 Corrente 2:12 3. Corrente 2:49 4. Sarabande 6:16 4. Sarabande 3:54 4. Sarabande 4:11 5. Menuets 1 & 2 3:30 5. Burlesca 2:59 5. Tempo di Minuetta 2:30 6. Gigue 3:48 6. Scherzo 1:50 6. Passepied 2:24 7. Gigue 5:34 7. Gigue 3:24 Partita No. 2 in C minor (BWV 826) Partita No. 4 in D major (BWV 828) 7. Sinfonia 5:50 Partita No. 6 in E minor (BWV 830) 8. Ouverture 7:57 8. Allemande 5:32 8. Toccata 8:24 9. Allemande 6:12 9. Courante 3:34 9. Allemanda 4:33 10. Courante 5:16 10. Sarabande 3:34 10. Corrente 3:24 11. -

'Dream Job: Next Exit?'

Understanding Bach, 9, 9–24 © Bach Network UK 2014 ‘Dream Job: Next Exit?’: A Comparative Examination of Selected Career Choices by J. S. Bach and J. F. Fasch BARBARA M. REUL Much has been written about J. S. Bach’s climb up the career ladder from church musician and Kapellmeister in Thuringia to securing the prestigious Thomaskantorat in Leipzig.1 Why was the latter position so attractive to Bach and ‘with him the highest-ranking German Kapellmeister of his generation (Telemann and Graupner)’? After all, had their application been successful ‘these directors of famous court orchestras [would have been required to] end their working relationships with professional musicians [take up employment] at a civic school for boys and [wear] “a dusty Cantor frock”’, as Michael Maul noted recently.2 There was another important German-born contemporary of J. S. Bach, who had made the town’s shortlist in July 1722—Johann Friedrich Fasch (1688–1758). Like Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767), civic music director of Hamburg, and Christoph Graupner (1683–1760), Kapellmeister at the court of Hessen-Darmstadt, Fasch eventually withdrew his application, in favour of continuing as the newly- appointed Kapellmeister of Anhalt-Zerbst. In contrast, Bach, who was based in nearby Anhalt-Köthen, had apparently shown no interest in this particular vacancy across the river Elbe. In this article I will assess the two composers’ positions at three points in their professional careers: in 1710, when Fasch left Leipzig and went in search of a career, while Bach settled down in Weimar; in 1722, when the position of Thomaskantor became vacant, and both Fasch and Bach were potential candidates to replace Johann Kuhnau; and in 1730, when they were forced to re-evaluate their respective long-term career choices. -

T H O M a N E R C H

Thomanerchor LeIPZIG DerThomaner chor Der Thomaner chor ts n te on C F o able T Ta b l e o f c o n T e n T s Greeting from “Thomaskantor” Biller (Cantor of the St Thomas Boys Choir) ......................... 04 The “Thomanerchor Leipzig” St Thomas Boys Choir Now Performing: The Thomanerchor Leipzig ............................................................................. 06 Musical Presence in Historical Places ........................................................................................ 07 The Thomaner: Choir and School, a Tradition of Unity for 800 Years .......................................... 08 The Alumnat – a World of Its Own .............................................................................................. 09 “Keyboard Polisher”, or Responsibility in Detail ........................................................................ 10 “Once a Thomaner, always a Thomaner” ................................................................................... 11 Soli Deo Gloria .......................................................................................................................... 12 Everyday Life in the Choir: Singing Is “Only” a Part ................................................................... 13 A Brief History of the St Thomas Boys Choir ............................................................................... 14 Leisure Time Always on the Move .................................................................................................................. 16 ... By the Way -

JS BACH (1685-1750): Violin and Oboe Concertos

BACH 703 - J. S. BACH (1685-1750) : Violin and Oboe Concertos Johann Sebastian Bach was born on March 21 st , l685, the son of Johann Ambrosius, Court Trumpeter for the Duke of Eisenach and Director of the Musicians of the town of Eisenach in Thuringia. For many years, members of the Bach family throughout Thuringia had held positions such as organists, town instrumentalists, or Cantors, and the family name enjoyed a wide reputation for musical talent. By the year 1703, 18-year-old Johann Sebastian had taken up his first professional position: that of Organist at the small town of Arnstadt. Then, in 1706 he heard that the Organist to the town of Mülhausen had died. He applied for the post and was accepted on very favorable terms. However, a religious controversy arose in Mülhausen between the Orthodox Lutherans, who were lovers of music, and the Pietists, who were strict puritans and distrusted art. So it was that Bach again looked around for more promising possibilities. The Duke of Weimar offered him a post among his Court chamber musicians, and on June 25, 1708, Bach sent in his letter of resignation to the authorities at Mülhausen. The Weimar years were a happy and creative time for Bach…. until in 1717 a feud broke out between the Duke of Weimar at the 'Wilhelmsburg' household and his nephew Ernst August at the 'Rote Schloss’. Added to this, the incumbent Capellmeister died, and Bach was passed over for the post in favor of the late Capellmeister's mediocre son. Bach was bitterly disappointed, for he had lately been doing most of the Capellmeister's work, and had confidently expected to be given the post. -

The Sources of the Christmas Interpolations in J. S. Bach's Magnificat in E-Flat Major (BWV 243A)*

The Sources of the Christmas Interpolations in J. S. Bach's Magnificat in E-flat Major (BWV 243a)* By Robert M. Cammarota Apart from changes in tonality and instrumentation, the two versions of J. S. Bach's Magnificat differ from each other mainly in the presence offour Christmas interpolations in the earlier E-flat major setting (BWV 243a).' These include newly composed settings of the first strophe of Luther's lied "Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her" (1539); the last four verses of "Freut euch und jubiliert," a celebrated lied whose origin is unknown; "Gloria in excelsis Deo" (Luke 2:14); and the last four verses and Alleluia of "Virga Jesse floruit," attributed to Paul Eber (1570).2 The custom of troping the Magnificat at vespers on major feasts, particu larly Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost, was cultivated in German-speaking lands of central and eastern Europe from the 14th through the 17th centu ries; it continued to be observed in Leipzig during the first quarter of the 18th century. The procedure involved the interpolation of hymns and popu lar songs (lieder) appropriate to the feast into a polyphonic or, later, a con certed setting of the Magnificat. The texts of these interpolations were in Latin, German, or macaronic Latin-German. Although the origin oftroping the Magnificat is unknown, the practice has been traced back to the mid-14th century. The earliest examples of Magnifi cat tropes occur in the Seckauer Cantional of 1345.' These include "Magnifi cat Pater ingenitus a quo sunt omnia" and "Magnificat Stella nova radiat. "4 Both are designated for the Feast of the Nativity.' The tropes to the Magnificat were known by different names during the 16th, 17th, and early 18th centuries. -

An Historical and Analytical Study of Renaissance Music for the Recorder and Its Influence on the Later Repertoire Vanessa Woodhill University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1986 An historical and analytical study of Renaissance music for the recorder and its influence on the later repertoire Vanessa Woodhill University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Woodhill, Vanessa, An historical and analytical study of Renaissance music for the recorder and its influence on the later repertoire, Master of Arts thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1986. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2179 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] AN HISTORICAL AND ANALYTICAL STUDY OF RENAISSANCE MUSIC FOR THE RECORDER AND ITS INFLUENCE ON THE LATER REPERTOIRE by VANESSA WOODHILL. B.Sc. L.T.C.L (Teachers). F.T.C.L A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the School of Creative Arts in the University of Wollongong. "u»«viRsmr •*"! This thesis is submitted in accordance with the regulations of the University of Wotlongong in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. I hereby certify that the work embodied in this thesis is the result of original research and has not been submitted for a higher degree at any other University or similar institution. Copyright for the extracts of musical works contained in this thesis subsists with a variety of publishers and individuals. Further copying or publishing of this thesis may require the permission of copyright owners. Signed SUMMARY The material in this thesis approaches Renaissance music in relation to the recorder player in three ways. -

Johann Joachim Quantz

Johann Joachim Quantz Portrait by an unknown 18th-century artist An account of his life taken largely from his autobiography published in 1754–5 Greg Dikmans Johann Joachim Quantz (1697–1773) Quantz was a flute player and composer at royal courts, writer on music and flute maker, and one of the most famous musicians of his day. His autobiography, published in F.W. Marpurg’s Historisch-kritische Beyträge (1754– 5), is the principal source of information on his life. It briefly describes his early years and then focuses on his activities in Dresden (1716–41), his Grand Tour (1724– 27) and his work at the court of Frederick the Great in Berlin and Potsdam (from 1741). Quantz was born in the village Oberscheden in the province of Hannover (northwestern Germany) on 30 January 1697. His father was a blacksmith. At the age of 11, after being orphaned, he began an apprenticeship (1708–13) with his uncle Justus Quantz, a town musician in Merseburg. Quantz writes: I wanted to be nothing but a musician. In August … I went to Merseburg to begin my apprenticeship with the former town-musician, Justus Quantz. … The first instrument which I had to learn was the violin, for which I also seemed to have the greatest liking and ability. Thereon followed the oboe and the trumpet. During my years as an apprentice I worked hardest on these three instruments. Merseburg Matthäus Merian While still an apprentice Quantz also arranged to have keyboard lessons: (1593–1650) Due to my own choosing, I took some lessons at this time on the clavier, which I was not required to learn, from a relative of mine, the organist Kiesewetter. -

The Program E E

W the program E E 24 K june RISING STAR SERIES 4 y a d s Daria Rabotkina, piano e u T 8 PM “FLOW MY TEARES” (1600) John Dowland (1563-1626)/arr. Daria Rabotkina SONATA IN E MAJOR, K. 162 (1756-57) Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757) Andante—Allegro—Andante—Allegro SELECTIONS FROM ORDRE 18ÈME DE CLAVECIN IN F MAJOR (1722) François Couperin (1668-1733) ITALIAN CONCERTO, BWV 971 ( ca . 1735) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) [without tempo designation] Andante Presto :: intermission :: SONATINE (1903-05) Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Modéré Mouvement de menuet Animé SONATA NO. 3 IN A MINOR FOR PIANO, OP. 28 (1917) Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) Allegro tempestoso—Moderato—Allegro tempestoso—Moderato—Più lento—Più animato—Allegro I—Poco più mosso FANTASY SUITE AFTER BIZET’S CARMEN , 1ST MOVEMENT Sergei Rabotkin (b. 1953) This concert is made possible in part through the generosity of Pat Petrou. Ms. Rabotkina is a winner of the Concert Artists Guild International Competition and is represented by Concert Artists Guild. concertartists.org 33RD SEASON | ROCKPORT MUSIC :: 51 “FLOW MY TEARES” John Dowland (b. London, 1563; d. London, February 20, 1626)/arr. Daria Rabotkina Composed 1600 Non otthees program In addition to wide-ranging “traditional” piano repertoire, Daria Rabotkina has acquired a substantial store of piano works borrowed and adapted from far-flung places in the music by world, including her own concert arrangement* of ragtime legend “Luckey” Roberts’s “Pork Sandra Hyslop and Beans.” As the opening offering on this evening’s concert—in contrast to the fantasy on Bizet’s stormy opera Carmen with which she closes—Ms. -

Five Late Baroque Works for String Instruments Transcribed for Clarinet and Piano

Five Late Baroque Works for String Instruments Transcribed for Clarinet and Piano A Performance Edition with Commentary D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of the The Ohio State University By Antoine Terrell Clark, M. M. Music Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2009 Document Committee: Approved By James Pyne, Co-Advisor ______________________ Co-Advisor Lois Rosow, Co-Advisor ______________________ Paul Robinson Co-Advisor Copyright by Antoine Terrell Clark 2009 Abstract Late Baroque works for string instruments are presented in performing editions for clarinet and piano: Giuseppe Tartini, Sonata in G Minor for Violin, and Violoncello or Harpsichord, op.1, no. 10, “Didone abbandonata”; Georg Philipp Telemann, Sonata in G Minor for Violin and Harpsichord, Twv 41:g1, and Sonata in D Major for Solo Viola da Gamba, Twv 40:1; Marin Marais, Les Folies d’ Espagne from Pièces de viole , Book 2; and Johann Sebastian Bach, Violoncello Suite No.1, BWV 1007. Understanding the capabilities of the string instruments is essential for sensitively translating the music to a clarinet idiom. Transcription issues confronted in creating this edition include matters of performance practice, range, notational inconsistencies in the sources, and instrumental idiom. ii Acknowledgements Special thanks is given to the following people for their assistance with my document: my doctoral committee members, Professors James Pyne, whose excellent clarinet instruction and knowledge enhanced my performance and interpretation of these works; Lois Rosow, whose patience, knowledge, and editorial wonders guided me in the creation of this document; and Paul Robinson and Robert Sorton, for helpful conversations about baroque music; Professor Kia-Hui Tan, for providing insight into baroque violin performance practice; David F. -

The Lute's Influence on Seventeenth-Century Harpsichord

Audrey S. Rutt 12 April 2017 A BLEND OF TRADITIONS: THE LUTE’S INFLUENCE ON SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY HARPSICHORD REPERTOIRE The Harpsichord ◦ Mechanically, a hybrid instrument ◦ Like the organ: ◦ chromatic keyboard with one pitch per key ◦ well-suited for polyphony and accompaniment ◦ Like the lute: ◦ plucked string instrument ◦ must account for quick sound decay by forms of arpeggiation ◦ Existent by the fifteenth century ◦ Not widely manufactured until the sixteenth century The Organ’s Influence ◦ The early harpsichord style was not distinct from the organ’s ◦ Pieces not designated specifically for either keyboard instrument ◦ Early works were simply transcriptions of vocal or ensemble pieces ◦ Obras de musica para tecla, arpa, y vihuela (Antonio Cabezón, 1510-1566) ◦ vocal transciptions arranged generally for polyphonic string instruments ◦ The broadness of this collection could include the harp, the Spanish vihuela, and the keyboard ◦ suggests that “the stringed keyboard instruments had not developed enough of a basic style to warrant independent compositions of their own” ◦ Early harpsichord composers were also organists, so idioms of the organ tradition were assumed The Organ Tradition ◦ For many centuries, the primary keyboard instrument ◦ Robertsbridge Codex (1320) is first example of newly-composed repertoire but follows vocal tradition closely ◦ Development of a true organ style ◦ Conrad Paumann (1410-1473), Paul Hofhaimer (1459-1537), Andrea Gabrieli (1533-1585) ◦ Fundamentum organisandi ◦ used florid, rhythmically varying upper