Origins of the Maya Forest Garden: Maya Resource Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Reports from the Programme for Belize Archaeological Project, Volume Six

RESEARCH REPORTS FROM THE PROGRAMME FOR BELIZE ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT, VOLUME SIX Edited by: Marisol Cortes-Rincon Humboldt State University And Fred Valdez, Jr. The University of Texas at Austin Occasional Papers, Number 14 Mesoamerican Archaeological Research Laboratory The University of Texas at Austin 2012 RESEARCH REPORTS FROM THE PROGRAMME FOR BELIZE ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT, VOLUME SIX Edited by: Marisol Cortes-Rincon Humboldt State University And Fred Valdez, Jr. The University of Texas at Austin Formatted by: David M. Hyde Western State Colorado University Contributors Grant R. Aylesworth Stacy Drake Deanna Riddick Michael Brandl Eric J. Heller Rissa M. Trachman Michael L. Brennan Brett A. Houk Debora Trein Nicholas Brokaw David M. Hyde Fred Valdez, Jr. Linda A. Brown Saran E. Jackson Sheila Ward David Chatelain Laura Levi Estella Weiss-Krejci Marisol Cortes-Rincon Brandon S. Lewis Gregory Zaro Robyn L. Dodge Katherine MacDonald Occasional Papers, Number 14 Mesoamerican Archaeological Research Laboratory The University of Texas at Austin 2012 Contents Background and Introduction to the 2011 Season of the Programme for Belize Archaeological Project Fred Valdez, Jr. and Marisol Cortes-Rincon ....................................................... 1 Investigations at Structure 3, La Milpa: The 2011 Field Season Debora Trein ........................................................................................................ 5 Report of the 2011 Excavations at the South Ballcourt of La Milpa, Op A6 David Chatelain ................................................................................................ -

People of Maize”: Maize Protein Composition and Farmer Practices in the Q’Eqchi’ Maya Milpa

Nourishing the “People of Maize”: Maize Protein Composition and Farmer Practices in the Q’eqchi’ Maya Milpa An honors thesis for the Department of Environmental Studies. Anne Elise Stratton Tufts University, 2015. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 CHAPTER 1 The Q’eqchi’ Milpa in Context Introducing the Milpa The Maize People and the Milpa Forced Migration and Agroecological Adaptation “Grabbed” Land and the Milpa in Transition Milpa in Modernity 23 CHAPTER 2 Linking Biodiversity, Nutrition, and Resilience in the Multispecies Milpa Multispecies Milpa Milpa: Origins and Ideals Today’s Milpa The Milpa as a System 39 CHAPTER 3 Farmer Practices and Maize Nutritional Traits in Sarstún Abstract Introduction Materials and Methods Results Discussion Figures 62 CHAPTER 4 Future Directions 64 LITERATURE CITED ii CHAPTER 1: THE Q’EQCHI MAYA MILPA IN CONTEXT INTRODUCING THE MILPA Nestled along the mangrove-bound border between Belize and Guatemala, in the region called Sarstún, are the clusters of palm-thatch or tin-roofed wooden huts where Q’eqchi’ Maya (henceforth Q’eqchi’) farmers spend their lives. Q’eqchi’ communities can consist of as few as a dozen and as many as 150 families, with an average family size of nine (Grandia 2012: 208). What the casual onlooker may not observe in visiting a village are the communal milpas, or “cornfields,” which physically surround and culturally underlie Q’eqchi’ societies (Grandia 2012: 191). The Q’eqchi’ have traditionally raised maize using swidden (slash-and-burn) techniques, in which they fell a field-sized area of forest, burn the organic matter to release a nutrient pulse into the soil, and then raise their crops on the freshly-cleared land. -

Chec List What Survived from the PLANAFLORO Project

Check List 10(1): 33–45, 2014 © 2014 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution What survived from the PLANAFLORO Project: PECIES S Angiosperms of Rondônia State, Brazil OF 1* 2 ISTS L Samuel1 UniCarleialversity of Konstanz, and Narcísio Department C.of Biology, Bigio M842, PLZ 78457, Konstanz, Germany. [email protected] 2 Universidade Federal de Rondônia, Campus José Ribeiro Filho, BR 364, Km 9.5, CEP 76801-059. Porto Velho, RO, Brasil. * Corresponding author. E-mail: Abstract: The Rondônia Natural Resources Management Project (PLANAFLORO) was a strategic program developed in partnership between the Brazilian Government and The World Bank in 1992, with the purpose of stimulating the sustainable development and protection of the Amazon in the state of Rondônia. More than a decade after the PLANAFORO program concluded, the aim of the present work is to recover and share the information from the long-abandoned plant collections made during the project’s ecological-economic zoning phase. Most of the material analyzed was sterile, but the fertile voucher specimens recovered are listed here. The material examined represents 378 species in 234 genera and 76 families of angiosperms. Some 8 genera, 68 species, 3 subspecies and 1 variety are new records for Rondônia State. It is our intention that this information will stimulate future studies and contribute to a better understanding and more effective conservation of the plant diversity in the southwestern Amazon of Brazil. Introduction The PLANAFLORO Project funded botanical expeditions In early 1990, Brazilian Amazon was facing remarkably in different areas of the state to inventory arboreal plants high rates of forest conversion (Laurance et al. -

The Identity of the African Firebush (Hamelia) in the Ornamental Nursery Trade

HORTSCIENCE 39(6):1224–1226. 2004. and may be extinct. Hamelia versicolor occurs in southern Mexico and partially overlaps with the Mexican populations of H. patens. The The Identity of the African Firebush latter is the most common of all the species and is subdivided into two varieties: H. patens (Hamelia) in the Ornamental Nursery var. patens and H. patens var. glabra Oersted. The widespread H. patens var. patens is found Trade from Florida, the West Indies, and Mexico to Brazil and Argentina. Typically H. patens var. Thomas S. Elias and Margaret R. Pooler patens has red to red-orange fl owers, large U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. National ovate leaves that are moderately to densely Arboretum, 3501 New York Avenue, Washington, D.C. 20002-1958 pubescent, with large variation in leaf size, degree of pubescence, and fl ower and fruit size Additional index words. amplifi ed fragment length polymorphism, AFLP, Rubiaceae, scarlet (Fig. 1, middle). Hamelia patens var. glabra bush, taxonomy, tropical shrub is found in southern Mexico and disjunctly in northern South America, and has smaller, nar- Abstract. The neotropical shrub Hamelia patens Jacq. has been cultivated as an ornamen- rowly ovate pubescent leaves, a more compact tal in the United States, Great Britain, and South Africa for many years, although only in habit, and yellow to yellow-orange fl owers limited numbers and as a minor element in the trade. Recently, other taxa of Hamelia have (Fig. 1, bottom). been grown and evaluated as new fl owering shrubs. The relatively recent introduction of a Specimens of H. -

Prehistoric Human-Environment Interactions in the Southern Maya Lowlands: the Holmul Region Case

Prehistoric Human-Environment Interactions in the Southern Maya Lowlands: The Holmul Region Case Final Report to the National Science Foundation 2010 Submitted by: Francisco Estrada-Belli and David Wahl Introduction Dramatic population changes evident in the Lowland Maya archaeological record have led scholars to speculate on the possible role of environmental degradation and climate change. As a result, several paleoecological and geochemical studies have been carried out in the Maya area which indicate that agriculture and urbanization may have caused significant forest clearance and soil erosion (Beach et al., 2006; Binford et al., 1987; Deevey et al., 1979; Dunning et al., 2002; Hansen et al., 2002; Jacob and Hallmark, 1996; Wahl et al., 2007). Studies also indicate that the late Holocene was characterized by centennial to millennial scale climatic variability (Curtis et al., 1996; Hodell et al., 1995; Hodell et al., 2001; Hodell et al., 2005b; Medina-Elizalde et al., 2010). These findings reinforce theories that natural or anthropogenically induced environmental change contributed to large population declines in the southern Maya lowlands at the end of the Preclassic (~A.D. 200) and Classic (~A.D. 900) periods. However, a full picture of the chronology and causes of environmental change during the Maya period has not emerged. Many records are insecurely dated, lacking from key cultural areas, or of low resolution. Dating problems have led to ambiguities regarding the timing of major shifts in proxy data (Brenner et al., 2002; Leyden, 2002; Vaughan et al., 1985). The result is a variety of interpretations on the impact of observed environmental changes from one site to another. -

Native Trees and Plants for Birds and People in the Caribbean Planting for Birds in the Caribbean

Native Trees and Plants for Birds and People in the Caribbean Planting for Birds in the Caribbean If you’re a bird lover yearning for a brighter, busier backyard, native plants are your best bet. The Caribbean’s native trees, shrubs and flowers are great for birds and other wildlife, and they’re also a part of the region’s unique natural heritage. There’s no better way to celebrate the beauty, culture and birds of the Caribbean than helping some native plants get their roots down. The Habitat Around You Habitat restoration sounds like something that is done by governments in national parks, but in reality it can take many forms. Native plants can turn backyards and neighborhood parks into natural habitats that attract and sustain birds and other wildlife. In the Caribbean, land is precious—particularly the coastal areas where so many of us live. Restoring native habitat within our neighborhoods allows us to share the land with native plants and animals. Of course, it doesn’t just benefit the birds. Native landscaping makes neighborhoods more beautiful and keeps us in touch with Caribbean traditions. Why Native Plants? Many plants can help birds and beautify neighborhoods, but native plants really stand out. Our native plants and animals have developed over millions of years to live in harmony: pigeons eat fruits and then disperse seeds, hummingbirds pollinate flowers while sipping nectar. While many plants can benefit birds, native plants almost always do so best due to the partnerships they have developed over the ages. In addition to helping birds, native plants are themselves worthy of celebration. -

Perspective Statement

2015 Expert Meeting—Spatial Discovery Adler—1 PRUDENCE S. ADLER Associate Executive Director Association of Research Libraries Email: [email protected] Prudence S. Adler is the Associate Executive Director of the Association of Research Libraries. Her responsibilities include federal relations with a focus on information policy, intellectual property, public access policies including open access, accessibility for persons with disabilities and issues relating to access to government information. Prior to joining ARL in 1989, Adler was Assistant Project Director, Communications and Information Technologies Program, Congressional Office of Technology Assessment where she worked on studies relating to government information, networking and supercomputer issues, and information technologies and education. Adler has an M.S. in Library Science and M.A. in American History from the Catholic University of America and a B.A. in History from George Washington University. She has participated in several advisory councils including the Depository Library Council, the National Satellite Land Remote Sensing Data Archive Advisory Committee, the Board of Directors of the National Center for Geographic Information and Analysis, the National Research Council's Steering Committee on Geolibraries, the National Research Council Licensing Geographic Data and Services Committee, the National Institutes of Health PubMed Central National Advisory Committee, and the National Academy of Sciences Forum on Open Science. Perspective Statement he growing understanding of the value of open data in support of research, teaching and T learning presents an important opportunity for research institutions and their libraries. Be it funder policies such as the February 2013 OSTP memo on access to federally funded research resources or journal policies requiring the deposit of digital data associated with an article—for purposes of validation and reuse—in a trusted repository, some data require long-term preservation and access. -

Archaeological Investigations at Holmul, Petén, Guatemala Preliminary Results of the Third Season, 2002

FAMSI © 2003: Francisco Estrada-Belli Archaeological Investigations at Holmul, Petén, Guatemala Preliminary Results of the Third Season, 2002 With contributions by Britta Watters, John Tomasic (Vanderbilt U.) Katie South (S. Illinois U.), Chris Hewitson (English Heritage), Marc Wolf (T.A.M.S.), Kristen Gardella (U. Penn.), Justin Ebersole, James Doyle, David Bell, Andie Gehlhausen (Vanderbilt U.), Kristen Klein (Florida State U.), Collin Watters (Western Illinois, U.), Claudio Lozano Guerra-Librero (Anphorae), Jena DeJuilio, Shoshuanna Parks (Boston U.), Raul Archila, Luis Salazar, Mynor Silvestre, Mario Penados, Angel Chavez, Enrique Monterroso (USAC, CUDEP). Research Year: 2002 Culture: Maya Chronology: Late Pre-Classic to Classic Location: Petén, Guatemala Sites: Holmul, Cival, Hahakab and La Sufricaya Table of Contents Introduction Methodology Synopsis of the 2002 season results Discovery of Hahakab Other Explorations in the Holmul area Mapping at Holmul Excavations within Holmul site center Group 13 Group III, Court A Group III, Court B South Group 1 Salvage excavations at K’o Investigations at La Sufricaya Summary of excavations in Str. 1 Imaging of the La Sufricaya Murals 1-3 Conservation of Murals Summary of excavations in Stelae 4, 5, 6, 8 Residential buildings at La Sufricaya Investigations at Cival Conclusions and future research directions Acknowledgements List of Figures Sources Cited Appendix A. Ceramics Appendix B. Drawings Appendix C. Epigraphy Introduction The present report summarizes the results of the 2002 field season of the Holmul Archaeological Project at Holmul, Petén and at the sites of Cival, Hahakab and La Sufricaya in its vicinity (Figure 1). This field season was made possible thanks to funding from the National Geographic Society, Vanderbilt University, the Ahau Foundation, FAMSI, Interco, as well as permits extended by IDAEH of Guatemala. -

Crop and Soil Variability in Traditional and Modern Mayan Maize Cultivation of Yucatan, Mexico

Crop and Soil Variability in Traditional and Modern Mayan Maize Cultivation of Yucatan, Mexico Sophie Graefe Herausgeber der Schriftenreihe: Deutsches Institut für Tropische und Subtropische Landwirtschaft GmbH, Witzenhausen Gesellschaft für Nachhaltige Entwicklung mbH, Witzenhausen Institut für tropische Landwirtschaft e.V., Leipzig Universität Kassel, Fachbereich Landwirtschaft, Internationale Agrarentwicklung und Ökologische Umweltsicherung (FB11), Witzenhausen Verband der Tropenlandwirte Witzenhausen e.V., Witzenhausen Redaktion: Hans Hemann, Witzenhausen Korrektes Zitat Graefe, Sophie, 2003: Crop and Soil Variability in Traditional and Modern Mayan Maize Cultivation of Yucatan, Mexico, Beiheft Nr. 75 zu Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics, kassel university press GmbH Bibliografische Information Der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar Verlag: kassel university press GmbH www.upress.uni-kassel.de ISSN: 0173 - 4091 ISBN: 3-89958-033-8 Umschlaggestaltung: Jochen Roth, Melchior v. Wallenberg, Kassel Druck und Verarbeitung: Unidruckerei der Universität Kassel August 2003 Crop and Soil Variability in Traditional and Modern Mayan Maize Cultivation of Yucatan, Mexico Conducted as part of a DAAD-funded cooperation between the Faculty of Ecological Agricultural Sciences at the University of Kassel (Germany) and the Universidad Autonoma de Yucatan at Merida (Mexico). This research aimed at documenting the present state of a millennia old shifting cultivation system on fragile tropical soils. The maize-bean-squash ‘milpa-system’ of the Yucatan peninsula has undoubtedly been a mode of ecological and economical sustainable land use as long as population pressure was low enough to allow prolonged fallow periods. -

Descargar Este Artículo En Formato

Breuil-Martínez, Véronique, Ervin Salvador López y Erick M. Ponciano 2003 Grandes Grupos Residenciales (GGR) y patrón de asentamiento en La Joyanca, Noroccidente de Petén. En XVI Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2002 (editado por J.P. Laporte, B. Arroyo, H. Escobedo y H. Mejía), pp.232-247. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala. 22 GRANDES GRUPOS RESIDENCIALES (GGR) Y PATRÓN DE ASENTAMIENTO EN LA JOYANCA Y SU MESETA, NOROCCIDENTE DE PETÉN Véronique Breuil-Martínez Ervin Salvador López Erick M. Ponciano El sitio arqueológico La Joyanca se ubica en el borde de una meseta de dirección sureste- noroeste y de unos 5 km de largo (Figuras 1 y 2). Terrenos aptos al cultivo de la milpa así como productivos “bajos en altos” ocupan dicha meseta que se encuentra flanqueada en todos sus lados por terreno bajo, laguna, sibales y áreas anegadas en la época lluviosa que proveen sin embargo una importante reserva de agua durante la época seca. Tres años de reconocimiento en la región permitieron la ubicación de 5 sitios arqueológicos. Se presenta un estudio comparativo de los grandes grupos residenciales del centro y del sector residencial de La Joyanca y de su región a través de la revisión de sus estructuras, de la tipología de los patios, la distribución espacial de los grupos y su ordenamiento tanto en el sitio de La Joyanca (plano del sitio levantado por García y Álvarez en 1996, completado por Morales en 1999, Michelet en 2001 y Lemonnier en 2000, 2001 y 2002), como en su región (mapas y planos levantados por López y Leal en 1999, 2000, 2001y 2002). -

Research Reports from the Programme for Belize Archaeological Project, Volume Two

RESEARCH REPORTS FROM THE PROGRAMME FOR BELIZE ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT, VOLUME TWO Edited by: Fred Valdez, Jr. The University of Texas at Austin Contributors Kirsten Atwood James E. Barrera Angeliki Kalamara Cavazos Robyn Dodge David J. Goldstein Robin Goldstein Liwy Grazioso Sierra Jon B. Hageman Brett A. Houk David M. Hyde Erol Kavountzis Brandon S. Lewis Maria Martinez Antonio Padilla Deanna M. Riddick George Rodriguez Dara Shifrer Lauri McInnis Martin Rissa M. Trachman Debora Trein Fred Valdez, Jr. Jason M. Whitaker Oliver Wigmore Kimberly T. Wren Occasional Papers, Number 9 Mesoamerican Archaeological Research Laboratory The University of Texas at Austin 2008 Contents Situating Research: An introduction to the PfBAP Research Reports (Vol. 2) Fred Valdez, Jr......................................................................................................1 Excavations of Plaza A, Structure 4, at the Site of La Milpa, Belize: A Report of the 2007 Field Season Rissa Trachman...................................................................................................11 Archaeological Investigations at La Milpa, Structures 3 and 93: The 2007 Field Season Liwy Grazioso Sierra...........................................................................................19 Excavations at La Milpa, Belize, Los Pisos Courtyard, Operation A2: Report of the 2007 Season Maria Martinez....................................................................................................29 The 2007 Season of the La Milpa Core Project: An Introduction -

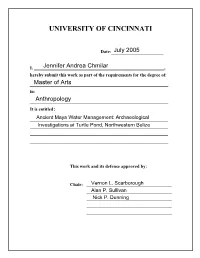

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Ancient Maya Water Management: Archaeological Investigations at Turtle Pond, Northwestern Belize A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the department of Anthropology of the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences July 2005 by Jennifer A. Chmilar B.Sc., University of Calgary, 2002 Committee: Vernon L. Scarborough, Chair Alan P. Sullivan, III Nicholas Dunning ABSTRACT Water is a critical resource for human survival. The ancient Maya, inhabiting an environment with a karstic landscape, semi-tropical climate, and a three month dry season, modified the landscape to create water catchments, drainages, and reservoirs within and surrounding settlement. Water management techniques have been demonstrated in the Maya Lowlands extending back into the Preclassic, approximately 600 BC, at sites such as El Mirador and Nakbe. Into the Classic period, 250 AD – 900 AD, water management features have taken a different form than in the Preclassic; as seen at Tikal and La Milpa. In this thesis, Turtle Pond, a reservoir located on the periphery of the core of La Milpa, is evaluated for modifications to it by the ancient Maya. Turtle Pond was a natural depression that accumulated water for at least part of the year. The ancient Maya then modified it to enhance its water holding potential.