Ancient Maya Landscapes in Northwestern Belize

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Maya: the Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization Arthur Demarest Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521592240 - Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization Arthur Demarest Index More information Index Abaj Takalik (Guatemala) 64, 67, 69, 72, animals 76, 78, 84, 102 association with kings and priests 184, aboriculture 144–145 185 acropoli see epicenters and bird life, rain forests 123–126 agriculture 117–118 and rulers 229 animal husbandry 145 apiculture 145 Classic period 90, 146–147 archaeology effects of the collapse, Petexbatun 254 and chronology 17, 26 operations in relation to the role of elites and cultural evolution 22–23, 26, 27 and rulers 213 history 31 post-Spanish Conquest 290 genesis of scientific archaeology 37–41 Postclassic period, Yucatan 278 multidisciplinary archaeology 41–43 in relation to kingship 206 nineteenth century 34–37 specialization 166 Spanish Conquest 31–33 and trade 150 processual archaeology 23, 26 see also farming practices; gardens; rain settlement pattern archaeology 50, 52 forests architecture 99 Aguateca 230, 251, 252, 259, 261 corbeled vault architecture 90, 94, 95 craft production 164 northern lowlands, Late Classic period destruction 253 235–236 specialist craft production 168 Puuc area, Late Classic period 236 Ajaw complex 16 roof combs 95 ajaws, cult 103 talud-tablero architectural facades alliances, and vassalages 209 (Teotihuacan) 105, 108 Alm´endariz, Ricardo 33 Arroyo de Piedras (western Pet´en)259 alphabet 46, 48 astronomy 201 Alta Vista 79 and astrology 192–193 Altar de Sacrificios (Petexbatun) 38, 49, Atlantis (lost continent) 33, 35 81, 256, -

“Charlie Chaplin” Figures of the Maya Lowlands

RITUAL USE OF THE HUMAN FORM: A CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF THE “CHARLIE CHAPLIN” FIGURES OF THE MAYA LOWLANDS by LISA M. LOMITOLA B.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2012 ©2012 Lisa M. Lomitola ii ABSTRACT Small anthropomorphic figures, most often referred to as “Charlie Chaplins,” appear in ritual deposits throughout the ancient Maya sites of Belize during the late Preclassic and Early Classic Periods and later, throughout the Petén region of Guatemala. Often these figures appear within similar cache assemblages and are carved from “exotic” materials such as shell or jade. This thesis examines the contexts in which these figures appear and considers the wider implications for commonly held ritual practices throughout the Maya lowlands during the Classic Period and the similarities between “Charlie Chaplin” figures and anthropomorphic figures found in ritual contexts outside of the Maya area. iii Dedicated to Corbin and Maya Lomitola iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Drs. Arlen and Diane Chase for the many opportunities they have given me both in the field and within the University of Central Florida. Their encouragement and guidance made this research possible. My experiences at the site of Caracol, Belize have instilled a love for archaeology in me that will last a lifetime. Thank you Dr. Barber for the advice and continual positivity; your passion and joy of archaeology inspires me. In addition, James Crandall and Jorge Garcia, thank you for your feedback, patience, and support; your friendship and experience are invaluable. -

Research Reports from the Programme for Belize Archaeological Project, Volume Six

RESEARCH REPORTS FROM THE PROGRAMME FOR BELIZE ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT, VOLUME SIX Edited by: Marisol Cortes-Rincon Humboldt State University And Fred Valdez, Jr. The University of Texas at Austin Occasional Papers, Number 14 Mesoamerican Archaeological Research Laboratory The University of Texas at Austin 2012 RESEARCH REPORTS FROM THE PROGRAMME FOR BELIZE ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT, VOLUME SIX Edited by: Marisol Cortes-Rincon Humboldt State University And Fred Valdez, Jr. The University of Texas at Austin Formatted by: David M. Hyde Western State Colorado University Contributors Grant R. Aylesworth Stacy Drake Deanna Riddick Michael Brandl Eric J. Heller Rissa M. Trachman Michael L. Brennan Brett A. Houk Debora Trein Nicholas Brokaw David M. Hyde Fred Valdez, Jr. Linda A. Brown Saran E. Jackson Sheila Ward David Chatelain Laura Levi Estella Weiss-Krejci Marisol Cortes-Rincon Brandon S. Lewis Gregory Zaro Robyn L. Dodge Katherine MacDonald Occasional Papers, Number 14 Mesoamerican Archaeological Research Laboratory The University of Texas at Austin 2012 Contents Background and Introduction to the 2011 Season of the Programme for Belize Archaeological Project Fred Valdez, Jr. and Marisol Cortes-Rincon ....................................................... 1 Investigations at Structure 3, La Milpa: The 2011 Field Season Debora Trein ........................................................................................................ 5 Report of the 2011 Excavations at the South Ballcourt of La Milpa, Op A6 David Chatelain ................................................................................................ -

Prehistoric Human-Environment Interactions in the Southern Maya Lowlands: the Holmul Region Case

Prehistoric Human-Environment Interactions in the Southern Maya Lowlands: The Holmul Region Case Final Report to the National Science Foundation 2010 Submitted by: Francisco Estrada-Belli and David Wahl Introduction Dramatic population changes evident in the Lowland Maya archaeological record have led scholars to speculate on the possible role of environmental degradation and climate change. As a result, several paleoecological and geochemical studies have been carried out in the Maya area which indicate that agriculture and urbanization may have caused significant forest clearance and soil erosion (Beach et al., 2006; Binford et al., 1987; Deevey et al., 1979; Dunning et al., 2002; Hansen et al., 2002; Jacob and Hallmark, 1996; Wahl et al., 2007). Studies also indicate that the late Holocene was characterized by centennial to millennial scale climatic variability (Curtis et al., 1996; Hodell et al., 1995; Hodell et al., 2001; Hodell et al., 2005b; Medina-Elizalde et al., 2010). These findings reinforce theories that natural or anthropogenically induced environmental change contributed to large population declines in the southern Maya lowlands at the end of the Preclassic (~A.D. 200) and Classic (~A.D. 900) periods. However, a full picture of the chronology and causes of environmental change during the Maya period has not emerged. Many records are insecurely dated, lacking from key cultural areas, or of low resolution. Dating problems have led to ambiguities regarding the timing of major shifts in proxy data (Brenner et al., 2002; Leyden, 2002; Vaughan et al., 1985). The result is a variety of interpretations on the impact of observed environmental changes from one site to another. -

The PARI Journal Vol. XII, No. 3

ThePARIJournal A quarterly publication of the Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute Volume XII, No. 3, Winter 2012 Excavations of Nakum Structure 15: Discoveryof Royal Burials and In This Issue: Accompanying Offerings JAROSŁAW ŹRAŁKA Excavations of Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University NakumStructure15: WIESŁAW KOSZKUL Discovery of Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University Royal Burials and BERNARD HERMES Accompanying Proyecto Arqueológico Nakum, Guatemala Offerings SIMON MARTIN by University of Pennsylvania Museum Jarosław Źrałka Introduction the Triangulo Project of the Guatemalan Wiesław Koszkul Institute of Anthropology and History Bernard Hermes Two royal burials along with many at- (IDAEH). As a result of this research, the and tendant offerings were recently found epicenter and periphery of the site have Simon Martin in a pyramid located in the Acropolis been studied in detail and many structures complex at the Maya site of Nakum. These excavated and subsequently restored PAGES 1-20 discoveries were made during research (Calderón et al. 2008; Hermes et al. 2005; conducted under the aegis of the Nakum Hermes and Źrałka 2008). In 2006, thanks Archaeological Project, which has been to permission granted from IDAEH, a excavating the site since 2006. Artefacts new archaeological project was started Joel Skidmore discovered in the burials and the pyramid Editor at Nakum (The Nakum Archaeological [email protected] significantly enrich our understanding of Project) directed by Wiesław Koszkul the history of Nakum and throw new light and Jarosław Źrałka from the Jagiellonian Marc Zender on its relationship with neighboring sites. University, Cracow, Poland. Recently our Associate Editor Nakum is one of the most important excavations have focused on investigating [email protected] Maya sites located in the northeastern two untouched pyramids located in the Peten, Guatemala, in the area of the Southern Sector of the site, in the area of The PARI Journal Triangulo Park (a “cultural triangle” com- the so-called Acropolis. -

Archaeological Investigations at Holmul, Petén, Guatemala Preliminary Results of the Third Season, 2002

FAMSI © 2003: Francisco Estrada-Belli Archaeological Investigations at Holmul, Petén, Guatemala Preliminary Results of the Third Season, 2002 With contributions by Britta Watters, John Tomasic (Vanderbilt U.) Katie South (S. Illinois U.), Chris Hewitson (English Heritage), Marc Wolf (T.A.M.S.), Kristen Gardella (U. Penn.), Justin Ebersole, James Doyle, David Bell, Andie Gehlhausen (Vanderbilt U.), Kristen Klein (Florida State U.), Collin Watters (Western Illinois, U.), Claudio Lozano Guerra-Librero (Anphorae), Jena DeJuilio, Shoshuanna Parks (Boston U.), Raul Archila, Luis Salazar, Mynor Silvestre, Mario Penados, Angel Chavez, Enrique Monterroso (USAC, CUDEP). Research Year: 2002 Culture: Maya Chronology: Late Pre-Classic to Classic Location: Petén, Guatemala Sites: Holmul, Cival, Hahakab and La Sufricaya Table of Contents Introduction Methodology Synopsis of the 2002 season results Discovery of Hahakab Other Explorations in the Holmul area Mapping at Holmul Excavations within Holmul site center Group 13 Group III, Court A Group III, Court B South Group 1 Salvage excavations at K’o Investigations at La Sufricaya Summary of excavations in Str. 1 Imaging of the La Sufricaya Murals 1-3 Conservation of Murals Summary of excavations in Stelae 4, 5, 6, 8 Residential buildings at La Sufricaya Investigations at Cival Conclusions and future research directions Acknowledgements List of Figures Sources Cited Appendix A. Ceramics Appendix B. Drawings Appendix C. Epigraphy Introduction The present report summarizes the results of the 2002 field season of the Holmul Archaeological Project at Holmul, Petén and at the sites of Cival, Hahakab and La Sufricaya in its vicinity (Figure 1). This field season was made possible thanks to funding from the National Geographic Society, Vanderbilt University, the Ahau Foundation, FAMSI, Interco, as well as permits extended by IDAEH of Guatemala. -

Contextualizing the Protoclassic and Early Classic Periods at Caracol, Belize

1 SAMPLING AND TIMEFRAMES: CONTEXTUALIZING THE PROTOCLASSIC AND EARLY CLASSIC PERIODS AT CARACOL, BELIZE Arlen F. Chase and Diane Z. Chase The era of transition between the Late Preclassic (300 B.C. – A.D. 250) and the Early Classic (A.D. 250-550) Periods is one which saw great change within ancient Maya society. This change is reflected in the ceramics of this transitional era. Ceramicists have had difficulty isolating distinct ceramic complexes within the transitional era and have instead tended to focus on specific stylistic markers (e.g., mamiform tetrapods) that were thought to be hallmarks for this transition. These stylistic markers became known as the “Protoclassic” and, while easily identified, they were never securely anchored within broader patterns of change. To this day the Protoclassic Period remains enigmatic within Maya archaeology. There are disagreements on whether or not the term should be used in Maya archaeology and, if used, how and to what the term should refer. Much of what has been used to identify the Protoclassic falls within the realm of ceramics and, thus, that data class will be the primary one utilized here. This paper first examines the history of and use of the term Protoclassic in Maya archaeology; it then uses data from Caracol, Belize to assess the relevance of the term both to Maya Studies and to interpretations of ancient Maya society. Introduction reflected in the kinds of samples that are used to A solid chronology of the ancient Maya build chronologies and phases and to model past is key to outlining the development of the trade linkages. -

Descargar Este Artículo En Formato

Breuil-Martínez, Véronique, Ervin Salvador López y Erick M. Ponciano 2003 Grandes Grupos Residenciales (GGR) y patrón de asentamiento en La Joyanca, Noroccidente de Petén. En XVI Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2002 (editado por J.P. Laporte, B. Arroyo, H. Escobedo y H. Mejía), pp.232-247. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala. 22 GRANDES GRUPOS RESIDENCIALES (GGR) Y PATRÓN DE ASENTAMIENTO EN LA JOYANCA Y SU MESETA, NOROCCIDENTE DE PETÉN Véronique Breuil-Martínez Ervin Salvador López Erick M. Ponciano El sitio arqueológico La Joyanca se ubica en el borde de una meseta de dirección sureste- noroeste y de unos 5 km de largo (Figuras 1 y 2). Terrenos aptos al cultivo de la milpa así como productivos “bajos en altos” ocupan dicha meseta que se encuentra flanqueada en todos sus lados por terreno bajo, laguna, sibales y áreas anegadas en la época lluviosa que proveen sin embargo una importante reserva de agua durante la época seca. Tres años de reconocimiento en la región permitieron la ubicación de 5 sitios arqueológicos. Se presenta un estudio comparativo de los grandes grupos residenciales del centro y del sector residencial de La Joyanca y de su región a través de la revisión de sus estructuras, de la tipología de los patios, la distribución espacial de los grupos y su ordenamiento tanto en el sitio de La Joyanca (plano del sitio levantado por García y Álvarez en 1996, completado por Morales en 1999, Michelet en 2001 y Lemonnier en 2000, 2001 y 2002), como en su región (mapas y planos levantados por López y Leal en 1999, 2000, 2001y 2002). -

Research Reports from the Programme for Belize Archaeological Project, Volume Two

RESEARCH REPORTS FROM THE PROGRAMME FOR BELIZE ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT, VOLUME TWO Edited by: Fred Valdez, Jr. The University of Texas at Austin Contributors Kirsten Atwood James E. Barrera Angeliki Kalamara Cavazos Robyn Dodge David J. Goldstein Robin Goldstein Liwy Grazioso Sierra Jon B. Hageman Brett A. Houk David M. Hyde Erol Kavountzis Brandon S. Lewis Maria Martinez Antonio Padilla Deanna M. Riddick George Rodriguez Dara Shifrer Lauri McInnis Martin Rissa M. Trachman Debora Trein Fred Valdez, Jr. Jason M. Whitaker Oliver Wigmore Kimberly T. Wren Occasional Papers, Number 9 Mesoamerican Archaeological Research Laboratory The University of Texas at Austin 2008 Contents Situating Research: An introduction to the PfBAP Research Reports (Vol. 2) Fred Valdez, Jr......................................................................................................1 Excavations of Plaza A, Structure 4, at the Site of La Milpa, Belize: A Report of the 2007 Field Season Rissa Trachman...................................................................................................11 Archaeological Investigations at La Milpa, Structures 3 and 93: The 2007 Field Season Liwy Grazioso Sierra...........................................................................................19 Excavations at La Milpa, Belize, Los Pisos Courtyard, Operation A2: Report of the 2007 Season Maria Martinez....................................................................................................29 The 2007 Season of the La Milpa Core Project: An Introduction -

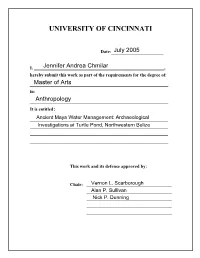

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Ancient Maya Water Management: Archaeological Investigations at Turtle Pond, Northwestern Belize A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the department of Anthropology of the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences July 2005 by Jennifer A. Chmilar B.Sc., University of Calgary, 2002 Committee: Vernon L. Scarborough, Chair Alan P. Sullivan, III Nicholas Dunning ABSTRACT Water is a critical resource for human survival. The ancient Maya, inhabiting an environment with a karstic landscape, semi-tropical climate, and a three month dry season, modified the landscape to create water catchments, drainages, and reservoirs within and surrounding settlement. Water management techniques have been demonstrated in the Maya Lowlands extending back into the Preclassic, approximately 600 BC, at sites such as El Mirador and Nakbe. Into the Classic period, 250 AD – 900 AD, water management features have taken a different form than in the Preclassic; as seen at Tikal and La Milpa. In this thesis, Turtle Pond, a reservoir located on the periphery of the core of La Milpa, is evaluated for modifications to it by the ancient Maya. Turtle Pond was a natural depression that accumulated water for at least part of the year. The ancient Maya then modified it to enhance its water holding potential. -

Ecology and Ritual: Water Management and the Maya Author(S): Vernon L

Society for American Archaeology Ecology and Ritual: Water Management and the Maya Author(s): Vernon L. Scarborough Source: Latin American Antiquity, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Jun., 1998), pp. 135-159 Published by: Society for American Archaeology Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/971991 . Accessed: 10/05/2011 21:13 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sam. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society for American Archaeology is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Latin American Antiquity. http://www.jstor.org ECOLOGYAND RITUAL:WATER MANAGEMENT AND THE MAYA VernonL. -

Extent, Energetics, and Productivity in Wetland Agricultural Systems, Northern Belize

ON THE BACK OF THE CROCODILE: EXTENT, ENERGETICS, AND PRODUCTIVITY IN WETLAND AGRICULTURAL SYSTEMS, NORTHERN BELIZE by: SHANE MATTHEW MONTGOMERY B.A. University of New Mexico, 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2016 © 2016 Shane M. Montgomery ii ABSTRACT Ancient populations across the globe successfully employed wetland agricultural techniques in a variety of environmentally and climatically diverse landscapes throughout prehistory. Within the Maya Lowlands, these agricultural features figure prominently in the region comprised of northern Belize and southern Quintana Roo, an area supporting low-outflow rivers, large lagoons, and numerous bajo features. Along the banks of the Hondo and New Rivers, the Maya effectively utilized wetland agricultural practices from the Middle Preclassic to the Terminal Classic Periods (1000 B.C.—A.D. 950). A number of past archaeological projects have thoroughly examined the construction and impact of these swampland features. After four decades of study, a more precise picture has formed in relation to the roles that these ditched field systems played in the regional development of the area. However, a detailed record of the full spatial extent, combined construction costs, and potential agricultural productivity has not been attempted on a larger scale. This thesis will highlight these avenues of interest through data obtained from high- and medium-resolution satellite imagery and manipulated through geographic information systems (GIS) technology. The research explores environmental factors and topographic elements dictating the distribution of such entities, the energetic involvement required to construct and maintain the systems, and the efficiency of wetland techniques as compared to traditional milpa agriculture.